San Diego Symphony Orchestra a Jacobs Masterworks Concert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmina Burana Carl Orff (1895–1982) Composed: 1935–1936 Style: Contemporary Duration: 58 Minutes

Carmina Burana Carl Orff (1895–1982) Composed: 1935–1936 Style: Contemporary Duration: 58 minutes The Latin title of tonight’s major work, translated literally as “Songs of Beuren,” comes from the Abby of Benediktbeuren where a book of poems was discovered in 1803. The Abbey is located about 30 miles south of Munich, where the composer Carl Orff was born, educated, and spent most of his life. The 13th century book contains roughly 200 secular poems that describe medieval times. The poems, written by wandering scholars and clerics known as Goliards, attack and satirize the hypocrisy of the Church while praising the self-indulgent virtues of love, food, and drink. Their language and form often parody liturgical phrases and conventions. Similarly, Orff often uses the styles and conventions of 13th century church music, most notably plainchant, to give an air of seriousness and reverence to the texts that their actual meaning could hardly demand. In addition to plainchant, however, the eclectic musical material relies upon all kinds of historical antecedents— from flamenco rhythms (no. 17, “Stetit puella”) to operatic arias (no. 21, “Intrutina”) to chorale texture (no. 24, “Ave formosissima”). The 24 poems that compose Carmina Burana are divided into three large sections— “Springtime,” “In the Tavern,” and “Court of Love” —plus a prologue and epilogue. The work begins with the chorus “Fortuna imperatrix mundi,” (“Fortune, Empress of the World”), which bemoans humankind’s helplessness in the face of the fickle wheel of fate. “Rising first, then declining, hateful life treats us badly, then with kindness, making sport of our desires.” After a brief morality tale, “Fortune plango vunera,” the “Springtime” section begins. -

Carmina Burana

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie Studijní obor Dirigování orchestru Carl Orff: Carmina Burana Diplomová práce Autor práce: MgA. Marek Prášil Vedoucí práce: prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel Oponent práce: doc. Mgr. Emil Skoták Brno 2017 Bibliografický záznam PRÁŠIL, Marek. Carl Orff: Carmina Burana [Carl Orff: Carmina Burana]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební Fakulta, Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie, rok 2017, s.58 Vedoucí diplomové práce prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel. Anotace Diplomová práce „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana“, jak již ze samotného názvu vyplývá, pojednává o skladateli Carlu Orffovi a jeho nejslavnější skladbě, kantátě Carmina Burana. V první části shrnuje život skladatele, stručně charakterizuje jeho dílo a kompoziční styl. Druhá část, věnovaná samotné kantátě, je zaměřena především na srovnání několika verzí kantáty. Jedná se o původní originální symfonickou verzi, autorizovanou komorní verzi, a pak také o transkripci pro symfonický dechový orchestr. Annotation The thesis „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana” deals with composer Carl Orff and his most famous composition the cantata of Carmina Burana, as is already clear from the title itself. In the first part the composer's life is summarized and briefly his work and compositional style are characterized. The second part is dedicated to the cantata itself, it is focused on comparing several versions of the cantatas. There is one original symphonic version, the Authorized chamber version, and a transcription for symphonic band. Klíčová slova Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, kantáta, symfonický orchestr, dechový orchestr, komorní ansámbl Keywords Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, cantata, symphonic orchestra, wind band (concert band), chamber ensemble Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval především MgA. -

American International School of Vienna Choral Program Invited to Perform Carmina Burana in New York City’S Avery Fisher Hall New York, N.Y

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: American International School of Vienna Choral Program Invited to Perform Carmina Burana in New York City’s Avery Fisher Hall New York, N.Y. – March 28, 2013 Outstanding music program Distinguished Concerts International New York City (DCINY) announced receives special invitation today that director Kathy Heedles and the American International School Choirs have been invited to participate in a performance of ‘Carmina Burana’ on the DCINY Concert Series in New York City. This performance at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall is on March 10, 2014. These outstanding musicians will join with other choristers to form the Distinguished Concerts Singers International, a choir of distinction. Conductor Vance George will lead the performance and will serve as the clinician for the residency. Why the invitation was extended Dr. Jonathan Griffith, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for DCINY states: “The American International School students and their director received this invitation because of the quality and high level of musicianship demonstrated by the singers on a previous performance of ‘O Fortuna’ from ‘Carmina Burana’. It is quite an honor just to be invited to perform in New York. These wonderful musicians not only represent a high quality of music and education, but they also become ambassadors for the entire community. This is an event of extreme pride for everybody and deserving of the community’s recognition and support.” The singers will spend 5 days and 4 nights in New York City in preparation for their concert. “The singers will spend approximately 9-10 hours in rehearsals over the 5 day residency.” says Griffith. -

Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2005 Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Lawrence Doebler Jeffrey Grogan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choral Union; Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra; Doebler, Lawrence; and Grogan, Jeffrey, "Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4790. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4790 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL UNION ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Lawrence Doebler, conductor CARMINA BURANA by Carl Orff Randie Blooding, baritone Deborah Montgomery-Cove, soprano Carl Johengen, tenor Ithaca College Women's Chorale, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Chorus, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler, conductor Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Grogan, conductor Charis Dimaris and Read Gainsford, pianists Members of the Ithaca Children's Choir Community School of Music and Arts Janet Galvan, artistic director Verna Brummett, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, April 17, 2005 4:00 p.m. ITHACA THE OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Samuel Barber Ithaca College Symphony -

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana Featuring the Choir and Percussion Ensembles of the Department of Music at the Université de Moncton; Monique Richard, conductor; Indian River Festival Chorus; Kelsea McLean, conductor; Danika Lorèn, soprano; Jonathan MacArthur, tenor; Adam Harris, baritone; Peter Tiefenbach, piano; and Robert Kortgaard, piano Sunday, July 10, 7:30pm Fogarty’s Cover Stan Rogers, arr. by Ron Smail I Dreamed of Rain Jan Garrett, arr. by Larry Nickel Praise His Holy Name Keith Hampton Embarquement pour Cythere Francis Poulenc Catching Shadows Ivan Trevino Misa Criolla Ariel Ramirez INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortune, Empress of the World 1. O Fortuna O Fortune 2. Fortune plango vulnera I lament the wounds that Fortune deals I. Primo vere In Spring 3. Veris leta facies The joyous face of Spring 4. Omnia Sol temperat All things are tempered by the Sun 5. Ecce gratum Behold the welcome Uf dem anger In the Meadow 6. Tanz Dance 7. Floret silva The forest flowers 8. Chramer, gip die varwe mir Monger, give me coloured paint 9. a) Reie Round dance b) Swaz hie gat umbe They who here go dancing around c) Chume, chum, geselle min Come, come, my dear companion d) Swaz hie gat umbe (reprise) They who here go dancing around 10. Were diu werlt alle min If the whole world were but mine II. In Taberna In the Tavern 11. Estuans interius Seething inside 12. Olim lacus colueram Once I swam in lakes 13. Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis I am the abbot of Cockaigne 14. In taberna quando sumus When we are in the tavern III. -

Mouvance and Authorship in Heinrich Von Morungen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87n0t2tm Author Fockele, Kenneth Elswick Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Niklaus Largier, chair Professor Elaine Tennant Professor Frank Bezner Fall 2016 Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang © 2016 by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Abstract Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Niklaus Largier, Chair Despite the centrality of medieval courtly love lyric, or Minnesang, to the canon of German literature, its interpretation has been shaped in large degree by what is not known about it—that is, the lack of information about its authors. This has led on the one hand to functional approaches that treat the authors as a class subject to sociological analysis, and on the other to approaches that emphasize the fictionality of Minnesang as a form of role- playing in which genre conventions supersede individual contributions. I argue that the men who composed and performed these songs at court were, in fact, using them to create and curate individual profiles for themselves. -

“O Fortuna” from Carl Orff's Carmina Burana Movement Idea by Cristi Cary Miller

“O Fortuna” from Carl Orff's Carmina Burana Movement Idea by Cristi Cary Miller May be used with the listening lesson for “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana by Carl Orff in the October/November 2010, Volume 11, No. 2 issue of Music Express. Formation: Partners forming concentric circles, inside circle facing outward. Each dancer holds a scarf in right hand. INTRO “O Fortuna”: Outside circle slowly raises scarf in the air and waves it R/L. “Velut luna”: Inside circle repeats action. “Statu variabilis”: With arms still raised above head, partners circle each other CW and return to starting position, facing to their R. SECTION ONE Line 1 Beats 1-6: Circles walk to their R (inside CCW, outside CW), waving scarves downward L/R on the beats. Beats 7-12: All turn in place with scarves in air. Line 2 Beats 1-6: Repeat above going in opposite direction and back to part- ners. Beats 7-12: All turn in place with scarves in air. Line 3 Beats 1-12: Circles walk to their R, waving scarves downward L/R on the beats, stopping at partners on opposite side of circle. SECTION TWO Line 1 Beats 1-6: Outside circle only walks to their R, waving scarves down- ward L/R on the beats; inside circle stays in place. Beats 7-12: Outside circle dancers turn in place with scarves in the air and hold position. Line 2 Beats 1-6: Inside circle only walks to their R, waving scarves downward L/R on the beats; outside circle stays in place. -

Of Music PROGRAM

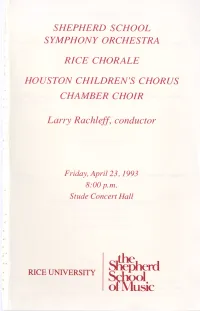

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICE CHORALE HOUSTON CHILDREN'S CHORUS CHAMBER CHOIR Larry Rachleff, conductor Friday, April23, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall "-' sfkteherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Fanfare for a Great City Arthur Gottschalk (b. 1952) Variations on a Theme of Joseph Haydn, Op. 56a Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff ( 1895-1982) Rice Chorale Houston Children's Chorus Chamber Choir Kelley Cooksey, soprano Francisco Almanza, tenor Robert Ames, baritone In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) Oboe Trumpet (cont.) Julie Savignon, Erwin Foubert Margaret Butler Troy Rowley concertmaster Patrick Horn Kyle Bruckmann David Workman Claudia Harrison Stephanie Griffin Jeffrey Champion Trombone Barbara Wittenberg Bin Sun Dione Chandler Wade Demmert Jeanine Tiemeyer Andrew Weaver Karen Friedman David Ford Kristin Lacey Sharon Neufeld ~ Brent Phillips Mihaela Oancea English Horn Cello Kyle Bruckmann Inga Ingver Tuba Katherine de Bethune, Yenn Chwen Er Clarinet Jeffrey Tomberg principal Yoong-han Chan Benjamin Brady Danny Urban ~ Jeanne Jaubert Magdalena Villegas Joanne Court Scott Brady Timpani and Tanya Schreiber Kelly Cramm Mary Ellen Morris Percussion Rebecca Ansel Martin van Maanen Robin Creighton Douglas Cardwell Eitan Ornoy X in-Yang Zhou Amy -

Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortuna, Herrscherin Der Welt

CARMINA BURANA TEXT ÜBERSETZTUNG Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortuna, Herrscherin der Welt 1. O Fortuna Schicksal O Fortuna velut Luna Schicksal, wie der Mond dort oben, statu variabilis, so veränderlich bist Du, semper crescis aut decrescis ; wächst Du immer oder schwindest!- vita detestabilis Schmählich ist das Leben hier! nunc obdurat et tunc curat Erst misshandelt, dann verwöhnt es ludo mentis aciem, spielerisch den schwachen Sinn. egestatem, potestatem Dürftigkeit, Grossmächtigkeiten, dissolvit ut glaciem. schmilzet es, als wär’s nur Eis. Sors immanis et inanis, Schicksal, ungeschlacht und eitel, rota tu volubilis, bist ein immer rollend Rad: status malus vana salus schlimm Dein Wesen, Glück als Wahn bloss, semper dissolubilis, fort bestehend im Zergehen! obumbrata et velata Überschattet und verschleiert michi quoque niteris ; überkommst Du gar auch mich. nunc per ludum dorsum nudum Durch Dein Spiel mit schierer Bosheit fero tui sceleris. trag ich meinen Buckel nackt. Sors salutis et virtutis Wohlergehen, rechter Wandel michi nunc contraria sind zuwider mir zurzeit. est affectus et defectus Wie mein Will’, so meine Schwäche semper in angaria. finden sich in Sklaverei. Hac in hora sine mora Drum zur Stunde ohne Säumen corde pulsum tangite ; greifet in die Saiten Ihr! quod per sortem sternit fortem, Dass das Schicksal auch den Starken mercum omnes plangite ! Hinstreckt: Das beklagt mit mir! 2. Fortunae plango vulnera Die Wunden, die Fortuna schlug Fortunae plango vulnera Die Wunden, die Fortuna schlug, stillantibus ocellis, beklag’ich feuchten Auges, quod sua michi munera weil sie mir missgesinnt entzieht, subtrahit rebellis. was sie mir selbst gegeben. Verum est, quod legitur Wahr ist’s, was man lesen kann fronte capillata, von dem Schopf des Glückes, sed plerumque sequitur meist zeigt die Gelegenheit occasio calvata. -

新古典主義(Neo-Classicism)與卡爾奧福(Carl Orff)的布蘭詩歌(Carmina

新古典主義(Neo-classicism)與卡爾奧福 (Carl Orff)的布蘭詩歌(Carmina Burana) 高千珊 目 次 目 次 ........................................................................................ I 前 言 ........................................................................................ 1 一、新古典主義音樂 .............................................................. 2 二、卡爾‧奧福的生平 .......................................................... 6 三、布蘭詩歌 ......................................................................... 10 四、結 語 ............................................................................. 25 參考資料 .................................................................................. 26 【附錄一】 ............................................................................. 29 I 前 言 卡爾‧奧福 ( Carl Burana , 1895-1982 ) 是 20 世紀著名的德國作曲家,更是 重要的音樂教育家,在他 87 年的音樂生涯中,透過長期的創作實踐與不斷的研 究探索,寫下許多著名的作品,而《布蘭詩歌》( Carmina Burana , 1937 ) 更是他 在音樂創作上一部重要的代表作。這部以中世紀詩歌為題材的大型作品,奧福將 中世紀、巴洛克及二十世紀這三個時空巧妙結合,以簡潔的節奏及特殊的音樂語 言創作出獨特的音樂風格。身為音樂老師的我,卡爾‧奧福這個名字早已十分熟 悉,但對於他的生平和他所處的時空背景,以及所創作的樂曲卻感到陌生,所以 本文將以此作為了解的重點,並試圖探究其作品《布蘭詩歌》。在結構上,本文 共分為四個部份,在第一部份中,本文將對二十世紀的新古典主義加以說明;第 二部份則針對卡爾‧奧福的生平做一介紹;第三部份則以《布蘭詩歌》為例,進 行分析與研究。 1 一、新古典主義音樂 十九世紀,科學的快速進步,電報、電話、錄音器材與無線電的發明,拉近 了東西方國家的距離,也間接增加對各民族間音樂的認識;而鐵路與汽車工業的 突飛猛進,也使經濟快速發展起來。進入二十世紀後,科技與工業持續進步,飛 機、汽車、收錄音機以及電話……等的普遍使用,將人們的生活徹底改變。自然 科學上,愛因斯坦的相對論及量子力學1的研究結果,則改變人們對物質結構的 概念以及對宇宙及世界的認知。而 1914 年的第一次世界大戰,使得許多國家經 歷社會與政治的動盪與不安,也改變了世界政治的權利結構。 西方音樂上,在歷經十九世紀浪漫主義音樂的洗禮,調性、和聲的使用達至 巔峰,社會與科技的發展與改變,也影響音樂家們去思索音樂未來的新方向。隨 著浪漫主義的式微,緊接而來的第一次世界大戰,使得新的生活型態及社會價值 漸漸形成,西方的文學、哲學、繪畫、舞蹈及音樂出現許多新的思潮,音樂的發 -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1995

osfon i^j^ny wksW Tangtew@» 5 NOW AT FILENE'S... FROM TOMMY H i The tommy collection i Cologne spray, 3.4-oz.,$42 Cologne spray, 1.7-oz.,$28 After-shave balmB mm 3.4-oz., $32 m After-shave, 3.4-oz., $32 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Fourteenth Season, 1994-95 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Nina L. Doggett Harvey Chet Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Dean W. Freed Krentzman Carol Scheifele-Holmes Julian Cohen AvramJ. Goldberg George Krupp Richard A. Smith William F. Connell Thelma E. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Julian T. Houston Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps Mrs. George I. Mrs. George Lee Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Kaplan Sargent David B. Arnold, Jr. Fahnestock George H. Kidder Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Mrs. John L. Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey Abram T. Collier Grandin Irving W. Rabb John L. Thorndike Nelson J. Darling, Jr. Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. McDonough, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Board of Overseers of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thelma E. Goldberg, Chairman Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Jordan L. -

Symphony Band Chamber Winds Michael Haithcock, Conductor

SYMPHONY BAND CHAMBER WINDS MICHAEL HAITHCOCK, CONDUCTOR NICHOLAS BALLA, KIMBERLY FLEMING & JOANN WIESZCZYK, GRADUATE STUDENT CONDUCTORS Friday, February 12, 2021 Hill Auditorium 8:00 PM Il barbiere di Siviglia: Overture (1816) Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) arr. Wenzel Sedlak JoAnn Wieszczyk, conductor Three Dances and Final Scene from Der Mond (1939) Carl Orff Dance 1 (1895–1982) Dance 2 arr. Friedrich K. Wanek Final Scene Dance 3 JoAnn Wieszczyk, conductor Selene (Moon Chariot Rituals) (2015) Augusta Reed Thomas (b. 1964) arr. Cliff Colnot Intermission Timbuktuba (1995) Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Nicholas Balla, conductor Bull’s-Eye (2019) Viet Cuong (b. 1990) Kimberly Fleming, conductor Symphony for Brass and Timpani (1956) Herbert Haufrecht Dona Nobis Pacem (1909–1998) Elegy Jubilation THe use of all cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Please turn off all cell phones and pagers or set ringers to silent mode. ROSSINI, IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: OVERTURE If the music of Rossini’s overture to Il barbiere di Siviglia (THe Barber of Seville) seems to have a peculiar amount of swashbuckling surge and vigor for a comic opera prelude, it is because the overture originally was composed for an earlier opera, Aureliano in Palmira, a historical work based on the Crusades. In fact, it is believed that Rossini used this music two other times be- fore this opera. The composer’s recycling provides an interesting contrast with Beethoven, who composed four different overtures before arriving at a final version for his only opera,Fidelio . The once-perceivedSturm und Drang of Rossini’s overture has been blunted by association, not only by the composer’s accompanying setting of the Beaumarchais comedy, but also by its jocular appearances in a Bugs Bunny cartoon, the Beatles’ filmHelp , and an episode of Seinfeld.