PAPERS in PIDGIN and CREOLE LINGUISTICS No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer Learning for Singlish Universal Dependencies Parsing and POS Tagging

From Genesis to Creole language: Transfer Learning for Singlish Universal Dependencies Parsing and POS Tagging HONGMIN WANG, University of California Santa Barbara, USA JIE YANG, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore YUE ZHANG, West Lake University, Institute for Advanced Study, China Singlish can be interesting to the computational linguistics community both linguistically as a major low- resource creole based on English, and computationally for information extraction and sentiment analysis of regional social media. In our conference paper, Wang et al. [2017], we investigated part-of-speech (POS) tagging and dependency parsing for Singlish by constructing a treebank under the Universal Dependencies scheme, and successfully used neural stacking models to integrate English syntactic knowledge for boosting Singlish POS tagging and dependency parsing, achieving the state-of-the-art accuracies of 89.50% and 84.47% for Singlish POS tagging and dependency respectively. In this work, we substantially extend Wang et al. [2017] by enlarging the Singlish treebank to more than triple the size and with much more diversity in topics, as well as further exploring neural multi-task models for integrating English syntactic knowledge. Results show that the enlarged treebank has achieved significant relative error reduction of 45.8% and 15.5% on the base model, 27% and 10% on the neural multi-task model, and 21% and 15% on the neural stacking model for POS tagging and dependency parsing respectively. Moreover, the state-of-the-art Singlish POS tagging and dependency parsing accuracies have been improved to 91.16% and 85.57% respectively. We make our treebanks and models available for further research. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

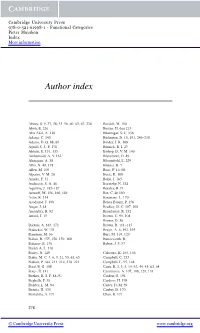

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Vowel and Consonant Lessening: a Study of Articulating Reductions

Title: Vowel and Consonant Lessening: A Study of Articulating Reductions and Their Relations to Genders Author name(s): Grace Hui Chin Lin & Paul Shih Chieh Chien General Education Center, China Medical University (Lin) English Department, Changhwa University of Education General Education Center, Taipei Medical University (Chien) Academic Writing Education Center, National Taiwan University Page Number: p. 70-81 Publication date: 2011, Dec. 20 Conference information for conference papers (name, date and location of the conference) : Name : International Conference on Computer Assisted Language Learning in 2011, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology Date: Nov. 5, 2011, Location: Yunlin, Taiwan 69 Vowel and Consonant Lessening: A Study of Articulating Reductions and Their Relations to Genders Grace Hui Chin Lin Paul Shih Chieh Chien ABSTRACT Using English as a global communicating tool makes Taiwanese people have to speak in English in diverse international situations. However, consonants and vowels in English are not all effortless for them to articulate. This phonological reduction study explores concepts about phonological (articulating system) approximation. From Taiwanese folks’ perspectives, it analyzes phonological type, rate, and their associations with 2 genders. This quantitative research discovers Taiwanese people’s vocalization problems and their facilitating solutions by articulating lessening. In other words, this study explains how English emerging as a global language can be adapted and fluently articulated by Taiwanese. It was conducted at National Changhwa University of Education from 2010 fall to 2011 spring, investigating Taiwanese university students’ phonological lessening systems. It reveals how they face the phonetics challenges during interactions and give speeches by ways of phonological lessening. Taiwanese folks’ lessening patterns belong to simplified pronouncing methods, being evolved through Mandarin, Hakka, and Holo phonetic patterns. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

'Speaking Singlish' Comic Strips

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 12, 2020 The Use of Colloquial Singaporean English in ‘Speaking Singlish’ Comic Strips: A Syntactic Analysis Delianaa*, Felicia Oscarb, a,bEnglish department, Faculty of Cultural Studies, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Email: a*[email protected] This study explores the sentence structure of Colloquial Singaporean English (CSE) and how it differs from Standard English (SE). A descriptive qualitative method is employed as the research design. The data source is the dialogue of five comic strips which are purposively chosen from Speaking Singlish comic strips. Data is in the form of sentences totalling 34 declaratives, 20 wh- interrogatives, 14 yes -no interrogatives, 3 imperatives and 1 exclamative. The results present the sentence structure of CSE found in the data generally constructed by one subject, one predicate, and occasionally one discourse element. The subject is a noun phrase while the predicate varies amongst noun, adjective, adverb, and verb phrases– particularly in copula deletion. On the other hand, there are several differences between the sentence structure of CSE and SE in the data including the use of copula, topic sentence, discourse elements, adverbs, unmarked plural noun and past tense. Key words: Colloquial Singaporean English (CSE), Speaking Singlish, sentence structure. Introduction Standard English (SE) is a variety of the English language. This view is perhaps more acceptable in the case of Non-Standard English (NSE). The classification of SE being a dialect goes against the lay understanding that a dialect is a subset of a language, usually with a geographical restriction regarding its distribution (Kerswill, 2006). -

Does Singlish Contribute to Singaporean's National Identity

International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development Vol. 9 , No. 2, 2020, E-ISSN: 2226-6348 © 2020 HRMARS Does Singlish Contribute to Singaporean’s National Identity, and do Singaporeans Support Formal Recognition of it? Wang Shih Ching To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v9-i2/7244 DOI:10.6007/IJARPED/v9-i2/7244 Received: 15 Jan 2020, Revised: 15 Feb 2020, Accepted: 10 Mar 2020 Published Online: 23 Mar 2020 In-Text Citation: (Wang, 2020) To Cite this Article: Wang, S. C. (2020). Does Singlish Contribute to Singaporean’s National Identity, and do Singaporeans Support Formal Recognition of it? International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 9(2), 96–112. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9(2) 2020, Pg. 96 - 112 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARPED JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 96 International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development Vol. 9 , No. 2, 2020, E-ISSN: 2226-6348 © 2020 HRMARS Does Singlish Contribute to Singaporean’s National Identity, and do Singaporeans Support Formal Recognition of it? Wang Shih Ching Research Scholar, Faculty of Social Science, Arts and Humanities, Lincoln University College, Malaysia Abstract ‘Singlish’ is a colloquial form of English that was influenced by other languages used in Singapore, such as Chinese Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. -

Multilingual Cameroon

GOTHENBURG AFRICANA INFORMAL SERIES – NO 7 ______________________________________________________ Multilingual Cameroon Policy, Practice, Problems and Solutions by Tove Rosendal DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES 2008 2 Contents List of tables ..................................................................................................................... 4 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2. Focus, methodology and earlier studies ................................................................. 11 3. Language policy in Cameroon – historical overview............................................. 13 3.1 Pre-independence period ................................................................................ 13 3.2 Post-independence period............................................................................... 13 4. The languages of Cameroon................................................................................... 14 4.1 The national languages of Cameroon - an overview ...................................... 14 4.1.1 The language families of Cameroon....................................................... 16 4.1.2 Languages of wider distribution............................................................ -

Singlish to English

TO English Singlish In a country like Singapore, where a non-native language is adopted as a native language, the style, vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, etc. will have its own flavour and even its own unique code of usage, like a grammar. This chapter will focus on specific problems students have when studying English in Singapore. A comparison will be made between standard English and Singlish in terms of structure and form. It should be noted that Singlish and Singapore English are two very different things. A person who speaks Singapore English uses standard grammar and vocabulary but pronounces words the way most Singaporean English speakers do. Singlish, on the other hand, includes the same kind of pronunciation, although Singlish speakers may have a stronger accent in that some sounds are changed or dropped entirely. 1. CAN and the omission of the subject. In Chinese, the verb “can” has different meanings. One means ability (I can speak English) and the other meaning possibility (We can go now) or permission (We can’t smoke here), etc. The biggest difference in these expressions between Chinese and English (and Malay too) is that in Chinese and Malay, “can” is sometimes used without the subject, as it is not necessary when the meaning is understood. Also, in Chinese, a simple question marker “mah” is used to make questions (in Malay, it is necessary only to change intonation for a question). This “mah” cannot be translated into a word in English because we change word order and intonation to make questions. The result is often sentences like these: Can go? This one can? Can? Cannot. -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Kodrah Kristang: the Initiative to Revitalize the Kristang Language in Singapore

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.35–121 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 2 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24906 Kodrah Kristang: The initiative to revitalize the Kristang language in Singapore Kevin Martens Wong National University of Singapore Abstract Kristang is the critically endangered heritage language of the Portuguese-Eurasian community in Singapore and the wider Malayan region, and is spoken by an estimated less than 100 fluent speakers in Singapore. In Singapore, especially, up to 2015, there was almost no known documentation of Kristang, and a declining awareness of its existence, even among the Portuguese-Eurasian community. However, efforts to revitalize Kristang in Singapore under the auspices of the community-based non-profit, multiracial and intergenerational Kodrah Kristang (‘Awaken, Kristang’) initiative since March 2016 appear to have successfully reinvigorated community and public interest in the language; more than 400 individuals, including heritage speakers, children and many people outside the Portuguese-Eurasian community, have joined ongoing free Kodrah Kristang classes, while another 1,400 participated in the inaugural Kristang Language Festival in May 2017, including Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and the Portuguese Ambassador to Singapore. Unique features of the initiative include the initiative and its associated Portuguese-Eurasian community being situated in the highly urbanized setting of Singapore, a relatively low reliance on financial support, visible, if cautious positive interest from the Singapore state, a multiracial orientation and set of aims that embrace and move beyond the language’s original community of mainly Portuguese-Eurasian speakers, and, by design, a multiracial youth-led core team.