Case Studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biomass Burning and Water Balance Dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin in Africa

Article Biomass Burning and Water Balance Dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin in Africa Forrest W. Black 1 , Jejung Lee 1,*, Charles M. Ichoku 2, Luke Ellison 3 , Charles K. Gatebe 4 , Rakiya Babamaaji 5, Khodayar Abdollahi 6 and Soma San 1 1 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA; [email protected] (F.W.B.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Graduate Program, College of Arts & Sciences, Howard University, Washington, DC 20059, USA; [email protected] 3 Science Systems and Applications, Inc., Lanham, MD 20706, USA; [email protected] 4 Atmospheric Science Branch SGG, NASA Ames Research Center, Mail Code 245-5, ofc. 136, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA; [email protected] 5 National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA), PMB 437, Abuja, Nigeria; [email protected] 6 Faculty of Natural Resources and Earth Sciences, Shahrekord University, P.O. Box 115, Shahrekord 88186-34141, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-816-235-6495 Abstract: The present study investigated the effect of biomass burning on the water cycle using a case study of the Chari–Logone Catchment of the Lake Chad Basin (LCB). The Chari–Logone catchment was selected because it supplies over 90% of the water input to the lake, which is the largest basin in central Africa. Two water balance simulations, one considering burning and one without, were compared from the years 2003 to 2011. For a more comprehensive assessment of the effects of burning, albedo change, which has been shown to have a significant impact on a number of Citation: Black, F.W.; Lee, J.; Ichoku, environmental factors, was used as a model input for calculating potential evapotranspiration (ET). -

Leadership, Followership, and Evolution Some Lessons from the Past

Leadership, Followership, and Evolution Some Lessons From the Past Mark Van Vugt University of Kent Robert Hogan Hogan Assessment Systems Robert B. Kaiser Kaplan DeVries Inc. This article analyzes the topic of leadership from an evo- Second, the literature focuses on leaders and tends to lutionary perspective and proposes three conclusions that ignore the essential role of followers (Hollander, 1992; are not part of mainstream theory. First, leading and Yukl, 2006). Third, research largely concentrates on prox- following are strategies that evolved for solving social imate issues of leadership (e.g., What makes one person a coordination problems in ancestral environments, includ- better leader than others?) and rarely considers its ultimate ing in particular the problems of group movement, intra- functions (e.g., How did leadership promote survival and group peacekeeping, and intergroup competition. Second, reproductive success among our ancestors?) (R. Hogan & the relationship between leaders and followers is inher- Kaiser, 2005). Finally, there has been little cross-fertiliza- ently ambivalent because of the potential for exploitation of tion between psychology and disciplines such as anthro- followers by leaders. Third, modern organizational struc- pology, economics, neuroscience, biology, and zoology, tures are sometimes inconsistent with aspects of our which also contain important insights about leadership evolved leadership psychology, which might explain the (Bennis, 2007; Van Vugt, 2006). alienation and frustration of many citizens and employees. This article offers a view of leadership inspired by The authors draw several implications of this evolutionary evolutionary theory, which modern scholars increasingly analysis for leadership theory, research, and practice. see as essential for understanding social life (Buss, 2005; Lawrence & Nohria, 2002; McAdams & Pals, 2006; Nettle, Keywords: evolution, leadership, followership, game the- 2006; Schaller, Simpson, & Kenrick, 2006). -

Beowulf and Competitive Altruism,” P

January 2013 Volume 9, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of Editor (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ~ Editorial Board ~▪▪~ Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. THIS ISSUE FEATURES Kevin Brown, Ph.D. Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. † Eric Luttrell, “Modest Heroism: Beowulf and Competitive Altruism,” p. 2 Cheryl L. Jaworski, M.A. † Dena R. Marks, “Secretary of Disorientation: Writing the Circularity of Belief in Elizabeth Costello,” p.11 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † Margaret Bertucci Hamper, “’The poor little working girl’: The New Woman, Chloral, and Motherhood in The House of Mirth,” p. 19 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Kristin Mathis, “Moral Courage in The Runaway Jury,” p. 22 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † William Bamberger, “A Labyrinthine Modesty: On Raymond Roussel Michelle Scalise Sugiyama, and Chiasmus,” p. 24 Ph.D. ~▪~ Editorial Interns † St. Francis College Moral Sense Colloquium: - Program Notes, p. 27 Tyler Perkins - Kristy L. Biolsi, “What Does it Mean to be a Moral Animal?”, p. 29 - Sophie Berman, “Science sans conscience n’est que ruine de l’âme,” p.36 ~▪~ Kimberly Resnick † Book Reviews: - Lisa Zunshine, editor, Introduction to Cognitive Cultural Studies. Gregory F. Tague, p. 40 - Edward O. Wilson, The Social Conquest of Earth. Wendy Galgan, p. 42 ~▪~ ~ Contributor Notes, p. 45 Announcements, p. 45 ASEBL Journal Copyright©2013 E-ISSN: 1944-401X *~* [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com ASEBL Journal – Volume 9 Issue 1, January 2013 Modest Heroism: Beowulf and Competitive Altruism Eric Luttrell Christian Virtues or Human Virtues? Over the past decade, adaptations of Beowulf in popular media have portrayed the eponymous hero as a dim-witted and egotistical hot-head. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

1 December 19, 2019 the Psychology of Online Political Hostility

The Psychology of Online Political Hostility: A Comprehensive, Cross-National Test of the Mismatch Hypothesis Alexander Bor* & Michael Bang Petersen Department of Political Science Aarhus University August 30, 2021 Please cite the final version of this paper published in the American Political Science Review at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000885. Abstract Why are online discussions about politics more hostile than offline discussions? A popular answer argues that human psychology is tailored for face-to-face interaction and people’s behavior therefore changes for the worse in impersonal online discussions. We provide a theoretical formalization and empirical test of this explanation: the mismatch hypothesis. We argue that mismatches between human psychology and novel features of online environments could (a) change people’s behavior, (b) create adverse selection effects and (c) bias people’s perceptions. Across eight studies, leveraging cross-national surveys and behavioral experiments (total N=8,434), we test the mismatch hypothesis but only find evidence for limited selection effects. Instead, hostile political discussions are the result of status-driven individuals who are drawn to politics and are equally hostile both online and offline. Finally, we offer initial evidence that online discussions feel more hostile, in part, because the behavior of such individuals is more visible than offline. Acknowledgements This research has benefitted from discussions with Vin Arceneaux, Matt Levendusky, Mark Van Vugt, John Tooby, and members of the Research on Online Political Hostility (ROHP) group, among many others. We are grateful for constructive comments to workshop attendees at the Political Behavior Section of Aarhus University, at the NYU-SMAPP Lab, at the NYU Social Justice Lab, at the Hertie School, and to conference audiences at APSA 2019, HBES 2019, and ROPH 2020. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

127 WHITE FULANI CATTLE OF WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA C.L. Tawah' and J.E.O. Rege2 'Centre for Animal and Veterinary Research. P.O. Box 65, Ngaoundere, Adamawa Province, CAMEROON 2International Livestock Research Institute, P.O. Box 5689, Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA SUMMARY The paper reviews information on the White Fulani cattle under the headings: origin, classification, distribution, population statistics, ecological settings, utility, husbandry practices, physical characteristics, special genetic characteristics, adaptive attributes and performance characteristics. It was concluded that the breed is economically important for several local communities in many West and Central African countries. The population of the breed is substantial. However, introgression from exotic cattle breeds as well as interbreeding with local breeds represent the major threat to the breed. The review identified a lack of programmes to develop the breed as being inimical to its long-term existence. RESUME L'article repasse l'information sur la race White Fulani du point de vue: origine, classement, distribution, statistique de population, contexte écologique, utilité, pratiques de conduites, caractéristiques physiques, caractéristiques génétiques spéciales, adaptabilité, et performances. On conclu que la race est importante du point de vue économique pour diverses communautés rurales dans la plupart des régions orientales et centrale de l'Afrique. Le nombre total de cette race est important; cependant, l'introduction de races exotiques, ainsi que le croisement avec des races locales représente le risque le plus important pour cette race. Cet article souligne également le fait que le manque de programmes de développement à long terme représente un risque important pour la conservation de cette race. -

Cameroon 2014 Table A

Cameroon 2014 Table A: Total funding and outstanding pledges* as of 29 September 2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R10) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and appealing organizations. Donor Channel Description Funding Outstanding Pledges USD USD Allocation of unearmarked funds by FAO The assistance is intended to cover the immediate needs of 493,000 0 FAO refugees and host populations on agricultural inputs to enable households engaged in agricultural activities boost vegetable production during the off-season 2014 (August to November). This should improve food security and generate income through the sale of surpluses. In addition, in order to promote a more sustainable approach, the project will provide cereals and cassava processing facilities in host villages, coupled with training sessions. This will reduce post-harvest losses in corn and cassava, and thus help to strengthen the resilience of target populations. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation IMC to respond to the cholera outbreak in the Far North region in 900,000 0 Cameroon and to address the humanitarian needs of CAR refugees in the East and Adamawa regions of Cameroon Canada IFRC IFRC DREF operation MDRCM015 in Cameroon - IFRC 32,802 0 December 2013 operation to assist CAR refugees in Cameroon (M013807) Carry-over (donors not specified) WFP to be allocated to specific project 31,201 0 Central Emergency Response Fund WHO Medical assistance to local communities and refugees in 55,774 0 response to ongoing nutritional crisis, cholera and measles -

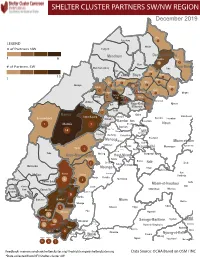

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Multilingual Cameroon

GOTHENBURG AFRICANA INFORMAL SERIES – NO 7 ______________________________________________________ Multilingual Cameroon Policy, Practice, Problems and Solutions by Tove Rosendal DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES 2008 2 Contents List of tables ..................................................................................................................... 4 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2. Focus, methodology and earlier studies ................................................................. 11 3. Language policy in Cameroon – historical overview............................................. 13 3.1 Pre-independence period ................................................................................ 13 3.2 Post-independence period............................................................................... 13 4. The languages of Cameroon................................................................................... 14 4.1 The national languages of Cameroon - an overview ...................................... 14 4.1.1 The language families of Cameroon....................................................... 16 4.1.2 Languages of wider distribution............................................................ -

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Paix

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work - Fatherland MINISTRY OF MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2017 OF THE MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT SUBSECTOR FOREWORD The Ministry of Mines, Industry and Technological Development is pleased to present the statistical yearbook of the Mines, Industry and Technological Development sub-sector, MIDTSTAT, 2017edition. Its aim is to put at the disposal of actors of the sub-sector on the one hand, and of the general public, on the other hand, statistical data which illustrate the actions and development policies implemented in this ministerial department. The document presents a series of statistical information relating, on the one hand, to contextual data on Cameroon and, on the other hand, to the mines, industry and technological development components. I, therefore, invite all potential users of the information contained in this valuable document to make good use of it, and to generate actions likely to further improve the performance of our sub-sector. I would like to seize this opportunity to express my appreciation to all those who have, in one way or another, contributed towards elaborating this document, in particular the National Institute of Statistics for its support, the central and devolved services of MINMIDT, structures under its supervisory authority, as well as the administrations called upon to provide statistical information. We welcome suggestions and contributions likely to enrich and improve -

Situation of Nigerian Refugees in the NW and Adamawa Regions Of

Situation of Nigerian Refugees in the NW and Adamawa Regions of Cameroon Conflict over land between the Pastoral Mbororo Fulani and the Mambilas in the Taraba State of Nigeria has been existing for more than three decades. The Mambilas claim they own the land and have more power to control the land and related resources. Conflicts have been frequent with no peaceful cohabitation between them. The civil war started between them in 1982, 2001-2002 and the third and the fiercest erupted on 17-23 June 2017 with huge human and material losses. The Mambila militia men brutally attacked the Fulani and more than 200 Mbororo people killed, 150 severely injured with machete wounds, 180 homesteads looted and burndown, 20.000 herds of cattle killed, maimed or stolen and 10,000 people displaced and 6000 people seek refuge in Cameroon. Killing and looting is still going. 90 cases treated by the integrated health Centre Atta and 46 cases handles by catholic Health Centre Atta 3 people currently taking treatment at BBH Banso and two in the Integrated Health Centre Atta Hosting Regions The refugees are found in several villages in Nwa sub division in the North West Region In the Adamawa region, they are found in 3 sub divisions of the Adamawa region ie Bankim, Mayo Dalle and Banyo central all in Mayo Banyo division. MBOSCUDA intervenes and provided in emergency relief support of food items such as rice, cooking oil, maggi, savon, salt, tomatoes, cloths and beddings The able below shows the number of Refugees per village in areas of MBOSCUDA’s intervention