Model Citizens: Fisherfolk Imagery from West Cornwall, 1860-1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover and Plan: Art and Culture

DISCOVER AND PLAN: ART AND CULTURE Penzance a and Newlyn have been associated with art and culture for centuries with the Newlyn School of Artists and it is still an area which has a thriving arts community. With a plethora of independent galleries and studios to peruse and meet artists, an arts festival and eclectic performance arts scene, there is no better place to immerse yourself in beautiful scenery and thought provoking art. PENLEE OPEN AIR THEATRE Located within Penlee Gardens is Penlee Park Open WHERE TO STAY? Air theatre which is a truly unique experience, that has celebrated Cornish, national and international performers There is a wide variety of accommodation in since 1948. Music, humour and plays all delivered in a Penzance and surrounding area, something to spring, summer and autumn programme. suit all tastes and budgets. lovepenzance.co.uk/stay PENLEE HOUSE GALLERY AND MUSEUM Museum exhibits sit alongside an impressive art collection with works by members of the famous Newlyn School. WHERE TO EAT? One of the gallery’s most famous paintings is “The Rain Described as ‘Cornwall’s new gourmet capital’, it Raineth Every Day” by Norman Garstin, which depicts waves and rain whipping across walkers on Penzance Penzance is well known for its fantastic food Promenade and Drink which has been built around local A great place to grab a cup of team and slice of cake at and ethical sourcing of ingredients delivering the Orangery Cafe, Penlee House. some of the region’s most exciting Pubs, bars, NEWLYN FILM HOUSE cafes, delis, and restaurants. -

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue Location Title Auth. Last Notes Magazine - American Ancestors 4 issues. A local history book and is a record of the pioneer days of the 80 Years of Progress (Westlock, AB Committee Westlock District. Many photos and family stories. Family Alberta) name index. 929 pgs History of Kingman and Districts early years in the 1700s, (the AB A Harvest of Memories Kingman native peoples) 1854 the Hudson Bay followed by settlers. Family histories, photographs. 658 pgs Newspapers are arranged under the place of publication then under chronological order. Names of ethnic newspapers also AB Alberta Newspapers 1880 - 1982 Strathern listed. Photos of some of the newspapers and employees. 568 pgs A history of the Lyalta, Ardenode, Dalroy Districts. Contains AB Along the Fireguard Trail Lyalta photos, and family stories. Index of surnames. 343 pgs A local history book on a small area of northwestern Alberta from Flying Shot to South Wapiti and from Grovedale to AB Along the Wapiti Society Klondyke Trail. Family stories and many photos. Surname index. 431 pgs Alberta, formerly a part of the North-West Territories. An An Index to Birth, Marriage & Death AB Alberta index to Birth, Marriage and Death Registrations prior to Registrations prior to 1900 1900. 448 pgs AB Ann's Story Clifford The story of Pat Burns and his ranching empire. History of the Lower Peace River District. The contribution of AB Around the Lower Peace Gordon the people of Alberta, through Alberta Culture, acknowledged. 84 pgs Illustrated Starting with the early settlers and homesteaders, up to and AB As The Years Go By... -

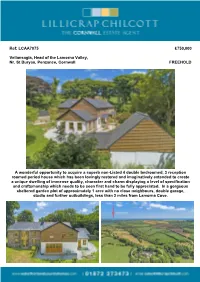

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000

Ref: LCAA7075 £750,000 Vellansagia, Head of the Lamorna Valley, Nr. St Buryan, Penzance, Cornwall FREEHOLD A wonderful opportunity to acquire a superb non-Listed 4 double bedroomed, 3 reception roomed period house which has been lovingly restored and imaginatively extended to create a unique dwelling of immense quality, character and charm displaying a level of specification and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. In a gorgeous sheltered garden plot of approximately 1 acre with no close neighbours, double garage, studio and further outbuildings, less than 2 miles from Lamorna Cove. 2 Ref: LCAA7075 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: covered entrance porch into huge open-plan kitchen/dining room/family room (28’7” x 24’2”), larder, utility room, wc, triple aspect garden room, sitting room (26’4” x 16’6”) with woodburning stove. First Floor: approached off two separate staircases, galleried landing, master bedroom with en-suite bathroom, guest bedroom with en-suite shower room, circular staircase leads to secondary first floor landing, two further double bedrooms, family bathroom. Outside: double garage and workshop. Timber studio. Traditional stone outbuilding. Parking for numerous vehicles. Generous lawned gardens bounded by mature deciduous tree borders and pond. In all, approximately, 1 acre. DESCRIPTION • The availability of Vellansagia represents an incredibly exciting opportunity to acquire a truly unique family home comprising a lovingly restored non-Listed period house which has been transformed with a beautiful, contrasting large modern extension (more than doubling the size of the original house). Displaying a superb bespoke standard of finish and craftsmanship which needs to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk . o. (ORPORATfON OF Londoi 7IRTG7ILLE1? IgpLO G U i OF THE LOAN COLLECTIO o f Picture 1907 PfeiCE Sixpence <Art Gallery of the (Corporation o f London. w C a t a l o g u e of the Exhibition of Works by Danish Painters. BY A. G. TEMPLE, F.S.A., Director of the 'Art Gallery of the Corporation of London. THOMAS HENRY ELLIS, E sq., D eputy , Chairman. 1907. 3ntrobuction By A. G. T e m p l e , F.S.A, H E earliest pictures in the present collection are T those of C arl' Gustav Pilo, and Jens Juel. Painted at a time in the 1 8 th century when the prevalent and popular manner was that better known to us by the works o f the notable Frenchmen, Largillibre, Nattier, De Troy and others, these two painters caught something o f the naivété and grace which marked the productions of these men. In so clear a degree is this observed, not so much in genre, as in portraiture, that the presumption is, although it is not on record, at any rate as regards Pilo, that they must both have studied at some time in the French capital. N o other painters of note, indigenous to the soil o f Denmark, had allowed their sense of grace such freedom to so express itself. -

The Book Can Be Downloaded Here. Every Corner Was a Picture 4Th

EVERY CORNER WAS A PICTURE 165 artists of Newlyn and the Newlyn Art Colony 1880–1900 a checklist compiled by George Bednar Fourth Edition 1 2 EVERY CORNER WAS A PICTURE 165 artists of Newlyn and the Newlyn Art Colony 1880–1900 Fourth Edition a checklist compiled by George Bednar ISBN 978 1 85022 192 0 1st edition published 1999 West Cornwall Art Archive 2nd edition © Truran 2004, revised 2005 3rd edition © Truran 2009, revised 2010, 2015 4th edition © Truran 2020 Published byTruran, an imprint of Tor Mark, United Downs Ind Est, St Day, Redruth TR16 5HY Cornwall www.truranbooks.co.uk Printed and bound in Cornwall by R. Booth Ltd, The Praze, Penryn, TR10 8AA Cover image: Walter Langley The Breadwinners/Newlyn Fishwives (Penlee House Gallery & Museum) Insert photographs: © Newlyn Artists Photograph Album, 1880s, Penlee House Gallery & Museum & Cornwall Studies Centre, Redruth ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I take this opportunity to thank Heather and Ivan Corbett, as well as Yvonne Baker, Steve Baxter, Alison Bevan (Director, RWA, formerly Director, Penlee House), John Biggs, Ursula M. Box Bodilly, Cyndie Campbell (National Gallery of Canada), Michael Carver, Michael Child, Robin Bateman, Michael Ginesi, Iris M. Green, Nik Hale, Barbara B. Hall, Melissa Hardie (WCAA), James Hart, Elizabeth Harvey-Lee, Peter Haworth, Katie Herbert (Penlee House, who suggested Truran), Jonathan Holmes, Martin Hopkinson, Ric and Lucy James, Tom and Rosamund Jordan, Alice Lock, Huon Mallallieu, David and Johnathan Messum, Stephen Paisnel, Margaret Powell, M.C. Pybus, Claus Pese, Brian D. Price, Richard Pryke, John Robertson, Frank Ruhrmund, Denise Sage, Peter Shaw, Alan Shears, Brian Stewart, David and Els Strandberg, Leon Suddaby, Sue and Geoffrey Suthers, Peter Symons, Barbara Thompson, David Tovey, Archie Trevillion, Ian Walker, Peter Waverly, John and Denys Wilcox, Christopher Wood, Laura Wortley, Nina Zborowska, and Valentine and John Foster Tonkin. -

St Mark's Parish News

St Mark’s Parish News Candlemas 2 February 2020 Church Services Thank you 2 February - Candlemas The flowers in church this week 8.30am Holy Communion are in memory of our dear friend 9.30am Morning Worship Margaret Standley. Preacher - The Reverend Dr Sam Cappleman Leadership - Mrs Janet Warren Intercessions - Young People Organist - Mr Bill Fudge Lectionary Readings Malachi 3:1-5 Hebrews 2:14-18 Luke 2:22-40 Prayer for Sunday and the Week Ahead 9 February - Candlemas 8.30am Holy Communion Lord God on this day we 9.30am Morning Worship celebrate the Light of Christ. Preacher - The Reverend Canon Charles Royden He is your light which gives Leadership - The Reverend Alan Kirk light to the whole world. Intercessions - Mr Richard Ledger Organist - Mr Paul Edwards May we to be lights of your Lectionary Readings presence here on earth. Isaiah 58:1-9a 1 Corinthians 2:1-12 Matt 5:13-20 Midweek Services In our actions and in our Wednesday Communion 10.00am in the Chapel words, help us by your Holy Spirit to reflect the Light of Please join us for a service followed by coffee First Monday of every month. Holy Communion Christ’s love and salvation. at 10.00am at Sir William Harpur House Parish News is available online at www.stmarkschurch.com You can also sign up online to receive each edition by email St Mark’s Contact Information The Reverend Dr. Sam Cappleman St. Mark’s Church Centre Assistant Rural Dean of Bedford www.stmarkschurch.com 107 Dover Crescent, Bedford MK41 Tel: 266952 [email protected] Open Monday - Friday 9am - 5.00pm Tel/fax: 342613 [email protected] The Reverend Canon Charles Royden Centre Manager: Miss Wendy Rider 342613 The Vicarage, Calder Rise. -

Bn 2017 4.Pdf

impulse & informationen inhalt 4/2017 Aktuelle Buchtipps ...........................................................................................................................595 Thema Sprechende Gesichter... von Reinhard Ehgartner..................................................................601 Ins Gesicht geschrieben ... von Nicole Malina Urbanz .......................................................................603 #CoverUP!! ... von Reinhard Ehgartner ... ..........................................................................................607 Von der Kunst, Gesichter zu fangen... von Roman Huditsch .............................................................610 Ganz ohne Hintergrund... von Fritz Popp ...........................................................................................613 Der Begriff „Gesicht“ in der Bibel ... von Hanns Sauter ......................................................................616 biblio-Filmschnitt: in Kooperation mit „Filmdienst“ - „The Double“ ......................................................620 Lesebilder : Bilderlesen - Marianne Stokes ... von Doris Schrötter ....................................................622 Buchstart Österreich : die neue Homepage .......................................................................................624 MINT : der Auftakt ...............................................................................................................................626 Allgemeine Weisheiten über Stechmücken : Gerda Gelse ... von Veronika Mayer-Miedl -

UK National Report (WP 2 - Deliverable 2.2)

UK National report (WP 2 - Deliverable 2.2) Pictures: Inshore fishing boats, Cornwall & Dairy cow, Somerset Authors: Damian MAYE, James KIRWAN, Mauro VIGANI, Dilshaad BUNDHOO and Hannah CHISWELL Organisations April 2018 H2020-SFS-2014-2 SUFISA Grant agreement 635577 1 UK National report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 12 1 Introduction and methods ........................................................................... 40 2 Media Content Analysis ............................................................................... 42 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 42 2.2 The predominance of price volatility in media discourses about UK agriculture .... 42 2.3 Inshore fisheries ...................................................................................................... 43 2.4 The dairy sector ....................................................................................................... 46 3 Brexit and the UK agri-food sector ................................................................ 50 3.1 Brexit: introduction ................................................................................................. 50 3.2 Brexit: fisheries, including inshore fisheries ............................................................ 53 3.2.1 Fisheries management ................................................................................... -

Response to Covid-19 Highlights of the Year Penzance Council Annual

PENZANCE TOWN COUNCIL Annual Report 2019/2020 Penzance Council Annual Report 2019/2020 Response to Covid-19 Our staff teams have continued to work throughout the Over £18,000 was paid out to organisations including: Coronavrius pandemic to keep Council operations and • St Petrocs services running for our residents. • Whole Again Communities Unfortunately, many events had to be cancelled or • Growing Links postponed due the virus but we were able to act • Pengarth Day Centre quickly to support local initiatives that were set up to • Solomon Browne Memorial Hall help everyone during the lockdown. • The Fisherman’s Mission In March, we mobilised our Social Action Fund to start • West Cornwall Women’s Aid making grant payments to local organisations, and • iSight Cornwall groups helping our community, as part of a package of support to help everyone get through the crisis. We also worked closely with Cornwall Council to provide support to the vulnerable members of our community. Highlights of the Year Climate emergency strategy We are very proud to be one of the first local councils Tackling anti-social behaviour in the country to adopt a Climate Emergency Plan. We We took decisive action to secure the future of our are committed to leading the fight against climate Anti-Social Behaviour case worker after Cornwall change in Penzance and are looking forward to Council reported that it was unable to continue to working with our partners, local residents and visitors provide the same level of funding for the post. This to deliver our ambitious plans. would have led to the case worker reverting to cover Most recently, we have granted £8,500 to Sustainable the wider West Cornwall area, including Hayle, St Ives, Penzance to design an online portal and a set of Camborne, Pool and Redruth, rather than focusing Community Toolkits to help households, businesses, Penzance alone. -

Malerier Og Tegninger 1 - 126

FINE ART + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1 - 547 FINE ART + ANTIQUES International auction 872 AUCTION 30 May - 1 June 2017 PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_antik_s001-013_start.indd 1 04/05/17 18.37 Lot 66 DEADLINE FOR CLAIMING ITEMS: WEDNESDAY 21 JUNE Items bought at Auction 872 must be paid no later than eight days from the date of the invoice and claimed on Bredgade 33 by Wednesday 21 June at the latest. Otherwise, they will be moved to Bruun Rasmussen’s storage facility at Baltikavej 10 in Copenhagen at the buyer’s expense and risk. This transportation will cost DKK 150 per item VAT included, and storage will cost DKK 150 per item per week VAT included. SIDSTE FRIST FOR AFHENTNING: ONSDAG DEN 21. JUNI Effekter købt på auktion 872 skal være betalt senest 8 dage efter fakturadatoen og afhentet i Bredgade 33 senest onsdag den 21. juni. I modsat fald bliver de transporteret til Bruun Rasmussens lager på Baltikavej 10 i Københavns Nordhavn for købers regning og risiko. Transporten koster 150 kr. pr. effekt inkl. moms, og opbevaringen koster 150 kr. pr. effekt pr. påbegyndt uge inkl. moms. 872_antik_s001-013_start.indd 2 04/05/17 18.37 DAYS OF SALE ________________________________________________________ FINE ART + ANTIQUES Tuesday 30 May 4 pm Paintings -

Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 26:1

The Danish Golden Age – an Acquisitions Project That Became an Exhibition Magnus Olausson Director of Collections Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 26:1 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, © Copyright Musei di Strada Nuova, Genova Martin van Meytens’s Portrait of Johann is published with generous support from the (Fig. 4, p. 17) Michael von Grosser: The Business of Nobility Friends of the Nationalmuseum. © National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Open © Österreichisches Staatsarchiv 2020 (Fig. 2, Access image download (Fig. 5, p. 17) p. 92) Nationalmuseum collaborates with Svenska Henri Toutin’s Portrait of Anne of Austria. A © Robert Wellington, Canberra (Fig. 5, p. 95) Dagbladet, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, New Acquisition from the Infancy of Enamel © Wien Museum, Vienna, Peter Kainz (Fig. 7, Grand Hôtel Stockholm, The Wineagency and the Portraiture p. 97) Friends of the Nationalmuseum. © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam/Public Domain (Fig. 2, p. 20) Graphic Design Cover Illustration © Christies, 2018 (Fig. 3, p. 20) BIGG Daniel Seghers (1590–1661) and Erasmus © The Royal Armoury, Helena Bonnevier/ Quellinus the Younger (1607–1678), Flower CC-BY-SA (Fig. 5, p. 21) Layout Garland with the Standing Virgin and Child, c. Four 18th-Century French Draughtsmen Agneta Bervokk 1645–50. Oil on copper, 85.5 x 61.5 cm. Purchase: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Wiros Fund. Nationalmuseum, NM 7505. NY/Public Domain (Fig. 7, p. 35) Translation and Language Editing François-André Vincent and Johan Tobias Clare Barnes and Martin Naylor Publisher Sergel. On a New Acquisition – Alcibiades Being Susanna Pettersson, Director General. Taught by Socrates, 1777 Publishing © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ludvig Florén, Magnus Olausson, and Martin Editors NY/Public Domain (Fig. -

Live Wrasse Fishery in Devon and Severn IFCA District

Live Wrasse Fishery in Devon and Severn IFCA District Research Report November 2018 Sarah Curtin Dr Libby West Environment officer Senior Environment officer Version control history Author Date Comment Version Sarah Curtin 13/11/2018 Prepared for Byelaw sub-committee meeting 1 on 20 November 2018 2 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Landings Data .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. On-board Observer Surveys .................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Data Analysis ........................................................................................................................... 8 2.3.1. Total Landings ................................................................................................................. 8 2.3.2. Observer Effort ................................................................................................................ 8 2.3.3. Catch Per Unit Effort ......................................................................................................