Art Acknowledged and Disregarded: Art and Its National Context at St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

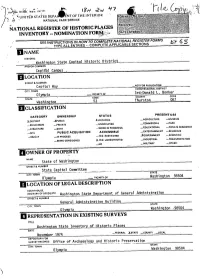

Washington State Capitol Historic District Is a Cohesive Collection of Government Structures and the Formal Grounds Surrounding Them

-v , r;', ...' ,~, 0..,. ,, FOli~i~o.1('1.300; 'REV. 19/771 . '.,' , oI'! c:::: w .: ',;' "uNiT~DSTATES DEPAANTOFTHE INTERIOR j i \~ " NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -, i NATIONAL REGISTER OF mSTORIC PLACES INVENTORY .- NOMINATION FOR~;';;" SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMP/"£J'E NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES·· COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS , " DNAME HISTORIC Washington State,CaRito1 Historic District AND/OR COMMON Capit'olCampus flLOCATION STREET &. NUMBER NOT FOR PUBUCATION Capitol Way CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 3rd-Dona1d L. Bonker Olympia ·VICINITY OF coos COUNTY CODE STATE 067 Washington 53 Thurston DCLASSIFICA TION PRESENT USE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS _MUSEUM x..OCCUPIED -AGRICULTURE .x..OISTRICT ..xPUBLIC __ COMMERCIAL _PARK _SUILDINGISI _PRIVATE _UNOCCUPIED _EDUCATIONAL _PRIVATE RESIDENCE _STRUCTURE _BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _ENTERTAINMENT _REUGIOUS _SITe , PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -XGOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC _OBJ~CT _IN PRoCesS __VES:RESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL _TRANSPORTATION _BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED _NO -MIUTARY _OTHER: NAME State of Washington STREET &. NUMBER ---:=-c==' s.tateCapitol C~~~~.te~. .,., STATE. CITY. TOWN Washington 98504 Olympia VICINITY OF ElLGCA TION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEOS.ETC. Washin9ton State Department of General Administration STREET & NUMBER ____~~~--------~G~e~n~e~ra~l Administration Building STATE CITY. TOWN 01ympia Washington -9B504 IIREPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS' trTlE Washington State Invent~,r~y~o~f_H~l~'s~t~o~r~ic~P~l~~~ce~s~----------------------- DATE November 1974 _FEOERAL .J(STATE _COUNTY ,-lOCAL CITY. TOWN Olympia ' .. I: , • ", ,j , " . , . '-, " '~ BDESCRIPTION CONOITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE 2lexcElLENT _DETERIORATED ..xUNALTERED .xORIGINAl SITE _GOOD _ RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE _ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ------====:: ...'-'--,. DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL IIF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Washington State Capitol Historic District is a cohesive collection of government structures and the formal grounds surrounding them. -

AVAILABLE from Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 853 SO 029 147 TITLE Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher Resource Guide. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 71p. AVAILABLE FROM Arizona State Department of Library, Archives, and Public Records--Museum Division, 1700 W. Washington, Phoenix, AZ 85007. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; Field Trips; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Local History; *Museums; Social Studies; *State History IDENTIFIERS *Arizona (Phoenix); State Capitals ABSTRACT Information about Arizona's history, government, and state capitol is organized into two sections. The first section presents atimeline of Arizona history from the prehistoric era to 1992. Brief descriptions of the state's entrance into the Union and the city of Phoenix as theselection for the State Capitol are discussed. Details are given about the actualsite of the State Capitol and the building itself. The second section analyzes the government of Arizona by giving an explanation of the executive branch, a list of Arizona state governors, and descriptions of the functions of its legislative and judicial branches of government. Both sections include illustrations or maps and reproducible student quizzes with answer sheets. Student activity worksheets and a bibliography are provided. Although designed to accompany student field trips to the Arizona State Capitol Museum, the resource guide and activities -

David a Lester and the Kinsley Civil War Monument

Civil War Valor in Concrete by Randall M. Thies emorial Day, 1917: David Lester looked on with pride as the recently completed Civil War monument was unveiled in Hillside Cemetery, a short Mdistance northwest of Kinsley, Kansas. A Union vet- eran and longtime resident of the Kinsley area, Lester had a special reason to be proud of the new monu- ment: he was the artist who had created it. Memorial Day was always a special occasion, but the unveiling of the new monument made this day even more so, attracting a large crowd despite threat- ening weather and bad roads. After beginning the day with a band concert, speeches, and parade in downtown Kinsley, the crowd gathered at the ceme- tery to share in the dedication of its new monument. Uniformed members of the Knights of Pythias served as a ceremonial firing squad, while flower girls in white dresses provided a festive air. Honored as the The Kinsley Civil War monument photographed about the time of its dedication—Memorial Day, 1917. Randall W. Thies is an archeologist and cultural resource specialist with the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka and currently serves as state coor- dinator for the Kansas Save Outdoor Sculpture! (SOS!) project. A graduate of Washburn University, he received an M.A. in sociology (anthropology) from Iowa State University in 1979. 164 KANSAS HISTORY David A. Lester and the Kinsley Civil War Monument creator of the monument, David Lester also read the memorial service, as appropriate to his role as com- mander of Kinsley’s Timothy O. Howe Post 241 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a nationwide Union veterans organization. -

Sculptor Charles Adrian Pillars

CHARLES ADRIAN PILLARS (1870-1937), JACKSONVILLE‟S MOST NOTED SCULPTOR By DIANNE CRUM DAWOOD A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Dianne Crum Dawood 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to acknowledge my thesis chair, Dr. Melissa Hyde, and committee members, Dr. Eric Segal and Dr. Victoria Rovine, for serving on this project for me. Their suggestions, insightful analysis, encouragement, and confidence in my candidacy for a master‟s in art history were important support. I also enjoyed their friendship and patience during this process. The wordsmithing and editing guidance of Mary McClurkin was a delightful collaboration that culminated in a timely finished paper and a treasured friendship. Assistance from Deanne and Ira in the search of microfilm and microfiche records turned a project of anticipated drudgery into a treasure hunt of exciting finds. I also appreciated the suggestions and continued interest of Dr. Wayne Wood, who assured me that Charles Adrian Pillars‟s story was worthy of serious research that culminated in learning details of his life and career heretofore unknown outside of Pillars‟s family. Interviews with Pillars‟s daughter, Ann Pillars Durham, were engaging time travels recalling her father and his celebrity and the family‟s economic and personal vicissitudes during the Great Depression. She also graciously allowed me to review her personal papers. Wells & Drew, the parent company of which was founded in Jacksonville in 1855, permitted my use of a color image, and The Florida Times-Union granted permission to use some of their photographs in this paper. -

Washington State Veterans and Law Enforcement Memorials

Washington State Veterans and Law Enforcement Memorials Winged Victory POW/MIA Medal of Honor Memorial Memorial Memorial Law Enforcement Memorial Korean War Vietnam World War II Veterans Memorial Veterans Memorial Memorial WINGED VICTORY completion. The sculpture took seven years WORLD WAR I to complete. Winged Victory is distinctive as the first In a solemn and patriotic ceremony on and only work of public art to be carefully the capitol grounds May 30, 1938, Winged integrated into the original composition of Victory was dedicated to recognize and the landscape and buildings of the capitol remember the service of World War I veter- campus. The bronze sculpture features a ans. The sculpture was unveiled by two Gold 12-foot tall figure of Nike, the Greek god- Star mothers, Mrs. Charles V. Leach and dess of Victory, standing protectively behind Mrs. Cordelia Cater, after whose sons the highly detailed figures of a soldier, a sailor, a Olympia posts of the American Legion and marine, and a Red Cross nurse. The bronze the Veterans of Foreign Wars were named. sculpture received major conservation work The monument was authorized by the State and full restoration in 2008. Legislature in 1919, along with funding Winged Victory is situated just north of the for a new capitol building. Soon busy with Insurance Building. construction of the new capitol however, the Legislature did not formally commis- sion Northwest sculptor Alonzo Victor Lewis until 1931, as the new capitol reached PAOW/MI MEMORIAL was originally created as a Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1982. When the more extensive A memorial to American prisoners of war Vietnam Memorial was dedicated, the origi- and those missing in action was dedicated nal marker was refitted with a new granite in a solemn ceremony on September 16, top and inscribed with words honoring 1988. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

! Form No. 10-300 REV. <9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Washington State Capitol Historic District AND/OR COMMON Capitol Campus LOCATION STREET& NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Olympia ___.VICINITY OF 3rd-Donald L. Bonker STATE CODE COUNTY CODEi Washington 53 Thurston 067 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE XDISTRICT _XPUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED JSGOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO ... —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME State of Washington STREET & NUMBER State Capitol Committee CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia VICINITY OF Washington 98504 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs,ETc. Washington State Department of General Administration STREET & NUMBER General Administration Building CITY, TOWN STATE Olympia Washington 98504 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS fPTLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE November 1974 —FEDERAL JCSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Office of Archaeol ogy and Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE Qlympia Washington 98504 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE 4-EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED JS.UNALTERED _XORIGINALSITE _GOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Washington State Capitol Historic District is a cohesive collection of government structures and the formal grounds surrounding them. Located in Olympia, the state capitol, the district's main building is the most prominent architectural feature of the city and is visible for several miles. -

Searchablehistory.Com 1930-1939 P. 1 DEPRESSION YEARS

DEPRESSION YEARS CHANGES LIVES Survival in the Pacific Northwest was difficult at the beginning of the 1930s economic realities of falling farm prices, industrial unemployment and foreclosed mortgages all added up to pervasive despair ironically, this reality followed the most prosperous decade in regional history to date AGRICULTURE WAS HARD HIT BY DEPRESSION Farming was in the doldrums with the collapse of the world economy although farming remained an important source of employment in Washington state farm population during the 1930s dropped to 20% of its former number Farm life changed during the Great Depression income was down which meant many farmers were forced to sell out to more fortunate neighbors number of farms shrank as the economic depression eliminated markets for farm goods percentage of tenants renting farms increased dramatically Drought added to the misery factor as crops burned in the fields in Eastern Washington banks foreclosed on farms -- farmers moved into cities tax-delinquency added land to state’s public trust lands Soil erosion was a most serious long-term problem for farmers and tenants alike one quarter of the cropland of the Northwest was badly damages by erosion in the cattle industry overgrazing destroyed vegetation and soil alike But farmers who could hold on were able to increase the size of their holdings wheat, hay and oats were the principal products with fruits and nuts rising in importance GREAT DEPRESSON EXPANDS THE DEMAND FOR THE PIKE PLACE MARKET Several multi-level buildings were constructed -

![Capitol Campus Click the Layers Button [ ] on Your Acrobat Reader for Additional Views (Points of Interest, Parking, Bus Stop, Etc.)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6967/capitol-campus-click-the-layers-button-on-your-acrobat-reader-for-additional-views-points-of-interest-parking-bus-stop-etc-4216967.webp)

Capitol Campus Click the Layers Button [ ] on Your Acrobat Reader for Additional Views (Points of Interest, Parking, Bus Stop, Etc.)

8th Ave SE Capitol Lake Park Washington State Capitol Campus Click the Layers button [ ] on your Acrobat Reader for additional views (points of interest, parking, bus stop, etc.) Government building Visitor Parking - $1.50 per hour 9th Ave SE N Intercity Transit Entrance Parking Free shuttle Point of interest Adams St. SE Franklin St. SE Oct. 2011 10th Ave SE Washington St. SE Capitol Way S Columbia St SW Capitol Lake Union Ave SE Union Ave SE SUVs, Vans, Centennial Park Trucks General restricted State Farm Administration 11th Ave SE Plum St. SE Capitol Park Capitol ProArts SE St. Jeerson 11th Ave SE WWII Memorial Capitol Conservatory 12th Ave SE W Court Capitol S Law Enforcement Memorial t Water S Natural Resources Sunken Temple of Justice Garden North Diagonal Chestnut St. SE Cherry Ln. SW Highways Licenses 13th Ave SE Cherry St. SE d Vict Archives State ge or in y Medal of Honor W Woman POW/MIA Dancing Tivoli Fountain Oce Building 2 South Diagonal 14th Ave SE SE Blvd. Henderson Insurance Vietnam Veteran Memorial East Plaza Garage (below) Legislative Building 14th Ave SE 14th Ave SE Capitol Gateway Park Sid Snyder Ave SW Untitled Governnor’s Visitor Center Stainless Steel Mansion Korean War Boiler Pedestrian Bridge Memorial Works O’Brien Sundial Cherberg Press houses Water Garden Newhouse The 15th Ave SW Transportation Shaman Mysteries 1500 Jeerson 15th Ave SW of Life Capitol Way Capitol Way S Columbia St SW St Columbia Pritchard SW St. Water Modular Oces DES 14th Ave SE A-G Employment IBM Security Sylvester St. -

INSTRUMENT of SURRENDER We, Acting by Command of and in Behalf

INSTRUMENT OF SURRENDER We, acting by command of and in behalf of the Emperor of Japan, the Japanese Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters, hereby accept the provisions set forth in the declaration issued by the heads of the Governments of the United States, China, and Great Britain on 26 July 1945 at Potsdam, and subsequently adhered to by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which four powers are hereafter referred to as the Allied Powers. We hereby proclaim the unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers of the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters and of all Japanese armed forces and all armed forces under the Japanese control wherever situated. We hereby command all Japanese forces wherever situated and the Japanese people to cease hostilities forthwith, to preserve and save from damage all ships, aircraft, and military and civil property and to comply with all requirements which my be imposed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers or by agencies of the Japanese Government at his direction. We hereby command the Japanese Imperial Headquarters to issue at once orders to the Commanders of all Japanese forces and all forces under Japanese control wherever situated to surrender unconditionally themselves and all forces under their control. We hereby command all civil, military and naval officials to obey and enforce all proclamations, and orders and directives deemed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to be proper to effectuate this surrender and issued by him or under his authority and we direct all such officials to remain at their posts and to continue to perform their non-combatant duties unless specifically relieved by him or under his authority. -

Washington State Capitol Campus

Heritage Park 8th Ave SE Washington State Capitol Campus Government building $ Visitor Parking - $2 per hour P (requires exact change) Intercity Transit Entrance Parking 9th Ave SE Free shuttle Point of interest Bike rack Civic Education Tour Bus Parking A dams S F Guard Stations Electric Vehicle Parking r anklin S 10th Ave SE W ashingt t C . SE Jan. 2020 apit C Parkin S Reserve olumbia S tate Employe t . SE ol on S W g d a y S t . SE ve SE d t SW Union A o o h e te ta S f Capitol Lake o rc N A Union Ave SE 18 Centennial Park $ General Helen Sommers State Farm P Administration 11th Ave SE Building Plum S ProArts t . SE 11th Ave SE WWII Memorial 10 t r ou 1 C Capitol $ e SE ol 12th Av Conservatory t P 2 api W $ C S Law Enforcement Memorial t P Water S Natural Resources iagonal Sunken es th D v Temple of Justice Garden Nor chi r C A hestnut S C e ve SE t 13th A h Highways Licenses C a e t herr V S r ed icto r g r in y 4 y Medal of Honor 11 W L Woman y S n Dancing t . SE . POW/MIA t S 5 . SE W 3 Tivoli Fountain 6 South D e c iagonal H B an ve SE enderson r 14th A $ Insu Vietnam Veteran Memorial P East Plaza Garage (below) Capitol Gateway Park Legislative Building 7 v l 14th A d 14th Ave SE ve SE SE . -

Halprin Report 10-04FINAL.Pub

Water Garden Lawrence Halprin and the East Capitol Campus A report by the Washington State Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and the Washington State Arts Commission Commissioned by the Department of General Administration Division of Facilities Planning and Management October 2004 Water Garden: Lawrence Halprin and the East Capitol Campus Page 1 Page 2 Water Garden: Lawrence Halprin and the East Capitol Campus Lawrence Halprin and the East Capitol Campus A report by the Washington State Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and the Washington State Arts Commission Commissioned by the Department of General Administration Division of Facilities Planning and Management October, 2004 Water Garden, 1972 Photo courtesy the Office of Lawrence Halprin Executive Summary: Findings and Recommendations This report provides information to assist in an evaluative analysis of the Water Garden, a sculptural fountain created in 1972 for the East Capitol Campus in Olympia, Washington. In- cluded is the history of the fountain's creation, background on the designer, Lawrence Halprin, an examination of the artistic context in which the fountain was created, comparison with other Halprin fountains in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere in the United States, and recommen- dations for the preservation and restoration of the fountain on the East Capitol Campus. Lawrence Halprin is recognized as one of the outstanding landscape architects of our time. He has created a broad range of fountains, landscapes and urban designs throughout the United Water Garden: Lawrence Halprin and the East Capitol Campus Page 3 States and abroad. He is one of only two land- scape architects to be honored by the President of the United States for "outstanding contribu- tions to the excellence, growth, support and availability of the arts in the United States." Water Garden should be viewed not only as a sculptural element of the State Capitol Campus, but also for its significance within the larger scope of Halprin work within Washington State.