Homage to Poulenc by Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

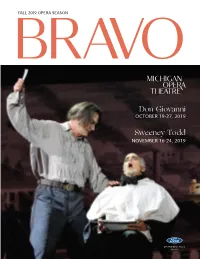

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Piers Lane Biography

Piers Lane Biography “… No praise could be high enough for Piers Lane whose playing throughout is of a superb musical intelligence, sensitivity, and scintillating brilliance…” (Bryce Morrison, Gramophone) London-based Australian pianist Piers Lane has a flourishing international career, which has taken him to more than forty countries. Highlights of the past few years have included a sold-out performance with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Alexander Verdernikov at London’s Royal Festival Hall, concerto performances at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, a three-recital series entitled Metamorphoses and other performances for the London Pianoforte series at Wigmore Hall and five concerts for the opening of the Recital Centre in Melbourne. Five times soloist at the BBC Proms in London’s Royal Albert Hall, Piers Lane’s wide-ranging concerto repertoire exceeds eighty works and has led to engagements with many of the world’s great orchestras including the BBC and ABC orchestras; the Aarhus, American, Bournemouth and Gothenburg Symphony Orchestras; the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Kanazawa Ensemble, Orchestre National de France, City of London Sinfonia, and the Royal Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and Warsaw Philharmonic orchestras among others. Leading conductors with whom he has worked include Andrey Boreyko, Sir Andrew Davis, Richard Hickox, Andrew Litton, Sir Charles Mackerras, Jerzy Maxymiuk, Maxim Shostakovich, Vassily Sinaisky, Yan Pascal Tortelier and Antoni Wit. His 2007 performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with the Queensland Symphony Orchestra and Pietari Inkinen received the Limelight Magazine Award for Best Orchestral Performance in Australia. 1 Festival appearances have included, among others, Aldeburgh, Bard, Bergen, Cheltenham, Como Autumn Music, Consonances , La Roque d’Anthéron, Newport, Prague Spring, Ruhr Klavierfestival, Schloss vor Husum and the Chopin festivals in Warsaw, Duszniki- Zdroj, Mallorca and Paris. -

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

La Voix Humaine: a Technology Time Warp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp Whitney Myers University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.332 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Myers, Whitney, "La Voix humaine: A Technology Time Warp" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/70 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Beethoven: Symphony No 9 “Choral” – Australian World Orchestra Posted on April 16, 2014 by Barry Walmsley

Beethoven: Symphony No 9 “Choral” – Australian World Orchestra Posted on April 16, 2014 by Barry Walmsley Australian World Orchestra Sydney Philharmonia Choir Conductor: Alexander Briger ABC 481 0550 The scale of a work such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is truly staggering. Whilst the work has been overused for civic celebratory events, the concert experience (and this recording, which originates from a live concert in the Sydney Opera House) is something that can touch listeners in profound ways. The complexity of the music is only equalled by its challenging compositional ideas, along with the treatment of text (by Schiller), and the fusion of what, for the most part, are incompatibles, that is, the choral and the symphonic idiom. Structurally, the work is really a set of variations, showing a total connection from beginning to end. These totally new elements (the unconventional symphonic layout and the use of words within a symphony) helped to underline, in the public’s mind, that Beethoven had truly gone mad. This particular recording emanated from one of the most exciting of recent concert events, the inaugural season by the newly created Australian World Orchestra, an initiative to bring together the finest of Australian orchestral musicians from around the country and across the world. Thus, it saw players return from such illustrious orchestras as the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics, Chicago and London Symphonies, the Concertgebouw and Gewandhaus, to be part of this concept orchestra. Bringing the whole project together, as its artistic and musical director, was conductor Alexander Briger, who has established himself on the world stage as one of the new dynamic conductors of this era. -

Francis Poulenc and Surrealism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Master of Humanities Capstone Projects Master of Humanities Program 1-2-2019 Francis Poulenc and Surrealism Ginger Minneman Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/humanities Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Minneman, G. (2019) Francis Poulenc and Surrealism. Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Humanities Program at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Humanities Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minneman 1 Ginger Minneman Final Project Essay MA in Humanities candidate Francis Poulenc and Surrealism I. Introduction While it is true that surrealism was first and foremost a literary movement with strong ties to the world of art, and not usually applied to musicians, I believe the composer Francis Poulenc was so strongly influenced by this movement, that he could be considered a surrealist, in the same way that Debussy is regarded as an impressionist and Schönberg an expressionist; especially given that the artistic movement in the other two cases is a loose fit at best and does not apply to the entirety of their output. In this essay, which served as the basis for my lecture recital, I will examine some of the basic ideals of surrealism and show how Francis Poulenc embodies and embraces surrealist ideals in his persona, his music, his choice of texts and his compositional methods, or lack thereof. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

Jackie Aprile Jr

Jackie Aprile Jr. Jackie Aprile Jr. - Amour Fou (2001) Jackie Aprile Jr. - Pine Barrens (2001) Jackie Aprile Jr. - To Save Us All from Satan's Power (2001) Jackie Aprile Jr. - The Telltale Moozadell (2001) Jackie Aprile Jr. Show all 12 episodes. 1989 Collision Course (uncredited). 1988 Spike of Bensonhurst Gang Member. 1987 Suzanne Vega: Luka (Video short) Luka. Hide Show Self (1 credit). 2009 Waiting for Giacomo Michael "Jackie" Aprile Jr. (1977-2001) was an associate of Ralph Cifaretto's crew in the DiMeo crime family. In 2001, he was whacked by Vito Spatafore for robbing Eugene Pontecorvo's card game. Giacomo Michael Aprile Jr. was born in Newark, New Jersey in 1977, the son of Jackie Aprile Sr. and the nephew of Richie Aprile. He was kept away from the family business by his father, but his father's death and the release of his uncle from prison in 2000 led to Jackie becoming involved with the Jackie Aprile, Jr. and his friend Dino Zerilli want to get ahead in life and become more than mere associates. ⦠Kelli attended the funeral of her brother, Jackie Aprile, Jr. and suggested that the mafia was responsible for his death. Meadow Soprano chastised her for speaking of their family connections in front of an outsider and suggested that Kelli lacked loyalty. ⦠Christopher is left outside with fellow soldier Vito Spatafore while the senior family members have their discussion. Template:Character infobox 2 yes. "My Father ". ╠Jackie Aprile, Jr. Giacomo Michael Aprile, Jr. (commonly referred to as Jackie, Jr. ), played by Jason Cerbone , is a fictional character on the HBO TV series The Sopranos . -

Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 by Sergey Prokofiev

SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors ColLege by Danielle Emily Stevens San Marcos, Texas May 2014 1 SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Kay Lipton, Ph.D. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Adah Toland Jones, D. A. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Cynthia GonzaLes, Ph.D. School of Music Approved: ____________________________________ Heather C. GaLLoway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors ColLege 2 Abstract This thesis contains a performance guide for Sergey Prokofiev’s Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 (1943). Prokofiev is among the most important Russian composers of the twentieth century. Recognized as a leading Neoclassicist, his bold innovations in harmony and his new palette of tone colors enliven the classical structures he embraced. This is especially evident in this flute sonata, which provides a microcosm of Prokofiev’s compositional style and highlights the beauty and virtuosic breadth of the flute in new ways. In Part 1 I have constructed an historical context for the sonata, with biographical information about Prokofiev, which includes anecdotes about his personality and behavior, and a discussion of the sonata’s commission and subsequent premiere. In Part 2 I offer an anaLysis of the piece with generaL performance suggestions and specific performance practice options for flutists that will assist them as they work toward an effective performance, one that is based on both the historically informed performance context, as well as remarks that focus on particular techniques, challenges and possible performance solutions. -

Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM and CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI and EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available Via Online Streaming Anytime

OPERA SAN JOSÉ EXTENDS ACCESS TO VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE OF Jake Heggie’s “Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM AND CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI AND EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available via online streaming anytime SAN JOSE, CA (3 February 2021) – In keeping with Opera San José’s mission to expand accessibility to its work, the company has announced that through the support of generous donors it is able to extend access to its hit virtual production of Jake Heggie’s chamber opera, Three Decembers, now making it available on a pay-what-you-can basis for streaming on demand. The production is being offered with subtitles in Spanish and Vietnamese, as well as English, furthering its accessibility to the Spanish and Vietnamese speaking members of the San Jose community, two of the largest populations in its home region. Featuring world-renowned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham in the central role, alongside celebrated Opera San José Resident Artists soprano Maya Kherani and baritone Efraín Solís, this world-class digital production has been met with widespread critical acclaim. Based on an unpublished play by Tony Award winning playwright Terrence McNally, Three Decembers follows the riveting story of a famous stage actress and her two adult children, struggling to connect over three decades, as long-held secrets come to light. With a brilliant, witty libretto by Gene Scheer and a soaring musical score by Jake Heggie, Three Decembers offers a 90-minute fullhearted American opera about family – the ones we are born into and those we create. Tickets for the modern work, which was recorded last Fall in the company’s Heiman Digital Media Studio, are pay-what-you-can beginning at $15 per household, which includes on-demand streaming for 30 days after date of purchase. -

Francis Poulenc

CORO CORO Palestrina – Volume 6 “Christophers artfully moulds and heightens the contours of the polyphonic lines, which ebb and flow in a liquid tapestry of sound...[The Sixteen] are ardent and energetic in ‘Surge amica mea’, radiant in ‘Surgam et circuibo FRANCIS POULENC civitatem’, painting and animating the words to vibrant effect.” ***** Performance ***** Recording Mass in G BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE cor16133 Choral & Song Choice October 2015 Un soir de neige James MacMillan: Litanies à la Vierge Noire Stabat Mater Edmund Rubbra “A masterpiece.” “Harry Christophers balances Quatre motets pour artsdesk the soaring soprano of Julie le temps de Noël Cooper caressingly against the ensemble singers, in a “A haunting and Quatre motets pour powerful new performance which achieves choral work.” ecstasy without any element un temps de pénitence of overstatement.” guardian cor16150 cor16144 bbc music magazine To find out more about The Sixteen, concert tours, and to buy CDs visit The Sixteen www.thesixteen.com cor16149 HARRY CHRISTOPHERS oulenc is a composer who has fascinated me Whilst the death of his friend Ferroud had a devastating impact on Poulenc, the poetry Pever since I was a schoolboy struggling with the of Paul Éluard gave him inspiration beyond measure. Poulenc grew up with him and technical difficulties of his clarinet sonata. His music once said that ‘Éluard was my true brother – through him I learned to express the most always bears a human face and he himself felt he put his secret part of myself’. They both felt the savagery of WWII deeply, the social anguish, best and most authentic side into his choral music; the internal conflict and ignominy of the Nazi occupation.