Sculptor Charles Adrian Pillars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arts & Letters of Rocky Neck in the 1950S

GLOUCESTER, MASSACHUSETTS TheArts & Letters of Rocky Neck in the 1950s by Martha Oaks have received the attention they deserve. Four Winds: The Arts & Letters of Rocky With this exhibition, Four Winds, the Cape Neck in the 1950s is on view through Sep- ocky Neck holds the distinction as Ann Museum casts the spotlight on one of tember 29, 2013, at the Cape Ann Mu- R one of the most important places in those interludes: the decade and a half fol- seum, 27 Pleasant Street, Gloucester, American art history. Since the mid-nine- lowing the Second World War. Not so far Massachusetts, 01930, 978-283-0455, teeth century, its name has been associated in the past that it cannot be recollected by www.capeannmuseum.org. A 52-page soft with many of this country’s best known many, yet just far enough that it is apt to cover catalogue accompanies the exhibition. artists: Winslow Homer, Frank Duveneck, be lost, the late 1940s and 1950s found a All illustrated works are from the Cape Theresa Bernstein, Jane Peterson and Ed- young and vibrant group of artists working Ann Museum unless otherwise noted. ward Hopper. From the mid-1800s on the Neck. through the first quarter of the twentieth Although it is one of Cape Ann’s painter William Morris Hunt and his pro- century, the heyday of the art colony on longest-lived and best known art colonies, tégé, Helen Mary Knowlton. Hunt was Rocky Neck, the neighborhood was awash Rocky Neck was not the first. One of the one of the first art teachers to welcome with artists. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

JACKSONVILLE ENING! ffashionashion sshowshows OP aandnd vvintageintage sswapswaps eentertainingntertaining u nnewspaperewspaper free weekly guide to entertainment and more | september 28-october 4, 2006 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 september 28-october 4, 2006 | entertaining u newspaper on the cover: photo by Carlos Hooper | model Jane Gilcrease | table of contents clothes by Laura Ryan feature Pump It Up ...................................................................................... PAGE 17 Fresh Fashion at Cafe 11 ................................................................. PAGE 18 Up and Cummers Fashion Show ...................................................... PAGE 19 movies The Guardian (movie review) ............................................................. PAGE 6 Movies In Theatres This Week ....................................................PAGES 6-10 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted ............................................................ PAGE 7 School For Scoundrels (movie review) ............................................... PAGE 8 Fearless (movie review)..................................................................... PAGE 9 Open Season (movie review) ........................................................... PAGE 10 at home Kinky Boots (DVD review) ............................................................... PAGE 12 Studio 60 On The Sunset Strip (TV review) ...................................... PAGE 13 Men In Trees (TV review) ................................................................. PAGE -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Community Redevelopment Area Plans

February 2015 Community Redevelopment Area Plans Northbank Downtown CRA & Southside CRA Downtown Jacksonville Community Redevelopment Plan July 30, 2014 Acknowledgements This Community Redevelopment Plan has been prepared under the direction of the City of Jacksonville Downtown Investment Authority serving in their capacity as the Community Redevelopment Agency established by City of Jacksonville Ordinance 2012-364-E. The planning effort was accomplished through considerable assistance and cooperation of the Authority’s Chief Executive Officer, the Governing Board of the Downtown Investment Authority and its Redevelopment Plan Committee, along with Downtown Vision, Inc. the City’s Office of Economic Development and the Planning and Development Department. The Plan has been prepared in accordance with the Community Redevelopment Act of 1969, Chapter 163, Part III, Florida Statutes. In addition to those listed below, we are grateful to the hundreds of citizens who contributed their time, energy, and passion toward this update of Downtown Jacksonville’s community redevelopment plans. Mayor of Jacksonville Jacksonville City Council Alvin Brown Clay Yarborough, President Gregory Anderson, Vice-President Downtown Investment Authority William Bishop, AIA, District 2 Oliver Barakat, Chair Richard Clark, District 3 Jack Meeks, Vice-Chair Donald Redman, District 4 Craig Gibbs, Secretary Lori Boyer, District 5 Antonio Allegretti Matthew Schellenberg, District 6 Jim Bailey, Jr. Dr. Johnny Gaffney, District 7 Melody Bishop, AIA Denise Lee, District -

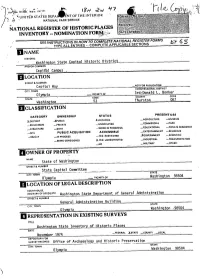

Washington State Capitol Historic District Is a Cohesive Collection of Government Structures and the Formal Grounds Surrounding Them

-v , r;', ...' ,~, 0..,. ,, FOli~i~o.1('1.300; 'REV. 19/771 . '.,' , oI'! c:::: w .: ',;' "uNiT~DSTATES DEPAANTOFTHE INTERIOR j i \~ " NATIONAL PARK SERVICE -, i NATIONAL REGISTER OF mSTORIC PLACES INVENTORY .- NOMINATION FOR~;';;" SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMP/"£J'E NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES·· COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS , " DNAME HISTORIC Washington State,CaRito1 Historic District AND/OR COMMON Capit'olCampus flLOCATION STREET &. NUMBER NOT FOR PUBUCATION Capitol Way CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 3rd-Dona1d L. Bonker Olympia ·VICINITY OF coos COUNTY CODE STATE 067 Washington 53 Thurston DCLASSIFICA TION PRESENT USE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS _MUSEUM x..OCCUPIED -AGRICULTURE .x..OISTRICT ..xPUBLIC __ COMMERCIAL _PARK _SUILDINGISI _PRIVATE _UNOCCUPIED _EDUCATIONAL _PRIVATE RESIDENCE _STRUCTURE _BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _ENTERTAINMENT _REUGIOUS _SITe , PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -XGOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC _OBJ~CT _IN PRoCesS __VES:RESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL _TRANSPORTATION _BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED _NO -MIUTARY _OTHER: NAME State of Washington STREET &. NUMBER ---:=-c==' s.tateCapitol C~~~~.te~. .,., STATE. CITY. TOWN Washington 98504 Olympia VICINITY OF ElLGCA TION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEOS.ETC. Washin9ton State Department of General Administration STREET & NUMBER ____~~~--------~G~e~n~e~ra~l Administration Building STATE CITY. TOWN 01ympia Washington -9B504 IIREPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS' trTlE Washington State Invent~,r~y~o~f_H~l~'s~t~o~r~ic~P~l~~~ce~s~----------------------- DATE November 1974 _FEOERAL .J(STATE _COUNTY ,-lOCAL CITY. TOWN Olympia ' .. I: , • ", ,j , " . , . '-, " '~ BDESCRIPTION CONOITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE 2lexcElLENT _DETERIORATED ..xUNALTERED .xORIGINAl SITE _GOOD _ RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE _ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ------====:: ...'-'--,. DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL IIF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Washington State Capitol Historic District is a cohesive collection of government structures and the formal grounds surrounding them. -

REPRODUCTION in AGE of the MECHANICAL WORK of ART Kevin Fellingham

Thresholds 16 REPRODUCTION IN AGE OF THE MECHANICAL WORK OF ART Kevin Fellingham This is not really about speed. It is rather about touch. A slow and gentle touch may be called a caress, if at high speed and with great force, an impact. Speed and force. Perhaps we could say it is about velocity It may also be about the promiscuity of ideas. If Hannah Arendt is to be believed, then Walter Benjamin desired to produce "a work consisting entirely of quotations, one that was mounted so masterfully that it could dispense with any accompanying text, "which" may strike one as whimsical in the extreme and self-destructive to boot, but it was not, any more than were the contemporaneous surrealistic experiments which arose from similar impulses. To the extent that an accom- panying text by the author proved unavoidable, it was a matter of fashioning it in such a way as to preserve" the intention of such Investigations," namely " to plumb the depths of language and thought... by drilling rather than excavating"(briefe1, 3291, so as not to ruin everything with explanations that seek to provide a causal or systematic connection." While this piece is largely a concatenation of quotes, orchestrating a colli- sion between ideas, some of which may glance off the surface of one another, others which may penetrate one another a little more deeply. The Lives of the Artists BALLARD, J.G. HAMILTON. RICHARD in full JAMES GRAHAM BALLARD (J). Nov. 15, 1930. Shanghai. China), Cb. 1922, London, Eng) English artisL may or may not have fathered pop. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A PEOPLE^S AIR FORCE: AIR POWER AND AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE, 1945 -1965 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Charles Call, M.A, M S. -

2019 STAAR Grade 6 Reading Rationales Item# Rationale

2019 STAAR Grade 6 Reading Rationales Item# Rationale 1 Option C is correct A simile is a figure of speech in which two objects are compared using the word “like” or “as.” In line 14, the author contrasts Zach’s normal behavior—“as active as a fly in a doughnut shop”—with his current behavior—“on his stomach sleeping quietly.” The simile is included to help the reader understand how much energy Zach typically has. Option A is incorrect Although the author does contrast Zach sleeping with his normal, active behavior, this is not meant to suggest that Zach has trouble falling asleep. Option B is incorrect The author compares Zach to “a fly in a doughnut shop” to emphasize how much energy Zach typically has; Zach did not actually eat any doughnuts. Option D is incorrect In paragraph 14, the author describes Michelle waking up “earlier than usual” and then taking a picture of her younger brother, so there is no evidence that Zach is sleeping late. 2 Option F is correct The theme of the story is that recognizing an unexpected opportunity can have surprising results. Throughout the story, Michelle is trying to capture the perfect picture of a sunset for the photo contest she has entered. However, she unexpectedly loves the photograph she takes of her sleeping brother and ends up submitting it for the contest. Option G is incorrect Michelle clearly enjoys taking photographs, but she is also interested in winning the photography contest, so this is not the story’s theme. Option H is incorrect Michelle is kind and patient toward her younger brother Zach, but the siblings’ relationship is not a central focus of the story and not significant to the theme. -

AVAILABLE from Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 853 SO 029 147 TITLE Arizona State Capitol Museum. Teacher Resource Guide. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 71p. AVAILABLE FROM Arizona State Department of Library, Archives, and Public Records--Museum Division, 1700 W. Washington, Phoenix, AZ 85007. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; Field Trips; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Local History; *Museums; Social Studies; *State History IDENTIFIERS *Arizona (Phoenix); State Capitals ABSTRACT Information about Arizona's history, government, and state capitol is organized into two sections. The first section presents atimeline of Arizona history from the prehistoric era to 1992. Brief descriptions of the state's entrance into the Union and the city of Phoenix as theselection for the State Capitol are discussed. Details are given about the actualsite of the State Capitol and the building itself. The second section analyzes the government of Arizona by giving an explanation of the executive branch, a list of Arizona state governors, and descriptions of the functions of its legislative and judicial branches of government. Both sections include illustrations or maps and reproducible student quizzes with answer sheets. Student activity worksheets and a bibliography are provided. Although designed to accompany student field trips to the Arizona State Capitol Museum, the resource guide and activities -

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness GRADE 6 Reading May 2019 RELEASED Copyright © 2019, Texas Education Agency. All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or portions of this work is prohibited without express written permission from the Texas Education Agency. STAAR Reading 10/02/2019 G6RSP19R_rev00 STAAR Reading 10/02/2019 G6RSP19R_rev00 READING Reading Page 3 STAAR Reading 10/02/2019 G6RSP19R_rev00 Read the selection and choose the best answer to each question. Then fill in the answer on your answer document. A Picture of Peace 1 When she was just seven years old, Michelle knew with certainty that she wanted to be a photographer when she grew up. That year she received her first camera, a small disposable one to use on the family vacation. At first she randomly clicked the button, not giving much thought to what she was doing. When her father examined her blurred images and aimless shots, he advised Michelle to look through the lens and think about what the resulting picture would look like. The next day Michelle saw a family of ducks, and remembering what her father had said, she lay down on the ground and waited for a duckling to waddle near her. That picture still hangs on her bedroom wall. 2 Now, six years later, Michelle was attempting to capture a sunset for a local photography contest. She groaned as storm clouds rolled in before the sun had a chance to cast its vibrant colors across the sky. 3 “Mom, I don’t think I’m ever going to get this shot!” Michelle complained, putting her camera equipment on the kitchen table and sighing with exasperation. -

Mayor's Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art

Mayor’s Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art Commission 100 Public Artworks: Back Bay, Beacon Hill, the Financial District and the North End 1. Lief Eriksson by Anne Whitney This life-size bronze statue memorializes Lief Eriksson, the Norse explorer believed to be the first European to set foot on North America. Originally sited to overlook the Charles River, Eriksson stands atop a boulder and shields his eyes as if surveying unfamiliar terrain. Two bronze plaques on the sculpture’s base show Eriksson and his crew landing on a rocky shore and, later, sharing the story of their discovery. When Boston philanthropist Eben N. Horsford commissioned the statue, some people believed that Eriksson and his crew landed on the shore of Massachusetts and founded their settlement, called Vinland, here. However, most scholars now consider Vinland to be located on the Canadian coast. This piece was created by a notable Boston sculptor, Anne Whitney. Several of her pieces can be found around the city. Whitney was a fascinating and rebellious figure for her time: not only did she excel in the typically ‘masculine’ medium of large-scale sculpture, she also never married and instead lived with a female partner. 2. Ayer Mansion Mosaics by Louis Comfort Tiffany At first glance, the Ayer Mansion seems to be a typical Back Bay residence. Look more closely, though, and you can see unique elements decorating the mansion’s façade. Both inside and outside, the Ayer Mansion is ornamented with colorful mosaics and windows created by the famed interior designer Louis Comfort Tiffany. -

David a Lester and the Kinsley Civil War Monument

Civil War Valor in Concrete by Randall M. Thies emorial Day, 1917: David Lester looked on with pride as the recently completed Civil War monument was unveiled in Hillside Cemetery, a short Mdistance northwest of Kinsley, Kansas. A Union vet- eran and longtime resident of the Kinsley area, Lester had a special reason to be proud of the new monu- ment: he was the artist who had created it. Memorial Day was always a special occasion, but the unveiling of the new monument made this day even more so, attracting a large crowd despite threat- ening weather and bad roads. After beginning the day with a band concert, speeches, and parade in downtown Kinsley, the crowd gathered at the ceme- tery to share in the dedication of its new monument. Uniformed members of the Knights of Pythias served as a ceremonial firing squad, while flower girls in white dresses provided a festive air. Honored as the The Kinsley Civil War monument photographed about the time of its dedication—Memorial Day, 1917. Randall W. Thies is an archeologist and cultural resource specialist with the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka and currently serves as state coor- dinator for the Kansas Save Outdoor Sculpture! (SOS!) project. A graduate of Washburn University, he received an M.A. in sociology (anthropology) from Iowa State University in 1979. 164 KANSAS HISTORY David A. Lester and the Kinsley Civil War Monument creator of the monument, David Lester also read the memorial service, as appropriate to his role as com- mander of Kinsley’s Timothy O. Howe Post 241 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a nationwide Union veterans organization.