Department of the Interior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threatened Birds of the Americas

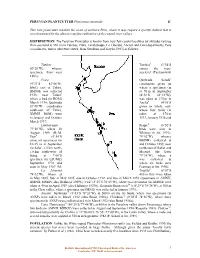

PERUVIAN PLANTCUTTER Phytotoma raimondii E1 This rare plantcutter inhabits the coast of northern Peru, where it may require a specific habitat that is now threatened by the almost complete cultivation of the coastal river valleys. DISTRIBUTION The Peruvian Plantcutter is known from very few coastal localities (at altitudes varying from sea-level to 550 m) in Tumbes, Piura, Lambayeque, La Libertad, Ancash and Lima departments, Peru (coordinates, unless otherwise stated, from Stephens and Traylor 1983) as follows: Tumbes Tumbes1 (3°34’S 80°28’W), whence comes the type- specimen, from near sea-level (Taczanowski 1883); Piura Quebrada Salada2 (4°33’S 81°08’W: coordinates given on label), east of Talara, where a specimen (in BMNH) was collected at 90 m in September 1933; near Talara3 (4°33’S 81°13’W), where a bird (in ROM) was taken at 275 m in March 1934; Quebrada Ancha4 (4°36’S 81°08’W: coordinates given on label), east- south-east of Talara, where four birds (in BMNH, ROM) were taken at 170 m in January and October 1933, January 1936 and March 1937; Lambayeque Reque5 (6°52’S 79°50’W), where 20 birds were seen in August 1989 (B. M. Whitney in litt. 1991); Eten6 (6°54’S 79°52’W), whence come six specimens (in BMNH) collected at 10-15 m in September and October 1899; near río Saña7, c.5 km north- north-east of Rafan and c.8 km south-west of Mocupé (the latter being at 7°00’S 79°38’W), where a specimen (in LSUMZ) was collected in September 1978 and where six birds were seen in May 1987 (M. -

Lista Roja De Las Aves Del Uruguay 1

Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay 1 Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Adrián B. Azpiroz, Laboratorio de Genética de la Conservación, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, Av. Italia 3318 (CP 11600), Montevideo ([email protected]). Matilde Alfaro, Asociación Averaves & Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Iguá 4225 (CP 11400), Montevideo ([email protected]). Sebastián Jiménez, Proyecto Albatros y Petreles-Uruguay, Centro de Investigación y Conservación Marina (CICMAR), Avenida Giannattasio Km 30.5. (CP 15008) Canelones, Uruguay; Laboratorio de Recursos Pelágicos, Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos, Constituyente 1497 (CP 11200), Montevideo ([email protected]). Cita sugerida: Azpiroz, A.B., M. Alfaro y S. Jiménez. 2012. Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay. Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente, Montevideo. Descargo de responsabilidad El contenido de esta publicación es responsabilidad de los autores y no refleja necesariamente las opiniones o políticas de la DINAMA ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes y no comprometen a estas instituciones. Las denominaciones empleadas y la forma en que aparecen los datos no implica de parte de DINAMA, ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes o de los autores, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades, personas, organizaciones, zonas o de sus autoridades, ni sobre la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. -

Systematic Relationships and Biogeography of the Tracheophone Suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 499–512 www.academicpress.com Systematic relationships and biogeography of the tracheophone suboscines (Aves: Passeriformes) Martin Irestedt,a,b,* Jon Fjeldsaa,c Ulf S. Johansson,a,b and Per G.P. Ericsona a Department of Vertebrate Zoology and Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, University of Stockholm, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Received 29 August 2001; received in revised form 17 January 2002 Abstract Based on their highly specialized ‘‘tracheophone’’ syrinx, the avian families Furnariidae (ovenbirds), Dendrocolaptidae (woodcreepers), Formicariidae (ground antbirds), Thamnophilidae (typical antbirds), Rhinocryptidae (tapaculos), and Conop- ophagidae (gnateaters) have long been recognized to constitute a monophyletic group of suboscine passerines. However, the monophyly of these families have been contested and their interrelationships are poorly understood, and this constrains the pos- sibilities for interpreting adaptive tendencies in this very diverse group. In this study we present a higher-level phylogeny and classification for the tracheophone birds based on phylogenetic analyses of sequence data obtained from 32 ingroup taxa. Both mitochondrial (cytochrome b) and nuclear genes (c-myc, RAG-1, and myoglobin) have been sequenced, and more than 3000 bp were subjected to parsimony and maximum-likelihood analyses. The phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial and nuclear genes were compared and found to be very similar. The results from the analysis of the combined dataset (all genes, but with transitions at third codon positions in the cytochrome b excluded) partly corroborate previous phylogenetic hypotheses, but several novel arrangements were also suggested. -

House Sparrow Eradication Attempt on Robinson Crusoe Island, Juan Fernández Archipelago, Chile

E. Hagen, J. Bonham and K. Campbell Hagen, E.; J. Bonham and K. Campbell. House sparrow eradication attempt on Robinson Crusoe Island, Juan Fernández Archipelago, Chile House sparrow eradication attempt on Robinson Crusoe Island, Juan Fernández Archipelago, Chile E. Hagen1, J. Bonham1 and K. Campbell1,2 1Island Conservation, Las Urbinas 53 Santiago, Chile. <[email protected]>.2School of Geography, Planning & Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia. Abstract House sparrows (Passer domesticus) compete with native bird species, consume crops, and are vectors for diseases in areas where they have been introduced. Sparrow eradication attempts aimed at eliminating these negative eff ects highlight the importance of deploying multiple alternative methods to remove individuals while maintaining the remaining population naïve to techniques. House sparrow eradication was attempted from Robinson Crusoe Island, Chile, in the austral winter of 2012 using an experimental approach sequencing passive multi-catch traps, passive single- catch traps, and then active multi-catch methods, and fi nally active single-catch methods. In parallel, multiple detection methods were employed and local stakeholders were engaged. The majority of removals were via passive trapping, and individuals were successfully targeted with active methods (mist nets and shooting). Automated acoustic recording, point counts and camera traps declined in power to detect individual sparrows as the population size decreased; however, we continued to detect sparrows at all population densities using visual observations, underscoring the importance of local residents’ participation in monitoring. Four surviving sparrows were known to persist at the conclusion of eff orts in 2012. Given the lack of formal biosecurity measures within the Juan Fernández archipelago, reinvasion is possible. -

Wood Warblers of Lake County (Field Guide)

Wood of Lake County An educational wildlife pamphlet provided by the Lake County Public Resources Department Parks & Trails Division 2 The Lake County Public Resources Department, Parks & Trails Division, manages more than three dozen parks, preserves and boat ramps. Lake County park rangers lead regularly scheduled nature in some of these parks. In partnership with the Lake County hikes, bird and butterfly surveys and other outdoor adventures Water Authority, Parks & Trails also schedules guided paddling adventures. For a listing of Lake County parks and events, call 352-253-4950, email [email protected] or visit Forwww.lakecountyfl.gov/parks. more information about birds that can be seen in Lake County, or bookstores. Information on birds is also available online at the check out a field guide to birds available at many local libraries Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, www.birds.cornell.edu. Bird watchers in Florida tend to bring a little more on their trips than their Northern peers. While the average temperature in Lake County is a mild 72°F, the summer months in Central Florida can be steamy. Outside enthusiasts are always encouraged to carry sunscreen to protect skin from sunburn, insect repellent to ward off mosquitoes and plenty of water to avoid dehydration. Sunscreen should be 15 SPF or higher and applied 20 minutes before. 3 Park rangers recommend these six popular comprehensive guides: • A Field Guide to the Birds, Eastern and Central North America (Fourth Edition, 1980, Roger Tory Peterson) • Stokes Field Guide to Birds, Eastern Region (First Edition, 1996, Donald and Lillian Stokes) • All the Birds of North America (First Edition, 1997, The American Bird Conservancy) • Field Guide to the Birds of North America (Fourth Edition, 2002, The National Geographic Society) • Focus Guide to the Birds of North America (First Edition, 2000, Kenn Kaufman) • The Sibley Guide to Birds (First Edition, 2000, David Allen Sibley) Insect repellent should contain DEET. -

Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by the Andean People of Canta, Lima, Peru

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266388116 Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Andean people of Canta, Lima, Peru Article in Journal of Ethnopharmacology · June 2007 DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.018 CITATIONS READS 38 30 3 authors, including: Percy Amilcar Pollito University of São Paulo 56 PUBLICATIONS 136 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Percy Amilcar Pollito on 14 November 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 111 (2007) 284–294 Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Andean people of Canta, Lima, Peru Horacio De-la-Cruz a,∗, Graciela Vilcapoma b, Percy A. Zevallos c a Facultad de Ciencias Biol´ogicas, Universidad Pedro Ruiz Gallo, Lambayeque, Peru b Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru c Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru Received 14 June 2006; received in revised form 15 November 2006; accepted 19 November 2006 Available online 2 December 2006 Abstract A survey aiming to document medicinal plant uses was performed in Canta Province Lima Department, in the Peruvians Andes of Peru. Hundred and fifty people were interviewed. Enquiries and informal personal conversations were used to obtain information. Informants were men and women over 30 years old, who work in subsistence agriculture and cattle farming, as well as herbalist. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. -

Contents Contents

Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU CONTENTS CONTENTS PERU, THE NATURAL DESTINATION BIRDS Northern Region Lambayeque, Piura and Tumbes Amazonas and Cajamarca Cordillera Blanca Mountain Range Central Region Lima and surrounding areas Paracas Huánuco and Junín Southern Region Nazca and Abancay Cusco and Machu Picchu Puerto Maldonado and Madre de Dios Arequipa and the Colca Valley Puno and Lake Titicaca PRIMATES Small primates Tamarin Marmosets Night monkeys Dusky titi monkeys Common squirrel monkeys Medium-sized primates Capuchin monkeys Saki monkeys Large primates Howler monkeys Woolly monkeys Spider monkeys MARINE MAMMALS Main species BUTTERFLIES Areas of interest WILD FLOWERS The forests of Tumbes The dry forest The Andes The Hills The cloud forests The tropical jungle www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 1 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU ORCHIDS Tumbes and Piura Amazonas and San Martín Huánuco and Tingo María Cordillera Blanca Chanchamayo Valley Machu Picchu Manu and Tambopata RECOMMENDATIONS LOCATION AND CLIMATE www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 2 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU Peru, The Natural Destination Peru is, undoubtedly, one of the world’s top desti- For Peru, nature-tourism and eco-tourism repre- nations for nature-lovers. Blessed with the richest sent an opportunity to share its many surprises ocean in the world, largely unexplored Amazon for- and charm with the rest of the world. This guide ests and the highest tropical mountain range on provides descriptions of the main groups of species Pthe planet, the possibilities for the development of the country offers nature-lovers; trip recommen- bio-diversity in its territory are virtually unlim- dations; information on destinations; services and ited. -

Peru: from the Cusco Andes to the Manu

The critically endangered Royal Cinclodes - our bird-of-the-trip (all photos taken on this tour by Pete Morris) PERU: FROM THE CUSCO ANDES TO THE MANU 26 JULY – 12 AUGUST 2017 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS and GUNNAR ENGBLOM This brand new itinerary really was a tour of two halves! For the frst half of the tour we really were up on the roof of the world, exploring the Andes that surround Cusco up to altitudes in excess of 4000m. Cold clear air and fantastic snow-clad peaks were the order of the day here as we went about our task of seeking out a number of scarce, localized and seldom-seen endemics. For the second half of the tour we plunged down off of the mountains and took the long snaking Manu Road, right down to the Amazon basin. Here we traded the mountainous peaks for vistas of forest that stretched as far as the eye could see in one of the planet’s most diverse regions. Here, the temperatures rose in line with our ever growing list of sightings! In all, we amassed a grand total of 537 species of birds, including 36 which provided audio encounters only! As we all know though, it’s not necessarily the shear number of species that counts, but more the quality, and we found many high quality species. New species for the Birdquest life list included Apurimac Spinetail, Vilcabamba Thistletail, Am- pay (still to be described) and Vilcabamba Tapaculos and Apurimac Brushfnch, whilst other montane goodies included the stunning Bearded Mountaineer, White-tufted Sunbeam the critically endangered Royal Cinclodes, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Peru: From the Cusco Andes to The Manu 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com These wonderful Blue-headed Macaws were a brilliant highlight near to Atalaya. -

Avian Nesting and Roosting on Glaciers at High Elevation, Cordillera Vilcanota, Peru

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 130(4):940–957, 2018 Avian nesting and roosting on glaciers at high elevation, Cordillera Vilcanota, Peru Spencer P. Hardy,1,4* Douglas R. Hardy,2 and Koky Castaneda˜ Gil3 ABSTRACT—Other than penguins, only one bird species—the White-winged Diuca Finch (Idiopsar speculifera)—is known to nest directly on ice. Here we provide new details on this unique behavior, as well as the first description of a White- fronted Ground-Tyrant (Muscisaxicola albifrons) nest, from the Quelccaya Ice Cap, in the Cordillera Vilcanota of Peru. Since 2005, .50 old White-winged Diuca Finch nests have been found. The first 2 active nests were found in April 2014; 9 were found in April 2016, 1 of which was filmed for 10 d during the 2016 nestling period. Video of the nest revealed infrequent feedings (.1 h between visits), slow nestling development (estimated 20–30 d), and feeding via regurgitation. The first and only active White-fronted Ground-Tyrant nest was found in October 2014, beneath the glacier in the same area. Three other unoccupied White-fronted Ground-Tyrant nests and an eggshell have been found since, all on glacier ice. At Quelccaya, we also observed multiple species roosting in crevasses or voids (caves) beneath the glacier, at elevations between 5,200 m and 5,500 m, including both White-winged Diuca Finch and White-fronted Ground-Tyrant, as well as Plumbeous Sierra Finch (Phrygilus unicolor), Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe (Attagis gayi), and Gray-breasted Seedsnipe (Thinocorus orbignyianus). These nesting and roosting behaviors are all likely adaptations to the harsh environment, as the glacier provides a microclimate protected from precipitation, wind, daily mean temperatures below freezing, and strong solar irradiance (including UV-B and UV-A). -

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed Alphabetically by Last Name Of

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author AOS 2019 Meeting 24-28 June 2019 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Variability in the Use of Acoustic Space Between propensity, renesting intervals, and renest reproductive Two Tropical Forest Bird Communities success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) by fol- lowing 1,922 nests and 1,785 unique breeding adults Patrick J Hart, Kristina L Paxton, Grace Tredinnick from 2014 2016 in North and South Dakota, USA. The apparent renesting rate was 20%. Renesting propen- When acoustic signals sent from individuals overlap sity declined if reproductive attempts failed during the in frequency or time, acoustic interference and signal brood-rearing stage, nests were depredated, reproduc- masking occurs, which may reduce the receiver’s abil- tive failure occurred later in the breeding season, or ity to discriminate information from the signal. Under individuals had previously renested that year. Addi- the acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH), acoustic space is tionally, plovers were less likely to renest on reservoirs a resource that organisms may compete for, and sig- compared to other habitats. Renesting intervals de- naling behavior has evolved to minimize overlap with clined when individuals had not already renested, were heterospecific calling individuals. Because tropical after second-year adults without prior breeding experi- wet forests have such high bird species diversity and ence, and moved short distances between nest attempts. abundance, and thus high potential for competition for Renesting intervals also decreased if the attempt failed acoustic niche space, they are good places to examine later in the season. Lastly, overall reproductive success the way acoustic space is partitioned. -

Satellite Imagery Reveals New Critical Habitat for Endangered Bird Species in the High Andes of Peru

Vol. 13: 145–157, 2011 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online February 16 doi: 10.3354/esr00323 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Satellite imagery reveals new critical habitat for Endangered bird species in the high Andes of Peru Phred M. Benham1, Elizabeth J. Beckman1, Shane G. DuBay1, L. Mónica Flores2, Andrew B. Johnson1, Michael J. Lelevier1, C. Jonathan Schmitt1, Natalie A. Wright1, Christopher C. Witt1,* 1Museum of Southwestern Biology and Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87110, USA 2Centro de Ornitologia y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Urb. Huertos de San Antonio, Surco, Lima, Peru ABSTRACT: High-resolution satellite imagery that is freely available on Google Earth provides a powerful tool for quantifying habitats that are small in extent and difficult to detect by medium- resolution Landsat imagery. Relictual Polylepis forests of the high Andes are of critical importance to several globally threatened bird species, but, despite growing international attention to Polylepis conservation, many gaps remain in our knowledge of its distribution. We examined high-resolution satellite imagery in Google Earth to search for new areas of Polylepis in south-central Peru that potentially support Polylepis-specialist bird species. In central Apurímac an extensive region of high- resolution satellite imagery contained 127 Polylepis fragments, totaling 683.15 ha of forest ranging from 4000 to 4750 m a.s.l. Subsequent fieldwork confirmed the presence of mature Polylepis forest and all 6 Polylepis-specialist bird species, 5 of which are considered globally threatened. Our find- ings (1) demonstrate the utility of Google Earth for applied conservation and (2) suggest improved prospects for the persistence of the Polylepis-associated avifauna.