Yangon University of Economics Master of Development Studies Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly Briefing Note Southeastern Myanmar 5-11 June 2021 (Limited Distribution)

Weekly Briefing Note Southeastern Myanmar 5-11 June 2021 (Limited Distribution) This weekly briefing note, covering humanitarian developments in Southeastern Myanmar from 5 June to 11 June, is produced by the Kayin Inter-Agency Coordination of the Southeastern Myanmar Working Group. Highlights • The import of soap, detergent and toothpaste from Thailand through the Myawaddy border was suspended on 4 June, according to a letter of notification from the Trades Department.1 • In Kayin State, clashes between the Tatmadaw and Karen National Union (KNU) was observed in Kyainseikgyi, Hpapun and Myawaddy townships and Thandaung town during the week. • A letter ordering the suspension of activities and temporary closure of offices of INGOs in Tanintharyi Region was issued by the Department of Social Welfare on 2 June. The closure of INGOs offices is likely to impact access to services and assistance by vulnerable people in the region. • The Karen National Liberation Army's (KNLA) Chief, General Saw Johny released a statement on 9 June, indicating that the KNLA and its members will follow political leadership of the Karen National Union (KNU). According to the statement signed by Gen. Saw Johny, the KNLA will follow the announcement that was released by the KNU's chairman Saw Mutu Say Poe on 10 May and will follow the framework of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) signed by the KNU. The statement also stated that KNLA members must comply with the military rules of the KNLA.2 • The security situation continues to deteriorate in Kayah State. Over 100,000 remain displaced as clashes and military reinforcements brought in by the Tatmadaw continued throughout the week. -

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department

Leaflet No. 24 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation Forest Department Assessing different livelihood of the local people and causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the Kayah State Dr. Chaw Chaw Sein, Staff Officer Dr. Thaung Naing Oo, Director Kyi Phyu Aung, Range Officer Forest Research Institute December, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS i Abstract ii 1 Introduction 1 2 Objectives 2 3 Literature Review 2 3.1 What do we mean by sustainable livelihoods? 2 3.2 Why are sustainable livelihoods important for conservation? 3 3.3 How do we identify locally appropriate livelihoods strategies? 3 4 Material and Method 5 4.1 Study Area 5 4.2 Data collection and analysis 6 5 Results and Discussion 6 5.1 Livelihood surveys in the Kayah Region 6 5.2 Causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the study area 12 6 Conclusions and Recommendation 15 7 Acknowledgements 17 8 References 18 ၊ ၊ ၊ ၊ ၁.၄% Assessing different livelihood of the local people and causes of forest degradation and deforestation in the Kayah State Dr. Chaw ChawSein, Staff Officer Dr. Thaung Naing Oo, Director Thein Saung, Staff Officer Kyi Phyu Aung , Range Officer Abstract About annual rate of 1.4% of the forest degradation and deforestation was occurred in Myanmar. There are many causes of deforestation and forest degradation. Especially in the hilly region like Kayah state, the main causes of forest degradation and deforestation are due to shifting cultivation. The present study reports different livelihood activities to settle their daily needs in the Kayah areas and the causes of forest degradation and deforestation. -

Courts Manual

COURTS MANUAL GQCO-O 0COCO ฮ่3 ร:§o$§<8: L CD FOURTH EDITION 1999 Z c c s c n o o o s p : รํเะ 3j]o t' CO CO GO 0 3 gS ’ขนนร?•แ•.ช 15V SUPREME COURT TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 PARA LEGAL PRACTIONERS AND PETITION WRITERS CHAPTER I- Advocates and Pleaders 1................. 1-11 CHAPTER แ- Petition Writers ............................... 12 PART n INSTRUCTIONS AND ORDERS RELATING TO BOTH CIVIL AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CHAPTER III- Adminstation and Conduct of Cases...... 13-48 CHAPTER IV- Evidence-Prisoners Act-Oaths Act ... 49-75 CHAPTER V- Court Fees and Stamps- Court Free Act-Stamps Act ..................... ......... 76-102 CHAPTER VI- Translation and Copies- Inspection ofRecords ........... .......................... 103-109 PART III CIVIL PROCEDURE CHAPTER VII- Procedure in Suits and Miscellaneous Proceedings ...................................... J10-182 CHAPTER VIII- Procedure in Execution ..................... 183-283 CHAPTER IX- Arrest and attachment before Judgment- Injunction .... ....................... ...... 284-288 CHAPTER X- Commissions .................................... 289-293 CHAPTER XI- Pauper Suits ................................... 294-297’ CHAPTER xn - Suits by or againt Goverment Attorney- General ................ ............... 289-299 CHAPTER Xffl- Appeal, Refemce and Revision ........ 300-309 CHAPTER XIV- Procedure under Special Enactments- 1. Specific Relief Act .................... 310-311 2. Tranfer of Property Act .......... 312-315 3. Myanmar Small Cause Courts Act.. 316-321 4. Land Acquisition Act .................... -

India-Myanmar-Bangladesh Border Region

MyanmarInform ationManage mUnit e nt India-Myanmar-Banglade shBord eRegion r April2021 92°E 94°E 96°E Digboi TaipiDuidam Marghe rita Bom dLa i ARUN ACHALPRADESH N orthLakhimpur Pansaung ARUN ACHAL Itanagar PRADESH Khonsa Sibsagar N anyun Jorhat INDIA Mon DonHee CHINA Naga BANGLA Tezpur DESH Self-Administered Golaghat Mangaldai Zone Mokokc hung LAOS N awgong(nagaon) Tuensang Lahe ASSAM THAILAND Z unhe boto ParHtanKway 26° N 26° Hojai Dimapur N 26° Hkamti N AGALAN D Kachin Lumd ing Kohima State Me huri ChindwinRiver Jowai INDIA LayShi Maram SumMaRar MEGHALAYA Mahur Kalapahar MoWaing Lut Karimganj Hom alin Silchar Imphal Sagaing ShwePyi Aye Region Kalaura MAN IPUR Rengte Kakc hing Myothit Banmauk MawLu Churachandpur Paungbyin Indaw Katha Thianship Tamu TRIPURA Pinlebu 24° N 24° W untho N 24° Cikha Khampat Kawlin Tigyaing Aizawal Tonzang Mawlaik Rihkhawdar Legend Ted im Kyunhla State/RegionCapital Serc hhip Town Khaikam Kalewa Kanbalu Ge neralHospital MIZORAM Kale W e bula TownshipHospital Taze Z e eKone Bord eCrossing r Falam Lunglei Mingin AirTransport Facility Y e -U Khin-U Thantlang Airport Tabayin Rangamati Hakha Shwebo TownshipBoundary SaingPyin KyaukMyaung State/RegionBoundary Saiha Kani BANGLA Budalin W e tlet BoundaryInternational Ayadaw MajorRoad Hnaring Surkhua DESH Sec ondaryRoad Y inmarbin Monywa Railway Keranirhat SarTaung Rezua Salingyi Chaung-U Map ID: MIMU1718v01 22° N 22° Pale Myinmu N 22° Lalengpi Sagaing Prod uctionApril62021 Date: Chin PapeSize r A4 : Projec tion/Datum:GCS/WGS84 Chiringa State Myaung SourcData Departme e : ofMe nt dService ical s, Kaladan River Kaladan TheHumanitarian ExchangeData Matupi Magway BasemMIMU ap: PlaceName General s: Adm inistrationDepartme (GAD)and field nt Cox'sBazar Region sourcTransliteration e s. -

Peace Is Living with Dignity

PEACE IS LIVING WITH DIGNITY VOICES OF COMMUNITIES FROM MYanmar’s ceasefIRE AREAS IN 2016 PEACE IS LIVING WITH DIGNITY Voices of Communities from Myanmar’s ceasefire areas in 2016 i PEACE IS LIVING WITH DIGNITY Voices of Communities from Myanmar’s ceasefire areas in 2016 Listening methodology development: Soth Plai Ngarm Listening Project Implementation (Training, Processing, Writing) Coordinator and Editor: Karen Simbulan Team members: Laurens Visser, Tengku Shahpur, Harshadeva Amarathunga Myanmar Partner Organisations Karuna Myanmar Social Services (Kachin) Ta’ang Student and Youth Union (Northern Shan) Pyi Nyein Thu Kha (Southern Shan) Karen Development Network (Kayin) Kayah State Peace Monitoring Network (Kayah) Mon Women Network (Mon) Cover photo: Karlos Manlupig Inside photographs: Zabra Yu Siwa, Shutterstock, Listener from Northern Shan Copy-editing: Husnur Esthiwahyu Lay-out: Boonruang Song-ngam Publisher: Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies Funding: Peace Support Fund ISBN- 13: 978 99963 856 4 3 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS) is grateful to our Myanmar partner organisations that provided invaluable assistance throughout the project. We could not have done this without you. We are especially grateful to all the individuals who volunteered to be listeners. We appreciate the time, energy and enthusiasm that you demonstrated throughout the process, and your willingness to travel to remote areas. We would also like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the community members from Kachin, Northern Shan, Southern Shan, Kayah, Kayin, and Mon states who were willing to take the time out of their busy lives to share their opinions, experiences, knowledge, concerns and hopes for the future. -

Raising the Curtain

Raising the Curtain Cultural Norms, Social Practices and Gender Equality in Myanmar 1 We, both women and men, hold equal opportunities and chances since we were born, as we all are, human beings. Most women think that these opportunities and favours are given by men. No, these are our own opportunities and chances to live equally and there is no need to thank men for what they are not doing. Focus Group Discussion with Muslim women, aged 18-25, Mingalartaung Nyunt Township The Gender Equality Network Yangon, Myanmar © All rights reserved Published in Yangon, Myanmar, Gender Equality November 2015 Network 2 Cultural Norms, Social Practices and Gender Equality in Myanmar 3 Contents Acronyms 6 Acknowledgements 7 Executive Summary 8 1. Introduction 10 1.1 Background and Rationale 12 1.2 Objectives and Study Questions 12 1.3 Methodology - In Brief 13 2. Setting the Scene 16 2.1 ‘The Problem is that the Problem is not Seen as a Problem’ 17 2.2 Historical Narratives: Women’s High Status and Comparisons with Other Countries 18 2.3 Gender Inequality and Gender Discrimination: Where is the Problem? 21 2.4 Gender Equality as a ‘Western’ Concept 25 3. Cultural and Religious Norms and Practices 26 3.1 Culture in Myanmar, and Myanmar Culture 27 3.2 The Inseparability of Culture and Religion 29 3.3 Women as Bearers of Culture 30 3.4 The Role of Nuns in Buddhism 32 3.5 Hpon, Respect and Male Superiority 34 3.6 Purity, Female Inferiority and Exclusion 37 3.7 Modesty, Male Sexuality and the Importance of Women’s Dress 38 3.8 The Construction of Ideal Masculinity 41 3.9 Letting the Birds Rest on the Pagoda: Controlling the Self, Enduring Hardship and Sacrificing 42 4. -

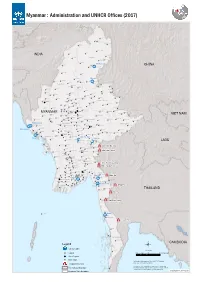

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Earth Rights Abuses in Burma Exposed

Gaining Ground: Earth Rights Abuses in Burma Exposed Earth Rights School of Burma Class of 2008 Preface People can create a better world if they have the desire, enthusiasm and knowledge to do so. Furthermore, unity of thought and unity of action are needed in the international community to bring about positive changes and sustainable development around the globe. In a long list of important goals, eradication of poverty and protection and promotion of human rights and environmental rights are top priorities. People power is pivotal and improving the connections among individuals, organizations and governments is essential. Greater knowledge is important at every level and every actor in the international community must strive to create a better world in the future. Of course, this improvement would come from both local and global actions. In fact, to my knowledge, the students and EarthRights School (ERS) itself are trying their best to cooperate and to coordinate with the international community for the above-mentioned noble tasks. By starting from localized actions, many ethnic youths from various areas of Burma come, study and have been working together at ERS. They exchange their experiences and promote knowledge and expertise not only during their school term but also after they graduate and through practical work that improves society. In Burma, according to the international communitys highly-regarded research and field documents, human rights violations are rampant, poverty is too high, environmental issues are neglected and good governance is non-existent. This may be a normal situation under military dictatorships around the world but it is not a permanent situation and history has proved that if democratic people have enough power, things will change sooner or later. -

Sagaing Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Sagaing Region 93° E 94° E 95° E 96° E 97° E Puta-O Pansaung INDIA !( CHINA N N Ü Nanyun ° ° 7 7 2 2 Nanyun !( Don Hee Shin Bway Yang !( THAILAND Tanai Lahe Lahe N Hkamti N ° Htan Par Kway ° 6 6 2 !( 2 Hkamti KACHIN STATE Hpakant Hkamti District Kamaing !( Lay Shi Myitkyina Sum Ma Rar !( Mogaung .! INDIA Lay Shi Mo Paing Lut N !( N Hopin ° ° 5 Homalin !( 5 2 2 Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo !( Shwe Pyi Aye !( Dawthponeyan !( Myothit !( SAGAING REGION Myo Hla Banmauk !( Banmauk Indaw Tamu Paungbyin Bhamo Indaw Katha Shwegu Momauk Tamu Katha Mansi Paungbyin Pinlebu Katha District Tamu N N ° ° 4 Wuntho 4 2 District 2 Cikha Pinlebu !( Mawlaik District Wuntho Khampat Tigyaing !( Kawlin Tigyaing Kawlin Mawlaik Mawlaik Tonzang Takaung Mabein Kyunhla !( Tedim Rihkhawdar Kanbalu District !( Kyunhla Legend Manton Kalewa Kalewa Kale Kanbalu .! State/Region Capital Mongmit Main Town Namtu !( N Kale Kale District Taze Kanbalu Other Town N ° CHIN STATE Namhsan ° 3 Taze 3 2 Falam Mogoke 2 Mingin Thabeikkyin Township Boundary Mingin Ye-U State/Region Boundary Khin-U Monglon Mongngawt Ye-U !( !( Thantlang Khin-U International Boundary Tabayin Kyauk Hakha Tabayin Hsipaw .! Myaung Road Shwebo District !( Singu Kyaukme Kani Shwebo Shwebo Hkamti Budalin Map ID: MIMU764v04 Kani Wetlet Kale Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 Budalin Ayadaw Nawnghkio Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Kanbalu Monywa Ayadaw Wetlet Yinmabin District Madaya Data Sources: MIMU Gangaw District Katha Yinmabin Monywa Base Map: MIMU Monywa Mawlaik Boundaries: MIMReUz/uWaFP !( Yinmabin Sagaing District Patheingyi Pyinoolwin N N Monywa ° Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Chaung-U Myinmu Sagaing ° 2 Pale 2 2 Salingyi Myinmu .! 2 translated by MIMU Pale Sagaing Sagaing Salingyi Chaung-U Mandalay City .! !( Email: [email protected] Myaung Ngazun Myitnge Shwebo Website: www.themimu.info Tada-U Myaung Tilin Sintgaing Tamu Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers Intaw 2017. -

Food Security Update - April 2014 Early Warning and Situation Reports

Food Security Update - April 2014 Early Warning and Situation Reports Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Purpose and Interpretation: Food Security Updates (FSUs) have two key components; 1) an Early Warning (EW) section and 2) a Situation Report (SitRep) from main States and Regions. The EW section outlines the key events occurring throughout Myanmar that are currently impacting the food security situation. By highlighting these events, it is possible to identify townships where food security status is likely to deteriorate in the short term, facilitating decision-making and response. Methodologically, WFP classifies the severity of shocks as Low, Moderate or High, depending on the likelihood that a shock is significant enough to result in deteriorations in key food security indicators as defined by the Food Security Information Network (FSIN). Indicator scores are then summed to determine a shock severity score. This methodology is summa- rized below. The SitRep, by contrast, provides general information on a monthly basis about the food security situation in key Regions and States in Myanmar. SitReps sum- marize the evolving food security situation and help provide context to more in-depth FSIN periodic monitoring rounds. Source of information: Information included in Food Security Updates (FSUs) comes from a variety of sources, including observations from field staff, information from assessment activities, community reports or requests for assistance, government requests for action and information from media outlets. Monthly Updates can be accessed online at http://www.fsinmyanmar.net. Early Warning Report: Key Shocks Reported in April Recent FSIN Shock Region/ classifica- Severity Shock Township severity 1 Direct effect and likely human impact State tions score Post Pre Across Magway region, water ponds have dried up and most villages have to purchase drink- Low Dry Spells Magway All townships 6 ing water at a cost of 200-250 MMK a barrel. -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. in Five

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT. BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E., M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. III. RANGOON: PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME III. Page. Page. Page. Ralang 1 Sagaing 36 Sa-le-ywe 83 Ralôn or Ralawn ib -- 64 Sa-li ib. Rapum ib -- ib. Sa-lim ib. Ratanapura ib -- 65 Sa-lin ib. Rawa ib. Saga Tingsa 76 -- 84 Rawkwa ib. Sagônwa or Sagong ib. Salin ib. Rawtu or Maika ib. Sa-gu ib. Sa-lin chaung 86 Rawva 2 -- ib. Sa-lin-daung 89 Rawvan ib. Sagun ib -- ib. Raw-ywa ib. Sa-gwe ib. Sa-lin-gan ib. Reshen ib. Sa-gyan ib. Sa-lin-ga-thu ib. Rimpi ib. Sa-gyet ib. Sa-lin-gôn ib. Rimpe ib. Sagyilain or Limkai 77 Sa-lin-gyi ib. Rosshi or Warrshi 3 Sa-gyin ib -- 90 Ruby Mines ib. Sa-gyin North ib. Sallavati ib. Ruibu 32 Sa-gyin South ib. Sa-lun ib. Rumklao ib. a-gyin San-baing ib. Salween ib. Rumshe ib. Sa-gyin-wa ib. Sama 103 Rutong ib. Sa-gyu ib. Sama or Suma ib. Sai Lein ib. Sa-me-gan-gôn ib. Sa-ba-dwin ib. Saileng 78 Sa-meik ib. Sa-ba-hmyaw 33 Saing-byin North ib. Sa-meik-kôn ib. Sa-ban ib. -

Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue

7/24/2016 Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue Myanmar LANGUAGES Akeu [aeu] Shan State, Kengtung and Mongla townships. 1,000 in Myanmar (2004 E. Johnson). Status: 5 (Developing). Alternate Names: Akheu, Aki, Akui. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. Comments: Non-indigenous. More Information Akha [ahk] Shan State, east Kengtung district. 200,000 in Myanmar (Bradley 2007a). Total users in all countries: 563,960. Status: 3 (Wider communication). Alternate Names: Ahka, Aini, Aka, Ak’a, Ekaw, Ikaw, Ikor, Kaw, Kha Ko, Khako, Khao Kha Ko, Ko, Yani. Dialects: Much dialectal variation; some do not understand each other. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. More Information Anal [anm] Sagaing: Tamu town, 10 households. 50 in Myanmar (2010). Status: 6b (Threatened). Alternate Names: Namfau. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Sal, Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Northern. Comments: Non- indigenous. Christian. More Information Anong [nun] Northern Kachin State, mainly Kawnglangphu township. 400 in Myanmar (2000 D. Bradley), decreasing. Ethnic population: 10,000 (Bradley 2007b). Total users in all countries: 450. Status: 7 (Shifting). Alternate Names: Anoong, Anu, Anung, Fuchve, Fuch’ye, Khingpang, Kwingsang, Kwinp’ang, Naw, Nawpha, Nu. Dialects: Slightly di㨽erent dialects of Anong spoken in China and Myanmar, although no reported diഡculty communicating with each other. Low inherent intelligibility with the Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Lexical similarity: 87%–89% with Anong in Myanmar and Anong in China, 73%–76% with T’rung [duu], 77%–83% with Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Central Tibeto-Burman, Nungish. Comments: Di㨽erent from Nung (Tai family) of Viet Nam, Laos, and China, and from Chinese Nung (Cantonese) of Viet Nam.