Genetic Testing for Acute Myeloid Leukemia AHS-M2062

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and Biliary Tract Cancer

diagnostics Review Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and Biliary Tract Cancer Shunsuke Kato Department of Clinical Oncology, Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-1-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8421, Japan; [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-5802-1543 Abstract: The prognosis of patients with solid tumours has remarkably improved with the develop- ment of molecular-targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, the improvements in the prognosis of pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer is delayed compared to other carcinomas, and the 5-year survival rates of distal-stage disease are approximately 10 and 20%, respectively. How- ever, a comprehensive analysis of tumour cells using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project has led to the identification of various driver mutations. Evidently, few mutations exist across organs, and basket trials targeting driver mutations regardless of the primary organ are being actively conducted. Such basket trials not only focus on the gate keeper-type oncogene mutations, such as HER2 and BRAF, but also focus on the caretaker-type tumour suppressor genes, such as BRCA1/2, mismatch repair-related genes, which cause hereditary cancer syndrome. As oncogene panel testing is a vital approach in routine practice, clinicians should devise a strategy for improved understanding of the cancer genome. Here, the gene mutation profiles of pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer have been outlined and the current status of tumour-agnostic therapy in these cancers has been reported. Keywords: pancreatic cancer; biliary tract cancer; targeted therapy; solid tumours; driver mutations; agonist therapy Citation: Kato, S. Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and 1. -

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA for APPROVAL Initial Evaluation Target Agent(S) Will Be Approved When ONE of the Following Is Met: 1

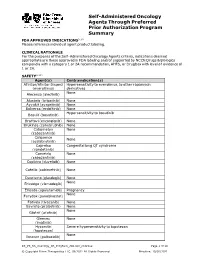

Self-Administered Oncology Agents Through Preferred Prior Authorization Program Summary FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS3-104 Please reference individual agent product labeling. CLINICAL RATIONALE For the purposes of the Self -Administered Oncology Agents criteria, indications deemed appropriate are those approved in FDA labeling and/or supported by NCCN Drugs & Biologics compendia with a category 1 or 2A recommendation, AHFS, or DrugDex with level of evidence of 1 or 2A. SAFETY3-104 Agent(s) Contraindication(s) Afinitor/Afinitor Disperz Hypersensitivity to everolimus, to other rapamycin (everolimus) derivatives None Alecensa (alectinib) Alunbrig (brigatinib) None Ayvakit (avapritinib) None Balversa (erdafitinib) None Hypersensitivity to bosutinib Bosulif (bosutinib) Braftovi (encorafenib) None Brukinsa (zanubrutinib) None Cabometyx None (cabozantinib) Calquence None (acalabrutinib) Caprelsa Congenital long QT syndrome (vandetanib) Cometriq None (cabozantinib) Copiktra (duvelisib) None Cotellic (cobimetinib) None Daurismo (glasdegib) None None Erivedge (vismodegib) Erleada (apalutamide) Pregnancy None Farydak (panobinostat) Fotivda (tivozanib) None Gavreto (pralsetinib) None None Gilotrif (afatinib) Gleevec None (imatinib) Hycamtin Severe hypersensitivity to topotecan (topotecan) None Ibrance (palbociclib) KS_PS_SA_Oncology_PA_ProgSum_AR1020_r0821v2 Page 1 of 19 © Copyright Prime Therapeutics LLC. 08/2021 All Rights Reserved Effective: 10/01/2021 Agent(s) Contraindication(s) None Iclusig (ponatinib) Idhifa (enasidenib) None Imbruvica (ibrutinib) -

Pharmacy Pre-Authorization Criteria

PHARMACY PRE-AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA DRUG (S) Oncology Medications: Sprycel (dasatinib) Afinitor (everolimus) Stivarga (regorafenib) Caprelsa (vandetanib) Sutent (sunitinib) Gilotrif (afatinib dimaleate) Tarceva (erlotinob) Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) Temodar (temozolomide) Ibrance (palbociclib) Tepadina (thiotepa) Idhifa (enasidenib) Thalomid (thalidomide) Iressa (gefitinib) Vantas (histrelin acetate) Kisqali (ribociclib) Venclexta (venetoclax) Lenvima (lenvatinib) Verzenio (abemaciclib) Nerlynx (neratinib) Vidaza (azacitidine) Nexavar (sorafenib) Votrient (pazopanib) Ninlaro (ixazomib) Xalkori (crizotinib) Odomzo (sonidegib) Xeloda (capecitabine) Zydelig (idelalisib) Zykadia (certinib) Zytiga (abiraterone acetate) PHARMACY PRE-AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA POLICY # 21107 CRITERIA The above medications are covered when the following criteria are met: 1. Ordered by an oncologist or hematologist AND 2. All FDA Approved Indications OR 3. Chemo agent is listed in an accepted Compendia for treatment of cancer type, OR - National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs and Biologics Compendium, level of evidence 1, 2A, or 2B - Thomson Micromedex DrugDex - Chemo agent is recommended for cancer type in formal clinical studies published in at least 2 peer reviewed professional medical journals, published in the United States or Great Britain Coverage Duration: Initial: 3 months Continuation: 6 months. Afinitor, Gilotrif, Gleevec, Ibrance, Idhifa, Iressa, Kisqali, Lenvima, Nexavar, Ninlaro, Odomzo, Sprycel, Stivarga, Sutent, Tarceva, Temodar, Thalomid, -

Variations in Microrna-25 Expression Influence the Severity of Diabetic

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Variations in MicroRNA-25 Expression Influence the Severity of Diabetic Kidney Disease † † † Yunshuang Liu,* Hongzhi Li,* Jieting Liu,* Pengfei Han, Xuefeng Li, He Bai,* Chunlei Zhang,* Xuelian Sun,* Yanjie Teng,* Yufei Zhang,* Xiaohuan Yuan,* Yanhui Chu,* and Binghai Zhao* *Heilongjiang Key Laboratory of Anti-Fibrosis Biotherapy, Medical Research Center, Heilongjiang, People’s Republic of China; and †Clinical Laboratory of Hong Qi Hospital, Mudanjiang Medical University, Heilongjiang, People’s Republic of China ABSTRACT Diabetic nephropathy is characterized by persistent albuminuria, progressive decline in GFR, and second- ary hypertension. MicroRNAs are dysregulated in diabetic nephropathy, but identification of the specific microRNAs involved remains incomplete. Here, we show that the peripheral blood from patients with diabetes and the kidneys of animals with type 1 or 2 diabetes have low levels of microRNA-25 (miR-25) compared with those of their nondiabetic counterparts. Furthermore, treatment with high glucose decreased the expression of miR-25 in cultured kidney cells. In db/db mice, systemic administration of an miR-25 agomir repressed glomerular fibrosis and reduced high BP. Notably, knockdown of miR-25 in normal mice by systemic administration of an miR-25 antagomir resulted in increased proteinuria, extracellular matrix accumulation, podocyte foot process effacement, and hypertension with renin-angiotensin system activation. However, excessive miR-25 did not cause kidney dysfunction in wild-type mice. RNA sequencing showed the alteration of miR-25 target genes in antagomir-treated mice, including the Ras-related gene CDC42. In vitro,cotrans- fection with the miR-25 antagomir repressed luciferase activity from a reporter construct containing the CDC42 39 untranslated region. -

211192Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 211192Orig1s000 RISK ASSESSMENT and RISK MITIGATION REVIEW(S) Division of Risk Management (DRISK) Office of Medication Error Prevention and Risk Management (OMEPRM) Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Application Type NDA Application Number 211192 PDUFA Goal Date August 21, 2018 OSE RCM # 2017-2612; 2017-2614 Reviewer Name(s) Till Olickal, Ph.D., Pharm.D. Team Leader Elizabeth Everhart, MSN, RN, ACNP Division Director Cynthia LaCivita, Pharm.D. Review Completion Date June 6, 2018 Subject Review to determine if a REMS is necessary Established Name Ivosidenib Trade Name Tibsovo Name of Applicant Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Therapeutic Class Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 inhibitor Formulation(s) 250 mg tablet Dosing Regimen 500 mg orally once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. 1 Reference ID: 4273770 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Product Information .......................................................................................................................................... -

Horizon Scanning Status Report June 2019

Statement of Funding and Purpose This report incorporates data collected during implementation of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Health Care Horizon Scanning System, operated by ECRI Institute under contract to PCORI, Washington, DC (Contract No. MSA-HORIZSCAN-ECRI-ENG- 2018.7.12). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its content. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of PCORI. An intervention that potentially meets inclusion criteria might not appear in this report simply because the horizon scanning system has not yet detected it or it does not yet meet inclusion criteria outlined in the PCORI Health Care Horizon Scanning System: Horizon Scanning Protocol and Operations Manual. Inclusion or absence of interventions in the horizon scanning reports will change over time as new information is collected; therefore, inclusion or absence should not be construed as either an endorsement or rejection of specific interventions. A representative from PCORI served as a contracting officer’s technical representative and provided input during the implementation of the horizon scanning system. PCORI does not directly participate in horizon scanning or assessing leads or topics and did not provide opinions regarding potential impact of interventions. Financial Disclosure Statement None of the individuals compiling this information have any affiliations or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report. Public Domain Notice This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission. Citation of the source is appreciated. All statements, findings, and conclusions in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) or its Board of Governors. -

209606Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 209606Orig1s000 MULTI-DISCIPLINE REVIEW Summary Review Office Director Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Clinical Review Non-Clinical Review Statistical Review Clinical Pharmacology Review NDA Multidisciplinary Review and Evaluation Application Number(s) NDA 209606 Application Type Original 505(b)(1) Priority or Standard Priority Submit Date(s) December 30, 2016 Received Date(s) December 30, 2016 PDUFA Goal Date August 30, 2017 Division/Office DHP/OHOP Review Completion Date July 28, 2017 Applicant Celgene Corporation Established Name Enasidenib (Proposed) Trade Name IDHIFA® Pharmacologic Class Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 inhibitor Formulation(s) Tablets, 50mg and 100mg Dosing Regimen 100 mg once daily Applicant Proposed IDHIFA is indicated for the treatment of patients with relapsed or Indication(s)/Population(s) refractory acute myeloid leukemia with an IDH2 mutation Recommendation on Regular approval Regulatory Action Recommended IDHIFA is an isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 inhibitor indicated for the Indication(s)/Population(s) treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with an isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test. Reference ID: 4131433 Multidisciplinary Review and Evaluation NDA 209606 IDHIFA® (enasidenib) Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Tables .............................................................................................................................. -

Enasidenib Drives Human Erythroid Differentiation Independently of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2

The Journal of Clinical Investigation CONCISE COMMUNICATION Enasidenib drives human erythroid differentiation independently of isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 Ritika Dutta,1,2 Tian Yi Zhang,1,2 Thomas Köhnke,1 Daniel Thomas,1 Miles Linde,1 Eric Gars,1 Melissa Stafford,1 Satinder Kaur,1 Yusuke Nakauchi,1 Raymond Yin,1 Armon Azizi,1 Anupama Narla,3 and Ravindra Majeti1,2 1Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Cancer Institute, and Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA. 2Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA. 3Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA. Cancer-related anemia is present in more than 60% of newly diagnosed cancer patients and is associated with substantial morbidity and high medical costs. Drugs that enhance erythropoiesis are urgently required to decrease transfusion rates and improve quality of life. Clinical studies have observed an unexpected improvement in hemoglobin and RBC transfusion- independence in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with the isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) mutant- specific inhibitor enasidenib, leading to improved quality of life without a reduction in AML disease burden. Here, we demonstrate that enasidenib enhanced human erythroid differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors. The phenomenon was not observed with other IDH1/2 inhibitors and occurred in IDH2-deficient CRISPR-engineered progenitors independently of D-2-hydroxyglutarate. The effect of enasidenib on hematopoietic progenitors was mediated by protoporphyrin accumulation, driving heme production and erythroid differentiation in committed CD71+ progenitors rather than hematopoietic stem cells. Our results position enasidenib as a promising therapeutic agent for improvement of anemia and provide the basis for a clinical trial using enasidenib to decrease transfusion dependence in a wide array of clinical contexts. -

C/Ebpα Is an Essential Collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-Mediated Leukemogenesis

C/EBPα is an essential collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis Cailin Collinsa, Jingya Wanga, Hongzhi Miaoa, Joel Bronsteina, Humaira Nawera, Tao Xua, Maria Figueroaa, Andrew G. Munteana, and Jay L. Hessa,b,1 aDepartment of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; and bIndiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Edited* by Louis M. Staudt, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved May 19, 2014 (received for review February 12, 2014) Homeobox A9 (HOXA9) is a homeodomain-containing transcrip- with Hoxa9. In addition, C/EBP recognition motifs are enriched tion factor that plays a key role in hematopoietic stem cell expan- at Hoxa9 binding sites. sion and is commonly deregulated in human acute leukemias. A C/EBPα is a basic leucine-zipper transcription factor that plays variety of upstream genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia a critical role in lineage commitment during hematopoietic dif- −/− (AML) lead to overexpression of HOXA9, almost always in associ- ferentiation (18). Whereas Cebpa mice show complete loss of ation with overexpression of its cofactor meis homeobox 1 (MEIS1). the granulocytic compartment, recent work shows that loss of α A wide range of data suggests that HOXA9 and MEIS1 play a syn- C/EBP in adult HSCs leads to both an increase in the number ergistic causative role in AML, although the molecular mechanisms of functional HSCs and an increase in their proliferative and leading to transformation by HOXA9 and MEIS1 remain elusive. In repopulating capacity (19, 20). Conversely, CEBPA overexpression can promote transdifferentiation of a variety of fibroblastic cells to this study, we identify CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/ the myeloid lineage and can induce monocytic differentiation in EBPα) as a critical collaborator required for Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated α MLL-fusion protein-mediated leukemias (21, 22). -

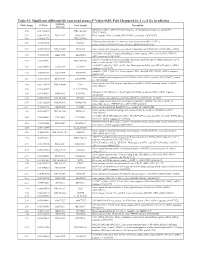

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Test Summary Flyer-NGS Panels.Pub

Cancer‐related Mutaon Analysis Next Generaon Gene Sequencing for Myeloid Tesng Assay Summary IU Health Molecular Pathology Laboratory now offers high throughput sequencing for hot spot mutations found in clinically relevant cancer genes. In addition to a general panel of 54 genes, selected panels have been developed for a more tai- lored application in specific cancers. Comparing to single gene assay, these panels offer a more comprehensive and eco- nomic way to assess prognosis and/or treatment options for cancer patients at the initial diagnosis or at the relapse. Orderable Name: Use IU Health Molecular Pathology requisition; Call 317.491.6417 for requisition. Panels include: AML Mutations by NGS ASXL1, CEBPA, DNMT3A, ETV6/TEL, FLT3, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MLL, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, RUNX1, TET2, TP53, WT1 MDS Mutations by NGS ASXL1, ATRX, BCOR, BCORL1, ETV6/TEL, DNMT3A, EZH2, GNAS, IDH1, IDH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, ZRSR2 CML Mutations by NGS ABL1 MPN Mutations by NGS ASXL1, BRAF, CALR, CSF3R, EZH2, IKZF1, JAK2, JAK3, KDM6A, KIT, MPL, PDGRA, SETBP1, TET2 CMML Mutations by NGS ASXL1, CBL, CBLB, CBLC, EZH2, RUNX1, TET2, TP53, SRSF2 JMML Mutations by NGS CBL, CBLB, CBLC, HRAS, KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11 ALL Mutations by NGS ABL1, CSF3R, FBXW7, IKZF1, JAK3, KDM6A, NOTCH1 CLL Mutations by NGS MYD88, NOTCH1, SF3B1, TP53 Lymphoma/Myeloma Mutations by NGS BRAF, CDKN2A, CSF3R, FBXW7, HRAS, KRAS, MYD88, NOTCH1, NRAS, SF3B1,TP53 Hematopoietic Neoplasms Mutations by NGS ABL1, ASXL1, ATRX, BCOR, BCORL1, BRAF, CALR, CBL, CBLB, CBLC,CDKN2A, CEBPA, CSF3R, CUX1, DNMT3A, ETV6/TEL, EZH2, FBXW7, FLT3, GATA1, GATA2, GNAS, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, IKZF1,JAK2, JAK3, KDM6A, KIT, KRAS, MLL, MPL, MYD88, NOTCH1, NPM1, NRAS, PDGFRA, PHF6, PTEN, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1,SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC1A, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, WT1, ZRSR2 Clinical Utility: This test is useful for the assessment of prognosis and/or treatment options for cancer patients at the initial diagnosis or at the relapse. -

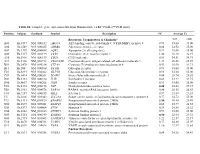

Table S1. Complete Gene Expression Data from Human Diabetes RT² Profiler™ PCR Array Receptors, Transporters & Channels* A

Table S1. Complete gene expression data from Human Diabetes RT² Profiler™ PCR Array Position Unigene GenBank Symbol Description FC Average Ct Receptors, Transporters & Channels* NGT GDM A01 Hs,5447 NM_000352 ABCC8 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 8 0.93 35.00 35.00 A04 0Hs,2549 NM_000025 ADRB3 Adrenergic, beta-3-, receptor 0.88 34.92 35.00 A07 Hs,1307 NM_000486 AQP2 Aquaporin 2 (collecting duct) 0.93 35.00 35.00 A09 30Hs,5117 NM_001123 CCR2 Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 1.00 26.28 26.17 A10 94Hs,5916 396NM_006139 CD28 CD28 molecule 0.81 34.51 34.71 A11 29Hs,5126 NM_001712 CEACAM1 Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 1.31 26.08 25.59 B01 82Hs,2478 NM_005214 CTLA4 (biliaryCytotoxic glycoprotein) T-lymphocyte -associated protein 4 0.53 30.90 31.71 B11 24Hs,208 NM_000160 GCGR Glucagon receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 C01 Hs,3891 NM_002062 GLP1R Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 C07 03Hs,6434 NM_000201 ICAM1 Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 0.84 28.74 28.89 D02 47Hs,5134 NM_000418 IL4R Interleukin 4 receptor 0.64 34.22 34.75 D06 57Hs,4657 NM_000208 INSR Insulin receptor 0.93 35.00 35.00 E05 44Hs,4312 NM_006178 NSF N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor 0.48 28.42 29.37 F08 79Hs,2961 NM_004578 RAB4A RAB4A, member RAS oncogene family 0.88 20.55 20.63 F10 69Hs,7287 NM_000655 SELL Selectin L 0.97 23.89 23.83 F11 56Hs,3806 NM_001042 SLC2A4 Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 4 0.77 34.72 35.00 F12 91Hs,5111 NM_003825 SNAP23 Synaptosomal-associated protein, 23kDa 3.90