Ideological Orientations of the New Left

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

The Rise of Syriza: an Interview with Aristides Baltas

THE RISE OF SYRIZA: AN INTERVIEW WITH ARISTIDES BALTAS This interview with Aristides Baltas, the eminent Greek philosopher who was one of the founders of Syriza and is currently a coordinator of its policy planning committee, was conducted by Leo Panitch with the help of Michalis Spourdalakis in Athens on 29 May 2012, three weeks after Syriza came a close second in the first Greek election of 6 May, and just three days before the party’s platform was to be revealed for the second election of 17 June. Leo Panitch (LP): Can we begin with the question of what is distinctive about Syriza in terms of socialist strategy today? Aristides Baltas (AB): I think that independently of everything else, what’s happening in Greece does have a bearing on socialist strategy, which is not possible to discuss during the electoral campaign, but which will present issues that we’re going to face after the elections, no matter how the elections turn out. We haven’t had the opportunity to discuss this, because we are doing so many diverse things that we look like a chicken running around with its head cut off. But this is precisely why I first want to step back to 2008, when through an interesting procedure, Synaspismos, the main party in the Syriza coalition, formulated the main elements of the programme in a book of over 300 pages. The polls were showing that Syriza was growing in popularity (indeed we reached over 15 per cent in voting intentions that year), and there was a big pressure on us at that time, as we kept hearing: ‘you don’t have a programme; we don’t know who you are; we don’t know what you’re saying’. -

Balkanologie, Vol. 15 N° 2 | 2020 the Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’S “One of Five Million” Pr

Balkanologie Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires Vol. 15 n° 2 | 2020 Pour une approche socio-historique de l'action collective dans les Balkans The Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’s “One of Five Million” Protests Le rôle et le positionnement de la Gauche dans le mouvement « Un sur cinq millions » en Serbie Jelena Pešić and Jelisaveta Petrović Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/2576 DOI: 10.4000/balkanologie.2576 ISSN: 1965-0582 Publisher Association française d'études sur les Balkans (Afebalk) Electronic reference Jelena Pešić and Jelisaveta Petrović, “The Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’s “One of Five Million” Protests ”, Balkanologie [Online], Vol. 15 n° 2 | 2020, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 22 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/2576 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.2576 This text was automatically generated on 22 April 2021. © Tous droits réservés The Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’s “One of Five Million” Pr... 1 The Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’s “One of Five Million” Protests Le rôle et le positionnement de la Gauche dans le mouvement « Un sur cinq millions » en Serbie Jelena Pešić and Jelisaveta Petrović 1 The Great Recession (2008) provoked a series of demonstrations around the globe. In many countries of the European Union (EU), protests initiated by the Institutional Left and various autonomous actors manifested as a synergy of anti-austerity and pro- democracy demands. A significant change in the political and economic landscape, especially in those countries heavily affected by the financial crisis, opened a window of opportunity for greater public receptiveness to critiques of neoliberal capitalism. -

English Translations) Miners to Get Another Master in in the Labor Movement, Has Given and a Cross Petition Has Been 17 Uprising

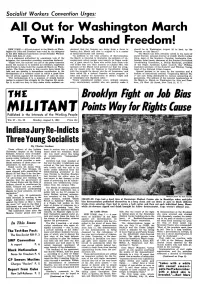

Socialist Workers Convention Urges: All Out for Washington March To Win Jobs and Freedom! NEW YORK — All-out support to the March on Wash derstand that the Negroes are doing them a favor in should be in Washington August 28 to back up the ington for Jobs and Freedom was voted by the delegates leading this March and that to support it is a matter Negroes on this March.” to the 20th National Convention of the Socialist Workers of bread-and-butter self interest. The March has been officially called in the name Of Party held here in July. “In addition to the vital problem of discrimination, James Farmer, national director of CORE; Martin Luther In a statement authorized by unanimous vote of the the March is intended to dramatize the problem of un King, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Con delegates, the convention presiding committee declared: employment which weighs most heavily on Negro work ference; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent “Right now, the number one job of the party branches ers. A giant march by those who suffer from these evils Coordinating Committee; A. Phillip Randolph, president across the country is to mobilize all members, supporters w ill strike fear into their enemies on Capitol Hill. The of the Negro American Labor Council; Roy Wilkins, and friends to help build the August 28 March on Wash sponsors of the March have pointed out that the strug executive secretary of the NAACP; and Whitney Young, ington. The Negro people in this country have taken the gle for decent jobs for Negroes is ‘inextricably linked head of the National Urban League. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

The Student Voice, SNCC Newsletter, 1962-1963

- THE STUDE Vol. 3, No. NT 1 Issued by the Student VOI Nonviolent Coordinating CE Committee,197 1/2 Auburn Ave., Atlanta 3, Ga.April, 1962 TALLADEGA PROTESTS I Student Group Moves After Negotiations Fail TALLADEGA, ALA. - Be By Bob Zellner ginning with a march of 400 students and faculty mem TALLADEGA, ALABAMA - bers, Talladega Collegetook The stimulus for leadership a giant step toward freeing and effective social change their city of segregation. at Talladega College is found The march followed fruit in the Social Action Com less negotiation with Talla mittee (SAC) a group found dega Mayor J . L. Hardwick within the framework of the TALLADEGA STUDENTS PROTEST - Talladega College on April 5. The students ask college's Student Govern s tudents s taged a protest march against segregation on ed the Mayor to present plans ment. As the movement at April 6. Joined by some teachers from the school, the stu- 1 for integration of public faci Talladega has grown, the dents paraded around the Talladega Courthouse bearing lities in the city, and when concept that every student signs reading "We Want Open Libraries" - We Want Equal no plan was forthcoming, the at the college is a member Opportunity." Social Action Committee Chairman Dorothy group marched in protest. of SAC has grown also, and Vails is on the right, above, being inte rviewed by a re- The march was peaceful, and the original smaller com porter. Photo by Zellner. Mayor Hardwick praised the mittee is thought of a plan students and the Talledega ning group. SNCC Con-ference Slated I community for their c alm- Dorothy Vails, a native of J ness. -

Selected Chronology of Political Protests and Events in Lawrence

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY OF POLITICAL PROTESTS AND EVENTS IN LAWRENCE 1960-1973 By Clark H. Coan January 1, 2001 LAV1tRE ~\JCE~ ~')lJ~3lj(~ ~~JGR§~~Frlt 707 Vf~ f·1~J1()NT .STFie~:T LA1JVi~f:NCE! i(At.. lSAG GG044 INTRODUCTION Civil Rights & Black Power Movements. Lawrence, the Free State or anti-slavery capital of Kansas during Bleeding Kansas, was dubbed the "Cradle of Liberty" by Abraham Lincoln. Partly due to this reputation, a vibrant Black community developed in the town in the years following the Civil War. White Lawrencians were fairly tolerant of Black people during this period, though three Black men were lynched from the Kaw River Bridge in 1882 during an economic depression in Lawrence. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1894 that "separate but equal" was constitutional, racial attitudes hardened. Gradually Jim Crow segregation was instituted in the former bastion of freedom with many facilities becoming segregated around the time Black Poet Laureate Langston Hughes lived in the dty-asa child. Then in the 1920s a Ku Klux Klan rally with a burning cross was attended by 2,000 hooded participants near Centennial Park. Racial discrimination subsequently became rampant and segregation solidified. Change was in the air after World "vV ar II. The Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD) formed in 1945 and was in the vanguard of Post-war efforts to end racial segregation and discrimination. This was a bi-racial group composed of many KU faculty and Lawrence residents. A chapter of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) formed in Lawrence in 1947 and on April 15 of the following year, 25 members held a sit-in at Brick's Cafe to force it to serve everyone equally. -

Student Protest Movements at University of Cape Town and University of California-Berkeley from 1960-1965 Brianna White [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wellesley College Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2015 A Cross-Cultural Study: Student Protest Movements at University of Cape Town and University of California-Berkeley from 1960-1965 Brianna White [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation White, Brianna, "A Cross-Cultural Study: Student Protest Movements at University of Cape Town and University of California- Berkeley from 1960-1965" (2015). Honors Thesis Collection. 252. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/252 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cross-Cultural Study: Student Protest Movements at University of Cape Town and University of California-Berkeley from 1960-1965 Brianna White Department of American Studies [email protected] 1 Acknowledgements The student would like to thank my committee of advisors, including Dr. Michael Jeffries, Dr. Barbara Beatty, and Dr. Paul MacDonald. Thank you for your support and patience as I worked to solidify my ideas. I appreciate your feedback and understanding. I would also like to thank the Department of American Studies and Wellesley College for allowing me to pursue this project. Finally I would like to thank my parents and friends for their support. 2 Table of Contents Chapter I: University of Cape Town and University of California- Berkeley: A Comparative Study ........................................................... -

The New Tendency, Autonomist Marxism, and Rank-And-File Organizing in Windsor, Ontario During the 1970S

STRUGGLING FOR A NEW LEFT: THE NEW TENDENCY, AUTONOMIST MARXISM, AND RANK-AND-FILE ORGANIZING IN WINDSOR, ONTARIO DURING THE 1970S A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Sean Antaya 2018 Canadian Studies and Indigenous Studies M.A. Graduate Program September 2018 ABSTRACT Thesis Title: Struggling for a New Left: The New Tendency, Autonomist Marxism, and Rank- and-File Organizing in Windsor, Ontario during the 1970s Author’s Name: Sean Antaya Summary: This study examines the emergence of the New Left organization, The New Tendency, in Windsor, Ontario during the 1970s. The New Tendency, which developed in a number of Ontario cities, represents one articulation of the Canadian New Left’s turn towards working-class organizing in the early 1970s after the student movement’s dissolution in the late 1960s. Influenced by dissident Marxist theorists associated with the Johnson-Forest Tendency and Italian workerism, The New Tendency sought to create alternative forms of working-class organizing that existed outside of, and often in direct opposition to, both the mainstream labour movement and Old Left organizations such as the Communist Party and the New Democratic Party. After examining the roots of the organization and the important legacies of class struggle in Windsor, the thesis explores how The New Tendency contributed to working-class self activity on the shop-floor of Windsor’s auto factories and in the community more broadly. However, this New Left mobilization was also hampered by inner-group sectarianism and a rapidly changing economic context. -

Tom Kahn and the Fight for Democracy: a Political Portrait and Personal Recollection

Tom Kahn and the Fight for Democracy: A Political Portrait and Personal Recollection Rachelle Horowitz Editor’s Note: The names of Tom Kahn and Rachelle Horowitz should be better known than they are. Civil rights leader John Lewis certainly knew them. Recalling how the 1963 March on Washington was organised he said, ‘I remember this young lady, Rachelle Horowitz, who worked under Bayard [Rustin], and Rachelle, you could call her at three o'clock in the morning, and say, "Rachelle, how many buses are coming from New York? How many trains coming out of the south? How many buses coming from Philadelphia? How many planes coming from California?" and she could tell you because Rachelle Horowitz and Bayard Rustin worked so closely together. They put that thing together.’ There were compensations, though. Activist Joyce Ladner, who shared Rachelle Horowitz's one bedroom apartment that summer, recalled, ‘There were nights when I came in from the office exhausted and ready to sleep on the sofa, only to find that I had to wait until Bobby Dylan finished playing his guitar and trying out new songs he was working on before I could claim my bed.’ Tom Kahn also played a major role in organising the March on Washington, not least in writing (and rewriting) some of the speeches delivered that day, including A. Philip Randolph’s. When he died in 1992 Kahn was praised by the Social Democrats USA as ‘an incandescent writer, organizational Houdini, and guiding spirit of America's Social Democratic community for over 30 years.’ This account of his life was written by his comrade and friend in 2005. -

SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos

Transnational networking and cooperation among neo-reformist left parties in Southern Europe during the Eurozone crisis: SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos Vladimir Bortun The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. March 2019 Abstract European parties to the left of social democracy have always lagged behind the main political families in terms of transnational cooperation at the level of the EU. However, the markedly transnational character of the Eurozone crisis and of the management of that crisis has arguably provided a uniquely propitious context for these parties to reduce that gap. This research project aims to establish whether they achieved that by focusing on three parties that were particularly prone to seeking an increase in their transnational cooperation: SYRIZA from Greece, Bloco de Esquerda from Portugal and Podemos from Spain. For these parties not only come from the member states most affected by the crisis, both economically and politically, but they also share several programmatic and strategic features favouring such an increase. By using a mix of document analysis, semi-structured interviews and non-participatory observation, the thesis discusses both the informal and formal transnational networking and cooperation among the three parties. This discussion reveals four key findings, with potentially useful insights for wider transnational party cooperation that are to be pursued in future research. Firstly, the transnational networking and cooperation among SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos did increase at some point during the crisis, particularly around SYRIZA’s electoral victory in January 2015. Secondly, since the U-turn of that government in July 2015, SYRIZA’s relationship with both Bloco and Podemos has declined significantly, as reflected in their diverging views of the EU. -

Berkeley-In-The-60S-Transcript.Pdf

l..J:J __J -- '-' ... BERKELEY IN THE SIXITES Transcript House n-American Activities Committee Demonstration, May 196(J (Music. "Ke a Knockin") T Narrator: y In the 1960s y generation set out on a journey of change. Coming out of an atmosphere f conformity a new spirit began to appear. One of the first signs was a demo tration, organized by Berkeley students in May of 1960 against .;')~u.P -'- the House -American Activities Committee. Archival/Co gressman Willis, HUAC Chairman: \ ' .., iJ' ,o-, «\' What we are ere to do is to gather information as we are ordered to by an act of Congress ith respect to the general operation of the communist conspiracy. Chairman W lis (off camera): Proceed to th next question. Archival/Un entified Witness: I'm not in the habit of being intimidated and I don't expect to start now. Now what was yo_ question? "{/\Thatwas your question. C Lawyer (off camera): Are you now n this instant a member of the communist party. BITS TRAN RIPT 2 t,...J-,,i._l-.. } 'Li..- Narrator: We came out 0 protest because we were against HUAC's suppression of political free m. In the 50s HUAC created a climate of fear by putting people on trial for t ir political beliefs. Any views left of center were labeled subversive. e refused to go back to McCarthyism. Archival/Wi liam Mandel: )/",'; 0 ~ If you think am going to cooperate with this collection of Judases, of men who sit ther in violation of the United States Constitution, if you think I will cooperat with you in any way, you are insane.