00 Dubey 01.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Page 1 of 14 AHIMSA TIMES

AHIMSA TIMES - JANUARY 2009 ISSUE - www.jainsamaj.org Page 1 of 14 Vol. No. 103 Print "Ahimsa Times " January, 2009 www.jainsamaj.org Board of Trustees Circulation + 80000 Copies( Jains Only ) Email: Ahimsa Foundation [email protected] New Matrimonial New Members Business Directory NEW YEAR'S MESSAGE FROM ACHARYA MAHAPRAGYA We Welcome New Year, People visit their places of worship, pray for blessings and desire for success. Next day one forgets it all. The year hands over its legacy, knowledge to the subsequent year. Few of the experiences and knowledge learnt are enormous while others may not be. It is definitely a matter of satisfaction that the general awareness of environmental issues has increased. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that lot more is to be done to protect our eco system from pollution. It is heartening to see people becoming more vigilant against increased menace of violence and terror. Huge time is being spent on deliberation in resolving these issues, which requires fast and prompt action. On the auspicious occasion of the New Year, I am happy to share with you that we are transforming "Ahimsa Yatra" (Journey of Non - violence) program into "Ahimsa Samavaay" (Joint efforts for Non - violence), which is based on seven cardinal principles - a) Development of balanced personality through Ahimsa. b) Solving the family dilemma through Ahimsa. c) Solving the caste and communal problems through Ahimsa. d) To undertake efforts for making the concept of "Economics of Ahimsa" more wide spread & extensive. e) Extension of Ahimsa in the international world through "Ahimsa Universal". -

On Corresponding Sanskrit Words for the Prakrit Term Posaha: with Special Reference to Śrāvakācāra Texts

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 13, No. 2 (2017) 1-17 ON CORRESPONDING SANSKRIT WORDS FOR THE PRAKRIT TERM POSAHA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO ŚRĀVAKĀCĀRA TEXTS Kazuyoshi Hotta 1. Introduction In Brahmanism, the upavasathá purification rite has been practiced on the day prior to the performance of a Vedic ritual. We can find descriptions of this purification rite in Brahmanical texts, such as ŚBr 1.1.1.7, which states as follows. For assuredly, (he argued,) the gods see through the mind of man; they know that, when he enters on this vow, he means to sacrifice to them the next morning. Therefore all the gods betake themselves to his house, and abide by (him or the fires, upa-vas) in his house; whence this (day) is called upa-vasatha (Tr. Eggeling 1882: 4f.).1 This rite was then incorporated into Jainism and Buddhism in different ways, where it is known under names such as posaha or uposatha in Prakrit and Pāli. Buddhism adopted and developed the rite mainly as a ritual for mendicants. Many descriptions of this rite can be found in Buddhist vinaya texts. Furthermore, this rite is practiced until today throughout Buddhist Asia. On the other hand, Jainism has employed the rite mainly as a practice for the laity. Therefore, descriptions of Jain posaha are found in the group of texts called Śrāvakācāra, which contain the code of conduct for the laity. There are many forms of Śrāvakācāra texts. Some are independent texts, while others form part of larger works. Many of them consist mainly of the twelve vrata (restraints) and eleven pratimā (stages of renunciation) that should be observed by * This paper is an expanded version of Hotta 2014 and the contents of a paper delivered at the 19th Jaina Studies Workshop, “Jainism and Buddhism” (18 March 2017, SOAS). -

Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1, December 1999 Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas FUJINAGA Sin Sometimes different philosophers in the same traditiion share the same name. For example, Dr. E. Frauwallner points out that there are two Buddhist philosophers who bear the name Vasubandu." Both of these philosophers are believed to have written important works that are attributed to that name. A similar situation can sometimes be found in the Jaina tradition, and sometimes the situation arises even when the philosophers are in different traditions. For exam- ple, there are two Indian philosophers who are called Haribhadra, one in the Jain tradition, and one in the Buddhist tradition. This paper will argue that one philosopher named Siddhasena, the author of the famous Jaina work, the Sammatitarka, should be distinguished from another philosopher with the same name, the author of the Nvavavatara, a work which occupies an equally important position in Jaina philosophy- 2) One reason to argue that the authors of these works are two different persons is that the works are written in two different languages : the Sammatitarka in Prakrit ; the Nvavavatara in Sanskrit. In the Jaina tradition, it is extremely unusual for the same author to write philosophical works in different languages, the usual languages being either Prakrit or Sanskrit, but not both. Of course, the possibility of one author using two languages cannot be completely eliminated. For example, the Jaina philosopher Haribhadra uses both Prakrit and Sanskrit. But even Haribhadra limits himself to one language when writing a philosophical .work : his philosophical works are all written in Sanskrit, and he uses Prakrit for all of his non-philosophical works. -

Download File (Pdf; 349Kb)

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 9, No. 2 (2013) 1-47 A NEGLECTED ŚVETĀMBARA NARRATIVE COLLECTION HEMACANDRASŪRI MALADHĀRIN'S UPADEŚAMĀLĀSVOPAJÑAVṚTTI PART 1 (WITH AN APPENDIX ON THE FUNERAL OF ABHAYADEVASŪRI MALADHĀRIN) Paul Dundas Scholarly investigation into processes of canonisation in religious traditions has reached such a level of productivity in recent years that it may soon be necessary to establish a canon of outstanding works which discuss the formation of scriptural canons. Research on Jainism has readily acknowledged the interest of this subject, and valuable insights have been gained into the rationales informing the groupings and listings of constituent texts of a variety of Śvetāmbara canons which were introduced from around the middle of the first millennium CE and remained operative into modern times. 1 Also of great value has been the identification of practical canons, effectively curricula or syllabi of texts taken from a range of genres and historical contexts, which have provided modern Śvetāmbara renunciants and laypeople with a framework for gaining an informed understanding of the main parameters of Jain doctrine and practice of most direct concern to them. 2 The historian of Śvetāmbara Jainism has an obvious obligation to be sensitive to the significance of established 'insider' versions of canons. Nonetheless, further possibilities remain for identifying informal Śvetāmbara textual groupings which would not readily fall under the standard canonical rubric of 'scriptural' or 'doctrinal'. In this respect I would consider as at least quasi-canonical the group of major Prakrit and Sanskrit novels or romances ( kathā / kahā ) highlighted by Christine Chojnacki, most notably Uddyotanasūri's Kuvalayamālā and Siddharṣi's Upamitibhavaprapañcakathā, which were written between the seventh and twelfth centuries and whose status was confirmed by their being subsequently epitomised in summary form in the thirteenth century. -

July 2016 Final Pages for Web Edition.Pmd

Regd. With Registrar of Newspaper for India No. MAHBIL/2013/50453 ISSN 2454--7697 `¡É¥ÉÖu Y´É{É' NÉÖWùÉlÉÒ-+ÅOÉàY ´ÉºÉÇ : 4 (HÖ±É ´ÉºÉÇ 64) +ÅH : 4 WÖ±ÉÉ> 2016 Ê´ÉJ©É »ÉÅ´ÉlÉ 2072 ´ÉÒù »ÉÅ´ÉlÉ 2542 +ºÉÉh »ÉÖq ÊlÉÊoÉ 12 • • • ¸ÉÒ ©ÉÖÅ¥É> Wä{É «ÉÖ´ÉH »ÉÅPÉ ~ÉÊmÉHÉ • • • (¡ÉÉùÅ§É »É{É 1929oÉÒ) • • ´ÉÉʺÉÇH ±É´ÉÉW©É °É.200/- • • • • UÚ÷H {ÉH±É °É. 20/- • • ©ÉÉ{Éq lÉÅmÉÒ : eÉè. »ÉàW±É ¶Éɾ XlÉ»ÉÅ´ÉÉq XlÉ©ÉÅoÉ{É »ÉÉoÉà HÉà> ¥ÉÉ¥ÉlÉ{ÉÖÅ »ÉÉäoÉÒ ´ÉyÉÖ ©É¾n´É ¾Éà«É lÉÉà lÉà Uà +Él©É»É{©ÉÉ{É{ÉÒ ùKÉÉ HùÉà +{Éà ¥ÉÒX{ÉÉ +Él©É»É{©ÉÉ{É ~Éù HqÒ XlÉ»ÉÅ´ÉÉq. XlÉ »ÉÉoÉà{ÉÉà »ÉÅ´ÉÉq. +à ©É{ÉÖº«É{ÉÉà ¸Éàºc »ÉÅ´ÉÉq NÉiÉÒ +ÊlÉJ©ÉiÉ {É HùÉà. ~Éù©É ¶ÉÉÅlÉ ¥É{ÉÉà; ~ÉùÅlÉÖ V«ÉÉÅ W°ù ¾Éà«É l«ÉÉÅ ¶ÉHÉ«É. NÉ«ÉÉ +ÅH©ÉÉÅ XlÉ©ÉÅoÉ{É{ÉÒ ´ÉÉlÉ HùÒ +{Éà +ÉWà £ùÒ +à lÉ©ÉÉùÉ ¾ä«ÉÉ{Éà HdiÉ ¥É{ÉÉ´ÉÒ qÉà.' Êq¶ÉÉ©ÉÉÅ oÉÉàeÒ ´ÉÉlÉ Hù´ÉÒ Uà HÉùiÉ +É ©ÉÅoÉ{É »ÉÅ´ÉÉq lÉù£ qÉàùÒ NÉ«ÉÖÅ Hà÷±ÉÒ ©ÉÉà÷Ò ´ÉÉlÉ Uà! »É¾ÖoÉÒ ~ɾà±ÉÉÅ +É~ÉiÉà +É~ÉiÉÒ XlÉ{Éà W Uà. XlÉ »ÉÉoÉà{ÉÉà »ÉÅ´ÉÉq HqÒ ~ÉÚùÉà oÉlÉÉà W {ÉoÉÒ +{Éà lÉà {É oÉÉ«É l«ÉÉÅ Hà{r»oÉ HùÒ +Él©ÉÊ´ÉHÉ»É Hù´ÉÉ{ÉÉà Uà. ©ÉÉà÷à §ÉÉNÉà +É~ÉiÉà +{«É{Éà »ÉÖyÉÒ +É~ÉiÉÒ SÉàlÉ{ÉÉ Y´ÉÅlÉ Uà +{Éà ©ÉÉ~É´ÉÉ©ÉÉÅ ´«É»lÉ ¾Éà>+à Uà. -

Newsetter July~2017

Mahavirai Namah. JAIN SOCIETY OF TORONTO INC. 48 Rosemeade Avenue, Etobicoke, ON M8Y 3A5 (416) 251-8112 - www.jsotcanada.org July 2017 Community Newsletter Jai Jinendra to all the readers Upcoming Event Day Date Program Description Sunday 16-July-17 Senior Session, Sutra Pathshala and Snatra Pooja Sunday 23-July-17 Regular Pathasala and Samayak Sunday 06-Aug-17 Hindi Pooja Sunday 13-Aug-17 Regular Bhakti Friday 18-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 1 Saturday 19-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 2 Sunday 20-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 3–Mahavir Janam Celebration Monday 21-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 4 Tuesday 22-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 5 Wednesday 23-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 6 Thursday 24-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 7 Friday 25-Aug-17 Paryushan Parva Day 8 – Samvatsari Parva Saturday 26-Aug-17 Tapasvi Parna, Tapasvi Varghoda, Alochana Pad Bhakti Group, Dashalakshani Parva Start. Please click below link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B5n0Vlb4TOzXbFo2d1FLMDQyWmM/view?usp=sharing JAINA CONVENTION 2017: The 19th Biennial Convention of JAINA, the federation of Jain organizations of North America, was held in Edison, NJ (USA) from June 30 to Jul 4, 2017. About 4,000 people were in attendance from USA, Canada, India, UK etc. It encompassed various entertainment programs, spiritual discourses, kids program, motivational speeches, Jain Milan events, YJA (Young Jain Association) etc. The Federation of Jain Associations in North America, JAINA is an umbrella organization that includes 68 Jain Centres including Jain temples, sanghs, societies and centers. It is an organization “that preserves and shares Jain Dharma and the Jain Way of Life” The lectures and breakout sessions covered six tracks to highlight Jain philosophy and social services: Jainism and science, education, diaspora, quality of life, community, professionals, entrepreneurship, and ecology. -

World Jain Directory Place Request to Add Your Free Listing in World's

Volume : 102 Issue No. : 102 Month : January, 2009 NEW YEAR'S MESSAGE FROM ACHARYA MAHAPRAGYA We Welcome New Year, People visit their places of worship, pray for blessings and desire for success. Next day one forgets it all. The year hands over its legacy, knowledge to the subsequent year. Few of the experiences and knowledge learnt are enormous while others may not be. It is definitely a matter of satisfaction that the general awareness of environmental issues has increased. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that lot more is to be done to protect our eco system from pollution. It is heartening to see people becoming more vigilant against increased menace of violence and terror. Huge time is being spent on deliberation in resolving these issues, which requires fast and prompt action. On the auspicious occasion of the New Year, I am happy to share with you that we are transforming "Ahimsa Yatra" (Journey of Non - violence) program into "Ahimsa Samavaay" (Joint efforts for Non - violence), which is based on seven cardinal principles - a) Development of balanced personality through Ahimsa. b) Solving the family dilemma through Ahimsa. c) Solving the caste and communal problems through Ahimsa. d) To undertake efforts for making the concept of "Economics of Ahimsa" more wide spread & extensive. e) Extension of Ahimsa in the international world through "Ahimsa Universal". f) Training in Non - violence. g) Development of life - style based on Ahimsa. World Jain Directory Place request to add your I believe that majority in our world wants to live a peaceful life. -

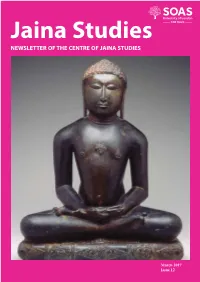

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P. -

Shrimad Rajchandra & Mahatma Gandhi Dr Kumarpal Desai

Shrimad Rajchandra & Mahatma Gandhi Dr Kumarpal Desai ॐ Shrimad Rajchandra & Mahatma Gandhi Author Dr Kumarpal Desai English Translation Raj Saubhag Mumukshus Shree Raj Saubhag Satsang Mandal Near National Highway 8-A, Saubhagpara, Sayla - 363 430 District Surendranagar, Gujarat, India www.rajsaubhag.org Publisher: Publication Committee Shree Raj Saubhag Satsang Mandal Saubhagpara, Sayla - 363 430 Dist Surendranagar, Gujarat, India * All rights reserved for this book by Publication committee Edition : First Edition V. S. 2073 (2017) ISBN: 978-81-935810-0-1 Printer: Pragati Offset Pvt. Ltd. 17, Red hills Hyderabad 500 004, Telangana, India Available at : Shree Raj Saubhag Satsang Mandal Shree Raj Saubhag Ashram, Saubhag Para, Sayla - 363 430. District Surendranagar, Gujarat, India Tel.: +91 2755 280533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.rajsaubhag.org Shree Raj Saubhag Satsang Mandal 34 Shanti Niketan, 5th floor, 95-A Marine Drive, Mumbai 400 002, India Tel: +91 22 2281 3618 Institute of Jainology India B - 101 Samay Apartment, near Azad Society, Ahmedabad 380 015, Gujarat, India Tel: +91 7926762082 Gujarat Vishwakosh Trust Near Rameshpark Society, Near Usmanpura, AUDA Garden Road, Ahmedabad 380 013, India Tel: +91 7927551703 Cost: Rs. 400 Contents 1. Shrimad Rajchandra’s Life Sketch 11 2. Shrimad Rajchandra’s Message 23 3. Shrimad Rajchandra & Mahatma Gandhi 87 4. Three Letters 107 5. Some Memoirs about Shrimad Rajchandra 137 by Gandhiji Mahatma 6. From ‘My Experiments’ with Truth’ 159 7. Discussions on Shrimad Rajchandra by 169 Mahatma Gandhi 8. The Divine Touch of a Pre-eminent Personality 187 9. Shrimad Rajchandra’s Life Timeline 204 10. Shrimad’s Final Poem 207 5 Preface The first meeting between Shrimad Rajchandra and Mahatma Gandhi was an event that will be noted in world history. -

Raj Bhakta Marg: the Path of Devotion to Srimad Rajcandra. a Jain Community in the Twenty First Century

University of Huddersfield Repository Salter, Emma Raj Bhakta Marg: the path of devotion to Srimad Rajcandra. A Jain community in the twenty first century Original Citation Salter, Emma (2002) Raj Bhakta Marg: the path of devotion to Srimad Rajcandra. A Jain community in the twenty first century. Doctoral thesis, University of Wales. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/9211/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ © Emma Salter. Not to be reproduced in any form without the author’s permission Rāj Bhakta Mārg The Path of Devotion to Srimad Rajcandra. A Jain Community in the Twenty First Century. By Emma Salter A thesis submitted in candidature for the degree of doctor of philosophy. University of Wales, Cardiff. -

Jainism Chapter 1

Jainism Chapter 1 Rajesh Kumar Jain M M I G , B - 23, Ram Ganga V i h a r , Phase 2, Extn, M o r a d a b a d - 2 4 4 0 0 1 , UP- B h a r a t . (India) Asia 2013 2014 2015 2016 Copyright © Rajesh Kumar Jain, Moradabad-UP-Bharat. 1 From the Desk of Author Dear Readers:- I am happy to publish first chapter of an English version book Jainism, there was a huge demand from south Bharat, USA and UK, so I tried to write and publish the same. My mother tongue is Hindi, so, there are chances of mistakes and hoping that readers will help to rectify the same. Thanks Rajesh Kumar Jain I wrote my first book in 2013, published on wordpress and BlogSpot, book was listed on Pothi and Chinemonteal in 2014, the second edition was published, listed in 2015 and the language was Hindi. Year wise Readers 2013,2014,2015 25000 21600 20000 15000 Series1 10000 6300 5000 1700 0 1 2 3 2 Month Wise Readers of 2013,2014,2015 3500 N o 3000 2500 o f 2000 1500 Series1 R Series2 e 1000 a 500 Series3 d e 0 r s Month Readers were from 72 USA 13550 countries, list of Top Bharat 9509 eighteen countries are Sweden 3901 given with data. France 552 Germany 250 Taiwan 233 UK 195 European 177 Singapore 107 Japan 70 Russia 64 Canada 46 UAE 46 Indonesia 25 Nepal 23 Australia 22 Malaysia 15 Thailand 15 others 800 3 Country wise Readers at a Glance USA Bharat Sweden France Germany Taiwan UK European Singapore Japan Russia Canada UAE Indonesia Nepal Australia Malaysia Thailand others Year Readers % Growth 2013 1700 - 2014 6300 85 2015 21600 242 4 Left to Right: My Wife Smt Alka Jain, Me, My Mother Smt Prem Lata Jain Left to Right: My son Er Varun Jain, Me, My mother Smt Prem Lata Jain 5 Left to Right My son Er Rajat Jain, Me, My daughter in Law Er Vartika Jain 6 Mangalam Bhagavan viro, Mangalam gautamo gani, Mangalam kundakundadya, Jain dharmostu mangalam.