Caste Hierarchy and New Agro-Technological Practices: Some Anthropological Thoughts on Western Uttar Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate

Volume : 4 | Issue : 6 | June 2015 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Commerce Nimatullahi Sufism and Deccan Bahmani Sultanate Seyed Mohammad Ph.D. in Sufism and Islamic Mysticism University of Religions and Hadi Torabi Denominations, Qom, Iran The presentresearch paper is aimed to determine the relationship between the Nimatullahi Shiite Sufi dervishes and Bahmani Shiite Sultanate of Deccan which undoubtedly is one of the key factors help to explain the spread of Sufism followed by growth of Shi’ism in South India and in Indian sub-continent. This relationship wasmutual andin addition to Sufism, the Bahmani Sultanate has also benefited from it. Furthermore, the researcher made effortto determine and to discuss the influential factors on this relation and its fruitful results. Moreover, a brief reference to the history of Muslims in India which ABSTRACT seems necessary is presented. KEYWORDS Nimatullahi Sufism, Deccan Bahmani Sultanate, Shiite Muslim, India Introduction: are attributable the presence of Iranian Ascetics in Kalkot and Islamic culture has entered in two ways and in different eras Kollam Ports. (Battuta 575) However, one of the major and in the Indian subcontinent. One of them was the gradual ar- important factors that influence the development of Sufism in rival of the Muslims aroundeighth century in the region and the subcontinent was the Shiite rule of Bahmani Sultanate in perhaps the Muslim merchants came from southern and west- Deccan which is discussed briefly in this research paper. ern Coast of Malabar and Cambaya Bay in India who spread Islamic culture in Gujarat and the Deccan regions and they can Discussion: be considered asthe pioneers of this movement. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 27, No. 1, January-June 2012, pp.141-169 Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh Muhammad Sohail University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT The arrival of the Muslims in the sub-continent of Indo-Pakistan was a remarkable incident of the History of sub-continent. It influenced almost all departments of the social life of the people. The Muslims had a marvelous contribution in their culture and civilization including architecture, painting and calligraphy, book-illustration, music and even dancing. The Hindus had no interest in history and biography and Muslims had always taken interest in life-history, biographical literature and political-history. Therefore they had an excellent contribution in this field also. However their most significant contribution is the bestowal of Urdu language. Although the Muslims came to the sub-continent in three capacities, as traders or business men, as commanders and soldiers or conquerors and as Sufis and masha’ikhs who performed the responsibilities of preaching, but the role of the Sufis and mash‘iskhs in the evolving and development of Urdu is the most significant. The objective of this paper is to briefly review their role in this connection. KEY WORDS: Urdu language, Sufia and Mashaikh, India, Culture and civilization, genres of literature Introduction The Muslim entered in India as conquerors with the conquests of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 94 AH / 712 AD. Their arrival caused revolutionary changes in culture, civilization and mode of life of India. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

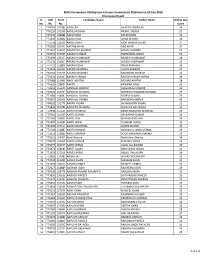

Sl. No. Roll No. Form No. Candidate Name Father Name Online Test

RUHS Paramedical UG/Diploma Entrance Examination 2018 held on 22-July-2018 Provisional Result Sl. Roll Form Candidate Name Father Name Online test No. No. No. Score 1 774709 157580 AADIL ALI AKHTAR JAWED ALI 24 2 776110 152356 AADIL HUSSAIN MOHD. SADDIK 23 3 775335 158688 AADIL KHAN ZAFAR KHAN 30 4 773345 153862 AADIL KHAN ILIYAS AHMED 34 5 775548 158239 AADIL SHEKH MOH ANWAR SHEKH 27 6 770300 150497 AAFTAB KHAN AZIZ KHAN 27 7 771637 154595 AAKANSHA SHARMA KAMAL SHARMA 27 8 774515 157095 AAKASH KUMAR MAHENDRA SINGH 53 9 775699 150357 AAKASH KUMAWAT MUKESH KUMAWAT 28 10 775130 156807 AAKASH KUMAWAT SURESH KUMAWAT 31 11 774711 152808 AAKASH OJHA PREM PRAKASH 33 12 774032 155356 AAKASH SHARMA LALITA SHARMA 19 13 774263 157776 AAKASH SHARMA RAMDHAN SHARMA 20 14 775634 156007 AAKASH VERMA RAJESH KUMAR VERMA 28 15 773588 151461 AAKIF AKHTAR ARSHAD AKHTAR 28 16 776626 158824 AAKRTI KANWAR SINGH 26 17 770659 155640 AANCHAL DINDOR MAGANLAL DINDOR 22 18 775121 154734 AANCHAL SHARMA MAHESH CHANDRA SHARMA 24 19 772086 158087 AANCHAL SUMAN SURESH SUMAN 25 20 775097 150908 AANCHAL VERMA RAJENDRA VERMA 49 21 774632 152376 AARAV YADAV JAI NARAYAN YADAV 23 22 771846 157780 AAROHEE SHARMA Kishan lal loknathaka 30 23 772930 155169 AARTI DHABHAI BADRI NARAYAN DHABHAI 29 24 770741 151563 AARTI GURJAR DEVKARAN GURJAR 24 25 773160 156830 AARTI JAIN BHAGCHAND JAIN 34 26 773407 154289 AARTI JAIPAL TEJARAM JAIPAL 32 27 771420 157114 AARTI MEGHWAL ASHOK KUMAR 31 28 772749 152887 AARTI PANWAR SUBHASH CHAND VERMA 19 29 775073 153889 AARTI SHARMA ROOP NARAYAN SHARMA -

Rajasthan Public Service Commission, Ajmer Rejected

RAJASTHAN PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, AJMER REJECTED CANDIDATES OF VP SUPERINTENDENT ITI EXAM 2012 PG- 1 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ SNO APP_ID NAME FNAME BIRTHDATE CTG ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 970104652588 AASHUTOSH MAHESHWARI GHANSHYAM MAHESHWARI 01/11/1989 GE 2 97011811373 ABDUL JAVED ABDUL GAFFAR 05/06/1977 GE 3 97011793008 ABHILASHA DUBEY L.D. DUBEY 09/06/1989 GE,WE 4 970104650604 ABHISHEK CHATTRI JAGESH KUMAR CHATTRI 18/09/1983 GE 5 970104651787 ABHISHEK CHHAJER ASHOK CHHAJER 21/02/1988 GE 6 970104651054 ABHISHEK GUPTA KEDAR NATH GUPTA 09/02/1990 GE 7 97011788389 ABHISHEK KATARA DEEPAK DHULIYA 10/10/1986 GE 8 97011837163 ABHISHEK KUMAR DR. BHAGWAN SAHAI PAL 08/09/1985 GE,RG 9 97011812086 ABHISHEK KUMAR SHARMA MAHENDRA KUMAR SHARMA 19/10/1981 BC 10 970104652286 ABHISHEK SHARMA VINOD KUMAR SHARMA 12/12/1984 GE 11 970104649158 ABIRAM JHA SRI VINDHYA NATH JHA 15/05/1982 GE,RG,NZ,NG 12 97011786849 AISHWARY JAIN RAJ KUMAR JAIN 21/06/1988 GE 13 970104653084 AJAAYPAL SINGH SAHAB SINGH 26/07/1986 BC 14 970104649869 AJAY KUMAR JAIN SOM CHAND JAIN 20/10/1984 GE 15 97011779711 AJAY KUMAR MISHRA RAMAVTAR MISHRA 02/05/1976 GE 16 97011843591 AJAY MATHUR OM PRAKASH MATHUR 27/11/1985 GE 17 970104650710 AJAY SINGH BAJRANG SINGH 24/04/1992 GE 18 97011814596 AJAY VYAS KAILASH VALLABH VYAS 14/12/1973 GE,RG 19 97011827949 AJAYPAL SINGH PRAHLAD SINGH PARMAR 04/02/1987 -

Lambada- Telugu Contact: Factors Affecting Language Choice in Bilinguals

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 5 Issue 10||October. 2016 || PP.43-46 Lambada- Telugu Contact: Factors Affecting Language Choice in Bilinguals Kishore Vadthya PhD, Applied Linguistics, University of Hyderabad ABSTRACT: Language contact between Lambadi and Telugu in Telangana region has been in effect since before independence. Generations of contact has resulted in bilingualism of various degrees among them. This bilingualism has produced variation in the use of Lambadi language with respect to psychological, social and cultural factors further under the influence of urbanization and globalization. Part of a series of research, addressed to analyze the synchronic effects seen as a consequence of the contact of lambada with a dominant language (culturally and in numbers), this paper aims to state and consolidate all factors influencing the language maintenance and shift among Lambada speakers. Under such circumstances, an analysis of language choice under the influence of factors ranging from situation, topic, domain, role, media as theorized by Fishman(1965) are applicable with furthermore additions resulting from Lambadi being an oral language. Language contact and choice, of two languages with scripts has to be viewed in a different perspective than the contact between an orally passed down language and a language with script. Media variance tips the needle towards the scripted language for all governmental and technical purposes and thus eliminates the resistance to shift from mother tongue which is otherwise universally seen. Similar differences have been studied and an effort to give a construct more suitable to the multilingual contact study of the case under study has been done in this paper. -

Grammatical Gender and Linguistic Complexity

Grammatical gender and linguistic complexity Volume I: General issues and specific studies Edited by Francesca Di Garbo Bruno Olsson Bernhard Wälchli language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 26 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J. (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. 17. Stenzel, Kristine & Bruna Franchetto (eds.). On this and other worlds: Voices from Amazonia. 18. Paggio, Patrizia and Albert Gatt (eds.). The languages of Malta. 19. Seržant, Ilja A. & Alena Witzlack-Makarevich (eds.). Diachrony of differential argument marking. 20. Hölzl, Andreas. A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond: An ecological perspective. 21. Riesberg, Sonja, Asako Shiohara & Atsuko Utsumi (eds.). Perspectives on information structure in Austronesian languages. -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

Introduction

ONE Introduction THE DYNASTIES Sec. 1 The Qutb Shahs On the break up of the Bahmani Kingdom towards the close of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth century there arose in the Deccan five different sultanates. Of these Golconda was one. It was founded by Sultan Quli a member of the Black Sheep (Qara Quyunlu) Tribe 2 During Bahmani rule a number of foreigners from Iran and other places used to migrate to the Decoan which was for them a land of opportunities. Some of the emigrants rose to high position and Sultan Quli by his abilities rose to be the governor (tarafdar) of Tilangana.^ Sultan Quli joined service under Mahmud Shah Bahmani when a conflict between such emigrants (Afaqis) and the native called Deccani people had become deep rooted and hence a decisive factor in power politics of the Deccan. z The Bahmani Sultanate was tottering under the pressure of that conflict. The nobles were maneuvering to break away from the Sultanate and assume autonomy within a jurisdiction under their control. Sultan Quli was no less ambitious and capable of such autonomy than any other noble in the Beccan, Nevertheless he was scrupulous and preferred slow and steady measures to revolution. With a view to maintain his status in the society of states he joined the/^afavi Movement.) That c alliance was essential for the survival of his Sultanate since the other Sultanates of the Deccan like Bijapur and Ahmadnagar 4 had fallen in with the same movement. SULTM QULI Sultan Quli Qu-^b Shah was a disciple of Shah Na'^yimu• ddin 5 Ni'^matullah of Yazd* As the Sufi households of Iran were assuming a Shi'ite character by the close of the fifteenth century Sultan Quli Qutb Shah too adhered to the Shi'ite 6 faith, which subsequently he upheld as a State Religion. -

Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India

Chapter one: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India 1.1 Introduction: India also known as Bharat is the seventh largest country covering a land area of 32, 87,263 sq.km. It stretches 3,214 km. from North to South between the extreme latitudes and 2,933 km from East to West between the extreme longitudes. On this 2.4 % of earth‟s surface, lives 16% of world‟s population. With a population of 1,028,737,436 variations is there at every step of life. India is a land of bewildering diversity. India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the Figure 1.1: India in World Population south, the Arabian Sea on the west and the Bay of Bengal on the east. Many outsiders explored India via these routes. The whole of India is divided into twenty eight states and seven union territories. Each state has its own cultural and linguistic peculiarities and diversities. This diversity can be seen in every aspect of Indian life. Whether it is culture, language, script, religion, food, clothing etc. makes ones identity multi-dimensional. Ones identity lies in his language, his culture, caste, state, village etc. So one can say India is a multi-centered nation. Indian multilingualism is unique in itself. It has been rightly said, “Each part of India is a kind of replica of the bigger cultural space called India.” (Singh U. N, 2009). Also multilingualism in India is not considered a barrier but a boon. 17 Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India Languages act as bridges because it enables us to know about others. -

Aryan and Non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the Linguistic Situation, C

Michael Witzel, Harvard University Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.. § 1. Introduction To describe and interpret the linguistic situation in Northern India1 in the second and the early first millennium B.C. is a difficult undertaking. We cannot yet read and interpret the Indus script with any degree of certainty, and we do not even know the language(s) underlying these inscriptions. Consequently, we can use only data from * archaeology, which provides, by now, a host of data; however, they are often ambiguous as to the social and, by their very nature, as to the linguistic nature of their bearers; * testimony of the Vedic texts , which are restricted, for the most part, to just one of the several groups of people that inhabited Northern India. But it is precisely the linguistic facts which often provide the only independent measure to localize and date the texts; * the testimony of the languages that have been spoken in South Asia for the past four thousand years and have left traces in the older texts. Apart from Vedic Skt., such sources are scarce for the older periods, i.e. the 2 millennia B.C. However, scholarly attention is too much focused on the early Vedic texts and on archaeology. Early Buddhist sources from the end of the first millennium B.C., as well as early Jaina sources and the Epics (with still undetermined dates of their various strata) must be compared as well, though with caution. The amount of attention paid to Vedic Skt.