Fictional Characters and Their Discontents: a Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics of Fictional Entities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Existentialism of Martin Buber and Implications for Education

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-4919 KINER, Edward David, 1939- THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Education, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE EXISTENTIALISM OF MARTIN BUBER AND IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward David Kiner, B.A., M.A. ####*### The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Adviser College of Education This thesis is dedicated to significant others, to warm, vital, concerned people Who have meant much to me and have helped me achieve my self, To people whose lives and beings have manifested "glimpses" of the Eternal Thou, To my wife, Sharyn, and my children, Seth and Debra. VITA February 14* 1939 Born - Cleveland, Ohio 1961......... B.A. Western Reserve University April, 1965..... M.A. Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion June, 1965...... Ordained a Rabbi 1965-1968........ Assistant Rabbi, Temple Israel, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1968...... Director of Religious Education, Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Philosophy of Education Studies in Philosophy of Education, Dr. Everett J. Kircher Studies in Curriculum, Dr. Alexander Frazier Studies in Philosophy, Dr. Marvin Fox ill TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION............................................. ii VITA ................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................ 1 Chapter I. AN INTRODUCTION TO MARTIN BUBER'S THOUGHT....... 6 Philosophical Anthropology I And Thou Martin Buber and Hasidism Buber and Existentialism Conclusion II. EPISTEMOLOGY . 30 Truth Past and Present I-It Knowledge Thinking Philosophy I-Thou Knowledge Complemented by I-It Living Truth Buber as an Ebdstentialist-Intuitionist Implications for Education A Major Problem Education, Inclusion, and the Problem of Criterion Conclusion III. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

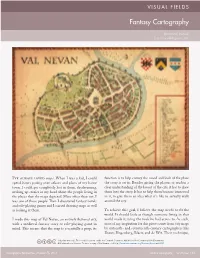

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Karl Polanyi. Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker. (Ebook / PDF)

BRIGITTE AULENBACHER, MARKUS MARTERBAUER, ANDREAS NOVY, KARI POLANYI LEVITT, ARMIN THURNHER (EDS.) KARL POLANYI The Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker Karl Polanyi BRIGITTE AULENBACHER, MARKUS MARTERBAUER, ANDREAS NOVY, KARI POLANYI LEVITT, ARMIN THURNHER (EDS.) KARL POLANYI The Life and Works of an Epochal Thinker Translated by Jan-Peter Herrmann and Carla Welch FALTERVERLAG The translation has been funded by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. ISBN 978-3-85439-689-5 © 2020 Falter Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H. 1011 Wien, Marc-Aurel-Straße 9 T: +43/1/536 60-0, F: +43/1/536 60-935 E: [email protected], [email protected] W: faltershop.at All rights reserved. Editors: Brigitte Aulenbacher, Markus Marterbauer, Andreas Novy, Kari Polanyi Levitt, Armin Thurnher Translator: Jan-Peter Herrmann, Carla Welch Illustrations: P.M. Hoffmann Layout: Marion Großschädl Production: Susanne Schwameis Printed by myMorawa With this book, we care about the packaging dispensed with plastic wrap. Table of ConTenT Brigitte Aulenbacher, Andreas Novy: Acknowledgements 7 Marguerite Mendell: Foreword 9 Armin Thurnher: Foreword of the German edition 12 I. The Renaissance Brigitte Aulenbacher, Veronika Heimerl, Andreas Novy: The Limits of a Market Society 17 Armin Thurnher: ‘Many graze on Polanyi’s pasture’ 24 Michael Burawoy: Fictitious Commodities and the Three Waves of Marketization 33 II. The Personal and the Historical Michael Burawoy: ‘Wherever my father lived he was engaged in whatever was going on’. Shaping The Great Transformation: a conversation with Kari Polanyi Levitt 41 Michael Brie, Claus Thomasberger: Freedom in a Threatened Society 53 Veronika Helfert: Born a Rebel, Always a Rebel 61 Andreas Novy: From Development Economist to Trailblazer of the Polanyi Renaissance 66 Franz Tödtling: From Physical Chemistry to the Philosophy of Knowledge 74 Michael Mesch: Milieus in Karl Polanyi’s Life 82 Gareth Dale: Karl Polanyi in Budapest 94 Robert Kuttner: Karl Polanyi and the Legacy of Red Vienna 98 Sabine Lichtenberger: ‘The Earliest Beginnings of His Later Teaching Life’ 101 III. -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International). -

Fictional Names and Fictional Discourse

Fictional names and fictional discourse Chiara Panizza ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

Disagreeing About Fiction

Préparée à Institut Jean Nicod, UMR 8129 Disagreeing about fiction Soutenue par Composition du jury : Louis ROUILLÉ Stacie Friend Le 02 12 2019 Senior Lecturer in Philosophy, Birkbeck, Présidente University of London Françoise Lavocat Professeure de littérature comparée, Uni- Rapportrice o versité Paris 3-Sorbonne nouvelle École doctorale n 540 Emar Maier Lettres, Arts, Sciences Assistant Professor Philosophy & Linguis- Rapporteur tics, University of Groningen humaines et sociales Anne Reboul Directrice de recherche au CNRS, Institut Examinatrice Marc Jeannerod, UMR 5304 Paul Égré Spécialité Directeur de recherche au CNRS, Institut Directeur de thèse Jean Nicod, UMR 8129 Philosophie François Récanati Professeur au Collège de France Directeur de thèse Contents Introduction: Is it really a philosophical problem? 13 Fiction as a metaphilosophical problem.................... 13 Parmenides, the Visitor and Plato’s problem................. 15 The problem of non-being (or the non-problem of being)....... 15 Conceptual reconstruction of Plato’s problem............. 19 Conceptual re-reconstruction.......................... 23 Brentano’s problem and program.................... 23 Brentano’s program............................ 27 The metaphysics of relations....................... 28 Consequences for the problem of fiction................. 30 Content and structure of the dissertation................... 32 I Truth in fiction: towards pretence semantics 35 1 The problem 36 1.1 Description of the problem........................ 36 1.2 Non-starters................................ 38 1.3 Explicitism and Intentionalisms..................... 39 1.3.1 Against explicitism........................ 40 1.3.2 Intentionalisms.......................... 43 1.4 Two incompatible solutions on the market............... 45 1.4.1 The modal account........................ 45 1.4.2 The functional account...................... 46 1.4.3 The two solutions are incompatible............... 47 1.5 Plan of action.............................. -

The Novel Map

The Novel Map The Novel Map Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction Patrick M. Bray northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2013 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2013. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Bray, Patrick M. The Novel Map: Space and Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century French Fiction. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2013. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and the earlier version of chapter 4 as outlined in the Author’s Note For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note xiii Introduction Here -

The Balance of Personality

The Balance of Personality The Balance of Personality CHRIS ALLEN PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The Balance of Personality by Chris Allen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. The Balance of Personality Copyright © by Chris Allen is licensed under an Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, except where otherwise noted. Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Front Cover Photo: x Special Thanks to: x Open Educational Resources xi Introduction 1 1. Personality Traits 3 Introduction 3 Facets of Traits (Subtraits) 7 Other Traits Beyond the Five-Factor Model 8 The Person-Situation Debate and Alternatives to the Trait Perspective 10 2. Personality Stability 17 Introduction 18 Defining Different Kinds of Personality Stability 19 The How and Why of Personality Stability and Change: Different Kinds of Interplay Between Individuals 22 and Their Environments Conclusion 25 3. Personality Assessment 30 Introduction 30 Objective Tests 31 Basic Types of Objective Tests 32 Other Ways of Classifying Objective Tests 35 Projective and Implicit Tests 36 Behavioral and Performance Measures 38 Conclusion 39 Vocabulary 39 4. Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, Nancy Chodorow: Viewpoints on Psychodynamic Theory 43 Introduction 43 Core Assumptions of the Psychodynamic Perspective 45 The Evolution of Psychodynamic Theory 46 Nancy Chodorow’s Psychoanalytic Feminism and the Role of Mothering 55 Quiz 60 5. Carl Jung 63 Carl Jung: Analytic Psychology 63 6. Humanistic and Existential Theory: Frankl, Rogers, and Maslow 78 HUMANISTIC AND EXISTENTIAL THEORY: VIKTOR FRANKL, CARL ROGERS, AND ABRAHAM 78 MASLOW Carl Rogers, Humanistic Psychotherapy 85 Vocabulary and Concepts 94 7. -

Dissertation Final

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title LIterature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nj845hz Author Jones, Ruth Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 © Copyright by Ruth Elizabeth Jones 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literature, Representation, and the Image of the Francophone City: Casablanca, Montreal, Marseille by Ruth Elizabeth Jones Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Patrick Coleman, Chair This dissertation is concerned with the construction of the image of the city in twentieth- century Francophone writing that takes as its primary objects the representation of the city in the work of Driss Chraïbi and Abdelkebir Khatibi (Casablanca), Francine Noël (Montreal), and Jean-Claude Izzo (Marseille). The different stylistic iterations of the post Second World War novel offered by these writers, from Khatibi’s experimental autobiography to Izzo’s noir fiction, provide the basis of an analysis of the connections between literary representation and the changing urban environments of Casablanca, Montreal, and Marseille. Relying on planning documents, historical analyses, and urban theory, as well as architectural, political, and literary discourse, to understand the fabric of the cities that surround novels’ representations, the dissertation argues that the perceptual descriptions that enrich these narratives of urban life help to characterize new ways of seeing and knowing the complex spaces of each of the cities. -

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #69

1 82658 00098 1 The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FALL 2016 FALL $10.95 #69 All characters TM & © Simon & Kirby Estates. THE Contents PARTNERS! OPENING SHOT . .2 (watch the company you keep) FOUNDATIONS . .3 (Mr. Scarlet, frankly) ISSUE #69, FALL 2016 C o l l e c t o r START-UPS . .10 (who was Jack’s first partner?) 2016 EISNER AWARDS NOMINEE: BEST COMICS-RELATED PERIODICAL PROSPEAK . .12 (Steve Sherman, Mike Royer, Joe Sinnott, & Lisa Kirby discuss Jack) KIRBY KINETICS . .18 (Kirby + Wood = Evolution) FANSPEAK . .22 (a select group of Kirby fans parse the Marvel settlement) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .29 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) KIRBY OBSCURA . .30 (Kirby sees all!) CLASSICS . .32 (a Timely pair of editors are interviewed) RE-PAIRINGS . .36 (Marvel-ous cover recreations) GALLERY . .39 (some Kirby odd couplings) INPRINT . .49 (packaging Jack) INNERVIEW . .52 (Jack & Roz—partners for life) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .60 (Sandman & Sandy revamped) OPTIKS . .62 (Jack in 3-D Land) SCULPTED . .72 (the Glenn Kolleda incident) JACK F.A.Q.s . .74 (Mark Evanier moderates the 2016 Comic-Con Tribute Panel, with Kevin Eastman, Ray Wyman Jr., Scott Dunbier, and Paul Levine) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .92 (as a former jazz bass player, the editor of this mag was blown away by the Sonny Rollins letter...) PARTING SHOT . .94 (never trust a dwarf with a cannon) Cover inks: JOE SINNOTT from Kirby Unleashed Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Direct from Roz Kirby’s sketchbook, here’s a team of partners that holds a for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps. -

Science and Evolution in the Public Eye

Science and Evolution in the Public Eye Laurie R. Godfrey Many educators have expressed surprise at the extent to which students believe sensationalistic and catastrophic explanations of the origins of cultural and biological traits. Their inclination is to ignore sensationalism as "unworthy" of serious discussion, but they are being hampered by political pressures from the sensationalists, who tend to view themselves as bearers of "true science" and as opponents of outdated scientific beliefs or orthodoxies. Thus these catastrophic and often cryptoscientific views of racial and cultural trait origins are being given increasing exposure in popular literature, on TV, in movies, and in public school and college classrooms. Among the most notorious examples of this alarming trend are von Daniken's Chariots of the Gods? (1970), Barry Fell's America B.C. (1976), Jeffrey Goodman's Psychic Archaeology (1977), the "In Search of TV series, and the current UFO mania. Organizations with blatantly racist motives, such as the Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, who proclaim separate "origins" (or creations) for different "races," are once again growing in visibility. The "orthodoxies" of the anthropological "establishment" are being challenged by students who proclaim separate-origins explanations (a series of invasions from outer space, or "experiments" by a creator) and by some of those proclaiming a single creation. These sensationalist views are financially supported by evangelistic grass-roots organizations. These organizations are politically active in the sense that each is "spreading the word." The various Bible research groups that hold weekly or biweekly meetings on college campuses engage in peculiar mixtures of odd-fact collecting and religious ceremony.