Download Full Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

An Index to Alan Ansen's the Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited By

An Index to Alan Ansen’s The Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited by Nicholas Jenkins Index Compiled by Jacek Niecko A Supplement to The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 20 • June 2000 Jacek Niecko is at work on a volume of conversations and interviews with W. H. Auden. Adams, Donald James 68, 115 Christmas Day 1941 letter to Aeschylus Chester Kallman 105 Oresteia 74 Collected Poems (1976) 103, 105, Akenside, Mark 53 106, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, Amiel, Henri-Frédéric 25 114, 116, 118 Andrewes, Lancelot 75 Collected Poetry 108 Meditations 75 Dark Valley, The 104 Sermons 75 Dog Beneath the Skin, The 51, 112 Aneirin Dyer’s Hand, The xiii, 100, 109, 111 Y Gododdin 108 “Easily, my dear, you move, easily Ann Arbor, Michigan 20, 107 your head” 106 Ansen, Alan ix-xiv, 103, 105, 112, 115, Enemies of a Bishop, The 22, 107 117 English Auden, The 103, 106, 108, Aquinas, Saint Thomas 33, 36 110, 112, 115, 118 Argo 54 Forewords and Afterwords 116 Aristophanes For the Time Being 3, 104 Birds, The 74 Fronny, The 51, 112 Clouds, The 74 “Greeks and Us, The” 116 Frogs, The 74 “Guilty Vicarage, The” 111 Aristotle 33, 75, 84 “Hammerfest” 106 Metaphysics 74 “Happy New Year, A” 118 Physics 74 “I Like It Cold” 115 Arnason Jon “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” xv, 70 Icelandic Legends 1 “In Search of Dracula” 106 Arnold, Matthew xv, 20, 107 “In Sickness and In Health” 106 Asquith, Herbert Henry 108 “In the Year of My Youth” 112 Athens, Greece 100 “Ironic Hero, The” 118 Atlantic 95 Journey to a War 105 Auden, Constance Rosalie Bicknell “Law Like Love” 70, 115 (Auden’s mother) 3, 104 Letter to Lord Byron 55, 103, 106, Auden, Wystan Hugh ix-xv, 19, 51, 99, 112 100, 103-119 “Malverns, The” 52, 112 “A.E. -

CV, Full Format

BENJAMIN PALOFF (1/15/2013) Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures 507 Bruce Street University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Ann Arbor, MI 48103 3040 MLB, 812 E. Washington (617) 953-2650 Ann Arbor, MI 48109 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 2007. M.A. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, November 2002. Dissertation: Intermediacy: A Poetics of Unfreedom in Interwar Russian, Polish, and Czech Literatures, a comparative treatment of metaphysics in Eastern European Modernism, 1918-1945. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan M.F.A. in Creative Writing/Poetry, April 2001. Thesis: Typeface, a manuscript of poems. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts B.A., magna cum laude with highest honors in field, Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 1999. Honors thesis: Divergent Narratives: Affinity and Difference in the Poetry of Zbigniew Herbert and Miroslav Holub, a comparative study. TEACHING Assistant Professor, Departments of Slavic Languages and Literatures and of Comparative Literature, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (2007-Present). Courses in Polish and comparative Slavic literatures, critical theory, and translation. Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Slavic Languages and Literatures: Jessica Zychowicz (Present), Jodi Grieg (Present), Jamie Parsons (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Comparative Literature: Sylwia Ejmont (2008), Corine Tachtiris (2011), Spencer Hawkins (Present), Olga Greco (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in other units: Ksenya Gurshtein (History of Art, 2011). MFA Thesis Committee in English/Creative Writing: Francine Harris (2011). Faculty Associate, Frankel Center for Jewish Studies (2009-Present); Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (2007-Present). Service: Steering Committee, Copernicus Endowment for Polish Studies (2007-Present). -

After Miłosz: Polish Poetry in the 20Th and the 21Th Century Chicago, Chopin Theatre, 9/30 –10/3 2011

After Miłosz: Polish Poetry In the 20th and the 21th Century Chicago, Chopin Theatre, 9/30 –10/3 2011 THE FESTIVAL The Chicago's literary festival titled After Milosz: Polish Poetry in the 20th and 21th Century is the largest presentation of Polish poetry in the United States this year. The festival celebrates the year of Czeslaw Milosz and commemorates the centennial anniversary of the birth of the Nobel Prize winner. The event goes beyond a familiar formula of commenting the work of the poet and offers a broader view on the contemporary Polish poetry. Besides the academic conference dedicated to Milosz's work, and a panel with the greatest America poets (Jorie Graham, Charles Simic) remembering the artist and discussing his influence on American poetry, the program includes readings of the most talented modern Polish poets of three generations. From the best known (Zagajewski, Sommer) to the most often awarded young writer nowadays, Justyna Bargielska. An important part of the festival will be two concerts: the opening show will present the best Polish rappers FISZ and EMADE whose songs are inspired by Polish poetry; another concert will present one of the best jazz singers in the world, Patricia Barber, who will perform especially for this occasion. The main organizers of the festival are the Fundation of Tygodnik Powszechny magazine and the Joseph Conrad International Literary Festival in Krakow, for which the Chicago festival is a portion of the larger international project for promoting Polish literature abroad. The co- organizer of the festival is the Head of the Slavic Department at University of Illinois at Chicago, Professor Michal Pawel Markowski, who represents also the Polish Interdisciplinary Program at UIC supported by The Hejna Fund, and also serves as the artistic director to the Conrad Festival. -

Download Complete Volume

JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF THE - VICTOR I A INSTITUTE. VOL. XXI. SECTION NI;> I FROM SEA. COAST AT A.Sl(A,LA ~ H JERUSAlEM TO THE J,JR~AN IIIC.0 JEHi CH O." t<0~110,n·... lsc"lt3''"'EII -I,,..,;;": C.S. Wlc.Sw,a.~t,n,,,ofl'l,illutin., N. l. Nwri,.wlil,: .l,V,W,,tn,u,, C. l . Crct,rcc,,,,,, J.,,,.,,,.i,,,,..., _ N. 1.:. }Vu.blit.n. Sun.J&/.,)1.,. F. V, £,,1.~1,,,,~. SECTION N'? 2. FRO M T H E. T A.B LE · LANO Of' S ,JUD.EA TOT Mt PLAINS Of'MOA.B ~. oFKtRAH. 8YJEB£L USOUM. TA.SL£ L,.ND or MOAB SECTION N~ 7 !='ROM cuLr o F sun MEAFtTO R eY THE M OUNTAINS o, s 1ttA.1 ro-:-wt: PLAT EAU or TH£ TIH. No rt,h, G. &rcy !Jra..,,,i, t;,e, (F>1.r-i,.t(C11) a.n.d, 5,·'hi.tt. w.:.th. ·m.,,m.flr-OU.4 d.y1<.r f! , • ..,,po.-w,g s,uubto,.,, n,,d.Li,,,... •w,,.-B,:,i,, / S . 8 L j 11flRl20NTALSCALr 11MIL[ S• I INCH. J)y l~o;1nniu,on of th i:J Oommittce (•f the /'o,T,i:sti.1w E :cpluMtivn Fund. JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF ~ht lictoria Jnstitut~, <'lR l!gilosopgital cSotiet~ of ~reat Jritain. EDITED BY THE HONORARY SECRETARY, CAPTAIN FRANCIS W. H. PETRIE, F.G.fS., &c. VOL. XXI. LONDON: (tBublisbell n11 tbe Institute). INDIA: W. THACKER & Co. UNITED STATES: G. T.PUTNAM'S SONS, N.Y_. -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

The Emblematic Imagination of Anthony Hecht Worldly and Religious Icons and Rituals

Master’s Degree in English and American literary studies Final Thesis The Emblematic Imagination of Anthony Hecht Worldly and Religious Icons and Rituals Supervisor Ch. Prof. Gregory Dowling Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Gabriella Vöő Graduand Elena Valli Matricolation number 871686 Academic Year 2019/2020 Index 0. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. The Seven Deadly Sins: Anthony Hecht and the Emblematic Tradition ........................ 3 1.1. Emblematic Poetry .................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1. Hecht’s Emblematic View of Nature ............................................................ 3 1.1.2. Hecht’s Emblematic Practice........................................................................ 4 1.1.3. A Definition and History of Emblems .......................................................... 5 1.1.4. Metaphysical Poetry and the Emblematic Tradition ................................... 8 1.2. The Seven Deadly Sins ............................................................................................ 10 1.2.1. “Pride” ........................................................................................................ 13 1.2.2. “Envy” ........................................................................................................ 20 1.2.3. “Wrath” ...................................................................................................... -

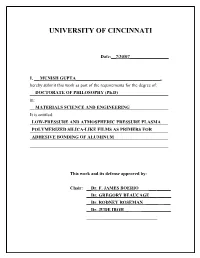

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__7/30/07_________________ I, __ MUNISH GUPTA_____________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) in: MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING It is entitled: LOW-PRESSURE AND ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE PLASMA POLYMERIZED SILICA-LIKE FILMS AS PRIMERS FOR ADHESIVE BONDING OF ALUMINUM This work and its defense approved by: Chair: __Dr. F. JAMES BOERIO ___ ______ __Dr. GREGORY BEAUCAGE __ ___ __ __Dr. RODNEY ROSEMAN _____ ___ __Dr. JUDE IROH _ _____________ _______________________________ LOW-PRESSURE AND ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE PLASMA POLYMERIZED SILICA-LIKE FILMS AS PRIMERS FOR ADHESIVE BONDING OF ALUMINUM A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) in the Department of Chemical and Material Engineering of the College of Engineering 2007 by Munish Gupta M.S., University of Cincinnati, 2005 B.E., Punjab Technical University, India, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. F. James Boerio i ABSTRACT Plasma processes, including plasma etching and plasma polymerization, were investigated for the pretreatment of aluminum prior to structural adhesive bonding. Since native oxides of aluminum are unstable in the presence of moisture at elevated temperature, surface engineering processes must usually be applied to aluminum prior to adhesive bonding to produce oxides that are stable. Plasma processes are attractive for surface engineering since they take place in the gas phase and do not produce effluents that are difficult to dispose off. Reactive species that are generated in plasmas have relatively short lifetimes and form inert products. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base.