S-0884-0023-09-00001.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 P.M

United N ation..'i FIRST COMMIITEE, 730tb GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 p.m. NINTH SESSION Official Records New York CONTENTS The motion was adopted by 25 votes to 2, with 3 Page abstentions. l.genda item 61: The meeting was suspended at 3.50 p.m. and resumed The question of \Vest Irian (West New Guinea) (con- at 4.20 p.m. tinued) . 417 Mr. Johnson (Canada), Vice-Chairman, took the Chair. Chairman: Mr. Francisco URRUTIA (Colombia). 8. Mr. MUNRO (New Zealand) described the rea "ons why his delegation had been unable to support the inscription of the item on the agenda. Previous United Nations consideration of the question had been AGENDA ITEM 61 in another organ and another context. Although a prima facie case for competence might exist, the new circumstances of the item required consideration of rhe question of West Irian (West New Guinea) the desirability of its inscription on practical as well (A/2694, A/C.l/L.l09) (continued) as legal grounds. After listening to the debate and considering the only draft resolution (AjC.1/L.109) Sayed ABOU-TALEB (Yemen) felt that there before the Committee, his delegation doubted whether .'as no doubt as to the competence of the United any useful purpose would be served by the considera htions to discuss the question of \Vest Irian. The tion of the item. vorld was fortunate to be able to bring such issues 9. New Zealand was intervening in the debate to efore the United Nations and thereby avert further place on record both its friendly feelings towards eterioration in international relations. -

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio. -

The Indonesian Struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949

The Indonesian struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949 Excessive violence examined University of Amsterdam Bastiaan van den Akker Student number: 11305061 MA Holocaust and Genocide Studies Date: 28-01-2021 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ugur Ümit Üngör Second Reader: Dr. Hinke Piersma Abstract The pursuit of a free Indonesian state was already present during Dutch rule. The Japanese occupation and subsequent years ensured that this pursuit could become a reality. This thesis examines the last 4 years of the Indonesian struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949. Excessive violence prevailed during these years, both the Indonesians and the Dutch refused to relinquish hegemony on the archipelago resulting in around 160,000 casualties. The Dutch tried to forget the war of Indonesian Independence in the following years. However, whistleblowers went public in the 1960’s, resulting in further examination into the excessive violence. Eventually, the Netherlands seems to have come to terms with its own past since the first formal apologies by a Dutch representative have been made in 2005. King Willem-Alexander made a formal apology on behalf of the Crown in 2020. However, high- school education is still lacking in educating students on these sensitive topics. This thesis also discusses the postwar years and the public debate on excessive violence committed by both sides. The goal of this thesis is to inform the public of the excessive violence committed by Dutch and Indonesian soldiers during the Indonesian struggle for Independence. 1 Index Introduction -

The Dutch Strategic and Operational Approach in the Indonesian War of Independence, 1945– 1949

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 46, Nr 2, 2018. doi: 10.5787/46-2-1237 THE DUTCH STRATEGIC AND OPERATIONAL APPROACH IN THE INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1945– 1949 Leopold Scholtz1 North-West University Abstract The Indonesian War of Independence (1945–1949) and the Dutch attempt to combat the insurgency campaign by the Indonesian nationalists provides an excellent case study of how not to conduct a counter-insurgency war. In this article, it is reasoned that the Dutch security strategic objective – a smokescreen of autonomy while keeping hold of political power – was unrealistic. Their military strategic approach was very deficient. They approached the war with a conventional war mind- set, thinking that if they could merely reoccupy the whole archipelago and take the nationalist leaders prisoner, that it would guarantee victory. They also mistreated the indigenous population badly, including several mass murders and other war crimes, and ensured that the population turned against them. There was little coordination between the civilian and military authorities. Two conventional mobile operations, while conducted professionally, actually enlarged the territory to be pacified and weakened the Dutch hold on the country. By early 1949, it was clear that the Dutch had lost the war, mainly because the Dutch made a series of crucial mistakes, such as not attempting to win the hearts and minds of the local population. In addition, the implacable opposition by the United States made their war effort futile. Keywords: Indonesian War of Independence, Netherlands, insurgency, counter- insurgency, police actions, strategy, operations, tactics, Dutch army Introduction Analyses of counter-insurgency operations mostly concentrate on the well- known conflicts – the French and Americans in Vietnam, the British in Malaya and Kenya, the French in Algeria, the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique, the Ian Smith government in Rhodesia, the South Africans in Namibia, et cetera. -

Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Decolonization and the Military: the Case of the Netherlands A Study in Political Reaction Rob Kroes, University of Amsterdam I Introduction *) When taken together, title and subtitle of this paper may seem to suggest, but certainly are not meant to implicate, that only m ilitary circles are apt to engage in right-wing political activism. On the contrary, this paper tries to indicate what specific groups within the armed forces of the Netherlands had an interest in opposing Indonesian independence, and what strategic alliances they engaged in with right- w in g c ivilian circles. In that sense, the subject of the paper is rather “underground” civil-military relations, as they exist alongside the level of institutionalized civil- m ilitary relations. Our analysis starts from a systematic theoretical perspective which, on the one hand, is intended to specify our expectations as to what interest groups within and without the m ilitary tended to align in opposing Indonesian independence and, on the other hand, to broadly characterize the options open to such coalitions for influencing the course of events either in the Netherlands or in the Dutch East Indies. II The theoretical perspective In two separate papers2) a process model of conflict and radicalism has been developed and further specified to serve as a basis for the study of m ilitary intervention in domestic politics. The model, although social-psychological in its emphasis on the *) I want to express my gratitude to the following persons who have been willing to respond to my request to discuss the role of the military during the Indonesian crisis: Messrs. -

Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia

Inquiry Australia's with Organisation: Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia Contact Person: Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia 8 Darwin Avenue YARRALUMLA ACT 2600 Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee — AUSTRALIA BILATERAL RELATIONS i. General 1. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1949, the overall Indonesia and Australia ties have been rock-solid and based on the principles of mutual respect, mutual understanding and mutual benefit. It is to be noted that with vast socio-political differences, the two neighboring countries have occasionally encountered a number of ups- and-downs in their relations. 2. The relations between Indonesia and Australia nose-dived when both countries confronted with internal as well as external pressures, which inter alia related to issues of human rights, good governance, democratization, self-determination, and terrorism. The roughest being the period after the popular consultations held in East Timor, which resulted in the separation of East Timor from Indonesia in 1999. Another issue that created formidable hurdles in Indonesia - Australia bilateral ties was the Afghani and Iraqi refugee's crisis, better known as the Tampa crisis. The leaders of the two neighboring countries had also differed on the US-led invasion of Afghanistan following the September 11 terrorist attacks. 3. The current relations between Indonesia and Australia have swung back to its springtime. A strong commitment to put bilateral relations on the right track was shown by the successful outcome of the 5th Meeting of the Australia - Indonesia Ministerial Forum (AIMF) in Canberra on 7 - 8 December 2000, attended by sixteen Australian and Indonesian ministers. -

Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions

NHBB B-Set Bee 2016-2017 Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions (1) As a state representative, this man sponsored the anti-contraception law that was overturned a century later in Griswold v. Connecticut. This man built two mansions in Bridgeport and patronized the U.S. tour of the \Swedish Nightingale," opera singer Jenny Lind. This business partner of James Bailey died three decades before his company was merged with that of the Ringling Brothers. For the point, name this 19th century entrepreneur whose \Greatest Show on Earth" became America's largest circus. ANSWER: Phineas Taylor \P.T." Barnum (2) Troops were parachuted into this battle during Operation Castor. The outposts Beatrice and Gabrielle were captured during this battle, in which Charles Piroth committed suicide by hand grenade after failing to destroy the camouflaged artillery of Vo Nguyen Giap. This battle led to the signing of the Geneva Accords, in which one side agreed to withdraw from Indochina. For the point, name this 1953 victory for the Viet Minh in their struggle for independence from France. ANSWER: Battle of Dien Bien Phu (3) Fighting in this war included the shelling of dockyards at Sveaborg. This conflict escalated when one side claimed the right to protect holy places in Palestine, and its immediate cause was the destruction of an Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Sinope [sin-oh-pee]. The Thin Red Line participated in the Battle of Balaclava, part of the effort to besiege Sevastopol during this war. The Light Brigade charged in, for the point, what 1850s war between Russia and a Franco-British alliance on a Black Sea peninsula? ANSWER: Crimean War (4) For his failure to warn the United States about this event, Michael Fortier was sentenced to twelve years in prison in 1998. -

“What Do They Know?”

“What do they know?” A qualitative comparative research into the narratives of Dutch history schoolbooks and of Dutch Indies-veterans on the decolonisation of Indonesia (1945-1949) Victimology and Criminal Justice Master’s thesis Iris Becx ANR: 975007 Supervisors: Prof. Dr. A. Pemberton and Dr. S. B. L. Leferink 13 January 2017 Voorwoord Met gepaste trots presenteer ik u mijn masterscriptie. In veel soortgelijke voorwoorden komen de woorden ‘bloed, zweet en tranen’ voor, maar die duiding zou ik niet willen gebruiken. Natuurlijk was het schrijfproces soms frustrerend, leek er geen eind aan te komen, of zag ik door de bomen het bos niet meer. Ik werd op de proef gesteld doordat er te weinig, of juist te veel literatuur was gepubliceerd, en toen eindelijk de puzzelstukjes van mijn theoretisch kader op hun plek waren gevallen, sloeg ik het bestand verkeerd op en verloor vervolgens alle weldoordachte formuleringen, waardoor ik weer van voor af aan kon beginnen. Toch is hier een ander spreekwoord meer op z’n plek, namelijk ‘zonder wrijving geen glans’, want uiteindelijk kijk ik toch vooral met plezier terug op het schrijven van deze thesis. Na al die maanden raak ik nog steeds onverminderd enthousiast van mijn onderzoek, en ben ik erachter gekomen dat ik onderzoek doen eigenlijk heel erg leuk vind. Omdat dit proces niet hetzelfde was verlopen zonder een aantal personen, wil ik graag van de mogelijkheid gebruik maken om ze hier te bedanken. De groep die ik de grootste dank verschuldigd ben, is de groep respondenten. Hartelijk bedankt voor uw tijd, het graven in uw geheugen, en het mij toevertrouwen van herinneringen. -

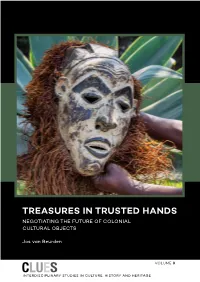

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Does Multicultural Indonesia Include Its Ethnic Chinese? 257

256 WacanaWacana Vol. 13Vol. No. 13 2 No. (October 2 (October 2011): 2011) 256—278 DEWI ANGGRAENI, Does multicultural Indonesia include its ethnic Chinese? 257 Does multicultural Indonesia include its ethnic Chinese? DEWI ANGGRAENI Abstract Multiculturalism in Indonesia is predominantly concerned with various regional cultures in the country, which continue to exist, and in some cases, to develop and progress. These cultures meet and interact in the context of a unitary national, Indonesian culture. There are however people who or whose ancestors originate from outside Indonesia, the major ones being Chinese and Arabs. They brought with them the cultures and mores of their lands of origin and to varying degrees integrated them into those of the places they adopted as homes. This article discusses how the Chinese who opted for Indonesian citizenship and nationality, fared and fare in Indonesia’s multicultural society, what problems slowed them in their path, and what lies behind these problems. Keywords Multicultural, cultural plurality, ethnic Chinese, peranakan, indigenous, migration, nationalism, VOC, New Order, Muslim, Confucianism, ancestry, Cheng Ho, pecinan, Chinese captaincy. What is multiculturalism? In Australia, the United States, and Canada, the media started to use the term multiculturalism from the late 1960s to the early 1970s to describe the nature of the society in their respective countries. It is worth noting that Australia, the United States and Canada have been immigrant-receiving nations where immigrants have had a very significant role in nation building and in economic growth. WorldQ.com explains the concept well and defines multiculturalism or DEWI ANGGRAENI is a writer of fiction and non-fiction.