Ageless Hero, Sexless Man: a Possible Pre- History and Three Hypotheses on Satyajit Ray's Feluda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Film & History: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies

Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies Volume 38, Issue 2, 2008, pp. 107-109 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_and_history/toc/flm.38.2.html Gaston Roberge, Satyajit Ray: Essays 1970-2005, Manohar, New Delhi (India), 2007, 280 pp., hb , ISBN: 81-7304-735-9 Reviewed by Gëzim Alpion In its scope and depth, Gaston Roberge’s new book on Satyajit Ray, is one of the most important publications to appear on this great twentieth-century film director since his 1992 death. The book includes twenty-four essays, which were written between 1970 and 2005. The timeline is important to trace the growth and maturity of Ray’s art as well as Roberge’s admiration for and appreciation of his oeuvre. The essays were originally prompted by teaching assignments and requests for articles as well as by Roberge’s long-standing and growing interest in the work and talent of the Calcutta-born filmmaker. Only Essay 8, the discussion of Jana Aranya (The Middle Man, 1975), was written for this collection to ‘complement’ the book and ‘improve’ Roberge’s ‘perception of the evolution’ (p. 14) he seeks to describe from the Apu trilogy to the Heart trilogy. Some of the essays have been edited slightly by the author to avoid repetition and, more importantly, to reflect important changes in technology since the time the articles were first published. So, for instance, in Essay 13, which appeared in print initially in 1974, Roberge rightly argues that the editing was warranted by the fact that, in the digital era, the technology of film can no longer be defined solely as the succession of still images. -

Premendra Mitra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Premendra Mitra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Premendra Mitra(1904 - 3 May 1988) Premendra Mitra was a renowned Bengali poet, novelist, short story writer and film director. He was also an author of Bangla science fiction and thrillers. <b>Life</b> He was born in Varanasi, India, though his ancestors lived at Rajpur, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His father was an employee of the Indian Railways and because of that; he had the opportunity of travelling to many places in India. He spent his childhood in Uttar Pradesh and his later life in Kolkata & Dhaka. He was a student of South Suburban School (Main) and later at the Scottish Church College in Kolkata. During his initial years, he (unsuccessfully) aspired to be a physician and studied the natural sciences. Later he started out as a school teacher. He even tried to make a career for himself as a businessman, but he was unsuccessful in that venture as well. At a time, he was working in the marketing division of a medicine producing company. After trying out the other occupations, in which he met marginal or moderate success, he rediscovered his talents for creativity in writing and eventually became a Bengali author and poet. Married to Beena Mitra, he was, by profession, a Bengali professor at City College in north Kolkata. He spent almost his entire life in a house at Kalighat, Kolkata. <b>As an Author & Editor</b> In November 1923, Mitra came from Dhaka, Bangladesh and stayed in a mess at Gobinda Ghoshal Lane, Kolkata. -

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

Annual Report 2012-2013 1 IIT Kanpur Publication and Outreach

Annual Report 2012-2013 Publication and Outreach Activities Books 1. ‘Instabilities of Flows and Transition to Turbulence’, Prof. T. K. Sengupta (CRC Press/ Taylor & Francis, USA, April 2012) 2. Tewari, A., Atmospheric and Space Flight Dynamics—Modeling and Simulation, Nov. 2012, National Defense Industry Press, Beijing, China (under contract with Springer (Birkhäuser), Boston, USA). 3. Triphenylbismuthane (Invited) Maddali L. N. Rao Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (John & Wiley, 2012) 4. Patra, N. R. (July 2012) “Ground Improvement Techniques” Vikash Publishing House Pvt Ltd, Noida, India, ISBN 978-93-259-6001-5 5. Raymahashay, B.C. and Sinha, R. (2012). Popular Book titled “Flood Disasters and Management: Indian Scenario” Bihar State Disaster Management Authority, Patna and Ministry of Earth Sciences, New Delhi, 44p. (both English and Hindi) 6. Sinha, R., Jain, V. and Tandon, S.K. (2012) River Systems and River Science in India: major drivers and challenges. In R. Sinha, R. Rasik (Eds) Earth Systems and Hazards, Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg, 244p. 7. Power system analysis, Prof. Saikat Chakrabarti 8. Synchrophasor applications in power systems, Prof. Saikat Chakrabarti 9. Philip Roth’s Heroic Ideal in Indignation and Nemesis. Critical Insights: Philip Roth. Ed. Aimee Pozorski. Massachusetts: Salem Press, 2013, 200-19, Prof. Gurumurthy Neelakantan 10. SaxenaK.K. (2012) "Output Growth during Post-liberalized India: An Input-Output Structural Decomposition Analysis" in Recession and Its Aftermath, ed by N M P Verma , Springer ( Co-author Rahul Arora and Srabjit Singh) 11. Mathur Somesh K with Luis Barreno, Maria Isabel and Rene Vasconez(2012), El Commercio De Bienes Amigables Con El Ambiente Y Otros Productos Especializados Del Ecuador(2012), UTE Press, UTE, Quito, Ecuador in Spanish 12. -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will and Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

AGANTUK – The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will And Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri It’s impossible to record the transition in the socio-political and cultural landscape of India in general and Bengal in particular without taking into account the contribution of Satyajit Ray. As author Peter Rainer says, ‘In Ray’s films the old and the new are inextricably joined. This is the great theme of all his movies: the way the past in India forever bleeds through the present.’ Today, Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has found a global market. But it may be useful to remember that if anyone can be credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map, it is Satyajit Ray. He pioneered a whole new sensibility about films and filmmaking that compelled the world to reshape its perception of Indian cinema. ‘What we need,’ he wrote in 1947, before he ever directed a film, ‘is a style, an idiom, a part of the iconography of cinema which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.’ This Still from the documentary, The Music of Satyajit Ray he achieved, and yet, like all great artists, his films went Watch film here- https://bit.ly/3u8orOD beyond the frontiers of countries and cultures. His contribution to the cultural scene in India is limited not just to his work as a director. He was the Renaissance man of independent India. As a film-maker he handled almost all the departments on his own – he wrote the screenplay and dialogues for his film, he composed his own music, designed the promotional material for his films, designed his own posters, went on to handle the cinematography and editing, was actively involved in the costumes (literally sketching each and every costume in a film). -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Satyajit Ray

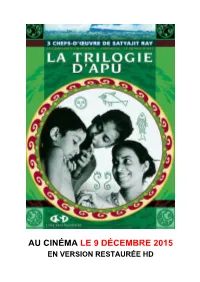

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana).