The Writing in Goopy Bagha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film & History: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies

Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies Volume 38, Issue 2, 2008, pp. 107-109 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_and_history/toc/flm.38.2.html Gaston Roberge, Satyajit Ray: Essays 1970-2005, Manohar, New Delhi (India), 2007, 280 pp., hb , ISBN: 81-7304-735-9 Reviewed by Gëzim Alpion In its scope and depth, Gaston Roberge’s new book on Satyajit Ray, is one of the most important publications to appear on this great twentieth-century film director since his 1992 death. The book includes twenty-four essays, which were written between 1970 and 2005. The timeline is important to trace the growth and maturity of Ray’s art as well as Roberge’s admiration for and appreciation of his oeuvre. The essays were originally prompted by teaching assignments and requests for articles as well as by Roberge’s long-standing and growing interest in the work and talent of the Calcutta-born filmmaker. Only Essay 8, the discussion of Jana Aranya (The Middle Man, 1975), was written for this collection to ‘complement’ the book and ‘improve’ Roberge’s ‘perception of the evolution’ (p. 14) he seeks to describe from the Apu trilogy to the Heart trilogy. Some of the essays have been edited slightly by the author to avoid repetition and, more importantly, to reflect important changes in technology since the time the articles were first published. So, for instance, in Essay 13, which appeared in print initially in 1974, Roberge rightly argues that the editing was warranted by the fact that, in the digital era, the technology of film can no longer be defined solely as the succession of still images. -

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

Flashback: Satyajit Ray's Professor Shonku and His Lost

TALKING FILMS Flashback: Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku and his lost project ‘The Alien’ All about the screenplay that reportedly inspired Steven Spielberg’s ‘E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial’. Chandrima Pal Mar 09, 2018 · 09:15 am Satyajit Ray’s alien Bengali director Sandip Ray’s latest movie features one of Satyajit Ray’s best-known literary creations. Not the detective Feluda, but Professor Shonku, the scientist and eccentric genius who was introduced by Sandip Ray’s father in 1961. Sandip Ray’s Professor Shonku O El Dorado is based on the story Nakur Babu O El Dorado, in which Shonku takes off on an adventure with a man who can see into the future and make people see things that are not immediately visible. Produced by leading Kolkata studio SVF, the movie will be shot in Bengal and Brazil, and is aiming for a release later this year. Shonku, to be played by thespian Dhritiman Chatterjee, has never been filmed before, unlike Feluda, about whom several movies and television serials have been made. Inspired partly by Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger and Hesoram Hushiar, a character created by Ray’s father Sukumar Ray, Shonku is every bit as fascinating as Feluda. He is a polyglot (he knows 69 languages), graduated from college at the age of 16, and started teaching when he was 20. Shonku works out of a laboratory at home where he uses locally available ingredients for his groundbreaking inventions. He keeps a low profile and refuses to share his formulas or inventions because he doesn’t want them to fall into the wrong hands. -

The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will and Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

AGANTUK – The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will And Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri It’s impossible to record the transition in the socio-political and cultural landscape of India in general and Bengal in particular without taking into account the contribution of Satyajit Ray. As author Peter Rainer says, ‘In Ray’s films the old and the new are inextricably joined. This is the great theme of all his movies: the way the past in India forever bleeds through the present.’ Today, Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has found a global market. But it may be useful to remember that if anyone can be credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map, it is Satyajit Ray. He pioneered a whole new sensibility about films and filmmaking that compelled the world to reshape its perception of Indian cinema. ‘What we need,’ he wrote in 1947, before he ever directed a film, ‘is a style, an idiom, a part of the iconography of cinema which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.’ This Still from the documentary, The Music of Satyajit Ray he achieved, and yet, like all great artists, his films went Watch film here- https://bit.ly/3u8orOD beyond the frontiers of countries and cultures. His contribution to the cultural scene in India is limited not just to his work as a director. He was the Renaissance man of independent India. As a film-maker he handled almost all the departments on his own – he wrote the screenplay and dialogues for his film, he composed his own music, designed the promotional material for his films, designed his own posters, went on to handle the cinematography and editing, was actively involved in the costumes (literally sketching each and every costume in a film). -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: a Study of Ray's Children's Fiction Hirak

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: A Study of Ray’s Children’s fiction Hirak Rajar Deshe Arpita Sarker Research Scholar (M.Phil.) University of Delhi India Abstract In my paper I intend to first explain different form of realism by discussing Ian Watt‟s definition of realism, in The Rise of The Novel comparing and contrasting it with Brecht and Luckas‟s idea of realism as explained in Bertolt Brecht: Against George Luckas. Secondly I will discuss in brief the difference between reality and realism in a work of fiction. Thirdly, I will talk about the portrayal of reality and realism in children‟s literature, using socialist realism and Brecht‟s view on it. In order to discuss third part of my paper I will analyze film maker Satyajit Ray and his socialist- realist- fantasy film Hirak Rajar Deshe. The movie is adapted from Ray‟s father‟s collection of work for children name Goopy Gayen and Bagha Bayen. Keywords: Fantasy, Reality, Realism, Socialism, Brecht. www.ijellh.com 50 Children‟s literature is a genre that is vastly dependent on fantastic elements that make it appealing to children and adults. The fantastic elements, on the surface, act as a model for psychologically cushioning that protects the child from the harsh realities of life and bestow moral messages to the masses. But the fantastical element alone cannot reveal the social, political, or moral message the fiction intends to spread. The fantasy element is hence paradoxical complicated by the presence of realism in Children‟s Literature. The use of realism, in the façade of fantasy, and larger than life characters, has helped writers to adhere to the real intention of children‟s literature. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Satyajit Ray

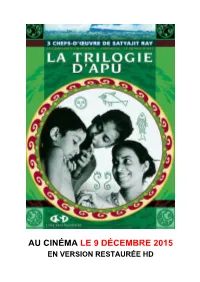

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

A Marxist Study of Ray's Film Hirak Rajar Deshe

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 “Dori Dhore Maro Taan / Raja Hobe Khan Khan”: A Marxist Study of Ray’s Film Hirak Rajar Deshe Dayal Chakrabortty* & Sambhunath Maji** *Independent Research Scholar, The University of Burdwan, W.B. **Assistant Professor, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, W.B. Received: May 30, 2018 Accepted: July 14, 2018 ABSTRACT From the very uncalendered past of society when system of production started its journey, automatically ‘class-struggle’ started to accompany it. Class-struggle is everywhere. In the age of slavery there was class struggle between slave-owners and slaves, in the age of Feudalism the class-struggle was between landowners and serfs and in capitalist society there is also class-struggle between Bourgeoisie and Proletariat. Lower class people or working class people or Proletariat people are always suppressed and oppressed by upper class people or the capitalists. This is the major aspect of Marxism. This Marxist approach is very much there in the Film Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray. Keywords: Class-Struggle, Capitalist Society, System of Production, Bourgeoisie and Proletariat, Marxism. “Marxist criticism has the longest history. Karl Marx himself made important general statements about culture and society in the 1850s. It is correct to think of Marxist criticism as a 20 th century phenomenon” (Selden, Widdowson, and Brooker 82). Marxism depends on temporal – spatial reality. The appropriation and application of it entirely depends on the consideration of time and place. Marxism is very much open to change. Karl Marx opines for a change for the betterment. -

The 59TH National Film Awards Function by : INVC Team Published on : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST

The 59TH National Film Awards function By : INVC Team Published On : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST [caption id="attachment_41188" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="The Dadasaheb Phalke Awardee, Shri Soumitra Chatterjee, film Producer, Shri Jaaved Jaaferi and Ashvin Kumar, the Producer, Director, Shri Sankalp Meshram, the film Director, Shri Satish Pande and the Director, Directorate of Film Festival, Shri Rajeev Kumar Jain at a Press Conference on the occasion of 59th National Film Awards Ceremony, organized by the DFF, in New Delhi."] [/caption] INVC,, Delhi,, The 59TH National Film Awards function will be held tomorrow at Vigyan Bhawan. The awards will be given away by the Hon’ble Vice President of India. Minister of Information & Broadcasting, Smt. Ambika Soni will also be present on the occasion. The highlights of the 59th National Film Awards are as follows: The top honour in the Feature Film category, the Best Film is shared by films Deool (Marathi) produced by Abhijeet Gholap & directed by Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni and Byari (Byari language) produced by T.H. Althaf Hussain & directed by Suveeram. The award carries Swarna Kamal and cash prize of Rs. 2,50,000/-. In Non- feature film category the top honour , Best Film goes to And We Play On (Hindi & English)directed and produced by Pramod Purswane . The awards carries Swarna Kamal and Cash prize of Rs. 1,50,000/-. In Best Writing on Cinema category the Swarna Kamal goes to the book titled R.D. Burman – The Man, The Music written by Anirudha Bhattacharjee & Balaji Vittal, published by Harper Collins India. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2.