POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

Artist Recreates Satyajit Ray S Film Posters on 100Th Birth Anniversary

Artist recreates Satyajit Ray's film posters on 100th birth anniversary to depict Covid crisis An artist marked 100 years of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray by recreating his iconic film posters to depict the Covid-19 crisis in India. Krishna Priya Pallavi Writer [email protected] If I am not writing on fashion, places you can travel to for that perfect holiday, mental health, trending topics, I am probably escaping the city for a vacation, eating a scrumptious meal at a quaint cafe, and so much more in between. Love to travel (obviously), dance, explore new places, read extensively and try out new and exciting dishes. Works as Senior Sub-Editor at India Today Digital. Aniket Mitra used posters from Satyajit Ray's iconic films to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India Photo: Facebook/Aniket Mitra Satyajit Ray had an inedible mark on the Indian cinema. His films are admired by cinephiles all over the world. May 2 marks 100 years since Satyajit Ray was born, and to celebrate his 100th birth anniversary, an artist paid the legendary filmmaker a poignant and relevant tribute. A Mumbai-based artist named Aniket Mitra celebrated the historic day by reimagining Satyajit Ray's iconic film posters amid the Covid times. ARTIST RECREATES SATYAJIT RAY'S FILM POSTERS TO DEPICT COVID CRISIS Aniket Mitra used ten films by Satyajit Ray to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India. Posters of films like Pather Panchali, Devi, Nayak, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya, Mahanagar, Ashani Sanket and more, were used to show the citizens' struggle during the second wave of the deadly virus. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: a Study of Ray's Children's Fiction Hirak

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: A Study of Ray’s Children’s fiction Hirak Rajar Deshe Arpita Sarker Research Scholar (M.Phil.) University of Delhi India Abstract In my paper I intend to first explain different form of realism by discussing Ian Watt‟s definition of realism, in The Rise of The Novel comparing and contrasting it with Brecht and Luckas‟s idea of realism as explained in Bertolt Brecht: Against George Luckas. Secondly I will discuss in brief the difference between reality and realism in a work of fiction. Thirdly, I will talk about the portrayal of reality and realism in children‟s literature, using socialist realism and Brecht‟s view on it. In order to discuss third part of my paper I will analyze film maker Satyajit Ray and his socialist- realist- fantasy film Hirak Rajar Deshe. The movie is adapted from Ray‟s father‟s collection of work for children name Goopy Gayen and Bagha Bayen. Keywords: Fantasy, Reality, Realism, Socialism, Brecht. www.ijellh.com 50 Children‟s literature is a genre that is vastly dependent on fantastic elements that make it appealing to children and adults. The fantastic elements, on the surface, act as a model for psychologically cushioning that protects the child from the harsh realities of life and bestow moral messages to the masses. But the fantastical element alone cannot reveal the social, political, or moral message the fiction intends to spread. The fantasy element is hence paradoxical complicated by the presence of realism in Children‟s Literature. The use of realism, in the façade of fantasy, and larger than life characters, has helped writers to adhere to the real intention of children‟s literature. -

Mahanagar Gas Limited Consistent Margin Outperformance; Earnings Outlook Improving

Mahanagar Gas Limited Consistent margin outperformance; earnings outlook improving Powered by the Sharekhan 3R Research Philosophy Oil & Gas Sharekhan code: MGL Result Update Update Stock 3R MATRIX + = - Summary Right Sector (RS) ü Q3FY2021 operating profit/PAT at Rs. 317 crore/Rs. 217 crore; up 22.4%/16.7% y-o-y and in-line with our estimates but were higher by 12%/10% versus consensus estimates led by Right Quality (RQ) ü a sharp recovery in gas sales volumes (up 32.2% q-o-q) and record-high EBITDA margins of Rs. 12.4/scm (up 34.8% y-o-y). Right Valuation (RV) ü CNG/Domestic PNG volume stood at 85%/124% of pre-COVID-19 level at 1.9 mmscmd/0.5 mmscmd; Industrial/Commercial (I/C) PNG volume declined by 9% y-o-y. Highest ever + Positive = Neutral - Negative gross margins of Rs. 17.7/scm (up 27.6% y-o-y). Improving volume and sustainable high margin bode well for a strong Q4FY21. Double- What has changed in 3R MATRIX digit volume growth guidance for FY22 and a 5-6% growth thereafter would drive an 18% PAT CAGR over FY21E-FY23E. Old New MGL’s underperformance to Sensex is likely to reverse as earnings outlook has improved and overhang of open access is over. Valuation of 12.1x its FY23E EPS is most attractive in RS the CGD space. We retain Buy on MGL with an unchanged PT of Rs. 1,380. RQ Mahanagar Gas Limited’s (MGL) Q3FY2021 operating profit of Rs. 317 crore (up 22.4% y-o-y; up 43.3% q-o-q) was in line with our estimates but 12% higher-than the consensus estimate RV of Rs. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

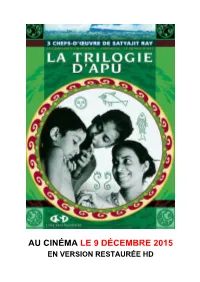

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray.