Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will and Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

AGANTUK – The Humanism of Satyajit Ray, His Last Will And Testament Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri It’s impossible to record the transition in the socio-political and cultural landscape of India in general and Bengal in particular without taking into account the contribution of Satyajit Ray. As author Peter Rainer says, ‘In Ray’s films the old and the new are inextricably joined. This is the great theme of all his movies: the way the past in India forever bleeds through the present.’ Today, Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has found a global market. But it may be useful to remember that if anyone can be credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map, it is Satyajit Ray. He pioneered a whole new sensibility about films and filmmaking that compelled the world to reshape its perception of Indian cinema. ‘What we need,’ he wrote in 1947, before he ever directed a film, ‘is a style, an idiom, a part of the iconography of cinema which would be uniquely and recognizably Indian.’ This Still from the documentary, The Music of Satyajit Ray he achieved, and yet, like all great artists, his films went Watch film here- https://bit.ly/3u8orOD beyond the frontiers of countries and cultures. His contribution to the cultural scene in India is limited not just to his work as a director. He was the Renaissance man of independent India. As a film-maker he handled almost all the departments on his own – he wrote the screenplay and dialogues for his film, he composed his own music, designed the promotional material for his films, designed his own posters, went on to handle the cinematography and editing, was actively involved in the costumes (literally sketching each and every costume in a film). -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Artist Recreates Satyajit Ray S Film Posters on 100Th Birth Anniversary

Artist recreates Satyajit Ray's film posters on 100th birth anniversary to depict Covid crisis An artist marked 100 years of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray by recreating his iconic film posters to depict the Covid-19 crisis in India. Krishna Priya Pallavi Writer [email protected] If I am not writing on fashion, places you can travel to for that perfect holiday, mental health, trending topics, I am probably escaping the city for a vacation, eating a scrumptious meal at a quaint cafe, and so much more in between. Love to travel (obviously), dance, explore new places, read extensively and try out new and exciting dishes. Works as Senior Sub-Editor at India Today Digital. Aniket Mitra used posters from Satyajit Ray's iconic films to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India Photo: Facebook/Aniket Mitra Satyajit Ray had an inedible mark on the Indian cinema. His films are admired by cinephiles all over the world. May 2 marks 100 years since Satyajit Ray was born, and to celebrate his 100th birth anniversary, an artist paid the legendary filmmaker a poignant and relevant tribute. A Mumbai-based artist named Aniket Mitra celebrated the historic day by reimagining Satyajit Ray's iconic film posters amid the Covid times. ARTIST RECREATES SATYAJIT RAY'S FILM POSTERS TO DEPICT COVID CRISIS Aniket Mitra used ten films by Satyajit Ray to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India. Posters of films like Pather Panchali, Devi, Nayak, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya, Mahanagar, Ashani Sanket and more, were used to show the citizens' struggle during the second wave of the deadly virus. -

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: a Study of Ray's Children's Fiction Hirak

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: A Study of Ray’s Children’s fiction Hirak Rajar Deshe Arpita Sarker Research Scholar (M.Phil.) University of Delhi India Abstract In my paper I intend to first explain different form of realism by discussing Ian Watt‟s definition of realism, in The Rise of The Novel comparing and contrasting it with Brecht and Luckas‟s idea of realism as explained in Bertolt Brecht: Against George Luckas. Secondly I will discuss in brief the difference between reality and realism in a work of fiction. Thirdly, I will talk about the portrayal of reality and realism in children‟s literature, using socialist realism and Brecht‟s view on it. In order to discuss third part of my paper I will analyze film maker Satyajit Ray and his socialist- realist- fantasy film Hirak Rajar Deshe. The movie is adapted from Ray‟s father‟s collection of work for children name Goopy Gayen and Bagha Bayen. Keywords: Fantasy, Reality, Realism, Socialism, Brecht. www.ijellh.com 50 Children‟s literature is a genre that is vastly dependent on fantastic elements that make it appealing to children and adults. The fantastic elements, on the surface, act as a model for psychologically cushioning that protects the child from the harsh realities of life and bestow moral messages to the masses. But the fantastical element alone cannot reveal the social, political, or moral message the fiction intends to spread. The fantasy element is hence paradoxical complicated by the presence of realism in Children‟s Literature. The use of realism, in the façade of fantasy, and larger than life characters, has helped writers to adhere to the real intention of children‟s literature. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

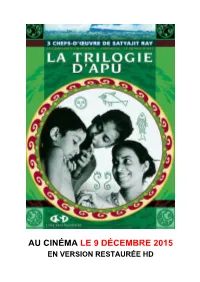

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

A Marxist Study of Ray's Film Hirak Rajar Deshe

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 “Dori Dhore Maro Taan / Raja Hobe Khan Khan”: A Marxist Study of Ray’s Film Hirak Rajar Deshe Dayal Chakrabortty* & Sambhunath Maji** *Independent Research Scholar, The University of Burdwan, W.B. **Assistant Professor, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, W.B. Received: May 30, 2018 Accepted: July 14, 2018 ABSTRACT From the very uncalendered past of society when system of production started its journey, automatically ‘class-struggle’ started to accompany it. Class-struggle is everywhere. In the age of slavery there was class struggle between slave-owners and slaves, in the age of Feudalism the class-struggle was between landowners and serfs and in capitalist society there is also class-struggle between Bourgeoisie and Proletariat. Lower class people or working class people or Proletariat people are always suppressed and oppressed by upper class people or the capitalists. This is the major aspect of Marxism. This Marxist approach is very much there in the Film Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray. Keywords: Class-Struggle, Capitalist Society, System of Production, Bourgeoisie and Proletariat, Marxism. “Marxist criticism has the longest history. Karl Marx himself made important general statements about culture and society in the 1850s. It is correct to think of Marxist criticism as a 20 th century phenomenon” (Selden, Widdowson, and Brooker 82). Marxism depends on temporal – spatial reality. The appropriation and application of it entirely depends on the consideration of time and place. Marxism is very much open to change. Karl Marx opines for a change for the betterment. -

APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 Min

3 October 2006 XIII:5 APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 min. Produced, written and directed by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay Original Music by Ravi Shankar Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Kanu Bannerjee ... Harihar Ray Karuna Bannerjee ... Sarbojaya Ray Pinaki Sengupta ... Apu (young) Smaran Ghosal ... Apu (adolescent) Santi Gupta ... Ginnima Ramani Sengupta ... Bhabataran Ranibala ... Teliginni Sudipta Roy ... Nirupama Ajay Mitra ... Anil Charuprakash Ghosh ... Nanda Subodh Ganguli ... Headmaster Mani Srimani ... Inspector Hemanta Chatterjee ... Professor Kali Bannerjee ... Kathak Kalicharan Roy ... Akhil, press owner Kamala Adhikari ... Mokshada Lalchand Banerjee ... Lahiri K.S. Pandey ... Pandey Meenakshi Devi ... Pandey's wife Anil Mukherjee ... Abinash Harendrakumar Chakravarti ... Doctor Bhaganu Palwan ... Palwan SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India—23 April 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films. He is best known in the west for the Apu Trilogy— Apur Sansar/The World of Apu (1959), Aparajito/The Unvanquished (1957), and (his first film) Pather Panchali/Song of the Road (1955) and for Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958). His last films were Agantuk (1991), Shakha Proshakha (1990), Ganashatru/An Enemy of the People (1989), Sukumar Ray (1987), Ghare-Baire/The Home and the World (1984) and Heerak Rajar Deshe/The Kingdom of Diamonds (1980). He was given an honorary Academy Award in 1992. SUBRATA MITRA (12 October 1930, Calcutta, West Bengal, India—7 December 2001) shot 17 films, 10 of them for Ray, including all three Apu films, Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958) and Parash Pathar/The Philosopher’s Stone (1958). His last film was New Delhi Times (1986). -

The 59TH National Film Awards Function by : INVC Team Published on : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST

The 59TH National Film Awards function By : INVC Team Published On : 2 May, 2012 09:45 PM IST [caption id="attachment_41188" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="The Dadasaheb Phalke Awardee, Shri Soumitra Chatterjee, film Producer, Shri Jaaved Jaaferi and Ashvin Kumar, the Producer, Director, Shri Sankalp Meshram, the film Director, Shri Satish Pande and the Director, Directorate of Film Festival, Shri Rajeev Kumar Jain at a Press Conference on the occasion of 59th National Film Awards Ceremony, organized by the DFF, in New Delhi."] [/caption] INVC,, Delhi,, The 59TH National Film Awards function will be held tomorrow at Vigyan Bhawan. The awards will be given away by the Hon’ble Vice President of India. Minister of Information & Broadcasting, Smt. Ambika Soni will also be present on the occasion. The highlights of the 59th National Film Awards are as follows: The top honour in the Feature Film category, the Best Film is shared by films Deool (Marathi) produced by Abhijeet Gholap & directed by Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni and Byari (Byari language) produced by T.H. Althaf Hussain & directed by Suveeram. The award carries Swarna Kamal and cash prize of Rs. 2,50,000/-. In Non- feature film category the top honour , Best Film goes to And We Play On (Hindi & English)directed and produced by Pramod Purswane . The awards carries Swarna Kamal and Cash prize of Rs. 1,50,000/-. In Best Writing on Cinema category the Swarna Kamal goes to the book titled R.D. Burman – The Man, The Music written by Anirudha Bhattacharjee & Balaji Vittal, published by Harper Collins India.