Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

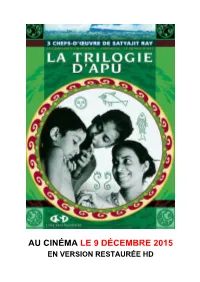

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

A Marxist Study of Ray's Film Hirak Rajar Deshe

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 “Dori Dhore Maro Taan / Raja Hobe Khan Khan”: A Marxist Study of Ray’s Film Hirak Rajar Deshe Dayal Chakrabortty* & Sambhunath Maji** *Independent Research Scholar, The University of Burdwan, W.B. **Assistant Professor, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, W.B. Received: May 30, 2018 Accepted: July 14, 2018 ABSTRACT From the very uncalendered past of society when system of production started its journey, automatically ‘class-struggle’ started to accompany it. Class-struggle is everywhere. In the age of slavery there was class struggle between slave-owners and slaves, in the age of Feudalism the class-struggle was between landowners and serfs and in capitalist society there is also class-struggle between Bourgeoisie and Proletariat. Lower class people or working class people or Proletariat people are always suppressed and oppressed by upper class people or the capitalists. This is the major aspect of Marxism. This Marxist approach is very much there in the Film Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray. Keywords: Class-Struggle, Capitalist Society, System of Production, Bourgeoisie and Proletariat, Marxism. “Marxist criticism has the longest history. Karl Marx himself made important general statements about culture and society in the 1850s. It is correct to think of Marxist criticism as a 20 th century phenomenon” (Selden, Widdowson, and Brooker 82). Marxism depends on temporal – spatial reality. The appropriation and application of it entirely depends on the consideration of time and place. Marxism is very much open to change. Karl Marx opines for a change for the betterment. -

Animating Folktales: an Analysis of Animation Movies Based On

Litinfinite Journal, Vol-2, Issue-2, (2nd December, 2020) ISSN: 2582-0400 [Online], CODEN: LITIBR DOI: 10.47365/litinfinite.2.2.2020.64-75 Page No: 64-75, Section: Article Animating Folktales: An Analysis of Animation Movies based on Folktales of three different Indian Languages Maya Bhowmick1 1Student, Department of Communication and Journalism, Gauhati University, Guwahati, India. Mail Id: [email protected] Ankuran Dutta2 2Associate Professor and Head, Department of Communication and Journalism, Gauhati University, Guwahati, India. Mail Id: [email protected] | Orchid ID: 0000-0002-0637-9846 Abstract Folktales are the oldest and traditional means of communication having remained a powerful means of communication over the years. Since its inception this method of storytelling and communicating has changed its medium of transmission but not its manner of storytelling. For ages, oral tradition has been a medium of transmission of these stories and culture but with modernization, the medium changed to print, electronic, and now digital media. These folktales do not represent mere stories; but communicate the varied culture, tradition, rituals, history and much other vital information reflecting the timeline of various communities. Serving as an active agent of both information and entertainment at the community level for so many years today, there arises an immediate need to preserve this form of storytelling - Folktales, especially in the context of its presentation has witnessed a change in recent times. Animation being the latest medium of entertainment, folktales can also be narrated in the form of animation that will also help preserve the stories in animated form for future generations. -

Folklore and Folkloristics; Vol. 4, No. 2. (December 2011) Bengali Graphic

Folklore and Folkloristics; Vol. 4, No. 2. (December 2011) Article-4 Bengali graphic novels for children-Sustaining an intangible heritage of storytelling traditions from oral to contemporary literature - Dr. Lopamudra Maitra Abstract The paper looks into graphic novels acting as an important part of preserving and sustaining a part of intangible heritage and a specific trend of socio-cultural traditions pertaining to children across the globe- the art of storytelling. In West Bengal, the art of storytelling for children sustains itself through time through various proverbs, anecdotes, rhymes and stories, handed down from generations and expressing more than mere words in oral tradition. Occupying a significant aspect of communication even in recent times, the publication and recent popularity of several graphic novels in Bengali have reintroduced several of these stories from oral tradition yet again with the help of popular culture. Along with the plethora of such stories from oral tradition is the recent range of literature for children in Bengali. Thus, the variety of graphic novels include various stories which were collected and published from oral traditions nearly a hundred years back, to the most recent creations of printed literature for children. The conceptions embrace the efforts of stalwarts of Bengali children’s literature, including, Dakkhinaranjan Mitra Majumdar, Upendrakishore Raychowdhury, Sukumar Ray, Satyajit Ray, Shibram Chakraborty, Narayan Gangopadhyay, Premendra Mitra and others. Exploring a significant part of the intangible heritage of mankind- the art of storytelling for children survives across the globe in varied and myriad hues of expression- with two significant contributors occupying centre stage- the narrator and the listener. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Please Turn Off Cellphones During Screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, the MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 Min.)

Please turn off cellphones during screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, THE MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 min.) Directed, produced and written by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Tarashankar Banerjee Original Music by Ustad Vilayat Khan, Asis Kumar , Robin Majumder and Dakhin Mohan Takhur Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Chhabi Biswas…Huzur Biswambhar Roy Padmadevi…Mahamaya, Roy's wife Pinaki Sengupta…Khoka, Roy's Son Gangapada Basu…Mahim Ganguly Tulsi Lahiri…Manager of Roy's Estate Kali Sarkar…Roy's Servant Waheed Khan…Ujir Khan Roshan Kumari…Krishna Bai, dancer SATYAJIT RAY (May 2, 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India – April 23, 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films: 1991 The Visitor, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Elephant God (novel / screenplay), 1977 The Chess Players, Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray, 1984 The Home and 1976 The Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company the World, 1984 “Deliverance”, 1981 “Pikoor Diary”, 1980 The Limited, 1973 Distant Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The Elephant Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, 1970 Days and Nights in the Forest, God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 The Middleman, 1976 Bala, 1970 Baksa Badal, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company Limited, 1973 Distant 1967 The Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 Kapurush: The Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, Coward, 1965 Mahapurush: The Holy Man, 1964 The Big City: 1970 Days -

Oral Traditions, Folklore and Archaeology

Volume II Issue I, April 2014 ISSN 2321 - 7065 Complimentary disciplines and their significance in India- Oral traditions, folklore and archaeology. By Dr. Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai MA, MDMC, PhD Assistant Professor and Visual Anthropologist - Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication (SIMC) - UG, Pune- under Symbiosis International University Abstract- The paper is an attempt towards understanding the importance of the disciplines of folklore and culture studies, especially those pertaining to the oral tradition which forms an important part of the intangible heritage of man and his environment and the discipline of archaeology in India. Both are complimentary disciplines and needs to be studied for a holistic understanding of the term culture and folk traditions in a society. The paper traces a brief background of both the disciplines of folklore studies as well as archaeology as it developed in the sub-continent and thereby attempts to highlight the need to perceive and understand both. A cumulative study is an imperative necessity in the recent global world where the term ‘culture’ denotes a much wider definition than was connoted decades ago as part of the civilisation of man. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Key words- folklore studies, archaeology, tradition, supplementary studies -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------- 125 Volume II Issue I, April 2014 ISSN 2321 - 7065 Main paper- “If you take myth and folklore, and these things that speak in symbols, they can be interpreted in so many ways that although the actual image is clear enough, the interpretation is infinitely blurred, a sort of enormous rainbow of every possible colour you could imagine”- Diana Wynne Jones- British author (16 August 1934 – 26 March 2011- famous for her writings on fantasy novels for children and adults). -

Satyajit Ray Retrospective Opens Film India

Ill The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 39 *o For Immediate Release 5/26/81 COMPLETE SATYAJIT RAY RETROSPECTIVE OPENS FILM INDIA Artist, author, musician, and master filmmaker SATYAJIT RAY will introduce FILM INDIA, the largest and most comprehensive program of Indian cinema ever exhibited in this country. Presented by The Department of Film in conjunction with The Asia Society and the Indo-US Subcommission on Education and Culture, FILM INDIA is designed to broaden American awareness of the long history of Indian cinema as well as of the recent developments in Indian filmmaking. FILM INDIA is structured in three parts. The first section will comprise a retrospective of films (with English subtitles) of the internationally acclaimed director Satyajit Ray, including shorts and features that have not been previously exhibited in this country. Many new 35mm prints of Ray's films are being made specifically for this program, including his most recent feature, THE KINGDOM OF DIAMONDS (1980) and an even later work, PIKOO (1980), a short film. The complete Ray retrospective totals 29 films, June 25 - July 24. Satyajit Ray (Calcutta, 1921) was born into a distinguished Bengali family. After working for some years as an art director in an advertising firm, he completed — against tremendous odds — his first film, PATHER PANCHALI, in 1955. Its premiere at The Museum of Modern Art in May 1955, its acclaim at the 1956 Cannes Film Fest ival, and its immediate success throughout Bengal, encouraged Ray and enabled him to become a professional filmmaker. PATHER PANCHALI was followed by two sequels, forming the now famous APU Trilogy.