Conditions of Visibility : People's Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

The Writing in Goopy Bagha

International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Right(ing) the Writing: An Exploration of Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne Amrita Basu Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, West Bengal, India Abstract The act of writing, owing to the permanence it craves, may be said to be in continuous interaction with the temporal flow of time. It continues to stimulate questions and open up avenues for discussion. Writing people, events and relationships into existence is a way of negotiating with the illusory. But writing falters. This paper attempts a reading of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in terms of power politics through the lens of the manipulation of written codes and inscriptions in the film. Identities and cultures are constructed through inscriptions and writings. But in the wrong hands, this medium of communication which has the potential to bring people together may wreck havoc on the social and political system. Writing, or the misuse of it, in the case of the film, reveals the nature of reality as provisional. If writing gives a seal of authenticity to a message, it can also become the casualty of its own creation. Key words: Inscription, Power, Politics, Writing, Social system 1 International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) ISSN 2356-5926 Vol.1, Issue.2, September, 2014 Introduction Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne by Satyajit Ray is a fun film for children of all ages; it ran to packed houses in West Bengal for a record 51 weeks and is considered one of the most commercially successful Ray films. -

Tagore's Song Offerings: a Study on Beauty and Eternity

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Tagore’s Song Offerings: A Study on Beauty and Eternity Dr. Tinni Dutta Lecturer, Department of Psychology , Asutosh College Kolkata , India. ABSTRACT Gitanjali written by Rabindranath Tagore (and the English translation of the Corresponding Author: Bengali poems in it, written in 1921) was awarded the Novel Prize in 1913. He Dr. Tinni Dutta called it Song Offerings. Some of the songs were taken from „Naivedya‟, „Kheya‟, „Gitimalya‟ and other selections of his poem. That is, the Supreme Being is complete only together with the soul of the devetee. He makes the mere mortal infinite and chooses to do so for His own sake, this could be just could be a faint echo of the AdvaitaPhilosophy.Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali express the distinctive method of philosophy…The poet is nothing more than a flute (merely a reed) which plays His timeless melodies . His heart overflows with happiness at His touch that is intangible Tagore‟s song in Gitanjali are analyzed in this ways - content analysis and dynamic analysis. Methodology of his present study were corroborated with earlier findings: Halder (1918), Basu (1988), Sanyal (1992) Dutta (2002).In conclusion it could be stated that Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali are intermingled with beauty and eternity.A frequently used theme in Tagore‟s poetry, is repeated in the song,„Tumiaamaydekechhilechhutir‟„When the day of fulfillment came I knew nothing for I was absent –minded‟, He mourns the loss. This strain of thinking is found also in an exquisite poem written in old age. -

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora

Remembering Ray | Kanika Aurora Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem in the autograph book of young Satyajit whom he met in idyllic Shantiniketan. The poem, translated in English, reads: ‘Too long I’ve wandered from place to place/Seen mountains and seas at vast expense/Why haven’t I stepped two yards from my house/Opened my eyes and gazed very close/At a glistening drop of dew on a piece of paddy grain?’ Years later, Satyajit Ray the celebrated Renaissance Man, captured this beauty, which is just two steps away from our homes but which we fail to appreciate on our own in many of his masterpieces stunning the audience with his gritty, neo realistic films in which he wore several hats- writing all his screenplays with finely detailed sketches of shot sequences and experimenting in lighting, music, editing and incorporating unusual camera angles. Several of his films were based on his own stories and his appreciation of classical music is fairly apparent in his music compositions resulting in some rather distinctive signature Ray tunes collaborating with renowned classical musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar and Vilayat Khan. No surprises there. Born a hundred years ago in 1921 in an extraordinarily talented Bengali Brahmo family, Satyajit Ray carried forward his illustrious legacy with astonishing ease and finesse. Both his grandfather Upendra Kishore RayChaudhuri and his father Sukumar RayChaudhuri are extremely well known children’s writers. It is said that there is hardly any Bengali child who has not grown up listening to or reading Upendra Kishore’s stories about the feisty little bird Tuntuni or the musicians Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne. -

Postcolonial Resistance of India's Cultural Nationalism in Select Films

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 25 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies ISSN: 2456-7507 <postscriptum.co.in> Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed Volume V Number i (January 2020) Postcolonial Resistance of India’s Cultural Nationalism in Select Films of Rituparno Ghosh Koushik Mondal Research Scholar, Department of English, Visva Bharati Koushik Mondal is presently working as a Ph. D. Scholar on the Films of Rituparno Ghosh. His area of interest includes Gender and Queer Studies, Nationalism, Postcolonialism, Postmodernism and Film Studies. He has already published some articles in prestigious national and international journals. Abstract The paper would focus on the cultural nationalism that the Indians gave birth to in response to the British colonialism and Ghosh’s critique of such a parochial nationalism. The paper seeks to expose the irony of India’s cultural nationalism which is based on the phallogocentric principle informed by the Western Enlightenment logic. It will be shown how the idea of a modern India was in fact guided by the heteronormative logic of the British masters. India’s postcolonial politics was necessarily patriarchal and hence its nationalist agenda was deeply gendered. Exposing the marginalised status of the gendered and sexual subalterns in India’s grand narrative of nationalism, Ghosh questions the compatible comradeship of the “imagined communities”. Keywords Hinduism, postcolonial, nationalism, hypermasculinity, heteronormative postscriptum.co.in Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed ISSN 24567507 5.i January 20 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 26 India‟s cultural nationalism was a response to British colonialism. The celebration of masculine virility in India‟s cultural nationalism roots back to the colonial encounter. -

Satyajit's Bhooter Raja

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed ISSN: 2456-7507 postscriptum.co.in Volume II Number i (January 2017) Nag, Sourav K. “Decolonising the Eerie: ...” pp. 41-50 Decolonising the Eerie: Satyajit’s Bhooter Raja (the King of Ghosts) in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Sourav Kumar Nag Assistant Professor in English, Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya, Bankura The author is an assistant professor of English at Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya. He has published research articles in various national and international journals. His preferred literary areas include African literature, Literary Theory and Indian English Literature. At present, he is working on his PhD on Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Abstract This paper is a critical investigation of the socio-political situation of the Indianised spectral king (Bhooter Raja) in Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and also of Ray’s handling of the marginalised in the movie. The movie is read as an allegory of postcolonial struggle told from a regional perspective. Ray’s portrayal of the Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) is typically Indianised. He deliberately deviates from the colonial tradition of Gothic fiction and customised Upendrakishore’s tale as a postcolonial narrative. This paper focuses on Ray’s vision of regional postcolonialism. Keywords ghost, eerie, postcolonial, decolonisation, subaltern Nag, S. K. Decolonising the Eerie ... 42 I cannot help being nostalgic sitting on my desk to write on Satyajit Ray‟s adaptation of Goopy Gayne Bagha Bayne (1969). I remember how I gaped to watch the movie the first time on Doordarsan. Not being acquainted with Bhooter Raja (The king of ghosts) before, I got startled to see the shiny black shadow with flashing electric bulbs around and hearing his reverberated nasal chant of three blessings. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: a Study of Ray's Children's Fiction Hirak

Reality, Realism and Fantasy: A Study of Ray’s Children’s fiction Hirak Rajar Deshe Arpita Sarker Research Scholar (M.Phil.) University of Delhi India Abstract In my paper I intend to first explain different form of realism by discussing Ian Watt‟s definition of realism, in The Rise of The Novel comparing and contrasting it with Brecht and Luckas‟s idea of realism as explained in Bertolt Brecht: Against George Luckas. Secondly I will discuss in brief the difference between reality and realism in a work of fiction. Thirdly, I will talk about the portrayal of reality and realism in children‟s literature, using socialist realism and Brecht‟s view on it. In order to discuss third part of my paper I will analyze film maker Satyajit Ray and his socialist- realist- fantasy film Hirak Rajar Deshe. The movie is adapted from Ray‟s father‟s collection of work for children name Goopy Gayen and Bagha Bayen. Keywords: Fantasy, Reality, Realism, Socialism, Brecht. www.ijellh.com 50 Children‟s literature is a genre that is vastly dependent on fantastic elements that make it appealing to children and adults. The fantastic elements, on the surface, act as a model for psychologically cushioning that protects the child from the harsh realities of life and bestow moral messages to the masses. But the fantastical element alone cannot reveal the social, political, or moral message the fiction intends to spread. The fantasy element is hence paradoxical complicated by the presence of realism in Children‟s Literature. The use of realism, in the façade of fantasy, and larger than life characters, has helped writers to adhere to the real intention of children‟s literature. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Satyajit Ray

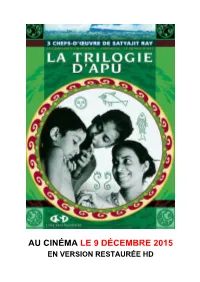

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 Min

3 October 2006 XIII:5 APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 min. Produced, written and directed by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay Original Music by Ravi Shankar Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Kanu Bannerjee ... Harihar Ray Karuna Bannerjee ... Sarbojaya Ray Pinaki Sengupta ... Apu (young) Smaran Ghosal ... Apu (adolescent) Santi Gupta ... Ginnima Ramani Sengupta ... Bhabataran Ranibala ... Teliginni Sudipta Roy ... Nirupama Ajay Mitra ... Anil Charuprakash Ghosh ... Nanda Subodh Ganguli ... Headmaster Mani Srimani ... Inspector Hemanta Chatterjee ... Professor Kali Bannerjee ... Kathak Kalicharan Roy ... Akhil, press owner Kamala Adhikari ... Mokshada Lalchand Banerjee ... Lahiri K.S. Pandey ... Pandey Meenakshi Devi ... Pandey's wife Anil Mukherjee ... Abinash Harendrakumar Chakravarti ... Doctor Bhaganu Palwan ... Palwan SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India—23 April 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films. He is best known in the west for the Apu Trilogy— Apur Sansar/The World of Apu (1959), Aparajito/The Unvanquished (1957), and (his first film) Pather Panchali/Song of the Road (1955) and for Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958). His last films were Agantuk (1991), Shakha Proshakha (1990), Ganashatru/An Enemy of the People (1989), Sukumar Ray (1987), Ghare-Baire/The Home and the World (1984) and Heerak Rajar Deshe/The Kingdom of Diamonds (1980). He was given an honorary Academy Award in 1992. SUBRATA MITRA (12 October 1930, Calcutta, West Bengal, India—7 December 2001) shot 17 films, 10 of them for Ray, including all three Apu films, Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958) and Parash Pathar/The Philosopher’s Stone (1958). His last film was New Delhi Times (1986). -

Satyajit Ray's Documentary Film “Rabindranath”

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH, VOL. I, ISSUE 6/ SEPEMBER 2013 ISSN 2286-4822, www.euacademic.org IMPACT FACTOR: 0.485 (GIF) Satyajit Ray’s Documentary Film “Rabindranath” : A Saga of Creative Excellence RATAN BHATTACHARJEE India Satyajit‟s Ray’s documentary film „Rabindranath‟ was a saga of creative excellence. Its wide range of conception is simply amazing. It is something more profound than a mere documentary. Ray was conscious that he was making an official portrait of India's celebrated poet and hence the film does not include any controversial aspects of Tagore's life. However, it is far from being a propaganda film. In his poem Matthew Arnold once paid his tribute to Shakespeare in the ever inimitable words: “Others abide our question. Thou art free. /We ask and ask: Thou smilest and art still,/Out-topping knowledge.” This is equally true of Satyajit Ray‟s Tagore. We ask and go on asking and Tagore smiles and is „stillout-topping knowledge‟. In 1623 the great Shakespearean editors did their fantastic job of publishing in the Folio edition posthumously the 36 out of the 37 plays. Almost comparable to this outstanding editing venture is the task undertaken by Satyajit Ray FASC (Film and Study Center) to develop its most comprehensive archive on the worksof Satyajit Ray. The total number of Ray films like Shakespeare‟s dramas is 37. „Rabindranath‟, the 54 min B/W documentary film directed by Satyajit Ray was a saga of creative excellence for its wide range of conception .Tagore is revered by the world‟s 250 million Bengali speakers in India and neighbouring 901 Ratan Bhattacharjee – Satyajit Ray’s Documentary Film “Rabindranath”: A Saga of Creative Excellence Bangladesh.