Offprint From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.Murtomäki 2017.10192 Words

Sibelius in the Context of the Finnish-German History Veijo Murtomäki Introduction The life and career of a composer cannot be considered as an isolated case without taking into account the wider context. The history of ideas and ideologies is always part of any serious enquiry into an artist’s personal history. Therefore we must bear in mind at least four points when considering the actions of artist and his or her country. Firstly, as the eminent Finnish historian Matti Klinge has observed, "the biggest challenge for understanding history is trying to situate oneself in the preconditions of the time-period under scrutiny while remembering that it did not know what the posterity knows."[1] Writing history is not primarily a task whereby the historian provides lines for actors to speak, but rather is an attempt to understand and explain why something happened, and to construct a context including all of the possible factors involved in a certain historical process. Secondly, supporting (or not opposing) an ideology prevailing at a certain time does not mean that the supporter (or non-opponent) is committing a crime. We could easily condemn half of the European intellectuals for supporting Fascism, Nazism, Communism or Maoism, or just for having become too easily attracted by these – in their mind – fascinating, visionary ideologies to shape European or world history. Thirdly, history has always been written by the winners – and thus, historiography tends to be distorted by exaggerating the evil of the enemy and the goodness of the victor. A moral verdict must be reached when we are dealing with absolute evil, but it is rare to find exclusively good or bad persons or civilizations; therefore history is rarely an issue of black and white. -

Krigen Mot Ryssarna I Vin Också En Utmarkelse Av Den Fin Det Er Imidlertid Tre Artikler Om Program.» Kultur

Stiftelsen norsk Okkupasjonshistorie, 2014 UAVHENGIG AVIS Nr.6 - 1992 - 41. årgang Finsk godgjøreIse KULTUR ER BASISVARE, til utenlandske IKHESTORMARKEDPRODUKT Jeg har skummet dagens A v Frederik Skaubo med overskrift: Rambo eller krigsdeltagere Morgenblad og bl.a. merket Rimbaud? hvor han angriper Efter 50 år får de svenska sol ersattning på knappt 1.500 kro meg datoen, 8. mai, som jo så selv om avskaffelse av familien det syn at staten (myndighe dater som frivilligt hjiilpte Fin nor får alla frivillige utlanningar absolutt gir grunn til ettertanke. var oppført på kommunistenes tene) også har noe ansvar for land i krigen mot ryssarna i vin också en utmarkelse av den fin Det er imidlertid tre artikler om program.» kultur. Han er såvisst ikke opp ter och fortsattningskriget 1939- ska staten. Ersattningen ar mera et annet viktig emne, jeg her fes Et fenomen idag er f.eks. at tatt av kultur som identitets 45 ekonomisk ersattning. en symbolisk gest av Finland tet meg ved. Hver for seg avkla mens Høyre med pondus pro fremmende, tradisjonsbevaren Det var i samband med det som i år firar sitt 75-års jubi rende, tildels avslørende i for klamerer en politikk bygget på de, kvalitetsskapende og estetisk årliga firandet av veterandagen i leum. bindelse med vårt kultursyn. De «det kristne verdigrunnlag ... og etisk oppdragende. Nesten Finland som regeringen fattade Framfor allt fOr de ester som er dessuten aktuelle også når vil forholdet for de flestes ved mer anarkistisk enn liberal går beslut om att hedra de 5.000 frivilligt deltog i striderna på denne avis kommer ut. -

Nasjonal Samlings Ideologiske Utvikling 1933- 1937

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives “Ja takk, begge deler” - en analyse av Nasjonal Samlings ideologiske utvikling 1933- 1937 Robin Sande Masteroppgave Institutt for statsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 12. desember 2008 1 Forord Arbeidet med denne oppgaven tok til i mars 2008. Ideen fikk jeg imidlertid under et utvekslingsopphold i Berlin vinteren 2007/08. Fagene ”Politische Theorie und Geschichte am Beispiel der Weimarer Republik” og ”Politische Philosophien im Kontext des Nationalsozialismus” gjorde meg oppmerksom på at Nasjonal Samling må ha vært noe mer enn bare vertskap for tyske invasjonsstyrker. Hans Fredrik Dahls eminente biografi om Quisling: En fører blir til, vekket interessen ytterligere. Oppgaven kunne selvfølgelig vært mye mer omfattende. Det foreligger uendelige mengder litteratur både om liberalistisk elitisme og spesielt fascisme. Nasjonal Samlings historie kunne også vært behandlet mye mer inngående dersom jeg hadde hatt tid til et mer omfattende kildesøk. Dette gjelder også persongalleriet i Nasjonal Samling som absolutt hadde fortjent både mer tid og plass. Fremtredende personer som Johan B.Hjorth, Halldis Neegård Østbye, Gulbrand Lunde og Hans S.Jacobsen kunne hver for seg utgjort en masteravhandling alene. En videre diskusjon av de dominerende ideologiske tendensene i Nasjonal Samling kunne også vært meget intressant. Hvordan fortsatte den ideologiske utviklingen etter 1937 og frem til krigen, og hvordan fremsto Nasjonal Samling ideologisk etter den tyske invasjonen? Desverre er dette spørsmål som jeg, eller noen andre, må ha til gode. For å levere oppgaven på normert tid har det vært nødvendig å begrense omfanget av oppgaven. -

Ethnologia Scandinavica 2019

Contents Papers vetenhet i Gamlakarleby socken 1740‒1800. Rev. by Mikkel Venborg Pedersen 3 Editorial. By Lars-Eric Jönsson 199 Religion as an Equivocal Praxis in the European 5 Tales from the Kitchen Drawers. The Micro- Union. Helene Rasmussen Kirstein, Distinktio- physics of Modernities in Swedish Kitchens. By nens tilsyneladende modsætning. En etnologisk Håkan Jönsson undersøgelse af religionsbegrebets flertydighed 22 Reading the Reindeer. New Ways of Looking at som mulighedsbetingelse for europæiske kirkers the Reindeer and the Landscape in Contemporary position i EU’s demokrati. Rev. by Sven-Erik Husbandry. By Kajsa Kuoljok Klinkmann 40 Sensations of Arriving and Settling in a City. 201 Fieldwork into Fandom. Jakob Löfgren, …And Young Finnish Rural Out-migrants’ Experiences Death proclaimed ‘Happy Hogswatch to all and with Moving to Helsinki. By Lauri Turpeinen to all a Good Night.’ Intertext and Folklore in 56 Returnees’ Cultural Jetlag. Highly Skilled Profes- Discworld-Fandom. Rev. by Tuomas Hovi sionals’ Post-Mobility Experiences. By Magnus 204 Fleeting Encounters with Birds and Birdwatchers. Öhlander, Katarzyna Wolanik Boström & Helena Elin Lundquist, Flyktiga möten. Fågelskådning, Pettersson epistemisk gemenskap och icke-mänsklig karis- 70 Danish Gentlemen around 1900. Ideals, Culture, ma. Rev. by Carina Sjöholm Dress. By Mikkel Venborg Pedersen 206 Finnish War Children in Sweden. Barbara Matts- 92 Narrating and Relating to Ordinariness. Experi- son, A Lifetime in Exile. Finnish War Children in ences of Unconventional Intimacies in Contem- Sweden after the War. An Interview Study with a porary Europe. By Tone Hellesund, Sasha Rose- Psychological and Psychodynamic Approach. neil, Isabel Crowhurst, Ana Cristina Santos & Rev. by Florence Fröhlig Mariya Stoilova 209 Work-Life Orientations for Ethnologists. -

Tyranny Could Not Quell Them

ONE SHILLING , By Gene Sharp WITH 28 ILLUSTRATIONS , INCLUDING PRISON CAM ORIGINAL p DRAWINGS This pamphlet is issued by FOREWORD The Publications Committee of by Sigrid Lund ENE SHARP'S Peace News articles about the teachers' resistance in Norway are correct and G well-balanced, not exaggerating the heroism of the people involved, but showing them as quite human, and sometimes very uncertain in their reactions. They also give a right picture of the fact that the Norwegians were not pacifists and did not act out of a sure con viction about the way they had to go. Things hap pened in the way that they did because no other wa_v was open. On the other hand, when people acted, they The International Pacifist Weekly were steadfast and certain. Editorial and Publishing office: The fact that Quisling himself publicly stated that 3 Blackstock Road, London, N.4. the teachers' action had destroyed his plans is true, Tel: STAmford Hill 2262 and meant very much for further moves in the same Distribution office for U.S.A.: direction afterwards. 20 S. Twelfth Street, Philadelphia 7, Pa. The action of the parents, only briefly mentioned in this pamphlet, had a very important influence. It IF YOU BELIEVE IN reached almost every home in the country and every FREEDOM, JUSTICE one reacted spontaneously to it. AND PEACE INTRODUCTION you should regularly HE Norwegian teachers' resistance is one of the read this stimulating most widely known incidents of the Nazi occu paper T pation of Norway. There is much tender feeling concerning it, not because it shows outstanding heroism Special postal ofler or particularly dramatic event§, but because it shows to new reuders what happens where a section of ordinary citizens, very few of whom aspire to be heroes or pioneers of 8 ~e~~ 2s . -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 199

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 199 Secession och diplomati Unionsupplösningen 1905 speglad i korrespondens mellan UD, beskickningar och konsulat Redaktörer: Evert Vedung, Gustav Jakob Petersson och Tage Vedung 2017 © Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala och redaktörerna 2017 Omslagslayout: Martin Högvall Omslagsbild: Tage Vedung, Evert Vedung ISSN 0346-7538 ISBN 978-91-513-0011-5 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821) Tryckt i Sverige av DanagårdLiTHO AB 2017 Till professor Stig Ekman Till minnet av docent Arne Wåhlstrand Inspiratörer och vägröjare Innehåll Förord ........................................................................................................ ix Secession och diplomati – en kronologi maj 1904 till december 1905 ...... 1 Secession och diplomati 1905 – en inledning .......................................... 29 Åtta bilder och åtta processer: digitalisering av diplomatpost från 1905 ... 49 A Utrikesdepartementet Stockholm – korrespondens med beskickningar och konsulat ............................................................. 77 B Beskickningar i Europa och USA ................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Berlin ...................................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Bryssel/Haag ......................................................... 197 Beskickningen i Konstantinopel ....................................................... 202 Beskickningen -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

Page 01 June 06.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Thursday 6 June 2013 27 Rajab 1434 - Volume 18 Number 5722 Price: QR2 QE to woo Nadal, Djokovic more foreign to clash in French investment Open semis Business | 21 Sport | 32 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Bahrain probe Qatar Foundation signs MoU OPINION Qaradawi, Hezbollah and sectarian war into Hezbollah his Tweek Germany warned against business links arming Syrian rebels on the ground Other GCC nations urged to follow suit that it might lead Khalid Al Sayed DOHA: Some seven years after the whole region,” said a commen- to sectar- EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Hezbollah and its leader Sayyed tator on Alarabia.net yesterday. ian war, Hassan Nasrallah were cel- “If Arab leaders want stability but those watching the ebrated as heroes in the GCC in their countries, they must ban Syrian uprising might have region and the rest of the Arab Hezbollah’s activities in their ter- noticed that the sectarian world for their victory over ritories.” Another commentator war has already started — Israel, the tables seem to be writing on the web portal called with Hezbollah chief Hassan turning against the militant for a ban on Shias in (Arab and Nasrallah’s speech. He openly outfit as it intervenes in Syria GCC states) so “they abandon declared his support for the and goes on a killing spree their pro-Iran agenda”. Bashar Al Assad regime and against Sunni rebels. Yet another suggested that if sent his people to Syria to Just days after the GCC sec- the GCC states boycott Hezbollah, fight alongside Assad’s forces, retary-general, Abdullatif Al “100s of thousands of Lebanese H H Sheikha Moza bint Nasser and Prince Charles witnessing the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding declaring that he would not Zayani, condemned Hezbollah for Shia based in the region would be between Qatar Foundation and the Prince of Wales’ Charitable Foundation that will focus on developing give terrorists a chance to interfering in Syria, Bahrain yes- driven away. -

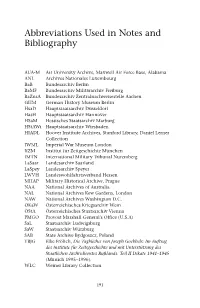

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk A

Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway By Dean N. Krouk A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair Professor Linda Rugg Professor Karin Sanders Professor Dorothy Hale Spring 2011 Abstract Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair This study examines selections from the work of three modernist writers who also supported Norwegian fascism and the Nazi occupation of Norway: Knut Hamsun (1859- 1952), winner of the 1920 Nobel Prize; Rolf Jacobsen (1907-1994), Norway’s major modernist poet; and Åsmund Sveen (1910-1963), a fascinating but forgotten expressionist figure. In literary studies, the connection between fascism and modernism is often associated with writers such as Ezra Pound or Filippo Marinetti. I look to a new national context and some less familiar figures to think through this international issue. Employing critical models from both literary and historical scholarship in modernist and fascist studies, I examine the unique and troubling intersection of aesthetics and politics presented by each figure. After establishing a conceptual framework in the first chapter, “Unsettling Modernity,” I devote a separate chapter to each author. Analyzing both literary publications and lesser-known documents, I describe how Hamsun’s early modernist fiction carnivalizes literary realism and bourgeois liberalism; how Sveen’s mystical and queer erotic vitalism overlapped with aspects of fascist discourse; and how Jacobsen imagined fascism as way to overcome modernity’s culture of nihilism. -

Central Banks Under German Rule During World War II

2012 | 02 Working Paper Norges Bank’s bicentenary project Central banks under German rule during World War II: The case of Norway Harald Espeli Working papers fra Norges Bank, fra 1992/1 til 2009/2 kan bestilles over e-post: [email protected] Fra 1999 og fremover er publikasjonene tilgjengelig på www.norges-bank.no Working papers inneholder forskningsarbeider og utredninger som vanligvis ikke har fått sin endelige form. Hensikten er blant annet at forfatteren kan motta kommentarer fra kolleger og andre interesserte. Synspunkter og konklusjoner i arbeidene står for forfatternes regning. Working papers from Norges Bank, from 1992/1 to 2009/2 can be ordered by e-mail: [email protected] Working papers from 1999 onwards are available on www.norges-bank.no Norges Bank’s working papers present research projects and reports (not usually in their final form) and are intended inter alia to enable the author to benefit from the comments of colleagues and other interested parties. Views and conclusions expressed in working papers are the responsibility of the authors alone. ISSN 1502-8143 (online) ISBN 978-82-7553-662-2 (online) Central banks under German rule during World War II: The case of Norway1 Harald Espeli Until the German invasion of Norway 9 April 1940 the Norwegian central bank had been one of the most independent in Western Europe. This article investigates the agency of the Norwegian central bank during the German occupation and compares it with central banks in other German occupied countries. The Norwegian central bank seems to have been more accommodating to German wishes and demands than the central banks in other German occupied countries in Western Europe.