OMPG Library Edition.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marsland Class III Cultural Resource Investigation (April 28, 2011)

NRC-054B Submitted: 5/8/2015 I AR CAD IS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I I I I I I I I Figure4. Project overview in Section 35 T30N R51W, facing south. Photograph taken by N. Graves, on 12/02/2010. I I I I I I I I Figure 5. Project overview in Section 2 T29N R51W, facing northeast. Photograph taken by A. Howder on 12/03/2010. I 4 I -1- I ARCADJS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I I I I I I I I I Figure 6. Project overview in Section 1 T29N R51W, facing southeast. Photograph taken by A. Howder on 12/04/2010. I I I I I I I I F. Topographic Map 5 I -2- I AR CAD IS Marsland Expansion Cultural Inventory I V. Environmental Setting I A. Present Environment 1. General Topographic Features I The MEAUP is located in the northern Nebraska Panhandle roughly 10 to 12 miles south of Crawford, Nebraska and five miles northeast of Marsland, Nebraska. This portion of the Nebraska Panhandle is dominated topographically by the Pine Ridge escarpment, a rugged, stony region of forested buttes and I deep canyons that divides the High Plains to the south from the Missouri Plateau to the north. The project area straddles the southernmost boundary of the Pine Ridge escarpment and another distinct topographic region to the south, the Dawes Table lands. Taken together, these regions form a unique local mosaic of I topography, geology, and habitat within the project area. I 2. Project Area a. Topography I The Pine Ridge escarpment covers more than one thousand square miles across far eastern Wyoming, northern Nebraska and extreme southern South Dakota (Nebraska State Historical Society 2000). -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Fidler in Context

TABLE OF CONTENTS acknowledgements vii introduction Fidler in Context 1 first journal From York Factory to Buckingham House 43 second journal From Buckingham House to the Rocky Mountains 95 notes to the first journal 151 notes to the second journal 241 sources and references 321 index 351 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION FIDLER IN CONTEXT In July 1792 Peter Fidler, a young surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, set out from York Factory to the company’s new outpost high on the North Saskatchewan River. He spent the winter of 1792‐93 with a group of Piikani hunting buffalo in the foothills SW of Calgary. These were remarkable journeys. The river brigade travelled more than 2000 km in 80 days, hauling heavy loads, moving upstream almost all the way. With the Piikani, Fidler witnessed hunts at sites that archaeologists have since studied intensively. On both trips his assignment was to map the fur-trade route from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountains. Fidler kept two journals, one for the river trip and one for his circuit with the Piikani. The freshness and immediacy of these journals are a great part of their appeal. They are filled with descriptions of regional landscapes, hunting and trading, Native and fur-trade cultures, all of them reflecting a young man’s sense of adventure as he crossed the continent. But there is noth- ing naive or spontaneous about these remarks. The journals are transcripts of his route survey, the first stages of a map to be sent to the company’s head office in London. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Bear in the Footprint: Using Ethnography to Interpret Archaeological Evidence of Bear Hunting and Bear Veneration in the Northern Rockies

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES Michael D. Ciani The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ciani, Michael D., "THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4218. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4218 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BEAR IN THE FOOTPRINT: USING ETHNOGRAPHY TO INTERPRET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF BEAR HUNTING AND BEAR VENERATION IN THE NORTHERN ROCKIES By Michael David Ciani B.A. Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2012 A.S. Historic Preservation, College of the Redwoods, Eureka, CA, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Cultural Heritage The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Douglas H. MacDonald, Chair Anthropology Dr. Anna M. Prentiss Anthropology Dr. Christopher Servheen Forestry and Conservation Ciani, Michael, M.A., May 2014 Major Anthropology The Bear in the Footprint: Using Ethnography to Interpret Archaeological Evidence of Bear Hunting and Bear Veneration in the Northern Rockies Chairperson: Dr. -

Archaeological Investigations at the Dog Child Site (Fbnp-24): an Evaluation of Mummy Cave Subsistence Patterns

Archaeological Investigations at the Dog Child Site (FbNp-24): An Evaluation of Mummy Cave Subsistence Patterns A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Jody Raelene Pletz Copyright Jody Raelene Pletz, December 2010. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology 55 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B1 i Abstract The Dog Child site is a multi-component archaeological site located within Wanuskewin Heritage Park, approximately three kilometres from the City of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. -

RESEARCH Mffikflm DE RECHERCHES

RESEARCH MffiKFlM DE RECHERCHES NATIONAL HISTORIC PARKS DIRECTION DES PARCS AND ET DES SITES BRANCH LIEUX HISTORIQUES NATIONAUX No. 45 February 1977 Fire in the Beaver Hills Introduction Before proceeding with an historical investigation of fire and its possible historical impact upon the Beaver Hills landscape, it is necessary to outline the approach to this subject. First of all, there is a considerable body of literature by geographers, biologists and other scholars who have studied fire in relation to the grasslands and savannas of the world. *• Nevertheless, some important ques tions remain. What effects have fire had on vegetation, flora, and other aspects of landscape, including man him self? What relationships have existed between fires, climate and man? Very little relevant research on such questions has been undertaken utilizing the extensive historical literature on the northern plains of Western Canada and the American West.2 The only scholarly study for the pre-1870 period is a survey of the causes and effects of fire on the northern grasslands of Canada and the United States written by J.G. Nelson and R.E. England.3 It pro vides a broad overview of the impact of fire upon the prairie landscape. For an assessment of the impact of fire in the Beaver Hills area the early writings of the agents of the fur trade in the Hudson's Bay Company archives must be examined. There were several fur trading posts established within a hundred-mile radius of the Beaver Hills area after 1790. Unfortunately, few records relating to the North West Company's operations have survived.^ For information on posts such as Fort Augustus, built at the mouth of the Sturgeon river in 1795, the historian depends primarily upon references made by servants of the Hudson's Bay Company. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Information Package Watercourse

Information Package Watercourse Crossing Management Directive June 2019 Disclaimer The information contained in this information package is provided for general information only and is in no way legal advice. It is not a substitute for knowing the AER requirements contained in the applicable legislation, including directives and manuals and how they apply in your particular situation. You should consider obtaining independent legal and other professional advice to properly understand your options and obligations. Despite the care taken in preparing this information package, the AER makes no warranty, expressed or implied, and does not assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. For the most up-to-date versions of the documents contained in the appendices, use the links provided throughout this document. Printed versions are uncontrolled. Revision History Name Date Changes Made Jody Foster enter a date. Finalized document. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. Alberta Energy Regulator | Information Package 1 Alberta Energy Regulator Content Watercourse Crossing Remediation Directive ......................................................................................... 4 Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 4 How the Program Works ....................................................................................................................... -

G/F1z@/ F Inancial S Tateme Nt

COUNTYOF PONOKANo. 3 COUNTYCOUNCIL MEETING 58 10‘? July 121 1968 A meeting of the County Council was held in the Council Chambers at Ponoka on Friday July 12th, l968, with Reeve I. E. Davies presiding and the following Councillors present: A. C. Boman, F. E. Palechek, R. C. Jensen, G. E. Ferguson, E. Solberg and L. L. Soderberg. The agenda was as follows: 1. Minutes of June lhth, 1968., 2. Business arising from the minutes. Report on Ponoka nuisance ground site. Report on Bear Hills draining project meeting June 17. Water and sewer installation in Public Works shop, Rimbey. Drainage investigation NW 1 and NE 2—h2—23—Whand NE l3“LL3-23—WLL. Assessment of claim for damages re pound case. Nuisance ground, Eureka school grounds. 3. Roads and Highways . a) Lease of road allowance W/SW28-111-2-W5. b) Acknowledgement of letter of authority to construct a road in NW 3, SE 9-LL2—3—W5. By—Law for numbering streets and avenues in the Hamlet of Bluffton. Summary of bridge inventory on Blindman River and recommendations . Summary of bridge inventory on Medicine River and recommendations . Bridge authorizations. Compensation for fence removal and re-erection I NE 2l, SW 22~L;2—3-W5. V Railway Crossing — Section l9—}.L2-25—W}.L. Notice of change in regulations in new subdivisions. Lease of road allowance W/SW29—LL2-2).;-Wh. Battle River Planning Commission. NWl9—LL2—-25—W)l- McCoy, Berg. SE 2h—Ly.2-26—Wl1- Berg, Courser. SW 28—h2—2S~W)4- E, W. -

Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College Version June 20, 2012

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version June 20, 2012 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation. The articles use a variety of measurements. Some useful conversions: 1”=2.54 -

A Quantitative Analysis of Promontory Cave 1: an Archaeological Study on Population Size, Occupation Span, Artifact Use-Life, and Accumulation

A Quantitative Analysis of Promontory Cave 1: An Archaeological Study on Population Size, Occupation Span, Artifact Use-life, and Accumulation by Jennifer Hallson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology University of Alberta © Jennifer Hallson, 2017 Abstract Promontory Cave 1 on Great Salt Lake, Utah exhibits an incredible level of preservation rarely seen at archaeological sites. The high proportion of perishable materials provides a unique opportunity to study cultural remains that are usually lost to taphonomic processes. Extensive radiocarbon dating has defined a narrow occupation period of ca. 1250-1290 CE (Ives et al. 2014) and the bounded space of the cave allows for confident estimations of the total number of artifacts present. I have completed quantitative analyses that use several methods to study Cave 1 and its inhabitants, including: artifact density, three-dimensional modeling, proportional calculations, accumulation equations, and statistical equations. Archaeologists know surprisingly little about the rates at which artifacts enter the archaeological record and my analyses examine this factor along with related variables such as use-life and accumulation with the above methods. The above methods also allow for inferences to be made on population size, population composition, and occupation span and frequency. Quantitative analyses of the Promontory Cave 1 assemblage can be linked directly to the exploration of Dene migration southward from Canada, as artifacts found in the cave point towards an identity of Apachean ancestors during their migration south. This research also has the potential for much broader application in archaeological investigations by increasing our awareness of what is usually missing; organic artifacts by far dominated past life but are often forgotten during site analysis. -

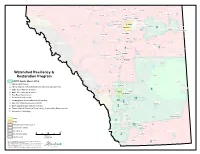

Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Program Maps

VU32 VU33 VU44 VU36 V28A 947 U Muriel Lake UV 63 Westlock County VU M.D. of Bonnyville No. 87 18 U18 Westlock VU Smoky Lake County 28 M.D. of Greenview No. 16 VU40 V VU Woodlands County Whitecourt County of Barrhead No. 11 Thorhild County Smoky Lake Barrhead 32 St. Paul VU County of St. Paul No. 19 Frog Lake VU18 VU2 Redwater Elk Point Mayerthorpe Legal Grande Cache VU36 U38 VU43 V Bon Accord 28A Lac Ste. Anne County Sturgeon County UV 28 Gibbons Bruderheim VU22 Morinville VU Lamont County Edson Riv Eds er on R Lamont iver County of Two Hills No. 21 37 U15 I.D. No. 25 Willmore Wilderness Lac Ste. Anne VU V VU15 VU45 r Onoway e iv 28A S R UV 45 U m V n o o Chip Lake e k g Elk Island National Park of Canada y r R tu i S v e Mundare r r e Edson 22 St. Albert 41 v VU i U31 Spruce Grove VU R V Elk Island National Park of Canada 16A d Wabamun Lake 16A 16A 16A UV o VV 216 e UU UV VU L 17 c Parkland County Stony Plain Vegreville VU M VU14 Yellowhead County Edmonton Beaverhill Lake Strathcona County County of Vermilion River VU60 9 16 Vermilion VU Hinton County of Minburn No. 27 VU47 Tofield E r i Devon Beaumont Lloydminster t h 19 21 VU R VU i r v 16 e e U V r v i R y Calmar k o Leduc Beaver County m S Leduc County Drayton Valley VU40 VU39 R o c k y 17 Brazeau County U R V i Viking v e 2A r VU 40 VU Millet VU26 Pigeon Lake Camrose 13A 13 UV M U13 VU i V e 13A tt V e Elk River U R County of Wetaskiwin No.