Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Fidler in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota North Shore Trout Stream Map Index

Trout Angling Opportunities in NE Minnesota Angling Access Table of Trout Lakes Angling Easements Trout lakes are listed by Area Fisheries Office. The DNR purchases easements from private •Designated trout waters are marked with an asterisk(*) landowners that are willing to provide permanent •Stocked species are listed in bold type fishing access to the public. Easement corridors are •BWCAW lakes (entirely or partly within) are in italics strips of land along a stream 66 feet from the stream’s and underlined. centerline in either direction. Tan signs mark the start •Additional regulations on designated trout lakes: refer and end of many streamside easements, however, signs to the current Minnesota Fishing Regulations book. are sometimes missing so anglers should use these •Lakes in red have no winter trout season. maps to be sure they are on an easement. Hunting and •Lakes in brown have special regulations: other recreational activities in easement areas are not •Catch-and-release only. permitted without the landowner’s permission. •Artificial lures and flies with a single hook only. •Use and possession of bait is prohibited. Accessible Fishing Piers and Platforms •Closed to winter fishing. •Abbreviations: Fishing locations with fishing piers or platforms •BKT=brook trout suitable for wheelchair users are found at the following •BNT=brown trout trout waters in northeast Minnesota: •LAT=lake trout •RBT=rainbow trout Lake Name Nearest City •SPT=splake Hogback Lake Isabella Aitkin Trout Species Map # Blue Lake RBT 9a Miner’s Lake Ely Loon -

Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview

PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Proponent – Manitoba Infrastructure ...................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Contact Information ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Legal Entity .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.3 Corporate and Management Structures ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.4 Corporate Policy Implementation ...................................................................... 1-2 1.1.5 Document Preparation ....................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Project Overview .............................................................................................................. 1-3 1.2.1 Project Components ......................................................................................... 1-11 1.2.2 Project Phases and Scheduling ......................................................................... 1-11 1.2.3 The East Side Transportation Initiative ............................................................. 1-14 1.3 Project Location ............................................................................................................ -

PRESENTATIONS CANOECOPIA PRESENTATIONS for 2020 We Proudly Offer up a Cornucopia of Canoecopia Speakers & Topics

PRESENTATIONS CANOECOPIA PRESENTATIONS FOR 2020 We proudly offer up a cornucopia of Canoecopia speakers & topics. Christopher Amidon Paddling Isle Royale National Park Sat 1:30p, Quetico Sun 2:30p, Superior Isle Royale National Park offers unique opportunities for paddling in and around a wilderness island in Lake Superior. The challenges facing paddlers are many, from the logistics of transporting paddling equipment to the unpredictable and cold waters of Lake Superior. Join Ranger Chris Amidon to explore the paddling options and obstacles of Isle Royale National The Aluminum Chef Competition Park. Brought to you by MSR Sat 4:30p, Quetico Gregory Anderson Once again, our three Aluminum Chefs will test their camp culinary The Science of Waves skills against each other in true outdoor style. Kevin Callan returns as Fri 6:30p, Loon our unstoppable emcee in this fast-paced event. Woods-woman, Mona Have you ever wondered why wave fronts Gauthier and former park ranger Marty Koch go up against local chef end up parallel to the beach? How do shoals Luke Zahm of the Driftless Cafe in Viroqua, WI. Using MSR stoves create larger waves? Why do waves bend and cook kits, and a pantry of simple ingredients you might have on around obstacles? Understanding waves will your next camping trip (donated by the Driftless Cafe), our chefs will help you manage the surf zone and make you compete for the best appetizer, entree, and dessert. Come join the fun a better paddler, whether you want to avoid a - you could be one of the judges from the audience who will determine pounding or to catch the ride of your life. -

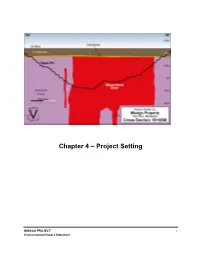

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

Samuel Hearne

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN A YANKEE IN CANADA: SAMUEL HEARNE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY People Mentioned in A Yankee in Canada “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX SAMUEL HEARNE SAMUEL HEARNE “A YANKEE IN CANADA”: I got home this Thursday evening, having spent just one week in Canada and travelled eleven hundred miles. The whole expense of this journey, including two guidebooks and a map, which cost one dollar twelve and a half cents, was twelve dollars seventy five cents. I do not suppose that I have seen all British America; that could not be done by a cheap excursion, unless it were a cheap excursion to the Icy Sea, as seen by Hearne or McKenzie, and then, no doubt, some interesting features would be omitted. I wished to go a little way behind that word Canadense, of which naturalists make such frequent use; and I should like still right well to make a longer excursion on foot through the wilder parts of Canada, which perhaps might be called Iter Canadense. SAMUEL HEARNE ALEXANDER MACKENZIE HDT WHAT? INDEX SAMUEL HEARNE SAMUEL HEARNE 1745 February (1744, Old Style): Samuel Hearne, who would become the initial European to make an overland excursion across northern Canada to the Arctic Ocean, was born in London, England. His father was a senior engineer of the London Bridge Water Works but would die during Samuel’s early childhood. CANADA THE FROZEN NORTH NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT People Mentioned in A Yankee in Canada “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX SAMUEL HEARNE SAMUEL HEARNE 1756 The beginning of the Seven Year War (Prussia and Britain versus France, Austria, and Russia), which, as its name implies, would not come to its completion until 1763. -

The Story of the Trapper. Viišjohn Colter, the Free Trapper

THE STORY OF THE TRAPPER VII.—JOHN COLTER, THE FREE TRAPPER By A. C. LAUT 1. ARLY one morning two white man suffered heavy loss owing to Colter’s prowess. slipped out of their sequestered cabin That made the Blackfeet sworn enemies to E built in hiding of the hills at the head- Colter. waters of the Missouri. Under covert of Turning off the Jefferson, the trappers brushwood lay a long, odd-shaped canoe, headed their canoe up a side stream, prob- sharp enough at the prow to cleave the nar- ably one of those marshy reaches where bea- rowest waters between rocks, so sharp that vers have formed a swamp by damming up French voyageurs gave this queer craft the the current of a sluggish stream. Such quiet name—“canot à bec d’esturgeon,” that is, a waters are favorite resorts for beaver and canoe like the nose of a sturgeon. This Amer- mink and marten and pekan. Setting their ican adaptation of the Frenchman’s craft traps only after nightfall, the two men could was not a birch bark. That would be too not possibly have put out more than forty frail to essay the rock-ribbed cañons of the or fifty. Thirty traps are a heavy day’s work mountain streams. It was usually a common for one man. Six prizes out of thirty are dug-out, hollowed from a cottonwood, or considered a wonderful run of luck; but the other light timber, with such an angular nar- empty traps must be examined as carefully row prow it could take the sheerest dip as the successful ones. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Genetic Population Structure of Walleye (Sander vitreus) in Northern Alberta and Application to Species Management by Lindsey Alison Burke A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Systematics and Evolution Biological Sciences ©Lindsey Alison Burke Fall 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62977-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-62977-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque -

Cold Lake Health Assessment FINAL

Cold Lake Health Assessment A study under the Regional Waterline Strategy and Governance Model Development Project Prepared for: Town of Bonnyville, City of Cold Lake, and Municipal District of Bonnyville Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Ltd. Project No.: 113929476 FINAL April 7, 2017 Sign-off Sheet This document entitled Cold Lake Health Assessment was prepared by Stantec Consulting Ltd. This document entitled Cold Lake Health Assessment was prepared by Stantec Consulting Ltd. (“Stantec”) for the account of the Partnership (the “Client”). Any reliance on this document by any third party is strictly prohibited. The material in it reflects Stantec’s professional judgment in light of the scope, schedule and other limitations stated in the document and in the contract between Stantec and the Client. The opinions in the document are based on conditions and information existing at the time the document was published and do not take into account any subsequent changes. In preparing the document, Stantec did not verify information supplied to it by others. Any use which a third party makes of this document is the responsibility of such third party. Such third party agrees that Stantec shall not be responsible for costs or damages of any kind, if any, suffered by it or any other third party as a result of decisions made or actions taken based on this document. Prepared by L. Karoliina Munter, M.Sc., P.Biol. Co-authors: Seifu Guangul, Ph.D., P.Eng, D.WRE Nick De Carlo, B.Sc., P.Biol., QWSP Stuart Morrison, Dip. B.Sc. Greg Schatz, M.Sc., P.Biol Reviewed by John Orwin, Ph.D., P.Geo. -

RESEARCH Mffikflm DE RECHERCHES

RESEARCH MffiKFlM DE RECHERCHES NATIONAL HISTORIC PARKS DIRECTION DES PARCS AND ET DES SITES BRANCH LIEUX HISTORIQUES NATIONAUX No. 45 February 1977 Fire in the Beaver Hills Introduction Before proceeding with an historical investigation of fire and its possible historical impact upon the Beaver Hills landscape, it is necessary to outline the approach to this subject. First of all, there is a considerable body of literature by geographers, biologists and other scholars who have studied fire in relation to the grasslands and savannas of the world. *• Nevertheless, some important ques tions remain. What effects have fire had on vegetation, flora, and other aspects of landscape, including man him self? What relationships have existed between fires, climate and man? Very little relevant research on such questions has been undertaken utilizing the extensive historical literature on the northern plains of Western Canada and the American West.2 The only scholarly study for the pre-1870 period is a survey of the causes and effects of fire on the northern grasslands of Canada and the United States written by J.G. Nelson and R.E. England.3 It pro vides a broad overview of the impact of fire upon the prairie landscape. For an assessment of the impact of fire in the Beaver Hills area the early writings of the agents of the fur trade in the Hudson's Bay Company archives must be examined. There were several fur trading posts established within a hundred-mile radius of the Beaver Hills area after 1790. Unfortunately, few records relating to the North West Company's operations have survived.^ For information on posts such as Fort Augustus, built at the mouth of the Sturgeon river in 1795, the historian depends primarily upon references made by servants of the Hudson's Bay Company. -

Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada

BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers Volume 25 Volume 25 (2013) Article 6 1-1-2013 Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada Karlis Karklins Gary F. Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Karklins, Karlis and Adams, Gary F. (2013). "Beads from the Hudson's Bay Company's Principal Depot, York Factory, Manitoba, Canada." BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 25: 72-100. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol25/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEADS FROM THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY’S PRINCIPAL DEPOT, YORK FACTORY, MANITOBA, CANADA Karlis Karklins and Gary F. Adams There is no other North American fur trade establishment whose half a dozen times in two separate international conflicts. longevity and historical significance can rival that of York Factory. It witnessed a naval engagement and suffered three direct Located in northern Manitoba, Canada, at the base of Hudson Bay, attacks. The factory was rebuilt seven times and was the it was the Hudson’s Bay Company’s principal Bay-side trading base of operations for such fur trade personalities as Pierre post and depot for over 250 years. -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

SAB 015 1994 P14-26 the Unlikely 18Th Century Naturalists Of

Studies in Avian Biology No. 15: 14-26, 1994. THE UNLIKELY 18TH CENTURY NATURALISTS OF HUDSON’S BAY C. STUART HOUSTON Abstract. The Hudson’s Bay Territory, which included the entire drainage basin west to the Rocky Mountains, although one of the most thinly occupied areas in all of North America, was second only to South Carolina as the North American locality which contributed the most type specimens of birds. The collectors, fur traders ofthe Hudson’s Bay Company, were Alexander Light, James Isham, Thomas Hutchins, Humphrey Marten, Andrew Graham, and Samuel Heame. My researches in the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives and the Royal Society library have solved the long-standing confusion about the relative contributions of Andrew Graham and Thomas Hutchins to the Observationspublished in 1969 by the Hudson’s Bay Record Society. I have transcribed for publication the separate original “journals” of Graham and Hutchins and have compiled the largest dictionary of Cree Indian names of birds. Isham and Graham collected the most type specimens. Heame was the best naturalist. Hutchins, the medical doctor and best scientist, was the only one to have a taxon named for him. Key Words: Hudson’s Bay Territory; Alexander Light; James Isham; Humphrey Marten; Andrew Graham; Samuel Hearne; Thomas Hutchins; type specimens. From the Hudsons’ Bay Territory, one of front of scientific ornithology and taxono- the most thinly occupied areas in all of North my. America, came improbable but extremely Severn, with a year-round population of important contributions to 18th-Century 20 white fur traders, and Albany with 33, ornithology.