Geographical Pattern of Muslim Population in India, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Ladakh Travels Far and Fast

LADAKH TRAVELS FAR AND FAST Sat Paul Sahni In half a century, Ladakh has transformed itself from the medieval era to as modern a life as any in the mountainous regions of India. Surely, this is an incredible achievement, unprecedented and even unimagin- able in the earlier circumstances of this landlocked trans-Himalayan region of India. In this paper, I will try and encapsulate what has happened in Ladakh since Indian independence in August 1947. Independence and partition When India became independent in 1947, the Ladakh region was cut off not only physically from the rest of India but also in every other field of human activity except religion and culture. There was not even an inch of proper road, although there were bridle paths and trade routes that had been in existence for centuries. Caravans of donkeys, horses, camels and yaks laden with precious goods and commodities had traversed the routes year after year for over two millennia. Thousands of Muslims from Central Asia had passed through to undertake the annual Hajj pilgrimage; and Buddhist lamas and scholars had travelled south to Kashmir and beyond, as well as towards Central Tibet in pursuit of knowledge and religious study and also for pilgrimage. The means of communication were old, slow and outmoded. The postal service was still through runners and there was a single telegraph line operated through Morse signals. There were no telephones, no newspapers, no bus service, no electricity, no hospitals except one Moravian Mission doctor, not many schools, no college and no water taps. In the 1940s, Leh was the entrepôt of this part of the world. -

![Download Complete [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6761/download-complete-pdf-896761.webp)

Download Complete [PDF]

Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Journal of Defence Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.idsa.in/journalofdefencestudies Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Operations in 1965: Weaknesses and Strengths Arjun Subramaniam To cite this article: Arjun Subramaniam (201 5): Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Op erations in 1965: Weaknesses and Strengths, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3 July-September 2015, pp. 95-113 URL http://idsa.in/jds/9_3_2015_CriticalAnalysisofPakistaniAirOperationsin1965.html Please Scroll down for Article Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.idsa.in/termsofuse This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re- distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India. Critical Analysis of Pakistani Air Operations in 1965 Weaknesses and Strengths Arjun Subramaniam* This article tracks the evolution of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) into a potent fighting force by analysing the broad contours of joint operations and the air war between the Indian Air Force (IAF) and PAF in 1965. Led by aggressive commanders like Asghar Khan and Nur Khan, the PAF seized the initiative in the air on the evening of 6 September 1965 with a coordinated strike from Sargodha, Mauripur and Peshawar against four major Indian airfields, Adampur, Halwara, Pathankot and Jamnagar. -

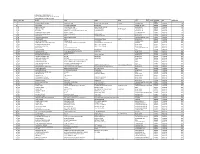

Jamna Auto Industries Ltd List of Shareholders As on 23-03-18 for Tranfer to Iepf Account Sr.No Folio No Name Add1 Add2 Add3

JAMNA AUTO INDUSTRIES LTD LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS AS ON 23-03-18 FOR TRANFER TO IEPF ACCOUNT SR.NO FOLIO_NO NAME ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 CITY STATE COUNTRYPINCODE Type SHR230318 Total 1 7 KULDEEP SINGH BHATIA KOTHI NO 1768 PHASE 3 B-II SAS NAGAR MOHALI CHANDIGARH 000000 PHYSICAL 100 2 8 RAJ KUMAR K R STEEL PRODUCTS BURIA GATE JAGADHRI (HRY) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 3 10 SANTOSH AHUJA C/O COL VK AHUJA NEW BHOPAL TEXTILE BHOPAL (M P) 462001 PHYSICAL 100 4 13 JASWANT KAUR C/O S SURJEET SINGH CHEEMA HOUSE PREM NAGAR PATIALA (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 5 14 G S MANN MANN VILLA 22 NEW OFFICER COLONY STADIUM ROAD PATIALA (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 6 17 HARMINDER PAUL SINGH MODEL TOWN JALANDHAR (P B) 000000 PHYSICAL 100 7 18 HARDEV BAHADUR SINGH AJMAL KHAN ROAD KAROL BAGH NEW DELHI 000000 PHYSICAL 100 8 20 SARLADEVI E-255 GREATER KAILASH NEW DELHI 110048 PHYSICAL 100 9 22 MADHU BHATNAGAR PAPER MILL COLONY YAMUNA NAGAR (HRY.) 135001 PHYSICAL 100 10 26 KANTA SOBTI A-90 GUJRAWALA TOWN PART - I NEW DELHI 000000 PHYSICAL 100 11 121 LAJPAT RAI CHOPRA HOUSE NO 15 SECTOR-8A CHANDIGARH 000000 PHYSICAL 6000 12 155 BHAGWAN DAS L MOLCHANDANI C/O MODERN TRADING CO (BOMBAY) FATCH MANZIL OPERA HOUSE MUMBAI 400001 PHYSICAL 3000 13 180 GURMINDER KAUR DILER 17/9 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 PHYSICAL 2000 14 187 RAVINDER KAUR DILER 17/9 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 PHYSICAL 2000 15 267 VERA SINGH VILLAGE AMADALPUR JAGADHRI (HARYANA) 000000 PHYSICAL 3000 16 286 ASHOK KUMAR LP 32 A MRURAYA ENCLAVE PITAM PURA DELHI 110034 PHYSICAL 2500 17 308 CHAMAN SINGH C-187 MANSAROVER GARDEN -

Answered On:27.07.2000 Gallantary Awards to Fighters of Kargil Conflict Simranjit Singh Mann

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEFENCE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:667 ANSWERED ON:27.07.2000 GALLANTARY AWARDS TO FIGHTERS OF KARGIL CONFLICT SIMRANJIT SINGH MANN Will the Minister of DEFENCE be pleased to state: the total number of gallantary awards awarded to the fighters of the Kargil Conflict with full particulars of recipients? Answer MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI GEORGE FERNANDES) 300 gallantry awards have so far been awarded. The details are annexed. ANNEXURE - I REFERRED TO IN REPLY GIVEN TO LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION No. 667 FOR 27.07.2000. PARTICULARS OF THE RECIPIENTS OF GALLANTRY AWARDS AWARDED ON 15.08.1999 ONACCOUNT OF KARGIL CONFLICT LIST OF RECOMMENDED CASES OF OP VIJAY : INDEPENDENCE DAY 1999 PARAM VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-57556 LT VIKRAM BATRA, 13 JAK RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 2. IC-56959 LT MANOJ KUMAR PANDEY, 1/11 GR (POSTHUMOUS) 3. 13760533 RFN SANJAY KUMAR, 13 JAK RIF 4. 2690572 GDR YOGENDER SINGH YADAV, 18 GRENADIERS MAHA VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-45952 MAJ SONAM WANGCHUK, LADAKH SCOUTS (IW) 2. IC-51512 MAJ VIVEK GUPTA, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 3. IC-52574 MAJ RAJESH SINGH ADHIKARI, 18 GDRS (POSTHUMOUS) 4. IC-55072 MAJ PADMAPANI ACHARYA, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 5. IC-57111 CAPT ANUJ NAYYAR, 17 JAT (POSTHUMOUS) 6. IC-58396 CAPT NEIKEZHAKUO KENGURUSE, 2 RAJ RIF (POSTHUMOUS) 7 SS-37111 LT KEISHING CLIFFORD NONGRUM,12 JAK LI(POSTHUMOUS) 8. SS-37691 LT BALWAN SINGH, 18 GRENADIERS 9. 2883178 NK DIGENDRA KUMAR, 2 RAJ RIF VIR CHAKRA 1. IC-35204 COL UMESH SINGH BAWA, 17 JAT 2. IC-37020 COL LALIT RAI, 1/11 GR 3. -

Defence & Aviation

II/2017 Aerospace & Defence Review Interview with CAS Aero India 2017 : In Perspective An Advanced Hawk Vayu flies Gripen India’s Aviation Industry The Air at Yelahanka II/2017 II/2017 Aerospace & Defence Review Road map for Future An Advanced Hawk Air Enthusiasts Monami Guha Das 27 and Debaditya Das write on and IAF Fighters photograph “the beauties in the skies” at Aero India 2017. Interview with CAS Aero India 2017 : In Perspective The Air at Yelahanka An Advanced Hawk 62 Vayu flies Gripen India’s Aviation Industry The Air at Yelahanka Still, the Hawk Advanced Jet Trainer Cover : Hawk Mk.132s of the IAF’s Surya was much in evidence at Yelahanka, Kiran Formation Aerobatic Team both in the air and on the ground with (Photo courtesy IAF/HAL) HAL-built Hawk Mk.132s of the Surya Kiran Formation Aerobatic Team (SKAT) DITORIAL ANEL performing daily, even as the Advanced E P Hawk “for India and the World” had MANAGING EDITOR pride of place. The joint BAE-HAL AFS Yelahanka, where the biennial Vikramjit Singh Chopra development includes a new more powerful engine (Adour Mk.951), and Aero India international air shows have EDITORIAL ADVISOR a completely redesigned wing with been held since the 1990s, is nearing its Platinum Jubilee since its establishment. Admiral Arun Prakash leading edge slats and updated ‘combat In an exclusive interview with the Vayu, flaps’ which significantly expands the Joseph Antony recalls its chequered EDITORIAL PANEL Air Chief Marshal BS Dhanoa, Chief of aircraft’s envelope. history. Its origins lie in the early 1940s when Italian POWs were engaged to Pushpindar Singh the Air Staff IAF articulates on major thrust areas for the IAF over the next build its runways and other facilities Air Marshal Brijesh Jayal few years and comments on the road 42 Some highlights of to the time it was resurrected post Dr. -

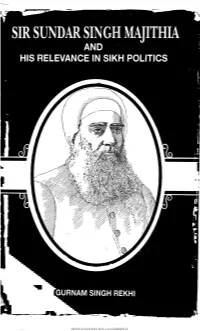

Sir Sundar Singh Majithia

'SIR SUNDAR SINGH MAJITHIA AND HIS RELEVANCE IN SIKH POLITICS' is not only a historical biography of one of the most important but mis- understood leaders who guided the destiny of his community and the nation during 50 years of its most crucial period of history before the Partition, the work also presents a study that shows a significant contradiction between the prevailing public perception and real character and integrity of a great personality. It is also an unbelievable but true • * story of a leader who was gifted with the clarity, sincerity and vision to prioritise the tasks and challenges before his community and take the requisite # steps to ensure the desired results in the field of education, employment, agriculture and religious reforms. His moderate and rational approach helped to check avoidable confrontation with the Government of the day, to the possible extent, without ever compromising his loyalty to the nation and his religious faith, which he strictly observed as a devout Sikh. The ideals and policies pursued by Sir Sundar Singh Majithia and his associates are still relevant to make this book an essential and serious study by the community and its leadership. The publication of Sir Sundar Singh Majithia and his Relevance in Sikh Politics is a thought-provoking study of the life •H and contribution of one of the most illustrious leaders of the Sikh community during the 20th century. ISBN 81-241-0617-7 Rs. 495 • f SIR SUNDAR SINGH MAJITHIA AND HIS RELEVANCE IN SIKH POLITICS SIR SUNDAR SINGH MAJITHIA AND HIS RELEVANCE IN SIKH POLITICS GURNAM SINGH REKHI HAR-ANAND PUBLICATIONS PVTLTD HAR-ANAND PUBLICATIONS PVT LTD 364-A, Chirag Delhi, New Delhi - 110017 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 91-011-5124868 Copyright © G.S. -

The History of Indian Air Force

THE HISTORY OF INDIAN AIR FORCE Cadet: Ishita Sharma HISTORY OF INDIAN AIR FORCE "And then, when I thought about joining the Air Force, flying seemed like a natural extension of the motorcycling experience. You're going faster, higher. You're operating a machine that's a lot more powerful than you are." - Duane G Carey Somewhere the journey of the Indian Airforce started when on 10th March 1910, the first time an aircraft 'took-off’ in India, when a Corsican hotelier based in Madras Giacomo D'angelis, flew a biplane he had designed. Very soon, some British army officers, who became flying enthusiasts, realized the potential of using this new invention in warfare. In 1913, Captain SD Massey of 29th Punjab Regiment, Indian Army established a military flying school at Sitapur Uttar Pradesh. The units trained here went on to serve in world war I (1914-1918). Under the unofficial name of the Indian Air corps. Indra Lal Roy (1898-1918), a scion of a wealthy Bengali zamindari family and a member of the Indian Air Corps, is considered to be the first Indian Fighter Aircraft Pilot. His nephew, Subroto Mukherjee became the first Indian to become the chief of Air Staff’ in 1954. Only four Indians are definitively known to have been military aviators in World War One. They blazed a remarkable trail for the six hundred-odd who took up that occupation in World War Two (including at least one Bollywood actor), and the three thousand-odd who serve in that role in India today. Those four pioneers were Lt Hardit Singh Malik, Lt SC Welinkar, 2Lt Errol Sen, and Flt Lt Indra Lal Roy, DFC. -

SIKH HERITAGE of NEPAL Kathmandu, Nepal EMBASSY of INDIA B.P

SIKH HERITAGE OF NEPAL SIKH HERI TAGE OF NEPAL B.P. Koirala India-Nepal Foundation EMBASSY OF INDIA Kathmandu, Nepal Gurdwara Guru Nanak Satsang, Kupondol, Kathmandu TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 • Foreword 07 • Prologue PART 1 SIKH HERITAGE OF NEPAL 12 • Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s visit to Nepal 18 • Other Forgotten Shrines of Kathmandu 26 • Maharaja Ranjit Singh meets Amar Singh in Kangra 27 • Maharani Jind Kaur’s stay in Nepal PART 2 SIKHS OF NEPAL 30 • Sikhs of Nepalgunj 32 • A Uniform Dream 35 • Sikhs of Birgunj 36 • Sikhs of Krishnanagar 38 • Sikhs of Kathmandu 38 • Pioneers in Engineering : Father-Son Engineers 40 • Trucks on Tribhuvan Highway : The Pioneers in transport 44 • Taste of Punjab 45 • Educating Young Minds 46 • Blending Kashmir and Kathmandu: A Style Guru 48 • Embracing Sikhism : The Story of Gurbakash Singh 50 • Gurdwara Guru Nanak Satsang Kupondole Kathmandu 56 • Sangat at Kupondole 70 • Langar at Kupondole 76 • 2015 Earthquake : Sikhs for Humanity 77 • Sikh Commemorative Coins issued by Nepal FOREWORD The 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev Ji provides us a special reason to celebrate the Sikh Sardar Surjit Singh Majithia, a Sikh, was the first Ambassador of India to Nepal and established Heritage of Nepal. the Embassy in 1947. His arrival and departure, by aero-plane, saw the first uses of Gauchar in Kathmandu as a landing strip. It is now Tribhuvan International Airport. Guru Nanak Dev Ji travelled through Nepal as part of his Udasis. Nanak Math in the Balaju area of Kathmandu has a peepal tree under which he is said to have meditated. -

Page6.Qxd (Page 1)

FRIDAY, MARCH 1, 2019 DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU daily Col J P Singh May 1948. Capt Kaushal, finding A Leaf from History numerically hopelessly outnum- Excelsior mportance of Ladakh does Established 1965 bered set ablaze the centuries old not start with or end at grant- wooden Bridge and gained valu- Founder Editor S.D. Rohmetra Iing an administrative Divi- able time. On May 28th, Air sional or Union Territory status. Tribute to those who saved Ladakh Commodore Mehar Singh led To understand its importance for Agency Headquarters, arrested fired with the ideals of honour of dolier of 50 rounds of ammuni- as they had none of the special- four Dakotas to land a Company India, a historical perspective of 2/4 GR at Leh with its support China and Russia actively becomes unavoidable. During Brig Ghansar Singh, the Gover- their country, devotion of duty tion and one extra rifle and two ized snow clothing and acces- nor on the night of 31 October and honour of their Battalion, month rations hoping that after sories. In Brig Sen's words, "it weapons, adequate ammunition Maharaja Pratap Singh's rule, and logistical wherewithal. This British somehow got an opportu- 1947 and massacred all non Mus- volunteer for missions unmind- sometime air supplies to Leh will called for unbound courage, lim inhabitants of the Agency. ful of the hazardous odds. 2 resume. On 16 February 1948, determination and stamina to do was unprecedented military join anti terrorism club nity to establish an Agency in Thus Gilgit-Baltistan was put Dogra had 80 soldiers from Lahul 'Leh Det' left for Sonamarg on so". -

SP's Aviation

SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION ED BUYER ONLY) ED BUYER AS -B A NDI I 100.00 ( ` aviationSHARP CONTENT FOR SHARP AUDIENCE www.sps-aviation.com vol 21 ISSUE 11 • 2018 MILITARY BUSINESS IAF Personnel AVIATION Commence Middle East Training on Scenario Apache 6 Reasons Indian Naval Why it Benefits Aviation Arm – All A Force Multiplier ANA BA Division Takes Off Modernisation of Coastal LAST Aviation WORD SPACE Eye in the Sky GSLV Mk III-D2 “Needed” Successfully Launches GSAT-29 +++ Gregory Hayes: He retains his position of Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of United Technologies. He will oversee the transition EXCITING TIMES: that includes creation of Collins Aerospace Systems in addition to the long-established engine and propulsion unit Pratt ALPHA BRAVO & Whitney, and also the divestment of the two non-aerospace business units thereby positioning UTC group RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24199 COLLINS PAGE 8 as an absolute aerospace entity. “In a country like India with limited support from the industry and market, initiating 50 years ago (in 1964) publishing magazines relating to Army, Navy and Aviation sectors without any interruption is a commendable job on the part of SP Guide“ Publications. By this, SP Guide Publications has established the fact that continuing quality work in any field would result in success.” Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India (*message received in 2014) SP's Home Ad with Modi 2016 A4.indd 1 01/06/18 12:06 PM PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jayant Baranwal SENIOR EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Air Marshal B.K. Pandey (Retd) DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR Neetu Dhulia SENIOR TECHNICAL GROUP EDITOR Lt General Naresh Chand (Retd) SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION CONTRIBUTORS India: Group Captain A.K. -

Air Power • Mr • Group Mr S • Jaishankar Air Power Air Journal of Air Power and Space Studies and Space of Air Power Journal

AIR POWER AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 13 No. 3 • Monsoon 2018 (July-September) Vol. 13 No. 3 • Monsoon 2018 • (July-September) 3 • Monsoon 13 No. Vol. contributors Mr S Jaishankar • air Marshal KK Nohwar • prof rajaram Nagappa • Mr avinash p • Ms riffath Khaji • Group captain rK Narang • Group captain JpS Bains • Ms hina pandey • dr Stuti Banerjee • Ms pooja Bhatt • Mr cyriac S pampackal ceNtre for air power StudieS, New delhi CONTENTS Editor’s Note v 1. JASJIT SINGH MEMORIAL LECTURE 1 S Jaishankar 2. AIR POWER IN JOINT OpERATIONS: PRIMACY OF JOINT TRAINING 11 KK Nohwar 3. BABUR-3—PAKISTAN’S SLCM: CAPABILITY AND LIMITATIONS 41 Rajaram Nagappa, Avinash P and Riffath Khaji 4. UAV SWARMS: CHINA’S LEAP IN CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGIES 59 RK Narang 5. CSFO LESSONS FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL WARS/CAmpAIGNS 83 JPS Bains 6. US-NORTH KOREA NUCLEAR RELATIONS: REVISITING THE PAST TO FIND POINTERS FOR THE FUTURE 105 Hina Pandey CONTENTS 7. THE NEED FOR INDIA TO BRING An ‘ASIAN PERSPECTIVE’ INTO THE ARCTIC 131 Stuti Banerjee and Pooja Bhatt 8. CLIMATE CHANGE, SEA LEVEL RISE AND TERRITORIAL SECURITY OF INDIA: TRACING THE LINK AND IMPACT 157 Cyriac S Pampackal AIR POWER Journal Vol. 13 No. 3, MONSOON 2018 (July-September) iv Editor’s NotE As we shift gear and move into the third quarter of 2018, it is time to reflect on how the ‘earth-shattering’ events of the last quarter actually panned out. The ‘trade war’ between the US and China has intensified into more than just a slug fest, with the volume of tariffs being imposed on each other’s imports reaching incomprehensible levels with each passing day.