A Soldier Remembers – a Memoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

GIPE-010149.Pdf

THE PRINCES OF INDIA [By permission of the Jlidor;a f- Albert 1lluseum THE CORONAT I O); OF AN Ii:\DI AN SOVE R E I G:\f From the :\janta Frescoes THE PRINCES OF INDIA WITH A CHAPTER ON NEPAL By SIR \VILLIAM BAR TON K.C.I.E., C.S.I. With an Introduction by VISCOUNT HAL IF AX K.G., G.C.S.l. LONDON NISBET & CO. LTD. 11 BER!'\ERS STllEET, 'W.I TO ~IY '\'!FE JJ!l.il ul Prir.:d i11 Grt~ Eri:Jill liy E11.u::, Wa:.:ctl 6- riney, W., L~ ad A>:esbury Firs! p.,.;::isilll ;,. 1;34 INTRODUCTION ITHOUT of necessity subscribing to everything that this book contains, I W am very glad to accept Sir William Barton's invitation to write a foreword to this con .. tribution to our knowledge of a subject at present occupying so large a share of the political stage. Opinion differs widely upon many of the issues raised, and upon the best way of dealing with them. But there will be no unwillingness in any quarter to admit that in the months to come the future of India will present to the people of this country the most difficult task in practical statesmanship with which thet 1hive ever been confronted. If the decision is to be a wise one it must rest upon a sound conception of the problem itself, and in that problem the place that is to be taken in the new India by the Indian States is an essential factor. Should they join the rest of India in a Federation ? Would they bring strength to a Federal Government, or weakness? Are their interests compatible with adhesion to an All-India v Vl INTRODUCTION Federation? What should be the range of the Federal Government's jurisdiction over them? These are some of the questions upon which keen debate will shortly arise. -

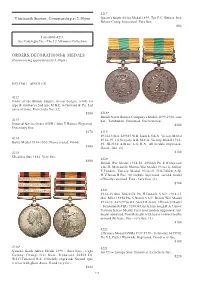

Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30Pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS

4217 Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30pm Queen’s South Africa Medal 1899. Tpr E.C.Gittoes. Imp Bshmn Contg. Impressed. Very fine. $50 Lots 4001-4211 See Catalogue78c - The J.J.Atkinson Collection ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS (Commencing approximately 3.30pm) BRITISH SINGLES 4212 Order of the British Empire, breast badges, (civil) 1st type & (military) 2nd type M.B.E. in Garrard & Co. Ltd cases of issue. Extremely fine. (2) $200 4218* British North Borneo Company’s Medal, 1899-1900 - one 4213 bar - Tambunan. Unnamed. Uncirculated. Imperial Service Order (GVR). John T.Haines. Engraved. $300 Extremely fine. $270 4219 1914-15 Star. 229583 W.H.Jones L.S.R.N. Victory Medal 4214 1914-19. J.S.Gregory A.B. M.F.A. Victory Medal 1914- Baltic Medal 1854-1855. Name erased. Good. 19. SS.2848 A.Bruce L.S. R.N. All medals impressed. $100 Good - fine. (3) 4215 $100 Khedives Star 1884. Very fine. 4220 $100 British War Medal 1914-18. 205660 Pte E.Horswood Linc.R. Mercantile Marine War Medal 1914-18. Arthur E.Youden. Victory Medal 1914-19. G.S-74024 A.Sjt H.V.Janau R.Fus. All medals impressed, second medal officially renamed. Fine - very fine. (3) $100 4221 1914-15 Star. MS-4374 Pte H.Daniels A.S.C. 1914-15 Star. MS-115956 Pte A.Brand A.S.C. British War Medal 1914-18. 24729 Pte W.L.Smith R.Scots. Efficiency Medal - Territorial (GVIR). 916634 Gnr A.Fairclough R.A. United Nations Korea Medal. First four medals impressed, last medal unnamed. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

Life Stories of the Sikh Saints

LIFE STORIES OF THE SIKH SAINTS HARBANS SINGH DOABIA Singh Brothers Antrlt•ar brr All rights of all kinds, including the rights of translation are reserved by Mrs . Harbans Singh Doabia ISBN 81-7205-143-3 First Edition February 1995 Second Edition 1998 Third Edition January 2004 Price : Rs. 80-00 Publishers : Singh Brothers • Bazar Mai Sewan, Amritsar -143 006 • S.C.O. 223-24, City Centre, Amritsar - 143 001 E-mail : [email protected] Website: www.singhbrothers.com Printers: PRINTWELL, 146, INDUSTRIAL FOCAL POINT, AMRITSAR. CONTENTS 1. LIFE STORY OF BABA NANO SINGH JI 1. Birth and Early Years 9 2. Meetings with Baba Harnam Singh Ji 10 3. Realisation 11 4. Baba Harnam Singh Ji of Bhucho 12 5. The Nanaksar Thaath (Gurdwara) 15 6. Supernatural Powers Served Baba Nand Singh Ji 17 7. Maya (Mammon) 18 8. God sends Food, Parshad and all necessary Commodities 19 9. Amrit Parchar-Khande Da Amrit 20 10. Sukhmani Sahib 21 11. Utmost Respect should be shown to Sri Guru Granth Sahib 21 12. Guru's Langar 22 13. Mandates of Gurbani 23 14. Sit in the Lap of Guru Nanak Dev Ji 26 15. Society of the True Saints and the True Sikhs 26 16. The Naam 27 17. The Portrait of Guru Nanak Dev Ji 28 18. Rosary 29 19. Pooranmashi and Gurpurabs 30 20. Offering Parshad (Sacred Food) to the Guru 32 21. Hukam Naamaa 34 22. Village Jhoraran 35 23. At Delhi 40 24. Other Places Visited by Baba Ji 41 25. Baba Ji's Spiritualism and Personality 43 26. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Gursikh Heritage

+91-9814650557 Gursikh Heritage https://www.indiamart.com/gursikh-heritage/ Deals in guru dwara models, paintings etc. About Us Dr. Sukhpal Singh, of Amritsar is from an artistic family. S Sewak Singh (G.D. Art[Lahore]), his father, was a renowned artist specilaising in landscape and nature painting. Dr Sukhpal Singh is a homeopathy physician, he attended Guru Nanakdev Homeopathy College of Ludhiana to receive his formal qualification. At a young age he showed great interest in line drawings. Gradually he progressed to model making, his first replica of The Golden Temple was built in 1976 on the Golden Temple's 400th anniversary. Dr. Singh's skill is greatly influenced by his grand-mother who was a very pious lady and a staunch devotee of Sri Guru Ram Das Ji. Dr. Sukhpal Singh believes that by displaying the replicas of various Gurdwaras and Sikh religious places at prominent places, the younger generation can be made more aware about their culture and religion. By seeing a minature of a Gurdwara one would be able to relate and appreciate with the Gurdwara or the religious place more. The replicas being to the scale are that much more realistic. All replicas carry with them facts about each Gurdwara tp help people learn about the historical background of the Gurdwara in question. Dr. Sukhpal's skills are not restricted to model making, he is also an avid painter. He paintings relate to the sikh religion. GOLDEN TEMPLE: Golden temple the holiest and highest shrine for Sikhs around the world The Harminder Sahib (meaning Temple of God) is also commonly known as the Golden Temple.. -

Sr. No. AMRITSAR Year 2012-13 Year 2013-14 Year 2014-15 Year 2015

COMMTTEE WISE Toria ARRIVAL In Quintles (Arrival of Toria ) Sr. AMRITSAR Year Year Year Year Year Year Year No. 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 1 Amritsar 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Gehri 58 8 0 33 0 0 0 3 Rayya 0 5 0 5 0 0 0 4 Mehta 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 Majitha 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 Chowgawan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 Ajnala 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 Attari 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 TOTAL 58 13 0 38 0 0 0 Tarantaran 9 Tarantaran 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10 Chabhal 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 Bhikhiwind 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12 Khemkaran 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 13 Patti 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Nau. Panuan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 15 Khadur Sahib 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 16 Harike 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 TOTAL 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GURDASPUR 17 Dina Nagar 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 18 Gurdaspur 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 19 Dhariwal 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 20 Kalanaur 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 21 Kahnuwan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 22 Batala 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 23 Quadian 0 0 750 750 615 1074 450 24 S. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE for AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi

AIR POWER Journal of Air Power and Space Studies Vol. 3, No. 3, Monsoon 2008 (July-September) AIR POWER CENTRE FOR AIR POWER STUDIES New Delhi AIR POWER is published quarterly by the Centre for Air Power Studies, New Delhi, established under an independent trust titled Forum for National Security Studies registered in 2002 in New Delhi. Board of Trustees Shri M.K. Rasgotra, former Foreign Secretary and former High Commissioner to the UK Chairman Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff and former Governor Maharashtra and Rajasthan Smt. H.K. Pannu, IDAS, FA (DS), Ministry of Defence (Finance) Shri K. Subrahmanyam, former Secretary Defence Production and former Director IDSA Dr. Sanjaya Baru, Media Advisor to the Prime Minister (former Chief Editor Financial Express) Captain Ajay Singh, Jet Airways, former Deputy Director Air Defence, Air HQ Air Commodore Jasjit Singh, former Director IDSA Managing Trustee AIR POWER Journal welcomes research articles on defence, military affairs and strategy (especially air power and space issues) of contemporary and historical interest. Articles in the Journal reflect the views and conclusions of the authors and not necessarily the opinions or policy of the Centre or any other institution. Editor-in-Chief Air Commodore Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (Retd) Managing Editor Group Captain D.C. Bakshi VSM (Retd) Publications Advisor Anoop Kamath Distributor KW Publishers Pvt. Ltd. All correspondence may be addressed to Managing Editor AIR POWER P-284, Arjan Path, Subroto Park, New Delhi 110 010 Telephone: (91.11) 25699131-32 Fax: (91.11) 25682533 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.aerospaceindia.org © Centre for Air Power Studies All rights reserved. -

Armed Forces Tribunal , Kolkata Bench Application No

FROM NO. 21 (SEE RULE 102(1)) ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL , KOLKATA BENCH APPLICATION NO : O.A NO. 117 OF 2012 ON THIS 10th DAY OF APRIL, 2013 CORAM HON’BLE JUSTICE RAGHUNATH RAY , MEMBER (JUDICIAL ) HON’BLE LT GEN KPD SAMANTA, MEMBER (ADMINISTRATIVE) Hav Bal Bahadur Katuwal, Son of Sri Gyan Bahadur Katuwal , Village Upper Dilaram, Chaukidada, P.O. Bagora, Pin – 734 224, District Darjeeling, West Bengal. ……………Appellant -VS- 1. Union of India through The Secretary, Ministry of Defence, South Block, New Delhi. 2. The Chief of Army Staff, Integrated HQ of MoD (Army), DHQ PO, New Delhi. 3. The Chief Records Officers, 39, Gorkha Training Centre, Varanasi Cantonment, Uttar Pradesh, PIN – 221002. 4. The Officer Commanding, 3/9 GR (Chindits), C/O 56 APO, PIN 910 253. ………………. Respondents 2 For the petitioner: Mrs. Maitrayee Trivedi Dasgupta, Advocate For the respondents: Mr. Souvik Nandy, Advocate JUDGEMENT AND ORDER Per HON’BLE LT GEN KPD SAMANTA, MEMBER (ADMINISTRATIVE) This matter relates non-grant of promotion to the rank of Naib Sudedar despite the applicant being eligible for such promotion. The applicant is an ex-Havildar of 3/9 GR (Gorkha Rifles) who had retired in the rank of Havildar though, as submitted by him, he could have been promoted to the next rank i.e. of Naib Subedar that would have automatically enhanced service span as per the stipulated terms and conditions of service. Being aggrieved, he has approached this Tribunal through this Original Application seeking the intervention of this AFT to enable his promotion to the rank of Naib Subedar.