Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Administrative Service Officers, with Immediate Effect, in the Public Interest

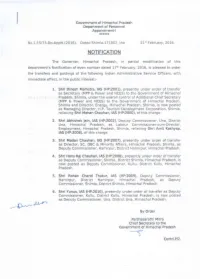

I Government of Himachal Pradesh Department of Personnel Appointment-I ****** No .1-15!73-Dp-Apptt.{2016}, Dated Shimla-171002, the 2pt February, 2016. NOTIFICATION The Governor, Himachal Pradesh, in partial modification of this department's Notification of even number dated 17th February, 2016, is pleased to order the transfers and postings of the following Indian Administrative Service Officers, with immediate effect, in the public interest:- 1. Shri Dinesh Malhotra, lAS (HP:2001), presently under order of transfer as Secretary (MPP & Power and NCES) to the Government of Himachal i - .. ,/ J-i Pradesh, Shimla, under the overall control of Additional Chief Secretary (MPP & Power and NCES) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla and Director, Energy, Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, is now posted as Managing Director, H.P. Tourism Development Corporation, Shimla, relieving Shri Mohan Chauhan, lAS (HP:2000), of this charge. 2. Shri Abhishek Jain, lAS (HP:2002), Deputy Commissioner, Una, District Una, Himachal Pradesh, as Labour Commissioner-cum-Director, Employment, Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, relieving Shri Amit Kashyap, lAS (HP:2008), of this charge. 3. Shri Madan Chauhan, lAS (HP:2007), presently under order of transfer as Director, SC, OBC & Minority Affairs, Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, as Deputy Commissioner, Hamirpur, District Hamirpur, Himachal Pradesh. 4. Shri Hans Raj Chauhan, lAS (HP:2008), presently under order of transfer as Deputy Commissioner, Shimla, District Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, is now posted as Deputy Commissioner, Kullu, District Kullu, Himachal Pradesh. 5. Shri Rohan Chand Thakur, lAS (HP:2009), Deputy Commissioner, Hamirpur, District Hamirpur, Himachal Pradesh, as Deputy Commissioner, Shimla, District Shim!a, Himachal Pradesh. 6. -

Border Trade: Reopening the Tibet Border Claude Arpi the First Part of This Paper Concluded with This Question: Can the Borders

Border Trade: Reopening the Tibet Border Claude Arpi The first part of this paper concluded with this question: can the borders be softened again? Can the age-old relation between the Tibetans and the Himalayans be revived? The process has started, though it is slow. This paper will look at the gains acquired from the reopening of the three land ports, but also at the difficulties to return to the booming trade which existed between Tibet and India before the invasion of Tibet in 1950 and to a certain extent till the Indo-China war of 1962. It will also examine the possibility to reopen more land ports in the future, mainly in Ladakh (Demchok) and Arunachal Pradesh. Tibet’s Economic Figures for 2012 According to a Chinese official website, the Tibetan Autonomous Region is economically doing extremely well. Here are some ‘official’ figures: • Tibet's GDP reached 11.3 billion US $ in 2012, an increase of 12 % compared to the previous year (Tibet's GDP was 9.75 billion US $ in 2011 and 8.75 billion US $ in 2010). • Tibet's economy has maintained double-digit growth for 20 consecutive years. • Fixed asset investment have increased by 20.1 % • The tax revenues reached 2.26 billion US $ (fiscal revenue grew by 46%) • And Tibet received over 11 million domestic and foreign tourists earning 2.13 billion US $ Tibet’s Foreign Trade Figures for 2012 The foreign trade is doing particularly well. On January 23, 2013, Xinhua announced that Tibet has registered new records in foreign trade. A Chinese government agency reported that the foreign trade of the Tibetan Autonomous Region reached more than 3 billion U.S. -

Socio Economic Vulnerability of Himachal Pradesh to Climate Change

Final Technical Report (FTR) Project Type-CCP-DST Socio Economic Vulnerability of Himachal Pradesh to Climate Change Financial Support provided by Department of Science and Technology, Government of India Integrated Research and Action for Development (IRADe) C-80, Shivalik, Malviya Nagar, New Delhi-110017 Tel + 91 11 2668 2226/ Fax +91 11 2668 2226 www.irade.org Final Technical Report (FTR) Project Type-CCP-DST Socio Economic Vulnerability of Himachal Pradesh to Climate Change Submitted to Climate Change program, Department of Science and Technology (CCP- DST), Government of India Project Team Dr. Jyoti Parikh Dr. Ashutosh Sharma Chandrashekhar Singh Asha Kaushik Mani Dhingra ii Acknowledgments We thank everyone who contributed to the richness and the multidisciplinary perspective of this report “Socio Economic Vulnerability of Himachal Pradesh to Climate Change ’’. We are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India for choosing IRADe to do this study. We are grateful to Dr Akhilesh Gupta, Scientist-G & Head, Strategic Programmes, Large Initiatives and Coordinated Action Enabler (SPLICE) and Climate Change Programme (CCP), DST, Dr. Nisha Mendiratta, Director / Scientist 'F' SPLICE & CCP Division, DST, Dr Rambir Singh, Scientist-G, SPLICE, DST and Dr. Anand Kamavisdar, Scientist – D, DST for extending their support during the execution of this project. We are also thankful to the expert committee on Climate Change Programme (CCP) of DST for reviewing the project report during the course of this study. The study could not have been taken place without the support of Dr. Pankaj Sharma Joint, Director, Directorate of Economics and Statistics, H.P, Mr. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

A Polyandrous Society in Transition: a CASE STUDY of JAUNSAR-BAWAR

10/31/2014 A Polyandrous Society in transition: A CASE STUDY OF JAUNSAR-BAWAR SUBMITTED BY: Nargis Jahan IndraniTalukdar ShrutiChoudhary (Department of Sociology) (Delhi School of Economics) Abstract Man being a social animal cannot survive alone and has therefore been livingin groups or communities called families for ages. How these ‘families’ come about through the institution of marriage or any other way is rather an elaborate and an arduous notion. India along with its diverse people and societies offers innumerable ways by which people unite to come together as a family. Polyandry is one such way that has been prevalent in various regions of the sub-continent evidently among the Paharis of Himachal Pradesh, the Todas of Nilgiris, Nairs of Travancore and the Ezhavas of Malabar. While polyandrous unions have disappeared from the traditions of many of the groups and tribes, it is still practiced by some Jaunsaris—an ethnic group living in the lower Himalayan range—especially in the JaunsarBawar region of Uttarakhand.The concept of polyandry is so vast and mystifying that people who have just heard of the practice or the people who even did an in- depth study of it are confused in certain matters regarding it. This thesis aims at providing answers to many questions arising in the minds of people who have little or no knowledge of this subject. In this paper we have tried to find out why people follow this tradition and whether or not it has undergone transition. Also its various characteristics along with its socio-economic issues like the state and position of women in such a society and how the economic balance in a polyandrous family is maintained has been looked into. -

SEEK a SNOW LEOPARD; SPITI, HIMACHAL PRADESH Feb 9- 21, 2014 12 Nights 13 Days

SEEK A SNOW LEOPARD; SPITI, HIMACHAL PRADESH Feb 9- 21, 2014 12 nights 13 days Photo from thewildlifeofindia.com Known throughout the world for its beautiful fur and shy, elusive behavior, the endangered snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is found in the rugged mountains of Central Asia. Snow leopards are perfectly adapted to the cold, barren landscape of their high-altitude home, but human threats have created an uncertain future for the cats. Despite a range of over 2 million km2, there are only between 4,000 and 6,500 snow leopards left in the wild. On this trip we search for a snow leopard in the highlands of Spiti valley. Rudyard Kipling describes Spiti in "Kim" in these words: "At last they entered a world within a world - a valley of leagues where the high hills were fashioned of the mere rubble and refuse from off the knees of the mountains... Surely the Gods live here. The valleys of Kullu and Lahaul bound Spiti, locally pronounced “Piti”, on its south and west; the region of Ladakh lies to the north and the Kalpa valley lies to the southeast. Geologically and archaeologically, Spiti is a living museum. The mountains are devoid of any vegetation and erosion by wind, sun and snow over thousands of years has laid bare the rocks. The rugged and rocky mountain slopes sweep down to the riverbeds giving the landscape a moon-like appearance. From Chandigarh, we go via Shimla and Rampur to Kaza- headquarters of Spiti. From here we head out to Kibber, and then into the back-of-the beyond wilder parts of the Spitian Himalayas where we track Snow Leopards. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Hjar 41 (1) 2015

HIMACHAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH Vol. 41 (1), June 2015 DIRECTORATE OF RESEARCH CSK HIMACHAL PRADESH KRISHI VISHVAVIDYALAYA PALAMPUR-176 062, INDIA Regd. No. 8270-74 dated 13.12.1973 HIMACHAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH Vol. 41 No. 1 June 2015 Page No. Contents Vegetable grafting: a boon to vegetable growers to combat biotic and abiotic stresses 1-5 Pardeep Kumar, Shivani Rana, Parveen Sharma and Viplove Negi Impact of rainfall on area and production of rabi oilseed crops in Himachal Pradesh 6-12 Rajendra Prasad and Vedna Kumari Impact of National Agricultural Innovation Project on socio-economic analysis of pashmina goat 13-19 keepers in Himachal Pradesh M.S. Pathania Production potential of rice-based cropping sequences on farmers’ fields in low hills of Kangra 20-24 district of Himachal Pradesh S.K. Sharma, S.S. Rana, S. K. Subehia and S.C. Negi Economics of post-emergence weed control in garden pea ( Pisum sativum L.) under mid hill 25-29 condition of Himachal Pradesh Anil Kumar Mawalia, Suresh Kumar and S.S. Rana Studies on the preparation and evaluation of value added products from giloy ( Tinospora cordi- 30-35 folia ) Sangeeta Sood and Shilpa Factors affecting socio-economic status of farm workers of tea industry in Himachal Pradesh 36-41 Parmod Verma and Sonika Gupta Assessment of yield and nutrient losses due to weeds in maize based cropping systems 42-48 Suresha, Ashish Kumar, S.S. Rana, S.C. Negi and Suresh Kumar Analysis of yield gaps in black gram ( Vigna mungo ) in district Bilaspur of Himachal Pradesh 49-54 Subhash Kumar, A.K. -

2017-18 Page 1 and Are Protected by Fairly Extensive Cover of Natural Vegetation

For Official Use Only GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK HIMACHAL PRADESH (2017-2018) NORTHERN HIMALAYAN REGION DHARAMSHALA (H.P) March, 2019 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK HIMACHAL PRADESH (2017-2018) By Rachna Bhatti Vidya Bhooshan Scientist ‘C’ Senior Technical Assistant (Hydrogeology) NORTHERN HIMALAYAN REGION DHARAMSHALA (H.P) March, 2019 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK HIMACHAL PRADESH 2017-2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Central Ground Water Board, NHR has set up a network of 128 National Hydrograph Stations in the state of Himachal Pradesh. The monitoring commenced in the year 1969 with the establishment of 3 observation wells and since, then the number of monitoring station are being increased regularly so as to get the overall picture of ground water scenario in different hydrogeological set up of the state. Most of the area in Himachal Pradesh is hilly enclosing few small intermontane valleys. The traditional ground water structures under observation at present are dugwells and are mostly located in the valley areas only. Therefore, the ground water regime monitoring programme is concentrated mainly in valley areas of the state and some places in hard rock areas. All the 128 National Hydrograph Stations are located only in 7 districts out of the 12 districts in Himachal Pradesh. The reason being hilly terrain, hard approachability and insignificant number of structures available for monitoring. The average annual rainfall in the state varies from 600 mm to more than 2400 mm. The rainfall increases from south to north. -

High Altitude Survival

High altitude survival Conflicts between pastoralism andwildlif e in the Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0873 6775 Promotor Prof.Dr .H .H .T .Prin s Hoogleraar inhe tNatuurbehee r ind eTrope n enEcologi eva n Vertebraten Co-promotor : Dr.S .E .Va nWiere n Universitair Docent, Leerstoelgroep Natuurbeheer in de Tropen enEcologi eva nVertebrate n Promotie Prof.Dr .Ir .A .J .Va n DerZijp p commissie Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr .J .H . Koeman Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr . J.P .Bakke r Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof.Dr .A .K .Skidmor e International Institute forAerospac e Survey and Earth Sciences, Enschede High altitude survival: conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife inth e Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra Proefschrift ter verkrijging van degraa d van doctor opgeza g van derecto r magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit prof. dr. ir. L. Speelman, inhe t openbaar te verdedigen opvrijda g 14decembe r200 1 des namiddags te 13:30uu r in deAul a -\ •> Mishra, C. High altitude survival:conflict s between pastoralism andwildlif e inth e Trans-Himalaya Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis (2001); ISBN 90-5808-542-2 A^ofZC , "SMO Propositions 1. Classical nature conservation measures will not suffice, because the new and additional measures that have to be taken must be especially designed for those areas where people live and use resources (Herbert Prins, The Malawi principles: clarification of thoughts that underlaythe ecosystem approach). 2. The ability tomak e informed decisions on conservation policy remains handicapped due to poor understanding of the way people use natural resources, and the impacts of such resource use onwildlif e (This thesis). -

Environment Assessment and Management Framework

- Draft - Himachal Pradesh Forests for Prosperity Project Environment Assessment & Management Framework Submitted By Himachal Pradesh Forests Department, Government of Himachal Pradesh, India Prepared By G. B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment & Sustainable Development, Himachal Regional Centre, Mohal - Kullu - 175 126, Himachal Pradesh SEPTEMBER , 2018 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 2 List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables: ...................................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 Introduction to the Proposed Project ................................................................................. 16 1.1 Background to the HP FPP project .............................................................................................. 16 1.2 Project development objective (PDO) ........................................................................................ 19 1.3 Project Beneficiaries ................................................................................................................... 19 1.4 Detailed Description of -

Eco –Tourism and Its Development in Tribal Regions of Himachal Pradesh Mr

IJA MH International Journal on Arts, Management and Humanities 3(1): 24-29(2014) ISSN No. (Online): 2319 – 5231 Eco –Tourism and its Development in Tribal Regions of Himachal Pradesh Mr. Pankaj Sharma and Mr. Ravi Parkash Department of Hotel and Tourism Management, Manav Bharti University, Solan , Himachal Pradesh (Corresponding author Pankaj Sharma) (Received 05 December, 2013 Accepted 20 February, 2014) ABSTRACT: The tribal areas of Himachal Pradesh are known for natural beauty. Eco tourists are often motivated by the chance to experience tribal culture, which can have a positive and affirming effect on that culture. Schemes like Home Stay started by Dept. of Tourism & Civil Aviation, Himachal Pradesh on the one hand saves the tribal areas from becoming concrete jungles and on the other gives a firsthand experience of tribal culture to the tourists. Moreover this also becomes a means of income generating activity for tribals. The tribal areas of Himachal such as Spiti, Kinnaur, Sangla, kalpa and Bharmour are all major tourist destinations today. The tribal population in Himachal Pradesh is about 11% of the total population i.e. 244587 lakh. These tribal include the Kinners or Kinnaure, the Lahules, the Spitians, the Pangwalas, the Gaddis and the Gujjars. However it is often said, tourism destroys tourism. It seems to be true in the case of the Sangla valley in Kinnaur, which is fast losing its scenic charm and tranquillity due to the unregulated growth of the tourism industry. New buildings are coming up in a haphazard way, as there is no plan for the development of the tourist destination.