Figuring Colonialism - Reflections on Banana's Social Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Pipes Adsorba Pipes Alba Pipes

Prices correct at time of printing 26/09/2018 SPECIAL OFFERS - Pipes Black Swan 46 Rattrays Pipe £109.99 Chacom Robusto Brown Sandblast 190 Pipe (CH009) £85.99 Davidoff 9mm Discovery Malawi Pipe (DAV03) £269.00 Hardcastle Argyle 101 Fishtail Pipe (H0049) £34.99 Hardcastle Briar Root 103 Checkerboard Fishtail Straight Pipe (H0025) £41.49 Hardcastle Camden 102 Smooth Fishtail Pipe (H0046) £52.99 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Apple Bent Pipe (LZ10) £220.00 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Unique Semi Bent Pipe (LZ08) £220.00 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1055) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 Fishtail Pipe (G1065) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 069 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1052) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 408 Fishtail Pipe (G1066) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1051) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 Fishtail Pipe (G1067) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent XL90 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1059) £69.99 Peterson Aran Smooth Pipe - 003 (G1034) £61.99 Peterson Around the World USA X105 Silver Mounted Pipe £79.99 Peterson Donegal Rocky Pipe - 003 (G1172) £65.99 Peterson Kinsale Curved Pipe XL15 (Squire) £83.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 120 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 305 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 338 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 408 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - B10 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 106 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 606 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - X220 £78.99 Peterson Liscannor Bent Pipe - X220 £43.99 Peterson Standard System Rustic 313 Pipe (SR005) £72.99 Peterson Standard System Smooth 302 Pipe (G1255) £72.99 Rattrays Limited Edition Turmeaus 1817 Green Pipe No. -

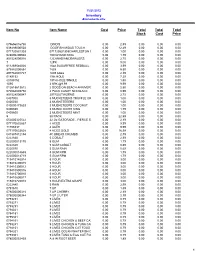

NH Convenient Database

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

Download the Forecast Channel for the Wii and Keep the System Online, the Weather During the Game Will Reflect That of the Weather in Your Town Or City (Ex

Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None Unlockables Alternative Endings Depending on whether you save certain people during the course of the game, you'll receive one of 4 different endings. Unlockable How to Unlock Best Ending (Narracott, Get to Lombard before he dies, then attack Lombard and Claythorne murderer to save Claythorne. survive) Poor Ending (Narracott and Reach Lombard before he dies, and do not attack Lombard survive) the murderer. Reasonable Ending (Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, then attack and Claythorne survive) murderer to save Claythorne. Worst Ending (Only Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, and do not survives) attack the murderer. Alien Syndrome Unlockables Unlock Extra Difficulties In order to unlock the other two game difficulties, Hard and Expert, you must beat the game on the previous difficulty. Unlockable How to Unlock Unlock Expert Difficulty Beat the game on Hard Difficulty. Unlock Hard Difficulty Beat the game on Normal Difficulty. Animal Crossing: City Folk Unlockables Bank unlockables Deposit a certain amount of bells into bank. Unlockable How to Unlock Box of Tissues Deposit 100,000 bells into the bank. Gold Card Reach "VIP" status. Shopping Card Deposit 10,000 bells into the bank. Piggy Bank Deposit 10,000,000 Bells ------------------------------- Birthday cake Unlockable How to Unlock Birthday Cake Talk to your neighbors on your birthday ------------------------------- Harvest Set To get a furniture item from the Harvest Set, You must talk to Tortimer after 3pm on Harvest Day. He will give you a Fork and Knife pair, telling you that the 'Special Guest' hasn't shown up yet. -

JUNE 30, 1900. ICT&Jvsbsi CENTS

DS PORTLAND PRESS. S PRICK THREE ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. 39. PORTLAND, MAINE, SATURDAY MORNING, JUNE 30, 1900._ICT&jVSBSI CENTS. down the steep Incline of Mission hill un- KJCW ADVIHTlIMBm PRESIDENT OPTIMISTIC. der perfect control, as several pn*«-nger> Tklaki Ik. Tro.kl. la Cklu la All were taken on a short distance from the top. Probably by the breaking of a link "Q of the chain which engage* the winding Washington, Jane The President and controls the the car for bla Canton ASHORE. post brakes, le OREGON FROM SEYMOUR. quitting Washington gained headway rapidly and In a moment BIG CRT home full of oonndenoe that the tonight, It was moving at a frightful rate toward situation In China has improved though the vladuat under the railroad bridge. It it le fair to say that all the members of passed this In safety but at a turn In the his ofllolal family do not agree with him track the car left the rattled across in that oonoluskra. Indead the day's rails, III PRICES. the pavements, mounted tho ourbstoi • news limited though It was to a single and striking the market ploughed away Extraordinary trade* are cablegram from Admiral Kerapff and the 800 feet of the When the of lnetruotlons to Ueneral square bnlldlng. offered for One Week preparation America’s Most Famous Only. British Admiral Tells of Adven- oar stopped It was completely burled n set calculated to Battleship Story Chaffee, out nothing Russet button the market and tho motorman was vainly Children’* goat, strengthen the hope* of the friends of the tugging at the brake. -

View / Open Huang Oregon 0171A 12343.Pdf

“YES! WE HAVE NO BANANAS”: CULTURAL IMAGININGS OF THE BANANA IN AMERICA, 1880-1945 by YI-LUN HUANG A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Yi-lun Huang Title: “Yes! We Have No Bananas”: Cultural Imaginings of the Banana in America, 1880-1945 This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the English Department by: Mary Wood Chairperson Mark Whalan Core Member Courtney Thorsson Core Member Pricilla Ovalle Core Member Helen Southworth Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2018 ii © 2018 Yi-lun Huang iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Yi-lun Huang Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2018 Title: “Yes! We Have No Bananas”: Cultural Imaginings of the Banana in America, 1880-1945 My dissertation project explores the ways in which the banana exposes Americans’ interconnected imaginings of exotic food, gender, and race. Since the late nineteenth century, The United Fruit Company’s continuous supply of bananas to US retail markets has veiled the fruit’s production history, and the company’s marketing strategies and campaigns have turned the banana into an American staple food. By the time Josephine Baker and Carmen Miranda were using the banana as part of their stage and screen costumes between the 1920s and the 1940s, this imported fruit had come to represent foreignness, tropicality, and exoticism. -

224 Nave- Were Confined for Disciplinary Pur- County-Wide Tuberculosis Commlbg Has Been Put Tl Years, the Celebrant and Her !Wall Street'

Joins Sales.Staff Monmouth To House, Wghlands^Woman 101 Of Red Bank Firm Attractive Places Sold 200 German PW's Xmas Seal Sale Edward R. O'Kane of 61 Hub- A group of approximately 200 On Thanksgiving Day bard avenue,. River Plaza, has Join- German prisoners of war. is sched- By Ray H. Stillman uled to arrive at. Fort Monmouth Thanksgiving Day ed the sales staff of the Walker early next week, according to Brig, and Tindall real estate and insur- Gen, Stephen H.Sheirill, command- ance firm, 7 Mechanic street, Red ing general of the Eastern Signal MM. Lavinia Minton's Birthday To Be Bank. ..'-..; One In Highlands, Another Corps Training Center, Proceeds U»ed In Fight . Mr. O'Kane haa been a resident Half of the contingent will be as- of River Plaza fly* year*,' moving In The Holihdel District signed to the separation center, Celebrated With "Open Hoii»e" to this address from Purity Station, and the remainder Is to be placed Against Tuberculosis ,."" N*w Tork. - He has been employed on duty In post overhead activities. Thanksgiving Is tb&AOlst birth- by the government at Raritan ars- Ray H. SttUtaan 4 AwocUtesAf The prisoners will be quartered The annual Monmouth Count] da/ of MM. Lavinla. Mount Min- enal Before bis .employment by Eatontown report "the sale of the in the stockade area formerly oc- Christmas seal campaign op New Ppntiac too, a native of Red Bask frfd a the government he was a salesman Shrewsbury Club attractive home of Cr. and Mrs, cupied by American soldiers' who Free Library ^ Thanksgivirig day, sponsored by th»| resident Of Highland! for the last of over-the-counter securities in Henry A. -

St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924

University of Central Florida STARS St. Cloud Tribune Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-2-1924 St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924 St. Cloud Tribune Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Cloud Tribune by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation St. Cloud Tribune, "St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924" (1924). St. Cloud Tribune. 108. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune/108 1S24 OCTOBER 1924 [SlWl^NtTtJEl-'^^ (SAT ST ll ,11 il TKMTrJL\TI!f A.lv .''...a \V ...... and Watch Heaulli w Wednesday ,i,i.n,.H* I . *-<> HI 1J2J3J4 Tuesday, Beptoa***er SO HO tt o • o s /j 6 j y iu ii M.in.I,iv. Si'lH.'iHl.il- L'II T8 711 Ruaday, iepmubae H aa-M 12 12 13114115116 17118 .Nallli'diiy. S,.|lli'llll.iH- L'T BS T2 Friday, Si'lHl'llilllH- L'II . Sl "1 Vi) Zu Z122 23|24j[25 ^©^jILa^ Thursday, September 28 MI T'J 26i 27i|28|29 30ii31|| ^^^ ^^ TM* Wll.. NO. «—KKJIIT PAGES THIS WEKK. ST. CM) I'll OWKOIaA COINTV, FLORIDA, Till KNI>AV, ,l( Illlll It >, l»2l FIVK CCNTfl TIIK COPY—S3.00 A VKAR ++.:.^..;..:..*.+.j..;..:.+.H.+.:. - • r*-r | •*t-++**H-+*+*+*>+++++-*+++++++•*> + MUCH GOOD WORK DONE SEMINOLE HOTEL RE-OPENED FOR -*-*-»cnr.i BAWD CONCERT kri-wa,, • " TIIK .** 'IIOOI.MASTKK'S * ULnwu,, HAM) OONCKRT FK1IIA1 -:* I'KAVKK * AT City l'urk e} AT NEW SCHOOL UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT LAST SUNDAY NOON THURSDAY WELL *9> + 8 If. -

What Is the Best Way to Begin Learning About Fashion, Trends, and Fashion Designers?

★ What is the best way to begin learning about fashion, trends, and fashion designers? Edit I know a bit, but not much. What are some ways to educate myself when it comes to fashion? Edit Comment • Share (1) • Options Follow Question Promote Question Related Questions • Fashion and Style : Apart from attending formal classes, what are some of the ways for someone interested in fashion designing to learn it as ... (continue) • Fashion and Style : How did the fashion trend of wearing white shoes/sneakers begin? • What's the best way of learning about the business behind the fashion industry? • Fashion and Style : What are the best ways for a new fashion designer to attract customers? • What are good ways to learn more about the fashion industry? More Related Questions Share Question Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Question Stats • Latest activity 11 Mar • This question has 1 monitor with 351833 topic followers. 4627 people have viewed this question. • 39 people are following this question. • 11 Answers Ask to Answer Yolanda Paez Charneco Add Bio • Make Anonymous Add your answer, or answer later. Kathryn Finney, "Oprah of the Internet" . One of the ... (more) 4 votes by Francisco Ceruti, Marie Stein, Unsah Malik, and Natasha Kazachenko Actually celebrities are usually the sign that a trend is nearing it's end and by the time most trends hit magazine like Vogue, they're on the way out. The best way to discover and follow fashion trends is to do one of three things: 1. Order a Subscription to Women's Wear Daily. This is the industry trade paper and has a lot of details on what's happen in fashion from both a trend and business level. -

Special Publications the Museum Texas Tech University

HARVARD UNIVERSITY Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology I I SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS THE MUSEUM TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Bats of Egypt Mazin B. Qumsiyeh } / DtU ! I ibd5 Hm v jAO UNIVERSITY No. 23 December 1985 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Lauro F. Cavazos, President Regents.-—John E. Birdwell (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jerry Ford, Rex Fuller, Larry D. Johnson, W. Gordon McGee, Wesley W. Masters, Wendell Mayes, Jr., and Ann Sowell. Donald R. Haragan, Vice President for Academic Affairs and Research Editorial Committee.—Clyde Hendrick (Chairman), Dilford C. Carter, E. Dale Cluff, Monty E. Davenport, Donald R. Haragan, Clyde Jones, Stephen R. Jorgensen, Richard P. McGlynn, Janet Diaz Perez, Marilyn E. Phelan, Rodney L. Preston, Charles W. Sargent, Grant T. Savage, Jeffrey R. Smitten, Idris R. Traylor, Jr., and David A. Welton. The Museum Special Publications No. 23 102 pp. 6 December 1985 Paper, $18.00 Cloth, $40.00 Special Publications of The Museum are numbered serially, paged separately, and published on an irregular basis under the auspices of the Vice President for Academic Affairs and Research and in cooperation with the International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies. Copies may be purchased from Texas Tech Press, Sales Office, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, U.S.A. Institutions interested in exchanging publications should address the Exchange Librarian at Texas Tech University. ISSN 0149-1768 ISBN 0-89672-137-X (paper) ISBN 0-89672-138-8 (cloth) Texas Tech Press, Lubbock, Texas 1985 SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS THE MUSEUM TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Bats of Egypt Mazin B. Qumsiyeh No. 23 December 1985 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Lauro F. -

The Republican Journal; Vol. 94. No. 46

The Republican Journal. XO. 4(1. **> BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, NOVEMHEIi 1(5, 1022. FIVE CENTS v7h4MH})4.--------.-----— is a Activities typical American of the true blue Burnham Has Fire. MISS FANNIE I. HOPKINS. II !L CHURCHES An Armlstice Da;- type. $12,000 PERSONAL Old-Time Revival A Capt Harry Foster of Company K of Miss Fannie I. of of Haaelline Post, Fire Tuesday morning, Nov. 7, com- The funeral Hopkins First Universaust Church. Ser- ih* A i»r«*> of the Third Maine brought the greeting* Mr*. W. L. Hall went to Auburn Wed- A genuine old fashioned revivsl of re- *“* pletely destroyed the two story building Newton, Mass., formerly of Belfast, took vices will be held next Sunday morning i ,t|e Brs'cy. Commander of the 260,000 citizen soldiers of our nesday a abort visit with relatives. ligious interest is being developed in the j owned and occupied Frank B. Brown at 10.4-5 a. m. Sermon the country who tiave pledged themselves to place at the chapel in Grove cemetery at by pastor, meetings being held in the Methodist of * rnnstire as a garage with living apartment on the Rev. W illiam and music by the Mr. and Mrs. Charles E. Nash have re- annual events uphold the principles and carry on the I o’clock Sunday with a large attendance Vaughan, church, under the direction of Miss The fourth second floor and the Free Baptist church choir. school follows the morn- turned from a visit with relatives in Al- of Frank Durham struggles of the men of the World War. -

AYALA-WALSH.Thesis.Oct. 24

LIBERATING MACHISMO: DECONSTRUCTING THE STEREOTYPES OF LATINIDAD IN ALBERTO KORDA’S GUERRILLERO HEROICO by Johanna Ayala-Walsh A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 © Copyright Johanna Ayala-Walsh 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the professors in the English Department at Florida Atlantic University. You have inspired my writing and research for the past five years, guiding and encouraging me towards the finish line. This work is the culmination of your efforts as teachers. Thanks again for everything. iv ABSTRACT Author: Johanna Ayala-Walsh Title: Liberating Machismo: Deconstructing the Stereotypes of Latinidad in Alberto Korda’s Guerrillero Heroico Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Raphael Dalleo Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2012 This thesis examines the Alberto Korda Guerrillero Heroico image within the realm of U.S. Latino/a fiction. Drawing from several trends that constitute Latino/a identity as either resistant to white mainstream hegemonies, or as a performative construct, I argue that a collective Hispanic identity is found somewhere between these two extremes. Corporate discourses have perpetuated stereotypes of Latino masculinity to limit any alternate and nuanced portrayal of Latinidad. Specifically, I posit that the corporate use of the Che photograph illustrates Latin men as hypermasculine, limiting Latin-ness to a performance of its mainstream depiction. To combat the commercialization of the print, the novel Loving Che imagines new possibilities for the Hispanic community and its relationship to the U.S.