And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Diversifying the Art Tech World

Media-N | The Journal of the New Media Caucus Summer + 2018: Volume 14, Issue 1, Pages 56–76 ISSN: 1942-017X Media-N | Diversifying the Art Tech World JOELLE DIETRICK Assistant Professor of Art and Digital Studies, Davidson College KATHY RAE HUFFMAN Independent Curator ABSTRACT In this transcript of a panel discussion at the 2018 College Art Association conference, participants discuss the gender gap in the art tech world. Against a backdrop of both the current political climate and recent reporting into the gender gap in the tech industry, panelists gave short presentations of their work with commentary on their early access to technology, mentors and other support structures that helped them to create significant artwork. Questions focused on how, going forward, we can support younger, female and trans new media artists, particularly artists of color. Joelle Dietrick [JD]: This panel started with the gender gap, but in light of the recent election, clearly needed to be expanded to consider other forms of identity, to include race and class. This group of panelists bravely offer brief descriptions of how they learned to be confident and productive in fields that were typically dominated by white cis males. Recognizing that the audience knows as much as we do, all have kept their presentations incredibly brief – about ten minutes each – to allow time for discussion. On the topic of diversity, it’s extremely important to me that we consider both visible and invisible forms of diversity. Coming from a working-class family, I did not have the economic or social capital that makes success in this field more likely. -

Desire and Homosexuality in the '90S Latino Theatre Maria Teresa

SPRING 1999 87 Out of the Fringe: Desire and Homosexuality in the '90s Latino Theatre Maria Teresa Marrero The title of this essay refers to a collection of theatre and performance pieces written and performed between 1995 and 1998 by some of the most prolific Latino artists working in the late 20th century.l One the characteristics that marks them is the lack of overall homogeneity found among the pieces. Some, like Svich's Alchemy of Desire/Dead-Man's Blues (1997) and Fur (1995) by Migdalia Cruz, function within an internal terrain that the play itself constructs, making no allusions to identifiable, specific, geographic locations (be they Hispanic or Anglo). Theirs is a self-contained world set within what could be termed the deliberations of language, the psychological and the theatrical. Others, like Alfaro's Cuerpo politizado, (1997), Greetings from a Queer Señorita (1995) by Monica Palacios, Trash (1995) by Pedro Monge-Rafuls, Stuff! (1997) by Nao Bustamante and Coco Fusco, and Mexican Medea (1997) by Cherríe Moraga, clearly take a stance at the junction between the sexual, sexual preference, AIDS, postcolonial discourse and identity politics. While the collection of plays and performances also includes fine work by Oliver Mayer, Nilo Cruz and Naomi Iizuka, for the purpose of this essay I shall concentrate on the above mentioned pieces. The heterogeneous and transitory space of these texts is marked by a number of characteristics, the most prominent and innovative of which is the foregrounding of sexual identities that defy both Latino and Anglo cultural stereotypes. By contemplating the central role of the physical body and its multiplicity of desires/states, I posit this conjunction as the temporary space for the performance of theatrical, cultural, and gender expressions. -

Rafa Esparza Carmen Argote, Nao Bustamante, Beatriz Cortez, Timo

tierra. sangre. oro. Rafa Esparza WITH Carmen Argote, Nao Bustamante, Beatriz Cortez, Timo Fahler, Eamon Ore-Giron, Star Montana AND Sandro Cánovas, Maria Garcia, Ruben Rodriguez AUGUST 25, 2017 – MARCH 18, 2018 1 Tierra. Sangre. Oro. is a group exhibition envisioned by Rafa Esparza that includes new work by Carmen Argote, Beatriz Cortez, Esparza, Timo Fahler, Eamon Ore-Giron; new and existing photographs by Star Montana; a major body of work by Nao Bustamante; the contributions of adoberos/artists Sandro Cánovas, Maria Garcia, Ruben Rodriguez, as well as many hands from the community of Marfa. Rafa and I began a conversation in June 2016. I had followed his work closely before we met, and had seen two of his adobe inter- ventions next to the Los Angeles River, building: a simulacrum of power (2014) and Con/Safos (2015). The generous and generative nature of his practice was immediately apparent to me, each architecture offering itself up both as a surface for other artists and as a physical embodiment of labor and land. Those two projects convinced me that Rafa should come to Marfa to see the vernacular adobe architecture of the region, and many months later we started dreaming, together, about a project for Ballroom. It has been a great privilege to work with Rafa and all of the artists that manifested this exhibition. In Marfa, Rafa worked along- side Sandro Cánovas, Maria Garcia, and Ruben Rodriguez for over two months, mixing adobe and molding bricks, to produce tons of building material that he used to create a rich ground for his peers and Ballroom’s visitors. -

Pipes Adsorba Pipes Alba Pipes

Prices correct at time of printing 26/09/2018 SPECIAL OFFERS - Pipes Black Swan 46 Rattrays Pipe £109.99 Chacom Robusto Brown Sandblast 190 Pipe (CH009) £85.99 Davidoff 9mm Discovery Malawi Pipe (DAV03) £269.00 Hardcastle Argyle 101 Fishtail Pipe (H0049) £34.99 Hardcastle Briar Root 103 Checkerboard Fishtail Straight Pipe (H0025) £41.49 Hardcastle Camden 102 Smooth Fishtail Pipe (H0046) £52.99 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Apple Bent Pipe (LZ10) £220.00 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Unique Semi Bent Pipe (LZ08) £220.00 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1055) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 Fishtail Pipe (G1065) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 069 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1052) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 408 Fishtail Pipe (G1066) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1051) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 Fishtail Pipe (G1067) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent XL90 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1059) £69.99 Peterson Aran Smooth Pipe - 003 (G1034) £61.99 Peterson Around the World USA X105 Silver Mounted Pipe £79.99 Peterson Donegal Rocky Pipe - 003 (G1172) £65.99 Peterson Kinsale Curved Pipe XL15 (Squire) £83.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 120 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 305 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 338 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 408 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - B10 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 106 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 606 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - X220 £78.99 Peterson Liscannor Bent Pipe - X220 £43.99 Peterson Standard System Rustic 313 Pipe (SR005) £72.99 Peterson Standard System Smooth 302 Pipe (G1255) £72.99 Rattrays Limited Edition Turmeaus 1817 Green Pipe No. -

NH Convenient Database

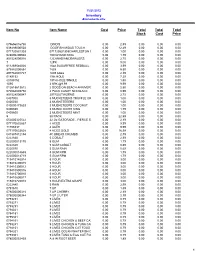

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

View the Exhibition Catalog

Chicana Badgirls Las Hociconas exhibition catalog CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................ 2 Delilah Montoya Con o Sin Permiso (With or Without Permission)...... 3-7 Laura E. Pérez Artists .................................................................... 8-25 Elia Arce ........................................... 12 Nao Bustamante ............................... 13 Marie Romero Cash .......................... 10 Diane Gamboa .................................. 19 Maya Gonzalez .................................. 8 Tina Hernández .................................. 9 Elisa Jiménez ..................................... 16 Alma López ...................................... 24 Pola López ........................................ 11 Amalia Mesa-Bains ........................... 22 Delilah Montoya ............................... 15 Chicana Badgirls: Las Hociconas Celia Alvarez Muñoz ......................... 14 Curated by Delilah Montoya & Laura E. Pérez Cecilia Portal ..................................... 18 Anita Rodríguez ................................ 25 January 17 - March 21, 2009 Isis Rodríguez .................................... 17 Maye Torres ...................................... 23 516 ARTS Consuelo Jiménez Underwood ......... 20 516 Central Avenue SW Rosa Zamora .................................... 21 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102 505-242-1445 www.516arts.org Artists’ Biographies .............................................. 26-28 Front Cover: Maya Gonzalez, Self-portrait Speaking Fire -

Download the Forecast Channel for the Wii and Keep the System Online, the Weather During the Game Will Reflect That of the Weather in Your Town Or City (Ex

Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None Unlockables Alternative Endings Depending on whether you save certain people during the course of the game, you'll receive one of 4 different endings. Unlockable How to Unlock Best Ending (Narracott, Get to Lombard before he dies, then attack Lombard and Claythorne murderer to save Claythorne. survive) Poor Ending (Narracott and Reach Lombard before he dies, and do not attack Lombard survive) the murderer. Reasonable Ending (Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, then attack and Claythorne survive) murderer to save Claythorne. Worst Ending (Only Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, and do not survives) attack the murderer. Alien Syndrome Unlockables Unlock Extra Difficulties In order to unlock the other two game difficulties, Hard and Expert, you must beat the game on the previous difficulty. Unlockable How to Unlock Unlock Expert Difficulty Beat the game on Hard Difficulty. Unlock Hard Difficulty Beat the game on Normal Difficulty. Animal Crossing: City Folk Unlockables Bank unlockables Deposit a certain amount of bells into bank. Unlockable How to Unlock Box of Tissues Deposit 100,000 bells into the bank. Gold Card Reach "VIP" status. Shopping Card Deposit 10,000 bells into the bank. Piggy Bank Deposit 10,000,000 Bells ------------------------------- Birthday cake Unlockable How to Unlock Birthday Cake Talk to your neighbors on your birthday ------------------------------- Harvest Set To get a furniture item from the Harvest Set, You must talk to Tortimer after 3pm on Harvest Day. He will give you a Fork and Knife pair, telling you that the 'Special Guest' hasn't shown up yet. -

Dia De Los Muertos Exhibition Ofrendas 2020 October 13 - November 27, 2020

Self Help Graphics & Art D Í A D E L O S M U E R T O S O F R E N D A S 2 0 2 0 O C T O B E R 1 3 - N O V E M B E R 2 7 FRONT COVER: SANDY RODRIGUEZ, GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ, AUTORRETRATO EN PANTEÓN, 2020, SERIGRAPH, SHG COMMEMORATIVE PRINT DIA DE LOS MUERTOS EXHIBITION OFRENDAS 2020 OCTOBER 13 - NOVEMBER 27, 2020 CURATED BY SANDY RODRIGUEZ NAO BUSTAMANTE ISABELLE LUTTERODT BARBARA CARRASCO RIGO MALDONADO CAROLYN CASTAÑO GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ ENRIQUE CASTREJON SANDY RODRIGUEZ YREINA CERVANTEZ SHIZU SALDAMANDO AUDREY CHAN GABRIELLA SANCHEZ CHRISTINA FERNANDEZ DEVON TSUNO CONSUELO FLORES YOUNG CENTER FOR IMMIGRANT CHILDREN'S SANDRA DE LA LOZA RIGHTS LEARN MORE AT WWW.SELFHELPGRAPHICS.COM/DIADELOSMUERTOS #SHGDOD DETAIL: GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ, SANDY RODRIGUEZ AND ELIZA RODRIGUEZ Y GIBSON, REUNION, 2020, ALTAR, VARIOUS MATERIALS, 25 X 25 X 10 FT. 4 INDEX 5 INDEX 7 CURATORIAL STATEMENT 9 OUR BELOVED DEAD: DIA DE 25 SANDRA DE LA LOZA LOS MUERTOS AND REVOLUTIONARY BY ELIZA 27 CHRISTINA FERNANDEZ RODRIGUEZ Y GIBSON 29 CONSUELO FLORES 11 THERE IS NOT ENOUGH TIME.., ONLY REALITY BY 31 ISABELLE LUTTERODT SYBIL VENEGAS 33 RIGO MALDONADO 13 NAO BUSTAMANTE 35 GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ 15 BARBARA CARRASCO 37 SANDY RODRIGUEZ 17 CAROLYN CASTAÑO 39 SHIZU SALDAMANDO 19 ENRIQUE CASTREJON 41 GABRIELLA SANCHEZ 21 YREINA CERVANTEZ 43 DEVON TSUNO 23 AUDREY CHAN 45 YOUNG CENTER FOR IMMIGRANT CHILDREN'S RIGHTS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 INSTALLATION VIEW: SANDY RODRIGUEZ 2020 COMMEMORATIVE PRINT, SANDY RODRIGUEZ AND GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ, MONARCHAS DE MUERTE, 2005, AND GUADALUPE RODRIGUEZ, AUTORRETRATOS EN EL PANTEON, 2003 6 CURATORIAL STATEMENT How do we come together to celebrate our ancestors and loved ones during a global pandemic? How do we create space for community when social distancing is critical amid rising infection numbers and deaths across our county and country? I am honored to have been invited to guest curate the Dia de los Muertos exhibition with Self Help Graphics for the 47th annual celebration in Los Angeles. -

JUNE 30, 1900. ICT&Jvsbsi CENTS

DS PORTLAND PRESS. S PRICK THREE ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. 39. PORTLAND, MAINE, SATURDAY MORNING, JUNE 30, 1900._ICT&jVSBSI CENTS. down the steep Incline of Mission hill un- KJCW ADVIHTlIMBm PRESIDENT OPTIMISTIC. der perfect control, as several pn*«-nger> Tklaki Ik. Tro.kl. la Cklu la All were taken on a short distance from the top. Probably by the breaking of a link "Q of the chain which engage* the winding Washington, Jane The President and controls the the car for bla Canton ASHORE. post brakes, le OREGON FROM SEYMOUR. quitting Washington gained headway rapidly and In a moment BIG CRT home full of oonndenoe that the tonight, It was moving at a frightful rate toward situation In China has improved though the vladuat under the railroad bridge. It it le fair to say that all the members of passed this In safety but at a turn In the his ofllolal family do not agree with him track the car left the rattled across in that oonoluskra. Indead the day's rails, III PRICES. the pavements, mounted tho ourbstoi • news limited though It was to a single and striking the market ploughed away Extraordinary trade* are cablegram from Admiral Kerapff and the 800 feet of the When the of lnetruotlons to Ueneral square bnlldlng. offered for One Week preparation America’s Most Famous Only. British Admiral Tells of Adven- oar stopped It was completely burled n set calculated to Battleship Story Chaffee, out nothing Russet button the market and tho motorman was vainly Children’* goat, strengthen the hope* of the friends of the tugging at the brake. -

2018 Sabbatical Research Newsletter

Brown Sabbatical Research Newsletter 2018 Foreword This is the sixth edition of the annual Brown Sabbatical Research Newsletter published by the Office of the Dean of the Faculty. Its main focus is on the research by Brown faculty that has been made possible during the past academic year by our sabbatical program (also included are some reports on non-sabbatical research). The word sabbatical derives from the Hebrew verb shabath meaning “to rest.” In keeping with the ancient Judeo-Christian concept the academic sabbatical designates a time, not of simple inactivity, but of the restorative intellectual activity of scholarship and research. Brown instituted the sabbatical leave in 1891, 11 years after Harvard had become the first university in the United States to introduce a system of paid research leaves (Brown was the fifth institution in the nation to adopt such a program, following Harvard, Cornell, Wellesley, and Columbia). As these dates suggest, the concept of the sabbatical emerged out of the establishment of the modern research university in America during the second half of the 19th century. A 1907 report by a Committee of the Trustees of Columbia University underlines the fundamental principle on which this innovation was based: “the practice now prevalent in Colleges and Universities of this country of granting periodic leaves of absence to their professors was established not in the interests of the professors themselves but for the good of university education” (cited in Eells, 253). Thus the restorative action of the sabbatical was understood to affect primarily not individual faculty members but the university as an intellectual community and an educational institution. -

Alexander Gray Associates

New York Alexander Gray Associates Germantown 510 West 26 Street 224 Main Street, Garden Level New York NY 10001 Germantown NY 12526 United States United States Tel: +1 212 399 2636 Tel: +1 518 537 2100 www.alexandergray.com COCO FUSCO Born 1960, New York, NY Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION PhD, 2007, Art & Visual Culture, Middlesex University, London, United Kingdom MA, 1985, Modern Thought and Literature, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA BA, 1982, Literature and Society / Semiotics, magna cum laude, Brown University, Providence, RI INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2019 Swimming on Dry Land/Nadar en seco, Flaten Art Museum, St. Olaf College, Northfield, MN 2018 Twilight, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, FL 2016 Coco Fusco, Alexander Gray Associates, New York, NY 2015 Coco Fusco: And the Sea will Talk to You, Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, England 2012 Coco Fusco, Alexander Gray Associates, New York, NY 2008 Buried Pig with Moros, The Project Gallery, New York, NY Operation Atropos, White Flag Projects, St. Louis, MO 2006 Operation Atropos, MC Projects, Los Angeles, CA 2004 A/K/A Mrs. George Gilbert, The Project Gallery, New York, NY 1992 The Year of the White Bear, in collaboration with Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Radio Pirata Broadcast on NPR and Pacifica radio; University of Colorado Artist Series, Denver, CO PERFORMANCES AND VIDEOS EXHIBITION HISTORY 2020 The Art of Intervention: The Performances of JuanSí González (video), NYU Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies, New York,