Special Publications the Museum Texas Tech University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Download the Spell of Egypt

The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens Etext prepared by Dagny, [email protected] and John Bickers, [email protected] PREPARER'S NOTE This text was prepared from a 1911 edition, published by The Century Co., New York. The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens CONTENTS THE PYRAMIDS THE SPHINX SAKKARA page 1 / 128 ABYDOS THE NILE DENDERAH KARNAK LUXOR COLOSSI OF MEMNON MEDINET-ABU THE RAMESSEUM DEIR-EL-BAHARI THE TOMBS OF THE KINGS EDFU KOM OMBOS PHILAE "PHARAOH'S BED" OLD CAIRO I THE PYRAMIDS Why do you come to Egypt? Do you come to gain a dream, or to regain lost dreams of old; to gild your life with the drowsy gold of romance, to lose a creeping sorrow, to forget that too many of your hours are sullen, grey, bereft? What do you wish of Egypt? The Sphinx will not ask you, will not care. The Pyramids, lifting page 2 / 128 their unnumbered stones to the clear and wonderful skies, have held, still hold, their secrets; but they do not seek for yours. The terrific temples, the hot, mysterious tombs, odorous of the dead desires of men, crouching in and under the immeasurable sands, will muck you with their brooding silence, with their dim and sombre repose. The brown children of the Nile, the toilers who sing their antique songs by the shadoof and the sakieh, the dragomans, the smiling goblin merchants, the Bedouins who lead your camel into the pale recesses of the dunes--these will not trouble themselves about your deep desires, your perhaps yearning hunger of the heart and the imagination. -

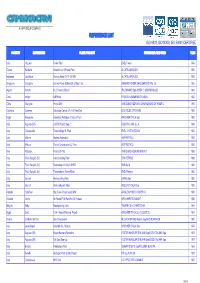

CAMUNA CAVI REFERENCE LIST 080818.Xlsx

A LAPP GROUP COMPANY REFERENCE LIST ISO 9001, ISO14000, ISO 50001 CERTIFIED COUNTRY DESTINATION PLANT / PROJECT PURCHASER / END USER YEAR Italy Vezzano Power Plant ENEL Trento 1994 Greece Keratsini Keratsini Unit 8 Power Plant ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Indonesia Java Barat Gunung Salak G.P.P. 55 MW ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Singapore Singapore Senoko Power station Ext. of Gas Turb. SIEMENS/POWER GEN. (SENOKO) Pte. Ltd. 1995 Algeria Annata No.2 Furnace Ribuild ITALIMPIANTI SpA/SIDER C. SIDERURGIQUE 1996 China Ningbo NZP Plant FROESCHL/SIEMENS ERLAGEN 1996 China Shanghai Project D68 SINCO ENGINEERING/ CHINAYIZHENG CH. FIBER C 1996 Colombia Covenas Oleoducto Central S.A. Full Field Dev. BOUYGUES OFFSHORE 1996 Egypt Alexandria Alexandria Petroleum Crude Oil Furn. KIRCHNER ITALIA Spa 1996 Italy Augusta (SR) LSADO Project Step 2 ESSO ITALIANA S.p.A. 1996 Italy Civitavecchia Torrevaldaliga N. Plant ENEL- CIVITAVECCHIA 1996 Italy Milazzo Heaters Automation AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Milazzo Control Centralization LC-Finer AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Pallanza Project CF-762 SINCO ENGINEERING/ITALPET 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Interconnecting Plant ERG PETROLI 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Revamping Unit 200 A NHDS ISAB S.p.A. 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Thermoelectric Power Plant ENEL-Palermo 1996 Italy Sarroch Hydrocracking Plant SARAS Spa 1996 Italy Sarroch Intrinsically-safe Plant HOECHST ITALIA Spa 1996 Pakistan Hub River Hub Power Project 4x323 MW ANSALDO/HUBCO POWER Co 1996 S.Arabia Yanbu Ibn Rushd/PTA Plant Hot Oil Furnace KIRCHNER/TECNIMONT 1996 Belgium Feluy Manufacturing Units TELEREX S.A. / PANTOCHIM 1997 Egypt Suez 10 H-1 Heater Revamp. Project KIRCHNER ITALIA S.p.A./ SUEZ OIL 1997 France St. -

The Case of New Gourna

K. Galal Ahmed & L. El-Gizawy, Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. Vol. 5, No. 4 (2010) 407–429 THE DILEMMA OF SUSTAINABILITY IN THE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS OF RURAL COMMUNITIES IN EGYPT – THE CASE OF NEW GOURNA K. GALAL AHMED1 & L. EL-GIZAWY2 1Department of Architectural Engineering, United Arab Emirates University, UAE. 2Department of Architectural Engineering, Mansoura University, Egypt. ABSTRACT Gourna, a vernacular village in Upper Egypt, was built over a Pharonic heritage site. During the 1940s, and in order to protect the monuments from theft, the Egyptian government commissioned the renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy to design a new settlement for the Gournii. Despite the great effort exerted by Fathy to design The New Gourna in an environmentally and socially responsive manner, the project had consider- ably failed as most of the residents refused to move to the new village. Recently, the government repeated the attempt but this time the second version of the New Gourna came significantly different. In order to force them to move, the government demolished most of the houses of the residents of Gourna and left only a few houses to be re-used as museums for the vernacular architecture of the village. The main objective of the paper is to investigate if the second version of the New Gourna is going to overcome the sustainability problems associated with Fathy’s New Gourna and if it is going to deal successfully with the sustainable vernacular architecture of the region. In order to undertake this investigation the paper first reviews the vernacular architecture of Gourna and then discusses both Fathy’s approach and the recent New Gourna village’s approach from the sustainabil- ity point of view. -

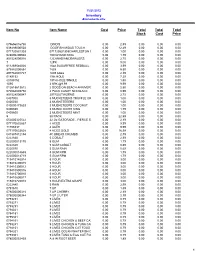

Pipes Adsorba Pipes Alba Pipes

Prices correct at time of printing 26/09/2018 SPECIAL OFFERS - Pipes Black Swan 46 Rattrays Pipe £109.99 Chacom Robusto Brown Sandblast 190 Pipe (CH009) £85.99 Davidoff 9mm Discovery Malawi Pipe (DAV03) £269.00 Hardcastle Argyle 101 Fishtail Pipe (H0049) £34.99 Hardcastle Briar Root 103 Checkerboard Fishtail Straight Pipe (H0025) £41.49 Hardcastle Camden 102 Smooth Fishtail Pipe (H0046) £52.99 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Apple Bent Pipe (LZ10) £220.00 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Unique Semi Bent Pipe (LZ08) £220.00 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1055) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 Fishtail Pipe (G1065) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 069 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1052) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 408 Fishtail Pipe (G1066) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1051) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 Fishtail Pipe (G1067) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent XL90 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1059) £69.99 Peterson Aran Smooth Pipe - 003 (G1034) £61.99 Peterson Around the World USA X105 Silver Mounted Pipe £79.99 Peterson Donegal Rocky Pipe - 003 (G1172) £65.99 Peterson Kinsale Curved Pipe XL15 (Squire) £83.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 120 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 305 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 338 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 408 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - B10 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 106 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 606 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - X220 £78.99 Peterson Liscannor Bent Pipe - X220 £43.99 Peterson Standard System Rustic 313 Pipe (SR005) £72.99 Peterson Standard System Smooth 302 Pipe (G1255) £72.99 Rattrays Limited Edition Turmeaus 1817 Green Pipe No. -

Ahmose, Son of Ebana: the Expulsion of the Hyksos

Ahmose, son of Ebana: The Expulsion of the Hyksos Ahmose, son of Ebana, was an officer in the Egyptian army during the end of the 17th Dynasty to the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (16th century BCE). Originally from Elkab in Upper Egypt, he decided to become a soldier, like his father, Baba, who served under Seqenenre Tao II in the early campaigns against the Hyksos. Ahmose spent most of his military life serving aboard the king’s fleet - fighting at Avaris, at Sharuhen in Palestine, and in Nubia during the service of Ahmose I, and was often cited for his bravery in battle by the king. These accounts were left in a tomb that Ahmose, son of Ebana, identifies as his own at the end of the water—for he was captured on the city side-and he Crew Commander Ahmose son of crossed the water carrying him. When it was Abana, the justified; he says: I speak reported to the royal herald I was rewarded with T to you, all people. I let you know gold once more. Then Avaris was despoiled, and what favors came to me. I have been I brought spoil from there: one man, three rewarded with gold seven times in the sight women; total, four persons. His majesty gave of the whole land, with male and female them to me as slaves. slaves as well. I have been endowed with Then Sharahen was besieged for three years. very many fields. The name of the brave His majesty despoiled it and I brought spoil man is in that which he has done; it will not from it: two women and a hand. -

NH Convenient Database

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

Embalming Caches

THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LO:'-JDON weIN 2PG ISSN 0307-5133 THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LONDON WCIN zPG CONTENTS TELL EL-AMARNA, 2007-8 Barry Kemp I THE PTOLEMAIC-RoMAN CEMETERY AT THE QUESNA ARCHAEOLOGICAL AREA Joanne Rowland I::\"TRODUCING TELL GABBARA: NEW EVIDENCE FOR EARLY DYNASTIC SETTLEMENT IN THE EASTERN DELTA Sabrina R. Rampersad . 95 THE COFFINS OF IYHAT AND TAIRY: A TALE OF Two CITIES Aidan Dodson . 1°7 .-\ GARLAND OF DETERMINATIVES Anthony J. Spalinger 139 A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSECTIVE ON EGYPTIAN COLONIALISM IN THE NEW KINGDOM . Michele R. Buzon 165 DIE DEMOTISCHEN STELEN AUS DER GEGEND YON HUSSANIYA/TELL NEBESHEH . Jan Moje a::\" THE PRESENCE OF DEER IN ANCIENT EGYPT: .-\NALYSIS OF THE OSTEOLOGICAL RECORD Chiori Kitagawa · 2°9 COLLECTING EGYPTIAN ANTIQUITIES IN THE YEAR 1838: REVEREND WILLIAM HODGE MILL Brian Muhs and .'-~D ROBERT CURZON, BARON ZOUCHE . Tashia Vorderstrasse · 223 THE NAOS OF 'BASTET, LADY OF THE SHRINE' FROM BUBASTIS Daniela Rosenow · 247 C::\"E BASE DE STATUE FRAGMENTAIRE DE SESOSTRIS pR PROVENANT DE DRA ABOU EL-NAGA David Lorand BRiEF COMMUNICATIONS THE SOUNDS OF rAIN IN EGYPTIAN, GREEK, COPTIC, AND ARABIC . Anthony Alcock. · 275 BDIERKUNGEN ZU ZWEI USURPIERTE SAULEN .-\1:5 DER ZEIT MERENPTAHS Y oshifumi Yasuoka . A ROCK ART PALIMPSEST: EVIDENCE OF THE RELHIVE AGES OF SOME EASTERN DESERT PETROGLYPHS . Tony Judd. 282 E. IB.-\L\lING CACHES. Marianne Eaton-Krauss. 288 _-\ '\"ERLAN' SCRIBE IN DEIR EL-BERSHA: ~ O:\IE DEMOTIC INSCRIPTIONS ON QC.-\RRY CEILINGS. -

Rousettus Aegyptiacus (Pteropodidae) in the Palaearctic: List of Records and Revision of the Distribution Range*

Vespertilio 15: 3–36, 2011 ISSN 1213-6123 Rousettus aegyptiacus (Pteropodidae) in the Palaearctic: list of records and revision of the distribution range* Petr BENDA1,2, Mounir ABI-SAID3, Tomáš Bartonička4, Raşit BILGIN5, Kaveh FAIZOLAHI6, Radek K. Lučan2, Haris NICOLAOU7, Antonín REITER8, Wael M. SHOHDI9, Marcel UHRIN10 & Ivan Horáček2 1 Department of Zoology, National Museum (Natural History), Václavské nám. 68, CZ–115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 7, CZ–128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic 3 Department of Biology, American University of Beirut, Riadh El Solh 1107, 2020 Beirut, Lebanon 4 Department of Botany and Zoology, Masaryk University, Kotlářská 2, CZ–611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Bogazici University, Bebek, TR–34342 Istanbul, Turkey 6 Mohitban Society, 2010 Mitra Alley, Shariati Street, Tehran, 1963816163, Iran 7 Forestry Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, Louki Akrita 24, Nicosia, Cyprus 8 South Moravian Museum in Znojmo, Přemyslovců 8, CZ–669 45 Znojmo, Czech Republic 9 Nature Conservation Egypt & Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt 10 Institute of Biology and Ecology, P. J. Šafárik University, Moyzesova 11, SK–040 01 Košice, Slovakia Abstract. The populations of Rousettus aegyptiacus inhabiting the Palaearctic part of the species range represent the only offshoot of the family Pteropodidae beyond tropics. In this contribution, we revised distribution status of the species in different parts of its Palaearctic range, re-examined the literature data and supplemented them with an extensive set of original records obtained in the field during the last two decades. -

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume

class93% BO~~BVR Library of ~delbertCollege V.3 of Western Rerane Unlvsrsity, Olsvoiand. 0. ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT ANCIENT RECORDS UNDER THE GENERAL EDITORSHIP OF WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA EDITED BY ROBERT FRANCIS HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT EDITED BY JAMES HENRY. BREARTED ANCIENT RECORDS OF PALESTINE, PH(EN1CIA AND SYRIA EDITED BY WILLIAM RAINEX HARPEB ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE PERSIAN CONQUEST. COLLECTED EDITED AND TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY JAMES HENRY BREASTED, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF EGYPTOLOGY AND ORIENTAL HISTORY IN TIIE UNIVBEWTY OF CHICAGO VOLUME I11 WHE NINETEENTH DYNASTY CHICAGO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1906 LONDON: LUZAC & CO. LEIPZIGI : OTTO HABRASSOWITZ Published May 1906 QLC.%, Composed and Printed By The University of Chicago Press Chicago. Illinois. U. S. A. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I THEDOCUMENTARY SOURCES OF EGYPTIANHISTORY . CHRONOLOGY........... CHRONOLOGICALTABLE ........ THEPALERMO STONE: THE FIRST TO THE FIFTH DYNASTIES I. Predynastic Kings ........ I1. First Dynasty ......... 111. Second Dynasty ........ IV. Third Dynasty ......... V . Fourth Dynasty ........ VI . Fifth Dynasty ......... THETHIRD DYNASTY ........ Reign of Snefru ...s . b ;- .... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Biography of Methen ........ THE FOURTHDYNASTY ........ Reign of Khufu ......... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Inventory Stela ......... Examples of Dedication Inscriptions by Sons . Reign of Khafre ......... Stela of Mertitydtes ........ Will of Prince Nekure. Son of King Khafre ... Testamentary Enactment of an Unknown Official. Establishing the Endowment of His Tomb by the Pyramid of Khafre ........ Reign of Menkure ......... Debhen's Inscription. Recounting King Menkure's Erec- tion of a Tomb for Him ....... TEE RFTHDYNASTY ......... Reign of Userkaf ......... v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Testamentary Enactment of Nekonekh .... I. -

Download the Forecast Channel for the Wii and Keep the System Online, the Weather During the Game Will Reflect That of the Weather in Your Town Or City (Ex

Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None Unlockables Alternative Endings Depending on whether you save certain people during the course of the game, you'll receive one of 4 different endings. Unlockable How to Unlock Best Ending (Narracott, Get to Lombard before he dies, then attack Lombard and Claythorne murderer to save Claythorne. survive) Poor Ending (Narracott and Reach Lombard before he dies, and do not attack Lombard survive) the murderer. Reasonable Ending (Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, then attack and Claythorne survive) murderer to save Claythorne. Worst Ending (Only Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, and do not survives) attack the murderer. Alien Syndrome Unlockables Unlock Extra Difficulties In order to unlock the other two game difficulties, Hard and Expert, you must beat the game on the previous difficulty. Unlockable How to Unlock Unlock Expert Difficulty Beat the game on Hard Difficulty. Unlock Hard Difficulty Beat the game on Normal Difficulty. Animal Crossing: City Folk Unlockables Bank unlockables Deposit a certain amount of bells into bank. Unlockable How to Unlock Box of Tissues Deposit 100,000 bells into the bank. Gold Card Reach "VIP" status. Shopping Card Deposit 10,000 bells into the bank. Piggy Bank Deposit 10,000,000 Bells ------------------------------- Birthday cake Unlockable How to Unlock Birthday Cake Talk to your neighbors on your birthday ------------------------------- Harvest Set To get a furniture item from the Harvest Set, You must talk to Tortimer after 3pm on Harvest Day. He will give you a Fork and Knife pair, telling you that the 'Special Guest' hasn't shown up yet. -

JUNE 30, 1900. ICT&Jvsbsi CENTS

DS PORTLAND PRESS. S PRICK THREE ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. 39. PORTLAND, MAINE, SATURDAY MORNING, JUNE 30, 1900._ICT&jVSBSI CENTS. down the steep Incline of Mission hill un- KJCW ADVIHTlIMBm PRESIDENT OPTIMISTIC. der perfect control, as several pn*«-nger> Tklaki Ik. Tro.kl. la Cklu la All were taken on a short distance from the top. Probably by the breaking of a link "Q of the chain which engage* the winding Washington, Jane The President and controls the the car for bla Canton ASHORE. post brakes, le OREGON FROM SEYMOUR. quitting Washington gained headway rapidly and In a moment BIG CRT home full of oonndenoe that the tonight, It was moving at a frightful rate toward situation In China has improved though the vladuat under the railroad bridge. It it le fair to say that all the members of passed this In safety but at a turn In the his ofllolal family do not agree with him track the car left the rattled across in that oonoluskra. Indead the day's rails, III PRICES. the pavements, mounted tho ourbstoi • news limited though It was to a single and striking the market ploughed away Extraordinary trade* are cablegram from Admiral Kerapff and the 800 feet of the When the of lnetruotlons to Ueneral square bnlldlng. offered for One Week preparation America’s Most Famous Only. British Admiral Tells of Adven- oar stopped It was completely burled n set calculated to Battleship Story Chaffee, out nothing Russet button the market and tho motorman was vainly Children’* goat, strengthen the hope* of the friends of the tugging at the brake.