A Few Fragments of Qurna History from Tarif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theban Necropolis Preservation Initiative

THE THEBAN NECROPOLIS PRESERVATION INITIATIVE FACTUM FOUNDATION AND THE UNIVERSITY OF BASEL WORKING WITH THE MINISTRY OF TOURISM AND ANTIQUITIES A REPORT ON THE WORK COMPLETED IN THE TOMB OF SETI I UP TO SEPTEMBER 2020 2 1 THE THEBAN NECROPOLIS PRESERVATION INITIATIVE FACTUM FOUNDATION AND THE UNIVERSITY OF BASEL WORKING WITH THE MINISTRY OF TOURISM AND ANTIQUITIES A REPORT ON THE WORK COMPLETED IN THE TOMB OF SETI I UP TO SEPTEMBER 2020 Under the patronage of Detail from the ceiling of the Sarcophagus Room in the tomb of Seti I, recorded in 2019. TABLE OF CONTENTS This book is dedicated to the memory of Ayman THE THEBAN NECROPOLIS PRESERVATION INITIATIVE 5 Introduction 5 Mohamed Ibrahim, the former inspector of the Recording Progress: Lucida 3D Scanner 8 Valley of the Kings who understood the importance Recording Progress: Photogrammetry 10 of the work of the Theban Necropolis Preservation Recording Progress: Panoramic Colour Photography 12 Initiative and spoke about it with eloquence. Recording Progress: LiDAR 3D Scanning 14 Background: work in Luxor since 2001 19 Aims of the TNPI 22 The 3D Scanning, Training and Archiving Centre 25 Team Members: selected biographies 26 Training Program: September 2019 - September 2020 29 Scanning completed in the Tomb of Seti, September 2019- September 2020 31 Recording the fragments of the Tomb of Seti I 33 “The educational impact [of Factum’s digitisations and A new use for a facsimile in the Theban Necropolis: a collaboration with CSIC 37 facsimiles] for the general public is indisputible: now Summary of current position and future steps September 2019 - September 2020 39 scholars have to face the challenge of inserting these new SYSTEMS FOR DATA CAPTURE, PROCESSING AND STORAGE 43 tools into their research and exploiting their potential, LiDAR 45 before they are once more outwitted by commercial Lucida 3D Scanner 47 applications. -

SEDJM SPRING 2008.Pdf

SEDJEM The Newsletter of the Orange County Chapter Spring 2008 of the American Research Center In Egypt Event Update: 2008 continues to be an exciting year for Egyptology in Southern California. Tickets are still available (registration form inside), for the chapter's day long June 7 seminar on Ancient Egyptian Medical and Magical Practices. Dr. Robert Ritner, who has trained generations of Egyptologists, is coming out from the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago especially to teach this class. The weekend of August 23 - 24 is huge for Southern California. On Saturday, August 23, the headline making husband and wife team from the Colossi of Memnon Project will speak to OC ARCE . Both Drs. Hourig Sourouzian and Rainer Stadelmann will speak and take questions. See the details inside the newsletter, BUT PLEASE CORRECT YOUR CALENDARS, AS THIS EVENT WAS ORIGINALLY LISTED AS AUGUST 25. The next day, August 24, Dr. Zahi Hawass, Director General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, and star of countless TV specials, will speak at the Bowers, in a museum sponsored event. In his only Southern Californian appearance this fall, his topic will be the Pharaoh Hatshepsut, and the results of recent DNA testing and new archaeological discoveries in her re-excavated tomb. (And just maybe he will answer some questions about the speculation that a new tomb, which would be KV 64, has been discovered in the Valley of the Kings.) This is a two tiered event, with a reception beginning at 5 PM and the lecture at 6 PM. Tickets for both are $50, and for the lecture only are $30. -

Submitted, Accepted and Published By

*Revised Manuscript (clean copy) Click here to download Revised Manuscript (clean copy): Bardaji et al_01-17.docx Click here to view linked References 1 Geomorphology of Dra Abu el-Naga (Egypt): the basis of the funerary sacred 2 landscape 3 Bardají, T.1, Martinez-Graña, A.2, Sánchez Moral, S.3, Pethen, H.4, García- 4 González, D.5, Cuezva, S.6, Cañaveras, J.C.7, Jiménez-Higueras, A.4 5 1. Dpto. de Geología, Geografía y Medio Ambiente; Univ. de Alcalá; 28871- Alcalá de 6 Henares (Spain). Corresponding author: [email protected] 7 2. Dpto. Geología, Univ. de Salamanca; 37008-Salamanca (Spain). 8 3. Dpto. de Geología, MNCN-CSIC; 28006-Madrid (Spain). 9 4. School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool; L69 7WZ- 10 Liverpool (U.K.) 11 5. CCHS-CSIC. Research Project HAR2014/52323-P; 28037-Madrid (Spain). 12 6. Geomnia Natural Resources SLNE, 28003-Madrid (Spain) 13 7. Dpto. de Ciencias de la Tierra y del Medioambiente, Univ. de Alicante; 03690-Alicante 14 (Spain). 15 16 Abstract 17 A geological and geomorphological analysis has been performed in the necropolis of 18 Dra Abu el-Naga in order to understand the role played by these two factors in the 19 development of the sacred landscape. The investigation focuses upon two aspects of 20 the development of the necropolis, the selection criteria for tomb location and the 21 reconstruction of the ancient funerary landscape. Around 50 tombs were surveyed, 22 analysing the characteristics of their host rock and classifying them according to a 23 modified Rock Mass Rating Index, in order to understand how rock quality affected 24 tomb construction. -

Download the Spell of Egypt

The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens Etext prepared by Dagny, [email protected] and John Bickers, [email protected] PREPARER'S NOTE This text was prepared from a 1911 edition, published by The Century Co., New York. The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens CONTENTS THE PYRAMIDS THE SPHINX SAKKARA page 1 / 128 ABYDOS THE NILE DENDERAH KARNAK LUXOR COLOSSI OF MEMNON MEDINET-ABU THE RAMESSEUM DEIR-EL-BAHARI THE TOMBS OF THE KINGS EDFU KOM OMBOS PHILAE "PHARAOH'S BED" OLD CAIRO I THE PYRAMIDS Why do you come to Egypt? Do you come to gain a dream, or to regain lost dreams of old; to gild your life with the drowsy gold of romance, to lose a creeping sorrow, to forget that too many of your hours are sullen, grey, bereft? What do you wish of Egypt? The Sphinx will not ask you, will not care. The Pyramids, lifting page 2 / 128 their unnumbered stones to the clear and wonderful skies, have held, still hold, their secrets; but they do not seek for yours. The terrific temples, the hot, mysterious tombs, odorous of the dead desires of men, crouching in and under the immeasurable sands, will muck you with their brooding silence, with their dim and sombre repose. The brown children of the Nile, the toilers who sing their antique songs by the shadoof and the sakieh, the dragomans, the smiling goblin merchants, the Bedouins who lead your camel into the pale recesses of the dunes--these will not trouble themselves about your deep desires, your perhaps yearning hunger of the heart and the imagination. -

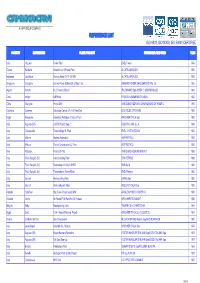

CAMUNA CAVI REFERENCE LIST 080818.Xlsx

A LAPP GROUP COMPANY REFERENCE LIST ISO 9001, ISO14000, ISO 50001 CERTIFIED COUNTRY DESTINATION PLANT / PROJECT PURCHASER / END USER YEAR Italy Vezzano Power Plant ENEL Trento 1994 Greece Keratsini Keratsini Unit 8 Power Plant ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Indonesia Java Barat Gunung Salak G.P.P. 55 MW ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Singapore Singapore Senoko Power station Ext. of Gas Turb. SIEMENS/POWER GEN. (SENOKO) Pte. Ltd. 1995 Algeria Annata No.2 Furnace Ribuild ITALIMPIANTI SpA/SIDER C. SIDERURGIQUE 1996 China Ningbo NZP Plant FROESCHL/SIEMENS ERLAGEN 1996 China Shanghai Project D68 SINCO ENGINEERING/ CHINAYIZHENG CH. FIBER C 1996 Colombia Covenas Oleoducto Central S.A. Full Field Dev. BOUYGUES OFFSHORE 1996 Egypt Alexandria Alexandria Petroleum Crude Oil Furn. KIRCHNER ITALIA Spa 1996 Italy Augusta (SR) LSADO Project Step 2 ESSO ITALIANA S.p.A. 1996 Italy Civitavecchia Torrevaldaliga N. Plant ENEL- CIVITAVECCHIA 1996 Italy Milazzo Heaters Automation AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Milazzo Control Centralization LC-Finer AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Pallanza Project CF-762 SINCO ENGINEERING/ITALPET 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Interconnecting Plant ERG PETROLI 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Revamping Unit 200 A NHDS ISAB S.p.A. 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Thermoelectric Power Plant ENEL-Palermo 1996 Italy Sarroch Hydrocracking Plant SARAS Spa 1996 Italy Sarroch Intrinsically-safe Plant HOECHST ITALIA Spa 1996 Pakistan Hub River Hub Power Project 4x323 MW ANSALDO/HUBCO POWER Co 1996 S.Arabia Yanbu Ibn Rushd/PTA Plant Hot Oil Furnace KIRCHNER/TECNIMONT 1996 Belgium Feluy Manufacturing Units TELEREX S.A. / PANTOCHIM 1997 Egypt Suez 10 H-1 Heater Revamp. Project KIRCHNER ITALIA S.p.A./ SUEZ OIL 1997 France St. -

PERSPECTIVES on PTOLEMAIC THEBES Oi.Uchicago.Edu Ii

oi.uchicago.edu i PERSPECTIVES ON PTOLEMAIC THEBES oi.uchicago.edu ii Pre-conference warm-up at Lucky Strike in Chicago. Standing, left to right: Joseph Manning, Ian Moyer, Carolin Arlt, Sabine Albersmeier, Janet Johnson, Richard Jasnow Kneeling: Peter Dorman, Betsy Bryan oi.uchicago.edu iii O CCASIONAL PROCEEdINgS Of THE THEBAN WORkSHOP PERSPECTIVES ON PTOLEMAIC THEBES edited by Pete R F. DoRMAn and BetSy M. BRyAn Papers from the theban Workshop 2006 StuDIeS In AnCIent oRIentAL CIvILIzAtIon • nuMBeR 65 the oRIentAL InStItute oF the unIveRSIty oF ChICAgo ChICAgo • ILLInois oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2001012345 ISBN-10: 1-885923-85-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-85-1 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. studIeS IN ANCIeNT orIeNTAL CIvILIzATIoN • NUmBer 65 The orIeNTAL INSTITUTe of The UNIverSITy of ChICAgo Chicago • Illinois Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas g. Urban Series Editors’ Acknowledgments rebecca Cain, françois gaudard, foy Scalf, and Natalie Whiting assisted in the production of this volume. Cover and Title Page Illustration Part of a cosmogonical inscription of Ptolemy vIII euergetes II at Medinet habu (Mh.B 155). Photo by J. Brett McClain Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library materials, ANSI z39.48-1984. -

Steam Ship Sudan 2020-Enga

The Steam Ship Sudan, an authentic steamship built at the dawn of the 20th century, brings turn-of-the-century travel to life again. THE DYNASTIC Luxor to Aswan 6 days – 5 nights D1 – LUXOR TO QENA Transfer to the ship. Settle in on board and into your cabin. Lunch on board. Afternoon visit of Luxor’s east bank through the discovery of the Karnak Temple Complex, one of the largest sacred site in the world ; it especially comprises the Temple of Amun, the patron deity of Karnak. Its construction lasted from the Middle Kingdom till the Ptoleamic Kingdom. Visit of the Temple of Luxor. Built under Amenophis III and extended under Ramesses II, the Temple of Luxor is the most elegant pharaonic building. Sailing towards Qena, located north of Luxor. Only a few ships sail this splendid stretch of the river Nile where you will be able to enjoy the sunset and admire both banks of the Nile. Dinner and overnight stay on board in Qena. D2– QENA / DENDERA / ABYDOS / LUXOR Early start (2 hours drive) to Abydos, a holy city and the cult centre of Osiris, regent of the Kingdom of the Dead and god of resurrection. From the Ancient Kingdom era, Abydos was an exceptional site of pilgrimage. The Temple of Seti I is a wonder with its colourful and fine bas-reliefs which mark the birth of Ramesside art. Visit of the Temple of Dendera on the way back. Dendera is the name of the spectacular temple of Hathor, Goddess of love and joy, also known for protecting women and nursing Pharaohs. -

The Case of New Gourna

K. Galal Ahmed & L. El-Gizawy, Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. Vol. 5, No. 4 (2010) 407–429 THE DILEMMA OF SUSTAINABILITY IN THE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS OF RURAL COMMUNITIES IN EGYPT – THE CASE OF NEW GOURNA K. GALAL AHMED1 & L. EL-GIZAWY2 1Department of Architectural Engineering, United Arab Emirates University, UAE. 2Department of Architectural Engineering, Mansoura University, Egypt. ABSTRACT Gourna, a vernacular village in Upper Egypt, was built over a Pharonic heritage site. During the 1940s, and in order to protect the monuments from theft, the Egyptian government commissioned the renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy to design a new settlement for the Gournii. Despite the great effort exerted by Fathy to design The New Gourna in an environmentally and socially responsive manner, the project had consider- ably failed as most of the residents refused to move to the new village. Recently, the government repeated the attempt but this time the second version of the New Gourna came significantly different. In order to force them to move, the government demolished most of the houses of the residents of Gourna and left only a few houses to be re-used as museums for the vernacular architecture of the village. The main objective of the paper is to investigate if the second version of the New Gourna is going to overcome the sustainability problems associated with Fathy’s New Gourna and if it is going to deal successfully with the sustainable vernacular architecture of the region. In order to undertake this investigation the paper first reviews the vernacular architecture of Gourna and then discusses both Fathy’s approach and the recent New Gourna village’s approach from the sustainabil- ity point of view. -

(Modern Luxor) Ancient Greek Name for the Upper Egyptian Town of Waset

Originalveröffentlichung in: Donald B. Redford (Hrsg.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt III, Oxford 2001, S. 384-388 384 THEBES complexes, extended over an area of more than 4 kilo meters (2.4 miles) in length and 0.51 kilometer (about a quarter to a half mile) in width. The great number of monuments, many exceptionally well preserved, make the Theban area the largest and most important archaeologi cal site in Egypt. Eastern Bank of the Nile. A discussion of the princi pal archaeological features follows. The temple of Karnak. Archaeologically, the eastern bank of Thebes is dominated by the gigantic temple com plex of Karnak, the home of Egypt's main god AmunRe from the time of the Middle Kingdom onward. The earli est known parts of the temple have been dated to the first half of the eleventh dynasty, when a presumably modest temple, or a chapel, for the god Amun was erected by King Antef II. The temple was substantially expanded in the twelfth dynasty, during the reign of Senwosret L The temple, however, seems to have remained in this state for almost four hundred years. From the eighteenth dynasty until the Roman period, Karnak was a place of continu ous building activity, but of varying intensity. The temple of Luxor. The main part of the temple of Luxor was founded by Amenhotpe III (r. 14101372 BCE). An earlier triple shrine (barkstation), built by Queen Hat shepsut and Thutmose III (r. 15021452 BCE) north of the first pylon, remained in use at later times; then in the nineteenth dynasty, Ramesses II added an open court to the north of the existing Amenhotpe III building. -

Ahmose, Son of Ebana: the Expulsion of the Hyksos

Ahmose, son of Ebana: The Expulsion of the Hyksos Ahmose, son of Ebana, was an officer in the Egyptian army during the end of the 17th Dynasty to the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (16th century BCE). Originally from Elkab in Upper Egypt, he decided to become a soldier, like his father, Baba, who served under Seqenenre Tao II in the early campaigns against the Hyksos. Ahmose spent most of his military life serving aboard the king’s fleet - fighting at Avaris, at Sharuhen in Palestine, and in Nubia during the service of Ahmose I, and was often cited for his bravery in battle by the king. These accounts were left in a tomb that Ahmose, son of Ebana, identifies as his own at the end of the water—for he was captured on the city side-and he Crew Commander Ahmose son of crossed the water carrying him. When it was Abana, the justified; he says: I speak reported to the royal herald I was rewarded with T to you, all people. I let you know gold once more. Then Avaris was despoiled, and what favors came to me. I have been I brought spoil from there: one man, three rewarded with gold seven times in the sight women; total, four persons. His majesty gave of the whole land, with male and female them to me as slaves. slaves as well. I have been endowed with Then Sharahen was besieged for three years. very many fields. The name of the brave His majesty despoiled it and I brought spoil man is in that which he has done; it will not from it: two women and a hand. -

Embalming Caches

THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LO:'-JDON weIN 2PG ISSN 0307-5133 THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LONDON WCIN zPG CONTENTS TELL EL-AMARNA, 2007-8 Barry Kemp I THE PTOLEMAIC-RoMAN CEMETERY AT THE QUESNA ARCHAEOLOGICAL AREA Joanne Rowland I::\"TRODUCING TELL GABBARA: NEW EVIDENCE FOR EARLY DYNASTIC SETTLEMENT IN THE EASTERN DELTA Sabrina R. Rampersad . 95 THE COFFINS OF IYHAT AND TAIRY: A TALE OF Two CITIES Aidan Dodson . 1°7 .-\ GARLAND OF DETERMINATIVES Anthony J. Spalinger 139 A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSECTIVE ON EGYPTIAN COLONIALISM IN THE NEW KINGDOM . Michele R. Buzon 165 DIE DEMOTISCHEN STELEN AUS DER GEGEND YON HUSSANIYA/TELL NEBESHEH . Jan Moje a::\" THE PRESENCE OF DEER IN ANCIENT EGYPT: .-\NALYSIS OF THE OSTEOLOGICAL RECORD Chiori Kitagawa · 2°9 COLLECTING EGYPTIAN ANTIQUITIES IN THE YEAR 1838: REVEREND WILLIAM HODGE MILL Brian Muhs and .'-~D ROBERT CURZON, BARON ZOUCHE . Tashia Vorderstrasse · 223 THE NAOS OF 'BASTET, LADY OF THE SHRINE' FROM BUBASTIS Daniela Rosenow · 247 C::\"E BASE DE STATUE FRAGMENTAIRE DE SESOSTRIS pR PROVENANT DE DRA ABOU EL-NAGA David Lorand BRiEF COMMUNICATIONS THE SOUNDS OF rAIN IN EGYPTIAN, GREEK, COPTIC, AND ARABIC . Anthony Alcock. · 275 BDIERKUNGEN ZU ZWEI USURPIERTE SAULEN .-\1:5 DER ZEIT MERENPTAHS Y oshifumi Yasuoka . A ROCK ART PALIMPSEST: EVIDENCE OF THE RELHIVE AGES OF SOME EASTERN DESERT PETROGLYPHS . Tony Judd. 282 E. IB.-\L\lING CACHES. Marianne Eaton-Krauss. 288 _-\ '\"ERLAN' SCRIBE IN DEIR EL-BERSHA: ~ O:\IE DEMOTIC INSCRIPTIONS ON QC.-\RRY CEILINGS. -

The Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus a New Edition, Translation, and Interpretation

THE RAMESSEUM DRAMATIC PAPYRUS A NEW EDITION, TRANSLATION, AND INTERPRETATION by Christina Geisen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Christina Geisen (2012) Abstract Thesis Title: The Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus. A new edition, translation, and interpretation Degree: PhD Year of Convocation: 2012 Name: Christina Geisen Graduate Department: Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University: University of Toronto The topic of the dissertation is a study of the Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus, a document that was discovered together with other papyri and funerary objects in a late Middle Kingdom tomb in the necropolis later associated with Ramses II’s funerary temple on the West bank of Luxor. The thesis will cover an analysis of the complete find, providing information on the provenance of the collection, the circumstances of its discovery, the dating of the papyri, and the identity of the tomb owner. The focus of the dissertation, however, is the Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus itself, which features the guideline for the performance of a ritual. The fabrication and preservation of the manuscript is described as well as the layout of the text. Based on a copy of the original text made with the help of a tablet PC, an up-dated transliteration and translation of the text is provided, accompanied by a commentary. The text has been studied by several scholars, but a convincing interpretation of the manuscript is lacking. Thus, the dissertation will analyse the previous works on the papyrus, and will compare the activities described in the text of the manuscript with other attested rituals from ii ancient Egypt.