The Case of New Gourna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Spell of Egypt

The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens Etext prepared by Dagny, [email protected] and John Bickers, [email protected] PREPARER'S NOTE This text was prepared from a 1911 edition, published by The Century Co., New York. The Spell of Egypt by Robert Hichens CONTENTS THE PYRAMIDS THE SPHINX SAKKARA page 1 / 128 ABYDOS THE NILE DENDERAH KARNAK LUXOR COLOSSI OF MEMNON MEDINET-ABU THE RAMESSEUM DEIR-EL-BAHARI THE TOMBS OF THE KINGS EDFU KOM OMBOS PHILAE "PHARAOH'S BED" OLD CAIRO I THE PYRAMIDS Why do you come to Egypt? Do you come to gain a dream, or to regain lost dreams of old; to gild your life with the drowsy gold of romance, to lose a creeping sorrow, to forget that too many of your hours are sullen, grey, bereft? What do you wish of Egypt? The Sphinx will not ask you, will not care. The Pyramids, lifting page 2 / 128 their unnumbered stones to the clear and wonderful skies, have held, still hold, their secrets; but they do not seek for yours. The terrific temples, the hot, mysterious tombs, odorous of the dead desires of men, crouching in and under the immeasurable sands, will muck you with their brooding silence, with their dim and sombre repose. The brown children of the Nile, the toilers who sing their antique songs by the shadoof and the sakieh, the dragomans, the smiling goblin merchants, the Bedouins who lead your camel into the pale recesses of the dunes--these will not trouble themselves about your deep desires, your perhaps yearning hunger of the heart and the imagination. -

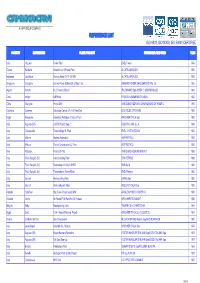

CAMUNA CAVI REFERENCE LIST 080818.Xlsx

A LAPP GROUP COMPANY REFERENCE LIST ISO 9001, ISO14000, ISO 50001 CERTIFIED COUNTRY DESTINATION PLANT / PROJECT PURCHASER / END USER YEAR Italy Vezzano Power Plant ENEL Trento 1994 Greece Keratsini Keratsini Unit 8 Power Plant ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Indonesia Java Barat Gunung Salak G.P.P. 55 MW ALCATEL/ANSALDO 1995 Singapore Singapore Senoko Power station Ext. of Gas Turb. SIEMENS/POWER GEN. (SENOKO) Pte. Ltd. 1995 Algeria Annata No.2 Furnace Ribuild ITALIMPIANTI SpA/SIDER C. SIDERURGIQUE 1996 China Ningbo NZP Plant FROESCHL/SIEMENS ERLAGEN 1996 China Shanghai Project D68 SINCO ENGINEERING/ CHINAYIZHENG CH. FIBER C 1996 Colombia Covenas Oleoducto Central S.A. Full Field Dev. BOUYGUES OFFSHORE 1996 Egypt Alexandria Alexandria Petroleum Crude Oil Furn. KIRCHNER ITALIA Spa 1996 Italy Augusta (SR) LSADO Project Step 2 ESSO ITALIANA S.p.A. 1996 Italy Civitavecchia Torrevaldaliga N. Plant ENEL- CIVITAVECCHIA 1996 Italy Milazzo Heaters Automation AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Milazzo Control Centralization LC-Finer AGIP PETROLI 1996 Italy Pallanza Project CF-762 SINCO ENGINEERING/ITALPET 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Interconnecting Plant ERG PETROLI 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Revamping Unit 200 A NHDS ISAB S.p.A. 1996 Italy Priolo Gargallo (Sr) Thermoelectric Power Plant ENEL-Palermo 1996 Italy Sarroch Hydrocracking Plant SARAS Spa 1996 Italy Sarroch Intrinsically-safe Plant HOECHST ITALIA Spa 1996 Pakistan Hub River Hub Power Project 4x323 MW ANSALDO/HUBCO POWER Co 1996 S.Arabia Yanbu Ibn Rushd/PTA Plant Hot Oil Furnace KIRCHNER/TECNIMONT 1996 Belgium Feluy Manufacturing Units TELEREX S.A. / PANTOCHIM 1997 Egypt Suez 10 H-1 Heater Revamp. Project KIRCHNER ITALIA S.p.A./ SUEZ OIL 1997 France St. -

Ahmose, Son of Ebana: the Expulsion of the Hyksos

Ahmose, son of Ebana: The Expulsion of the Hyksos Ahmose, son of Ebana, was an officer in the Egyptian army during the end of the 17th Dynasty to the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (16th century BCE). Originally from Elkab in Upper Egypt, he decided to become a soldier, like his father, Baba, who served under Seqenenre Tao II in the early campaigns against the Hyksos. Ahmose spent most of his military life serving aboard the king’s fleet - fighting at Avaris, at Sharuhen in Palestine, and in Nubia during the service of Ahmose I, and was often cited for his bravery in battle by the king. These accounts were left in a tomb that Ahmose, son of Ebana, identifies as his own at the end of the water—for he was captured on the city side-and he Crew Commander Ahmose son of crossed the water carrying him. When it was Abana, the justified; he says: I speak reported to the royal herald I was rewarded with T to you, all people. I let you know gold once more. Then Avaris was despoiled, and what favors came to me. I have been I brought spoil from there: one man, three rewarded with gold seven times in the sight women; total, four persons. His majesty gave of the whole land, with male and female them to me as slaves. slaves as well. I have been endowed with Then Sharahen was besieged for three years. very many fields. The name of the brave His majesty despoiled it and I brought spoil man is in that which he has done; it will not from it: two women and a hand. -

Embalming Caches

THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LO:'-JDON weIN 2PG ISSN 0307-5133 THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 94 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LONDON WCIN zPG CONTENTS TELL EL-AMARNA, 2007-8 Barry Kemp I THE PTOLEMAIC-RoMAN CEMETERY AT THE QUESNA ARCHAEOLOGICAL AREA Joanne Rowland I::\"TRODUCING TELL GABBARA: NEW EVIDENCE FOR EARLY DYNASTIC SETTLEMENT IN THE EASTERN DELTA Sabrina R. Rampersad . 95 THE COFFINS OF IYHAT AND TAIRY: A TALE OF Two CITIES Aidan Dodson . 1°7 .-\ GARLAND OF DETERMINATIVES Anthony J. Spalinger 139 A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSECTIVE ON EGYPTIAN COLONIALISM IN THE NEW KINGDOM . Michele R. Buzon 165 DIE DEMOTISCHEN STELEN AUS DER GEGEND YON HUSSANIYA/TELL NEBESHEH . Jan Moje a::\" THE PRESENCE OF DEER IN ANCIENT EGYPT: .-\NALYSIS OF THE OSTEOLOGICAL RECORD Chiori Kitagawa · 2°9 COLLECTING EGYPTIAN ANTIQUITIES IN THE YEAR 1838: REVEREND WILLIAM HODGE MILL Brian Muhs and .'-~D ROBERT CURZON, BARON ZOUCHE . Tashia Vorderstrasse · 223 THE NAOS OF 'BASTET, LADY OF THE SHRINE' FROM BUBASTIS Daniela Rosenow · 247 C::\"E BASE DE STATUE FRAGMENTAIRE DE SESOSTRIS pR PROVENANT DE DRA ABOU EL-NAGA David Lorand BRiEF COMMUNICATIONS THE SOUNDS OF rAIN IN EGYPTIAN, GREEK, COPTIC, AND ARABIC . Anthony Alcock. · 275 BDIERKUNGEN ZU ZWEI USURPIERTE SAULEN .-\1:5 DER ZEIT MERENPTAHS Y oshifumi Yasuoka . A ROCK ART PALIMPSEST: EVIDENCE OF THE RELHIVE AGES OF SOME EASTERN DESERT PETROGLYPHS . Tony Judd. 282 E. IB.-\L\lING CACHES. Marianne Eaton-Krauss. 288 _-\ '\"ERLAN' SCRIBE IN DEIR EL-BERSHA: ~ O:\IE DEMOTIC INSCRIPTIONS ON QC.-\RRY CEILINGS. -

Rousettus Aegyptiacus (Pteropodidae) in the Palaearctic: List of Records and Revision of the Distribution Range*

Vespertilio 15: 3–36, 2011 ISSN 1213-6123 Rousettus aegyptiacus (Pteropodidae) in the Palaearctic: list of records and revision of the distribution range* Petr BENDA1,2, Mounir ABI-SAID3, Tomáš Bartonička4, Raşit BILGIN5, Kaveh FAIZOLAHI6, Radek K. Lučan2, Haris NICOLAOU7, Antonín REITER8, Wael M. SHOHDI9, Marcel UHRIN10 & Ivan Horáček2 1 Department of Zoology, National Museum (Natural History), Václavské nám. 68, CZ–115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 7, CZ–128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic 3 Department of Biology, American University of Beirut, Riadh El Solh 1107, 2020 Beirut, Lebanon 4 Department of Botany and Zoology, Masaryk University, Kotlářská 2, CZ–611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 5 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Bogazici University, Bebek, TR–34342 Istanbul, Turkey 6 Mohitban Society, 2010 Mitra Alley, Shariati Street, Tehran, 1963816163, Iran 7 Forestry Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, Louki Akrita 24, Nicosia, Cyprus 8 South Moravian Museum in Znojmo, Přemyslovců 8, CZ–669 45 Znojmo, Czech Republic 9 Nature Conservation Egypt & Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt 10 Institute of Biology and Ecology, P. J. Šafárik University, Moyzesova 11, SK–040 01 Košice, Slovakia Abstract. The populations of Rousettus aegyptiacus inhabiting the Palaearctic part of the species range represent the only offshoot of the family Pteropodidae beyond tropics. In this contribution, we revised distribution status of the species in different parts of its Palaearctic range, re-examined the literature data and supplemented them with an extensive set of original records obtained in the field during the last two decades. -

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume

class93% BO~~BVR Library of ~delbertCollege V.3 of Western Rerane Unlvsrsity, Olsvoiand. 0. ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT ANCIENT RECORDS UNDER THE GENERAL EDITORSHIP OF WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA EDITED BY ROBERT FRANCIS HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT EDITED BY JAMES HENRY. BREARTED ANCIENT RECORDS OF PALESTINE, PH(EN1CIA AND SYRIA EDITED BY WILLIAM RAINEX HARPEB ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE PERSIAN CONQUEST. COLLECTED EDITED AND TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY JAMES HENRY BREASTED, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF EGYPTOLOGY AND ORIENTAL HISTORY IN TIIE UNIVBEWTY OF CHICAGO VOLUME I11 WHE NINETEENTH DYNASTY CHICAGO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1906 LONDON: LUZAC & CO. LEIPZIGI : OTTO HABRASSOWITZ Published May 1906 QLC.%, Composed and Printed By The University of Chicago Press Chicago. Illinois. U. S. A. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I THEDOCUMENTARY SOURCES OF EGYPTIANHISTORY . CHRONOLOGY........... CHRONOLOGICALTABLE ........ THEPALERMO STONE: THE FIRST TO THE FIFTH DYNASTIES I. Predynastic Kings ........ I1. First Dynasty ......... 111. Second Dynasty ........ IV. Third Dynasty ......... V . Fourth Dynasty ........ VI . Fifth Dynasty ......... THETHIRD DYNASTY ........ Reign of Snefru ...s . b ;- .... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Biography of Methen ........ THE FOURTHDYNASTY ........ Reign of Khufu ......... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Inventory Stela ......... Examples of Dedication Inscriptions by Sons . Reign of Khafre ......... Stela of Mertitydtes ........ Will of Prince Nekure. Son of King Khafre ... Testamentary Enactment of an Unknown Official. Establishing the Endowment of His Tomb by the Pyramid of Khafre ........ Reign of Menkure ......... Debhen's Inscription. Recounting King Menkure's Erec- tion of a Tomb for Him ....... TEE RFTHDYNASTY ......... Reign of Userkaf ......... v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Testamentary Enactment of Nekonekh .... I. -

TIE TEMPLE of ISIS, NEAR ASSUAN the COLOSSI of MEMNON Vol

Vol_ LI WASHINGTON, D. C., NOVEMBER 3, 1903 No 44 fact of the sound is established by many unim- Bahri, built by Queen Makare. The queen's peachable witnesses, and is variously described. brother, Thothmis II, who succeeded her, con- Septimius Severus repaired the statue, and it has ceived the gallant design of erasing all mention, since remained silent. The sound is now thought of his sister from the inscriptions of the temple, to•have been produced by the sudden heat of the and supplying his own name in their place. He rising sun expanding the stone, and Dairy Products in the Tree Tops causing numerous minute particles to IN the English dairy shops you may buy eggs, be cracked off. butter, milk, and bread. Well, in Jamaica, one Near the colossi are the ruins of the may gather a variety of all of these from the tree Ramesseum, a large temple built by tops. Rameses II. Some of the inscriptions The egg is a fruit called the ackie. It grows recording his victories over the Hit- on a large tree. A reddish, husk-like pod breaks tites are very interesting. The large open, and inside is a creamy yellow pulp which fallen colossus in the first court is a looks and tastes much like scrambled eggs. striking example of the. sculptural and Butter is supplied by the avacado, or alligator artistic skill of the ancient Egyptians. pear. Its meat is a yellowish pulp which spreads Passing the large temple of Seti I like butter, and tastes very like it, too. -

Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics

Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics Volume 6 Number 12 December 2014 ISSN 2006-9774 ABOUT JDAE The Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics (JDAE) (ISSN:2006-9774) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject such as The determinants of cassava productivity and price under the farmers’ collaboration with the emerging cassava processors, Economics of wetland rice production technology in the savannah region, Programming, efficiency and management of tobacco farms, review of the declining role of agriculture for economic diversity etc. The Journal welcomes the submission of manuscripts that meet the general criteria of significance and scientific excellence. Papers will be published shortly after acceptance. All articles published in JDAE are peer- reviewed. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/JDAE Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Prof. Diego Begalli Prof. Mammo Mu chie University of Verona Tshwane University of Technology, Via della Pieve, 70 - 37029 Pretoria, South Africa and San Pietro in Cariano (Verona) Aalborg University, Italy. Denmark. Prof. S. Mohan Dr. Morolong Bantu Indian Institute of Technology Madras University of Botswana, Centre for Continuing Dept. of Civil Engineering, Education IIT Madras, Chennai - 600 036, Department of Extra Mural and Public Education India. Private Bag UB 00707 Gaborone, Botswana. Dr. Munir Ahmad Dr. Siddhartha Sarkar Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (HQ) Faculty, Dinhata College, Sector G-5/1, Islamabad, 250 Pandapara Colony, Jalpaiguri 735101,West Pakistan. Bengal, Ind ia. Dr. Wirat Krasachat Dr. Bamire Adebayo Simeon King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang Department of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of 3 Moo 2, Chalongkrung Rd, Agriculture Ladkrabang, Bangkok 10520, Obafemi Awolowo University Thailand. -

Egypt Through the Stereoscope

oi.uchicago.edu i EGYPT THROUGH THE STEREOSCOPE A JOURNEY THROUGH THE LAND OF THE PHARAOHS CONDUCTED BY JAMES HENRY BREASTED, PH.D. Professor of Egyptology and Oriental History in the University of Chicago Director of Haskell Oriental Museum of the University of Chicago Director of the Egyptian Expedition of the University of Chicago UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD New York London Ottawa, Kansas San Francisco, California Toronto, Canada Bombay, India The publication of this volume was made possible through the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ORIental INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO I oi.uchicago.edu ii UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD ©1905 by UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved Assembly The Oriental Institute All stereographs copyrighted MAP SYSTEM Patented in the United States, August 21, 1900 Patented in Great Britain, March 22, 1900 Patented in France, March 26, 1900. S.G.D.G. Switzerland, Patent 21,211 Miscellaneous Publications of the Oriental Institute Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain and Felicia Whitcomb Series Editors’ Acknowledgments Stereoscopes scanned by Palinopsia Studio, Chicago, Illinois Distributed on the Internet from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Chicago, Illinois • The United States of America oi.uchicago.edu iii CONTENTS PAGE STANDPOINTS IN EGYPT . v MAPS AND PLANS . ix FOREWORD . xi INTRODUCTION . 1 THE STORY OF EGYPT . 3 THE ITINERARY . 21 iii oi.uchicago.edu iv oi.uchicago.edu v STANDPOINTS IN EGYPT POSITION 1 . Pompey’s Pillar, the sailors’ landmark, and modern Alexandria . 23 2 . Cairo, home of the Arabian Nights, greatest city in Africa . -

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume I

ANCIENT RECORDS UNDER THE GENERAL EDITORSHIP OF WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA EDITED BY ROBERT FRANC18 HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYFT EDITED BY JAMES HENRY BREASTED ANCIENT RECORDS OF PALESTINE, PH(ENIC1A AND SYRIA EDITED BY WILLIAM RAINEY HARPEB ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT HISTORICAL DOCU FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE PERSIAN CONQUEST, COLLECTED EDITED AND TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY JAMES HENRY BREASTED, PH.D. PROFESSOR OP EGYPTOLOGY AND ORIENTAL HISTORY IN THE UNIVEESITP OF CHICAGO VOLUME I THE FIRST TO THE SEVENTEENTH DYNASTIES CHICAGO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1906 LONDON : LUZAC & CO. LEIPZIO: OTTO HARRASSOWITZ COPYRIGFIT 1906, BY THE UNIVBRSITYOP CHICAGO Published February 1906 Compoaed and Printed By The University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois, U.S. A. THEDE VOLUMES ARE DEDICATED TO MARTIN A. RYERSON NORMAN W. HARRIS MARY H. WILMARTH PREFACE In no particular have modem historical studies made greater progress than in the reproduction and publication of documentary sources from which our knowledge of the most varied peoples and periods is drawn. In American history whole libraries of such sources have appeared or are promised. These are chiefly in English, although the other languages of Europe are of course often largely represented. The employment of such sources from the early epochs of the world's history involves either a knowledge of ancient languages on the part of the user, or a complete rendition of the documents into English. No attempt has ever been made to collect and present all the sources of Egyptian history in a modern language. A most laudable beginning in this direction, and one that has done great service, was the Records of the Past; but that series never attempted to be complete, and no amount of editing could make con- sistent with themselves the uncorrelated translations of the large number of contributors to that series. -

Print This Article

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections A DIFFERENT KIND OF DIGGING: SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY AS ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELDWORK PRACTICE Kees van der Spek ABSTRACT Using the Noble Tombs of the Theban necropolis as its starting point, but with obvious implications for other archaeological sites where there is a close relationship with resident local communities, this paper calls for archaeological research in Egypt to concern itself with the entire stratigraphy of a site, including the most recent sequence with its contemporary deposits. The paper argues for the inclusion of social and cultural anthropological observation in the research methodologies of archaeologists excavating in locations where nearby contemporary communities represent continuities in the stratigraphic sequence of the excavation concession. THE END OF STRATIGRAPHY community inhabits a fragile and unique World Heritage- listed archaeological landscape. Following a history of Between 2006 and 2010 the foothill hamlets of al-Qurna relocation initiatives that dates back to the mid-1940s,4 that village in the Theban necropolis on the Luxor west bank tension ultimately resulted in the demolition of the hamlets were demolished (Figures 1–2), and its resident community around the Noble Tombs and the destruction of the of Qurnawi was relocated to new settlements (Figure 3).1 contemporary social landscape of the Theban necropolis on The yellow, white, and blue walls of the mud-brick the Luxor west bank. houses—several of which were of historical value in their The demolitions wrought by the bulldozers between own right2 or had been decorated with hajj paintings 2006 and 2010 not only compromised the existing celebrating the pilgrimage to Mecca3—had disintegrated stratigraphy but also put an end to any further depositions into piles of rubble. -

A Few Fragments of Qurna History from Tarif

Caroline Simpson A few fragments of Qurna history from Tarif The Theban west bank, known as Qurna by those who live there, has been where archaeologists, antiquarians and collectors have lived and worked for centuries. They have excavated and recorded the details of tombs, temples – and occasion- ally houses – of people who lived many centuries earlier and whose lives they never knew, never experienced and never benefited from. Somehow the people and buildings of the living community were an irritant or unworthy of record. A shining exception is Zoltán Fábián whose work on the Bet Boghdady,1 the house of the Boghdady family, is to my knowledge the first in depth, professional study of a house and, to a certain extent, the associated lives of the people he was living and working amongst. I feel honoured to be asked to contribute to this birthday present with another fragment of knowledge of the living community of Qurna – albeit those who live off ‘the mountain’ in Tarif. Tarif is the area to the north of the road which runs along the Muslim cem- etery, which is itself north of Seti I temple, and the area of the Nobles Tombs and those of Dra Abu al-Naga which housed the hillside communities. Tarif is part of the administrative district of Qurna. It is a large area of flattish land with a number of huge three sided saff tombs (tombs with a row of entrances) and hundreds of other tombs of various sizes. Such tombs make excellent accommodation – free, good in all weathers, roomy, and with enough space for large or small family groups.