Egypt Through the Stereoscope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boatman's Quarterly Review

boatman’s quarterly review the journal of Grand Canyon River Guides, Inc. • voulme 31 number 3 fall 2018 Prez Blurb • Guide Profiles • Gilbert Hansen • Citizen Science Back of the Boat • GCRG News • Financial Fitness • Not For Sale Native Fish • Skunks • Bats • Bears • Mountain Lions boatman’s quarterly review Keeping the BQR Fresh: …is published more or less quarterly How You Can Help by and for GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES. GRAND CANYON RIVER GUIDES is a nonprofit organization dedicated to OOF! JUST LIKE MAGIC, the Boatman’s Quarterly Review appears in your mailbox, but as you can Protecting Grand Canyon imagine, putting together a 48-page newsletter is Setting the highest standards for the river profession P not quite as simple as that. As our keynote publication, Celebrating the unique spirit of the river community the quarterly journal celebrates (and educates about) Providing the best possible river experience the place we love and our river running heritage, but at the same time, it’s absolutely essential that we keep General Meetings are held each Spring and Fall. Our things fresh, modern, and forward-looking. That’s Board of Directors Meetings are generally held the first where you come in. Yes, you!! Wednesday of each month. All innocent bystanders are It is abundantly clear that our vibrant river urged to attend. Call for details. community is our biggest asset and a huge resource STAFF to tap. We therefore strongly encourage you to submit Executive Director LYNN HAMILTON something for the BQR, whether it is a story, an opinion Board of Directors piece, photography, poetry, artwork…whatever President AMITY COLLINS floats your boat, so to speak. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents 1 The Archaeology of Medieval Islamic Frontiers: An Introduction A. Asa Eger 3 Part I. The Western Frontiers: The Maghrib and The Mediterranean Sea 2 Ibāḍī Boundaries and Defense in the Jabal Nafūsa (Libya) Anthony J. Lauricella 31 3 Guarding a Well- Ordered Space on a Mediterranean Island Renata Holod and Tarek Kahlaoui 47 4 Conceptualizing the Islamic- Byzantine Maritime Frontier Ian Randall 80 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Part II. The SouthernNOT FOR Frontiers: DISTRIBUTION Egypt and Nubia 5 Monetization across the Nubian Border: A Hypothetical Model Giovanni R. Ruffini 105 6 The Land of Ṭarī’ and Some New Thoughts on Its Location Jana Eger 119 Part III. The Eastern Frontiers: The Caucasus and Central Asia 7 Overlapping Social and Political Boundaries: Borders of the Sasanian Empire and the Muslim Caliphate in the Caucasus Karim Alizadeh 139 8 Buddhism on the Shores of the Black Sea: The North Caucasus Frontier between the Muslims, Byzantines, and Khazars Tasha Vorderstrasse 168 9 Making Worlds at the Edge of Everywhere: Politics of Place in Medieval Armenia Kathryn J. Franklin 195 About the Authors 225 Index 229 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION vi Contents 1 In the last decade, archaeologists have increasingly The Archaeology of focused their attention on the frontiers of the Islamic Medieval Islamic Frontiers world, partly as a response to the political conflicts in central Middle Eastern lands. In response to this trend, An Introduction a session on “Islamic Frontiers and Borders in the Near East and Mediterranean” was held at the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) Annual Meet- A. Asa Eger ings, from 2011 through 2013. -

The Indian Ocean Trade and the Roman State

The Indian Ocean Trade and the Roman State This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Research Ancient History at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Troy Wilkinson 1500107 Word Count: c.33, 000 Footnotes: 7,724 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ............T. Wilkinson ......................................................... (candidate) Date .................10/11/2020....................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................T. Wilkinson ................................................... (candidate) Date ......................10/11/2020.................................................. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ......................T. Wilkinson ............................................... (candidate) Date ............................10/11/2020............................................ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to -

“Benevolent Supremacy”: Biblical Epic Films, Suez, and the Cultural Politics of U.S

“Benevolent Supremacy”: Biblical Epic Films, Suez, and the Cultural Politics of U.S. P ower Melani McAlister When The Ten Commandments opened in 1956, the critical consensus was that DeMille had created a middle-brow, melo- dramatic, and highly suspect account of the biblical story of Moses. Newsweek described the film as forced and “heavy- handed,” while the re v i ewer for Ti m e called The Te n Commandments – speaking in the epic terms of the film itself — “perhaps the most vulgar movie ever made.”1 Despite the critical consensus against it, however, DeMille’s version of the exodus story was a remarkable box-office success. It would become the best known and most popular of the cycle of reli- gious epics that swept the United States in the 1950s. For six of the twelve years from 1950 to 1962, a religious historical epic was the year’s number-one box office moneymaker.2 The Ten Commandments and other films like it–Ben Hur, The Robe, Quo Vadis–were offered up as pious activity. Ads for The Ten Commandments carried endorsements from a Baptist minister, a Rabbi, and the Cardinal of New York. And at luncheon in Manhattan just after the opening, DeMille told the guests: “I came here and ask you to use this picture, as I hope and pray that God himself will use it, for the good of the world...”3 But the Jewish and/or Christian plots of these films were narrated in a distinctly contemporary dialect, as tales in Melani McAlister, Assistant Professor Department of American Studies, George Washington University,Washington, D.C., USA 194 Benevolent Supremacy which moral virtue barely triumphed over elaborately staged sexual temptation. -

Geodynamics and Geospatial Research CONFERENCE PAPERS

Geodynamics and Geospatial Research CONFERENCE PAPERS University of Latvia International ISBN 978-9934-18-352-2 Scientific 9 789934 183522 Conference th With support of: Latvijas Universitātes 76. starptautiskā zinātniskā konference Latvijas Universitātes Ģeodēzijas un Ģeoinformātikas institūts Valsts pētījumu programma RESPROD University of Latvia 76th International Scientific Conference Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformatics ĢEODINAMIKA UN ĢEOKOSMISKIE PĒTĪJUMI GEODYNAMICS AND GEOSPATIAL RESEARCH KONFERENCES zināTNISKIE RAKSTI CONFERENCE PAPERS Latvijas Universitāte, 2018 University of Latvia 76th International Scientific Conference. Geodynamics and Geospatial Research. Conference Papers. Riga, University of Latvia, 2018, 62 p. The conference “Geodynamics and Geospatial Research” organized by the Uni ver sity of Latvia Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformatics of the University of Latvia addresses a wide range of scientific studies and is focused on the interdisciplinarity, versatility and possibilities of research in this wider context in the future to reach more significant discoveries, including business applications and innovations in solutions for commercial enterprises. The research presented at the conference is at different stages of its development and presents the achievements and the intended future. The publication is intended for researchers, students and research social partners as a source of current information and an invitation to join and support these studies. Published according to the decision No 6 from May 25 2018 of the University of Latvia Scientific Council Editor in Chief: prof. Valdis Seglins Reviewers: Dr. R. Jäger, Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences Dr. B. Bayram, Yildiz Technical University Dr. A. Kluga, Riga Technical university Conference papers are published by support of University of Latvia and State Research program “Forest and Mineral resources studies and sustainable use – new products and Technologies” RESPROD no. -

A Sketch of the Geography and History of Egypt

A SKETCH OF THE GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF EGYPT EGYPT, situated in the northeastern corner of Africa, is a small country, if compared with the huge continent of which it forms a part; its size about equals that of the state of Maryland. And yet it has produced one of the greatest civilizations of the world. Egypt is the land on both sides of the lower part of the river Nile, from the town of Assuan (Syene) at the First Cataract (i.e. rapids) down to the Mediterranean Sea. Nature herself has divided the country into two different parts: the narrow stretches of fertile land adjoining the river from Assuan down to the region of modern Cairo--which we call "Upper Egypt" or the "Sa'id"- and the broad triangle, formed in the course of millennia from the silt deposited by the river where it flows into the Mediterranean. This we call "Lower Egypt" or the "Delta." In the course of history, a number of towns and cities have sprung up along the Upper Nile and its branches in the Delta. The two most impor- tant cities in antiquity were Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. The site of Memphis, not far south of modern Cairo, is largely covered by palm groves today. At Thebes the remains of the temples of Amon, named after the neighboring villages of Karnak and Luxor, are still imposing witnesses of bygone greatness and splendor. The only other sites I shall mention are those from which specimens in our collection have come. -

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications the Hyper-Style and the Double Dedications

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 28 | 2015 Varia Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications The Hyper-style and the Double Dedications Eleni Fassa Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2333 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2333 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2015 Number of pages: 133-153 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Eleni Fassa, « Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications », Kernos [Online], 28 | 2015, Online since 01 October 2017, connection on 21 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ kernos/2333 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2333 This text was automatically generated on 21 December 2020. Kernos Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications 1 Sarapis, Isis, and the Ptolemies in Private Dedications The Hyper-style and the Double Dedications Eleni Fassa An extended version of this paper forms part of my PhD dissertation, cited here as FASSA (2011). My warmest thanks to Sophia Aneziri for her always insightful comments. This paper has benefited much from the constructive criticism of the anonymous referees of Kernos. 1 In Ptolemaic Egypt, two types of private dedications evolved, relating rulers, subjects and gods, most frequently, Sarapis and Isis.1 They were formed in two ways: the offering was made either to Sarapis and Isis (dative) for the Ptolemaic kings (ὑπέρ +genitive) — hereafter, these will be called the hyper-formula dedications2 — or to Sarapis, Isis (dative) and the Ptolemaic kings (dative), the so-called ‘double dedications’. -

The History of Ancient Egypt “Passionate, Erudite, Living Legend Lecturers

“Pure intellectual stimulation that can be popped into Topic Subtopic the [audio or video player] anytime.” History Ancient History —Harvard Magazine The History of Ancient Egypt “Passionate, erudite, living legend lecturers. Academia’s best lecturers are being captured on tape.” —The Los Angeles Times The History “A serious force in American education.” —The Wall Street Journal of Ancient Egypt Course Guidebook Professor Bob Brier Long Island University Professor Bob Brier is an Egyptologist and Professor of Philosophy at the C. W. Post Campus of Long Island University. He is renowned for his insights into ancient Egypt. He hosts The Learning Channel’s popular Great Egyptians series, and his research was the subject of the National Geographic television special Mr. Mummy. A dynamic instructor, Professor Brier has received Long Island University’s David Newton Award for Teaching Excellence. THE GREAT COURSES® Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, VA 20151-2299 Guidebook USA Phone: 1-800-832-2412 www.thegreatcourses.com Cover Image: © Hemera/Thinkstock. Course No. 350 © 1999 The Teaching Company. PB350A PUBLISHED BY: THE GREAT COURSES Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfi elds Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 Phone: 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax: 703-378-3819 www.thegreatcourses.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 1999 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. -

Survey and Salvage Epigraphy of Rock-Cut Graffiti and Inscriptions in the Area of Aswan Report on the Season in Autumn 2012 and Spring 2013

Survey and Salvage Epigraphy of Rock-Cut Graffiti and Inscriptions in the Area of Aswan Report on the Season in Autumn 2012 and Spring 2013 by Linda Borrmann (German Archaeological Institute Cairo) 1) Introduction 2) The site of the Royal Stelae south of Aswan a. Setting b. Stelae c. Further inscriptions d. Preliminary results 3) Rock art in Wadi Berber on the West Bank of Aswan a. Setting b. Rock art c. Landscape and spatial recording 1) Introduction From October 23, 2012 until December 05, 2012 and from March 03, 2013 until March 07, 2013 work on surveying and salvage epigraphy on rock inscriptions and rock art in the Aswan area was continued in the framework of the joint project between the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and the Ministry of State for Antiquities (MSA).1 During this field season work on a group of New Kingdom royal stelae situated south of the town of Aswan (behind the workshop "Turquoise Joaillerie") and at a rock art site in Wadi Berber on the West Bank of Aswan was completed. 1 Members of the team were: Dr. Fathy Abu Zeid (head of the mission, MSA), Dr. Abd el Hakim Karrar (head of the mission, MSA), Prof. Dr. Stephan Seidlmayer (head of the mission, DAI Cairo), Linda Borrmann M.A. (field director, DAI Cairo), Adel Kelany (field director, MSA), Rebecca Döhl M.A. (sub-project “Rock Art in Wadi Berber”), Shazli Ali Abd el Azim, Alexander Juraschka, Anita Kriener M.A., Mahmoud Mamdouh Mokhtar, Ahmed Mohamed Hassan Mohamed, Heba Saad Harby, Elisabeth Wegner (members of the collaborative team), Mohamed Abdu Ali, Salah el Deen Ismael Abd el Raof, Yosra Khalf Allah el Zohry, Ahmed Mohamed Ahmed (trainees of the MSA). -

Chapter 4: Egypt, 3100 B.C

0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 66 CHAPTER Egypt 4 3100 B.C.–671 B.C. Tutankhamen’s gold mask ᭤ ᭡ Wooden Egyptian sandals 2600 B.C. 2300 B.C. 1786 B.C. 1550 B.C. 671 B.C. Old Kingdom Middle Kingdom Hyksos invade Ahmose founds Assyrians take established begins Egypt the New over Egypt Kingdom 66 UNIT 2 RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATIONS 0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 67 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • Why the Nile River was so important to the growth of at humanheritage.glencoe.com Egyptian civilization. and click on Chapter 4—Chapter • How Egyptian religious beliefs influenced the Old Kingdom. Overviews to preview this chapter. • What happened during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. • Why Egyptian civilization grew and then declined during the New Kingdom. • What the Egyptians contributed to other civilizations. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate shadoof Narmer Nile River pharaoh Ahmose Punt pyramids Thutmose III Thebes embalming Hatshepsut mummy Amenhotep IV legend hieroglyphic papyrus Why It’s Important The Egyptians settled in the Nile River val- ley of northeast Africa. They most likely borrowed ideas such as writing from the Sumerians. However, the Egyptian civiliza- tion lasted far longer than the city-states and empires of Mesopotamia. While the people of Mesopotamia fought among themselves, Egypt grew into a rich, powerful, and unified kingdom. The Egyptians built a civilization that lasted for more than 2,000 years and left a lasting influence on the world. -

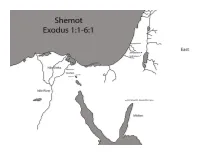

Shemot Map Updated.Pdf

Mapping the Portion In Torah Portion Shemot, we have a lot of traveling to do! You will need 3 colors to complete this map: red, blue and green. You can use whichever medium you wish: crayons, pencils or markers. Mapping can be done as you reach each verse in your portion, or as a separate activity. The goal of mapping is to familiarize yourself with the geography of the land, to visualize where important Biblical events happened and to bring Bible history to life! Genesis 47:27 Israelites living in Goshen Color the area around Goshen in BLUE, including Rameses and Pithom Exodus They built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for 1:11 Pharoah Exodus Every boy that is born you must throw into the 1:22 Nile Outline the Nile in RED Exodus But Moses fled from Pharaoh and went to live in 2:15 Midian Draw a path from Ramses to Midian in GREEN [Moses] led the flock to the far side of the desert Exodus and came to Horeb, the mountain of YHVH 3:1 (God) Draw a path to Mt. Sinai* in GREEN Exodus 4:18 Moses went back to Jethro Draw a path back to Midian in GREEN Exodus [Aaron] met Moses at the Mountain of YHVH 4:27 (God) Draw a path back to Mt. Sinai in GREEN Exodus 4:29 Met with Elders (in Egypt) Draw a path back to Rameses in GREEN Circle Jerusalem in RED. Draw a line in GREEN from the East to Jerusalem. You can start from Matthew Wise men from the East arrive in Jerusalem the edge of the page or at the word “East”- since we are not exactly sure where in they East they 2:1 looking for Yeshua (Jesus) came from! Matthew 2:8 Wise men travel to Bethlehem Circle Bethlehem in BLUE and draw a line in GREEN connecting Jerusalem to Bethlehem The map provided was created based on our best research.