The Egypt-Palestine/Israel Boundary: 1841-1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Great Sacrifices Born out of Great Love | Read John 3:16 and 15:13 History Is Filled with Stories of People Who Paid the Ultimate Price for Those They Loved

July 7 | Sunday Playlist: The Ones That Didn’t Make it Back Home Read John 15:9-17 08 | Mon – Great sacrifices born out of great love | Read John 3:16 and 15:13 History is filled with stories of people who paid the ultimate price for those they loved. Best- selling fiction has been written on this theme of making sacrifices so others could live. Jesus gave high honor to those who laid down their lives for others, calling it the greatest kind of love - love in action. Who would you die for and why? 09 | Tue – No, after you | Read 1 Corinthians 13:5 Self-sacrifice is the true measure of authentic love. It’s the reason why people donate kidneys, give blood or pass up a ‘golden’ career opportunity that would diminish family life. Each day you make choices, consciously or unconsciously, which reveal how much you love God and care about others. It takes maturity to put your self second and it also honors God. So who will you step aside for today so they can be first in line? 10 | Wed – Protecting the vulnerable | Read Numbers 26:59 / Exodus 2:1-10 Jochebed was a woman who knew the meaning of sacrifice. The king’s edict mandated that every male Hebrew baby was to be thrown into the Nile. Courageously, she kept her beautiful baby boy as long as she could and then obeyed the edict, putting him into the Nile River in a basket, trusting God to do what she could not. Her baby’s life was saved but he would not be known as her son. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Hayim Katsman Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE Hayim Katsman Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington [email protected] EDUCATION: • PhD., 2021 (expected) – University of Washington, Jackson School of International Studies. Dissertation title: “New Trends in Religious-nationalist politics in Israel/Palestine” Ph.D. Committee: Prof. Jim Wellman (chair), Prof. Joel Migdal, Prof. Liora Halperin, Prof. Christian Novetzke. • M.A., 2017 – Ben-Gurion University, Department of Politics and Government. Thesis subject: “Political Extremism in Israel: The case of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg and Religious-Zionism.” Advisors: Prof. Neve Gordon & Prof. Dani Filc. • B.A., 2014 – The Open University of Israel, Philosophy and Political Science. ACADEMIC TEACHING: 2019, Lecturer, JSIS 458: Israel: Politics and Society, University of Washington. 2019, Teaching assistant, HSTCMP 269: The Holocaust: History and Memory, University of Washington. 2014-2017, Teaching Assistant, Ben-Gurion University. Courses Taught: - Introduction to Political Philosophy - Israeli Politics - Introduction to International Relations (Israeli Air Force Academy) PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS Accepted: Hayim Katsman & Guy Ben-Porat, Israel: Religion and Political Parties. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Political Parties, Ed. Jeff Haynes. (Routledge, 2019, Forthcoming). Hayim Katsman, Reactions Towards Jewish Radicalism: Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg and Religious Zionism. In Jewish Radicalisms, Ed. Frank Jacob & Sebestian Kunze (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019, Forthcoming). Articles under review: “Radicalism and violence in Religious-Zionist thought? The Case of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg” BOOK REVIEWS Hayim Katsman, Review of Avi Sagi and Dov Schwartz, Religious Zionism and the Six-Day War: From Realism to Messianism; M. Hellinger et. al, Religious Zionism and the Settlement Project: Ideology, Politics, and Civil Disobedience. Israel studies review 34:2, pp. -

Yahoel As Sar Torah 105 Emblematic Representations of the Divine Mysteries

Orlov: Aural Apocalypticism / 4. Korrektur / Mohr Siebeck 08.06.2017 / Seite III Andrei A. Orlov Yahoel and Metatron Aural Apocalypticism and the Origins of Early Jewish Mysticism Mohr Siebeck Orlov: Aural Apocalypticism / 4. Korrektur / Mohr Siebeck 08.06.2017 / Seite 105 Yahoel as Sar Torah 105 emblematic representations of the divine mysteries. If it is indeed so, Yahoel’s role in controlling these entities puts him in a very special position as the dis- tinguished experts in secrets, who not only reveals the knowledge of esoteric realities but literally controls them by taming the Hayyot and the Leviathans through his power as the personification of the divine Name. Yahoel as Sar Torah In Jewish tradition, the Torah has often been viewed as the ultimate com- pendium of esoteric data, knowledge which is deeply concealed from the eyes of the uninitiated. In light of this, we should now draw our attention to another office of Yahoel which is closely related to his role as the revealer of ultimate secrets – his possible role as the Prince of the Torah or Sar Torah. The process of clarifying this obscure mission of Yahoel has special sig- nificance for the main task of this book, which attempts to demonstrate the formative influences of the aural ideology found in the Apocalypse of Abraham on the theophanic molds of certain early Jewish mystical accounts. In the past, scholars who wanted to demonstrate the conceptual gap between apocalyptic and early Jewish mystical accounts have often used Sar Torah sym- bolism to illustrate such discontinuity between the two religious phenomena. -

The God Who Delivers (Part 2)

The God Who Delivers (part 2) Review from Creation to Jacob’s family in Egypt? Our last study ended the book of Genesis with Joseph enjoying life as the Pharoah’s commanding officer. After forgiving his brothers for what they had done, Jacob and his entire clan moves to Egypt and this is where the book of Exodus begins. What turn of event occurs in the life of the Israelites in Egypt? Exodus 1:8-11 A generation passes and new powers come to be. A new pharaoh “whom Joseph meant nothing” became fearful the Israelite nation, becoming so fruitful and huge, would rebel against him. The Israelites became slaves to the Egyptians. The Pharoah comes up with what solution? 1:22 Kill every Hebrew boy that is born. The future deliverer is delivered. 2:1-10. A boy is spared, saved from a watery death through the means of an “ark”. Sound familiar? Moses is delivered to one day deliver God’s people out of Egypt, but for the time being, was being brought up in the Egyptian royal household. Moses becomes an enemy to Egypt. 2:11-15. Moses tries to do what is right, but has to flee Egypt for his life so he goes to Mdian. God has a message for Moses. Chapter 3. The Lord tells Moses he will be the one to deliver the Israelites out of slavery, but Moses immediately doubts. 3:11. God tells Moses who He is. 3:14-15. I am who I am. God gives Moses special abilities in order to convince the people. -

Aqaba Pledge: a Reconsideration of the 'Anṣār’S Subscription To

THE 'AQABA PLEDGE: A RECONSIDERATION OF THE 'ANṢĀR’S SUBSCRIPTION TO THE PLEDGE by MATTHEW LEE VANAUKER (Under the Direction of Kenneth Honerkamp) ABSTRACT The ‘Aqaba pledge was a pivotal moment for early Islamic history. Often, however, it is read and understood in the context of Muhammad’s life. Consequently, much remains unanswered concerning the other party to the pledge, viz. the ‘Anṣār. Traditionally, it has been understood that the ‘Anṣār subscribed to the pledge in the context of their ongoing intertribal wars and that out of a desire to bring an end to those wars, seeing Muhammad as the means for that, they accepted the terms of the pledge. This paper expands on this traditional understanding. It begins by expanding on the traditionally understood sociopolitical context that surrounded the ‘Anṣār on the eve of the pledge, looking closely at the Perso-Byzantine war in the early seventh century. It then points to a hitherto unidentified cause that forced the ‘Anṣār to desire reconciliation and to accept the terms of the pledge. INDEX WORDS: ‘Aqaba pledge, Jewish Messianism, The Sasanian Conquest of Jerusalem in 614, Byzantine, Late Antiquity, Early Islam, ‘Anṣār THE 'AQABA PLEDGE: A RECONSIDERATION OF THE 'ANṢĀR’S SUBSCRIPTION TO THE PLEDGE by MATTHEW LEE VANAUKER B.A., Syracuse University, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Matthew Lee VanAuker All Rights Reserved THE 'AQABA PLEDGE: A RECONSIDERATION OF THE 'ANṢĀR’S SUBSCRIPTION TO THE PLEDGE by MATTHEW LEE VANAUKER Major Professor: Kenneth Honerkamp Committee: Alan Godlas Carolyn Jones Medine Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my wife, my daughter, and my parents. -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism Among Arabs in Israel Author(S): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol

The Political Geography of Ethnic Protest: Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism among Arabs in Israel Author(s): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1997), pp. 91-110 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/623053 Accessed: 19/04/2010 02:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. -

Chapter 4: Egypt, 3100 B.C

0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 66 CHAPTER Egypt 4 3100 B.C.–671 B.C. Tutankhamen’s gold mask ᭤ ᭡ Wooden Egyptian sandals 2600 B.C. 2300 B.C. 1786 B.C. 1550 B.C. 671 B.C. Old Kingdom Middle Kingdom Hyksos invade Ahmose founds Assyrians take established begins Egypt the New over Egypt Kingdom 66 UNIT 2 RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATIONS 0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 67 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • Why the Nile River was so important to the growth of at humanheritage.glencoe.com Egyptian civilization. and click on Chapter 4—Chapter • How Egyptian religious beliefs influenced the Old Kingdom. Overviews to preview this chapter. • What happened during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. • Why Egyptian civilization grew and then declined during the New Kingdom. • What the Egyptians contributed to other civilizations. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate shadoof Narmer Nile River pharaoh Ahmose Punt pyramids Thutmose III Thebes embalming Hatshepsut mummy Amenhotep IV legend hieroglyphic papyrus Why It’s Important The Egyptians settled in the Nile River val- ley of northeast Africa. They most likely borrowed ideas such as writing from the Sumerians. However, the Egyptian civiliza- tion lasted far longer than the city-states and empires of Mesopotamia. While the people of Mesopotamia fought among themselves, Egypt grew into a rich, powerful, and unified kingdom. The Egyptians built a civilization that lasted for more than 2,000 years and left a lasting influence on the world. -

The Demarcation Line

No.7 “Remembrance and Citizenship” series THE DEMARCATION LINE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE General Secretariat for Administration DIRECTORATE OF MEMORY, HERITAGE AND ARCHIVES Musée de la Résistance Nationale - Champigny The demarcation line in Chalon. The line was marked out in a variety of ways, from sentry boxes… In compliance with the terms of the Franco-German Armistice Convention signed in Rethondes on 22 June 1940, Metropolitan France was divided up on 25 June to create two main zones on either side of an arbitrary abstract line that cut across départements, municipalities, fields and woods. The line was to undergo various modifications over time, dictated by the occupying power’s whims and requirements. Starting from the Spanish border near the municipality of Arnéguy in the département of Basses-Pyrénées (present-day Pyrénées-Atlantiques), the demarcation line continued via Mont-de-Marsan, Libourne, Confolens and Loches, making its way to the north of the département of Indre before turning east and crossing Vierzon, Saint-Amand- Montrond, Moulins, Charolles and Dole to end at the Swiss border near the municipality of Gex. The division created a German-occupied northern zone covering just over half the territory and a free zone to the south, commonly referred to as “zone nono” (for “non- occupied”), with Vichy as its “capital”. The Germans kept the entire Atlantic coast for themselves along with the main industrial regions. In addition, by enacting a whole series of measures designed to restrict movement of people, goods and postal traffic between the two zones, they provided themselves with a means of pressure they could exert at will. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

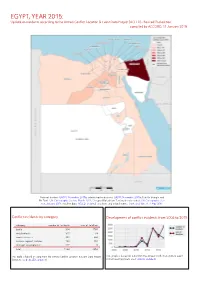

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha.