The Demarcation Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authors' Accepted Version: to Be Published in Antiquity Tormented

Authors’ Accepted Version: to be published in Antiquity Tormented Alderney: archaeological investigations of the Nazi labour and concentration camp of Sylt Sturdy Colls, C.¹, Kerti, J.¹ and Colls, K.¹ ¹ Centre of Archaeology, L214 Flaxman Building, Staffordshire University, College Road, Stoke-on- Trent, ST4 2DF. Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract Following the evacuation of Alderney, a network of labour and SS concentration camps were built on British soil to house foreign labourers. Despite government-led investigations in 1945, knowledge concerning the history and architecture of these camps remained limited. This article reports on the findings of forensic archaeological investigations which sought to accurately map Sylt labour and concentration camp the for the first time using non-invasive methods and 3D reconstructive techniques. It also demonstrates how these findings have provided the opportunity – alongside historical sources – to examine the relationships between architecture, the landscape and the experiences of those housed there. Introduction The Nazis constructed a network of over 44,000 (concentration, extermination, labour, Prisoner of War (PoW) and transit) camps across Europe, imprisoning and murdering individuals opposed to Nazi ideologies, and those considered racially inferior (Megargee & White 2018). Information about these sites varies in part due to Nazi endeavours to destroy the evidence of their crimes (Arad 1987: 26; Gilead et al. 2010: 14; Sturdy Colls 2015: 3). Public knowledge regarding the camps that were built on British soil in the Channel Islands is particularly limited, not least of all because they were partially demolished and remain “taboo” (Carr & Sturdy Colls 2016: 1). Sylt was one of several camps built on the island of Alderney (Figures 1 & 2). -

Mise En Page 1

THE LOIRE VALLEY, BIrthPLaCe OF the FINe GraIN SeSSILe Oak Pedonculate oak Sessile oak What IS FINe GraIN ? The fine grain oak corresponds to oak wood reaching a slow and regular growth with a ring width not above 2.5 mm. Only high silviculture management can grow the LOIre VaLLey, fine grain oakwood. The two main species in France are the sessile oak and BIrthPLaCe the pedunculate oak. They are very similar, but with very different chemical features. The sessile oak has great aromatic qualities and less tannin whereas the pedun - OF the FINe GraIN culate oak is very rich in tannins and less aromatic. SeSSILe Oak SESSILE OR PEDUNCULATE OAk ? Nothing can be more competitive than the sessile oak. Why ? Unlike the pedunculate oak, the sessile oak the world best quality wine is matured in fine grain barrels. thrives on poor soils and can bear the summer the specificity of these barrels gives alcoholic beverages, such as droughts. This characteristic slows down its growth in the world famous Cognac, their unique typical qualities. summer and contributes to the thinness of its annual this symbiotic union between content and container gives this rings, particularly in dense stand forests. precious nectar its final bouquet. In France, the fine grain oaks are sessile oaks. 1 a SPeCIFIC three CeNturIeS BIOGeOGraPhICaL OF uNCeaSING MaNaGeMeNt CONtext SINCe COLBert LOW RAINFALL The French state forests of the Loire valley have a long Colbert was the first the Loire valley is characterized by its low rainfall, parti - tradition of regular high woodland management which statesman with cularly in summer. -

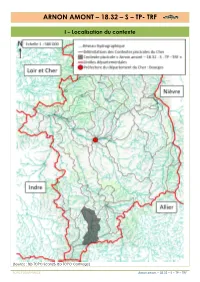

Arnon Amont – 18.32 – S – Tp- Trf

ARNON AMONT – 18.32 – S – TP- TRF I – Localisation du contexte (Source : BD TOPO Scan25, BD TOPO Carthage) R PDPG FDAAPPMA18 Arnon amont – 18.32 – S – TP – TRF II – Description générale *Cette carte n’a qu’une valeur indicative, et n’est en aucun cas une carte des linéaires réglementaires de cours d’eau. Se référer à la carte du lien de la DDT du Cher (http://cartelie.application.developpement- durable.gouv.fr/cartelie/voir.do?carte=conditionnalite&service=DDT_18) (Source : DDT 18). (Source : BD Carthage, BD SURFACE_EAU, BD ROE_Métropole_20140527) PDPG FDAAPPMA18 Arnon amont – 18.32 – S – TP – TRF SYNTHESE DESCRIPTION CONTEXTE L’Arnon prend sa source dans le département de la Creuse au lieu-dit « Le Petit Jurigny » (commune de Saint-Marien), puis s’écoule dans le département de l’Allier avant de se jeter dans le plan d’eau de la retenue de Sidiailles, pour enfin traverser le département du Cher et confluer avec la rivière Le Cher au niveau des commune de Vierzon et Saint-Hilaire-de-Court. Situé au sud du département, ce contexte piscicole représente un tronçon de la partie amont du cours d’eau compris entre l’aval du plan d’eau de Sidiailles et la confluence avec la rivière le Portefeuille. Dans ce contexte, l’Arnon s’écoule dans les régions naturelles de La Marche puis du Boischaut, dans un environnement agricole au relief assez marqué (Source : Chambre d’agriculture du Cher), et reçoit les débits de nombreux petits affluents (ru de l’étang de la Grange de Nohant, Rifoulet, Palonnière, ru des caves…). -

A Stimulating Heritage

DISTILLER OF SENSATIONS AMUS-EUM YOURSELVES! You’ve not seen cultural sites like these before! Keep tapping your foot... Blues, classical, rock, electro… festivals to A stimulating be consumed without moderation heritage Top 10 family activities An explosive mixture! TÉLÉCHARGEZ L’APPLICATION 04 06 CONT Frieze Amus-eum ENTS chronological YOURSELVES ! 12 15 In the Enjoy life in a château ! blessèd times of the abbeys 16 18 Map of our region A stimulating Destination Cognac heritage 20 On Cognac 23 24 Creativity Walks and recreation in the course of villages 26 30 Cultural Top 10 diversity family activities VISITS AND HERITAGE GUIDE VISITS AND HERITAGE 03 Frieze chronological MIDDLE AGES 1th century ANTIQUITY • Construction of the Château de First vines planted and creation of Bouteville around the year 1000 the first great highways • 1st mention of the town of Cognac (Via Agrippa, Chemin Boisné …) (Conniacum) in 1030 • Development of the salt trade LOWER CRETACEOUS along the Charente PERIOD 11th to 13th centuries -130 million years ago • Romanesque churches are built all • Dinosaurs at Angeac-Charente over the region 14th and 15th centuries • The Hundred Years War (1337-1453) – a disastrous period for the region, successively English and French NEOLITHIC PERIOD RENAISSANCE • Construction of several dolmens End of the 15th century in our region • Birth of François 1st in the Château de Cognac in 1494 King of France from 1515 to 1547 16th century • “Coup de Jarnac” - In 1547, during a duel, Guy de Chabot (Baron de Jarnac) slashed the calf of his adversary, the lord of La Châtaigneraie with a blow of his sword. -

Vallée De La Loire Et De L'allier Entre Cher Et Nièvre

Vallée de la Loire et de l’Allier entre Cher et Nièvre Directive Habitats, Faune, Flore Directive Oiseaux Numéro europé en : FR2600965 ; FR2610004 ; FR8310079 (partie Nièvre) Numéro régional : 10 Département : Cher, Nièvre Arrondissements : cf. tableau Communes : cf. tableau Surface : 16 126 hectares Le site Natura 2000 « Vallée de la Loire et de l’Allier entre Cher et Nièvre » inclut les deux rives de la Loire sur un linéaire d’environ 80 Km et les deux rives de l’Allier sur environ 20 kilomètres dans le département de la Nièvre et du Cher. Ce site appartient majoritairement au secteur dit de la « Loire moyenne » qui s’étend du Bec d’Allier à Angers, également nommé « Loire des îles ». Il regroupe les divers habitats naturels ligériens, véritables refuges pour la faune et la flore façonnés par la dynamique des deux cours d’eau, et constitue notamment une zone de reproduction, d'alimentation ou de passage pour un grand nombre d'espèces d’oiseaux nicheuses, migratrices ou hivernantes. Le patrimoine naturel d’intérêt européen Le lit mineur de la Loire et de l’Allier : La Loire et son principal affluent sont des cours d’eau puissants. Leur forte dynamique façonne une multitude d’habitats naturels possédant un grand intérêt écologique. Les grèves, bancs d’alluvions sableuses ou graveleuses, permettent le développement d’une végétation spécifique, adaptée à la sécheresse temporaire et à la submersion et constituent un lieu de vie et de reproduction important pour plusieurs espèces de libellules et certains oiseaux pour leur reproduction. La Sterne naine, la Sterne pierregarin et l’Oedicnème criard, nichent exclusivement sur les sols nus et graveleux des grèves ou des bancs d’alluvions formés au gré de ces cours d’eau. -

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenze H5N1 in Poultry in France

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Animal & Plant Health Agency Veterinary & Science Policy Advice Team - International Disease Monitoring Preliminary Outbreak Assessment Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 in poultry in France 26 November 2015 Ref: VITT/1200 H5N1 HPAI in France Disease Report France has reported an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza, H5N1 in backyard poultry (broilers and layer hens) in the Dordogne (OIE, 2015; see map). An increase in mortality was reported with 22 out of 32 birds dead and the others destroyed as a disease control measure. Samples taken on the 19th November confirmed HPAI. Other disease control measures have been implemented including 3km protection and 10km surveillance zones in line with Directive 2005/94/EC. This is an initial assessment and as such, there is still considerable uncertainty about the source of virus and where or when a mutation event occurred. However the French authorities have confirmed by sequence analysis that this is a European lineage virus (European Commission, 2015) and as such control measures are focussed on poultry. Situation Assessment The preliminary sequence of the strain indicates it is closely related to LPAI strains detected previously in Europe which are clearly distinguishable from contemporary strains associated with transglobal spread since 2003. H5N1 LPAI was last reported in France in 2009 in Calvados department in northern France in decoy ducks (ie tethered by hunters, and often in contact with wild birds). H5N1 LPAI viruses of the ‘classical’ European lineage have been isolated from both poultry and wild birds sporadically in Europe, but mutation to high pathogenicity of these strains is a rare event. -

Sur Les Traces Des Rois Dans La Vallée De La Loire

Tour Code LO8D 2018 Loire Valley Deluxe 8 days Its romantic castles, churches, and famous gardens make the Loire Valley a unique charming area, where harmony between nature and architecture will make for an unforgettable trip. The Kings of France chose this area to live and left their historical imprint. Your route will take you not only along the longest river of France with its wild sides, but also among the famous vineyards of Anjou, picturesque villages, and the valleys of the Indre and Cher. Day 1 Tours Day 5 Azay-le-Rideau – Chenonceaux Self – Guided Cycling Trip 59 km 8 days / 7 nights Departure from Tours, Capital of Touraine. You will leave the Indre Valley in order to Before beginning your cycling tour, do not follow the Cher Valley. Passing through Grade: forget to visit this beautiful city with its Montbazon, and Bléré, nice little towns. Partly on cycle paths and little side routes, gothic cathedral, and old quarters. Followed by the famous castle of always asphalted, between the valleys slight Chenonceau called « Château des climbs Dames ». Maybe behind a door or during Day 2 Tours – Montsoreau 65 km a walk in the magnificent gardens you will meet the ghosts of Catherine de Medicis Arrival: Fri, Sat, Sun 26.03. – 29.10.2018 You will leave the city along the riverside or Diane de Poitiers. of the Loire. A few kilometres further, you arrive at the famous gardens of Villandry Price per person Day 6 Chenonceaux - Amboise 18 km Euro Castle. From the little roads parallel to the Loire, you have a nice view of the wilder Today’s route will lead you to the royal With 2 participants sides of the Loire River. -

3B2 to Ps.Ps 1..5

1987D0361 — EN — 27.05.1988 — 002.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COMMISSION DECISION of 26 June 1987 recognizing certain parts of the territory of the French Republic as being officially swine-fever free (Only the French text is authentic) (87/361/EEC) (OJ L 194, 15.7.1987, p. 31) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Decision 88/17/EEC of 21 December 1987 L 9 13 13.1.1988 ►M2 Commission Decision 88/343/EEC of 26 May 1988 L 156 68 23.6.1988 1987D0361 — EN — 27.05.1988 — 002.001 — 2 ▼B COMMISSION DECISION of 26 June 1987 recognizing certain parts of the territory of the French Republic as being officially swine-fever free (Only the French text is authentic) (87/361/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Having regard to Council Directive 80/1095/EEC of 11 November 1980 laying down conditions designed to render and keep the territory of the Community free from classical swine fever (1), as lastamended by Decision 87/230/EEC (2), and in particular Article 7 (2) thereof, Having regard to Commission Decision 82/352/EEC of 10 May 1982 approving the plan for the accelerated eradication of classical swine fever presented by the French Republic (3), Whereas the development of the disease situation has led the French authorities, in conformity with their plan, to instigate measures which guarantee the protection and maintenance of the status of -

Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic

Rewriting the Nation: Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic By Celine L Maillard A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Douglas P Collins, Chair Maya A Smith Susan Gaylard Ana Fernandez Dobao Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of French and Italian Studies College of Arts and Sciences ©Copyright 2019 Céline L Maillard University of Washington Abstract Rewriting the Nation: Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic Celine L Maillard Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Douglas P Collins Department of French and Italian Studies This research investigates the rewriting of the nation in France during the Third Republic and the role played by primary schools in the process of identity formation. Le Tour de la France par deux enfants, a textbook written in 1877 by Augustine Fouillée, is our entry point to illustrate the strategies used in manufacturing French identity. We also analyze other texts: political speeches from the revolutionary era and from the Third Republic, as well as testimonies from both students and teachers written during the twentieth century. Bringing together close readings and research from various fields – history, linguistics, sociology, and philosophy – we use an interdisciplinary approach to shed light on language and national identity formation. Our findings underscore the connections between French primary education and national identity. Our analysis also contends that national identity in France during the Third Republic was an artificial construction and demonstrates how otherness was put in the service of populism. -

Château Tour Prignac

Château Tour Prignac An everlasting discovery The château, Western front Research and texts realised by Yann Chaigne, Art Historian hâteau Tour Prignac was given its name by current owners the Castel Cfamily, shortly after becoming part of the group. The name combines a reference to the towers which adorn the Château and to the vil- lage of Prignac-en-Médoc, close to Lesparre, in which it is situated. With 147 hectares of vines, Château Tour Prignac is one of the largest vineyards in France today. The estate was once known as La Tartuguière, a name derived from the term tortugue or tourtugue, an archaic rural word for tortoise. We can only assume that the name alluded to the presence of tortoises in nearby waters. A series of major projects was undertaken very early on to drain the land here, which like much of the Médoc Region, was fairly boggy. The Tartuguière fountain, however, which Abbé Baurein described in his “Variétés borde- loises”, as “noteworthy for the abundance and quality of its water”, continues to flow on the outskirts of this prestigious Château. The history and architecture of the estate give us many clues to the reasons behind its present appearance. There is no concrete evidence that the Romans were present in the Médoc, neither is there any physical trace of a mediaeval Châ- teau at Tartuguière; it is probable, however, that a house existed here, and that the groundwork was laid for a basic farming operation at the end of the 15th century, shortly after the Battle of Cas- tillon which ended the Hundred Years War. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Memorial Day 2015

Memorial Day 2015 Good morning and thank you for coming. It is an honor to see so many people here on a day like this. I would like to thank the students—the students who recited the Gettysburg address and Logan’s General orders so that we will never forget the sacrifice of the men and women who fought 151 years ago this year to keep us free in the civil war, and students who entertained us …. Today, I would like to thank all the veterans who have served us in all wars, and ask all those who have served, in war and in peace, to please raise their hands and be recognized. I want to pause today to recall one specific group of veterans, and one particular day in history, that day, 70 years ago on June 6 and a small beachhead in France at a place that few people at that time had ever heard of – a place called Normandy. This June marks the 70th anniversary of the greatest amphibious landing ever attempted, before or since, the landing at Normandy. Let me take you back to those days in World War 2. America had been in the war for only two and a half years—less than that really since it takes time to train men, deploy them and put them in to battle. It is hard to imagine today, but the war had not gone well at first for the Allies. Allied forces had been driven from Belgium, from Czechoslovakia, France had been overrun, Paris was run by Nazi soldiers, Italy was run by Mussolini-- a Nazi ally, 340,000 British soldiers had been forced to retreat from Europe back to Britain at Dunkirk.