AYALA-WALSH.Thesis.Oct. 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Global Visual Memory a Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs

The Global Visual Memory A Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs Het Mondiaal Visueel Geheugen Een studie naar de herkenning en interpretatie van iconische en historische foto’s (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 19 juni 2019 des middags te 2.30 uur door Rutger van der Hoeven geboren op 4 juni 1974 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. dr. J. Van Eijnatten Table of Contents Abstract 2 Preface 3 Introduction 5 Objectives 8 Visual History 9 Collective Memory 13 Photographs as vehicles of cultural memory 18 Dissertation structure 19 Chapter 1. History, Memory and Photography 21 1.1 Starting Points: Problems in Academic Literature on History, Memory and Photography 21 1.2 The Memory Function of Historical Photographs 28 1.3 Iconic Photographs 35 Chapter 2. The Global Visual Memory: An International Survey 50 2.1 Research Objectives 50 2.2 Selection 53 2.3 Survey Questions 57 2.4 The Photographs 59 Chapter 3. The Global Visual Memory Survey: A Quantitative Analysis 101 3.1 The Dataset 101 3.2 The Global Visual Memory: A Proven Reality 105 3.3 The Recognition of Iconic and Historical Photographs: General Conclusions 110 3.4 Conclusions About Age, Nationality, and Other Demographic Factors 119 3.5 Emotional Impact of Iconic and Historical Photographs 131 3.6 Rating the Importance of Iconic and Historical Photographs 140 3.7 Combined statistics 145 Chapter 4. -

Itinéraires, 2019-2 Et 3 | 2019 Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: the Case of Nicaragua 2

Itinéraires Littérature, textes, cultures 2019-2 et 3 | 2019 Corps masculins et nation : textes, images, représentations Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua Performances de genre en contextes révolutionnaires : le cas du Nicaragua Viria Delgadillo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6929 DOI: 10.4000/itineraires.6929 ISSN: 2427-920X Publisher Pléiade Electronic reference Viria Delgadillo, « Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua », Itinéraires [Online], 2019-2 et 3 | 2019, Online since 13 December 2019, connection on 15 December 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6929 ; DOI : 10.4000/itineraires.6929 This text was automatically generated on 15 December 2019. Itinéraires est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua 1 Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua Performances de genre en contextes révolutionnaires : le cas du Nicaragua Viria Delgadillo Introduction 1 Gender policies were at the heart of the 1980s Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional’s (FSLN) plans for social change. These policies were crucial to the legitimation of the Sandinista government, both domestically and abroad. In the existing literature on the Nicaraguan revolution, the issues of gender and legal reform as well as gender and revolutionary ideology have been dealt with at length. Molyneux’s (2001), Kampwirth’s (1998, 2006, 2013, 2015) and Montoya’s (2003) illuminating works on Sandinista law-making and gender ideology address how revolutionary ideology shapes legislation regarding women, LGBTQI individuals and the family. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pardos in Vallegrande : an exploration of the role of afromestizos in the foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6m01m9bd Author Weaver Olson, Nathan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pardos in Vallegrande: An Exploration of the Role of Afromestizos in the Foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Nathan Weaver Olson Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2010 Copyright Nathan Weaver Olson, 2010 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nathan Weaver Olson is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For Kimberly, who lived it. iv EPIGRAPH The descent beckons As the ascent beckoned. Memory is a kind of accomplishment, a sort of renewal even an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places inhabited by hordes heretofore unrealized … William Carlos Williams v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication …………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………... vi List of Charts ………………………………………………………………….. viii List of Maps …………………………………………………………………… ix Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. x Abstract ………………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction: Viedma and Vallegrande…………………………...……………. 1 Chapter 1: Representations of the Past ………………………………………… 10 Viedma‘s Report ………………………………………………………. 10 Vallegrande Responds …………………………………………………. 18 Pardos and Caballeros Pardos …………………………………………. 23 A Hegemonic Narrative ……………………………………………….. 33 Chapter 2: Vallegrande as Region and Frontier ………………………………. -

Che Guevara, Nostalgia, Photography, Felt History and Narrative Discourse in Ana Menéndez’S Loving Che Robert L

Hipertexto 11 Invierno 2010 pp. 103-116 Che Guevara, Nostalgia, Photography, Felt History and Narrative Discourse in Ana Menéndez’s Loving Che Robert L. Sims Virginia Commonwealth University Hipertexto At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality. Che Guevara More and more I've come to understand that when we mourn what a place used to be, we are also mourning what we used to be. Ana Menéndez any of the discussions and debates of the Cuban Revolution in Miami, M Havana and elsewhere converge, merge and diverge in the person and persona of Che Guevara. This process produces a mesmerizing mixture of myth, reality, and nonsense which we are far from unscrambling: “There's just this fascination people have with the man - which is not of the man, but of the photograph," says Ana Menéndez, author of ‘Loving Che’” (http://www.csmonitor.com/2004/0305/p13s02-algn.html). The photograph in question is Alberto Korda’s famous picture of Che Guevara taken on March 5, 1960 at a Cuban funeral service for victims of the La Coubre explosion. The photographic reality of Che soon transformed itself into an iconic image which traveled around the world. Che’s image has since undergone myriad changes and has become a pop culture, fashionista icon and capitalist commodity marketed and sold all over the world, including Cuba. Nostalgia and memory occupy the interstitial space between Che Guevara’s personal and revolutionary life and his now simulacralized iconicity: “Part of Guevara's appeal is that his revolutionary ideals no longer pose much of a threat in the post-cold-war world. -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

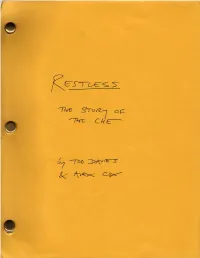

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Sabotage Du Navire Français La Coubre Le 4 Mars 1960 Nadine Lalande

Sabotage du navire français La Coubre le 4 mars 1960 Nadine Lalande Le sabotage du navire La Coubre dans la mémoire du peuple cubain. L’une des premières actions terroristes du Gouvernement des États-Unis contre Cuba eut un caractère monstrueux, le sabotage du navire français La Coubre le 4 mars 1960, à quai dans le port de la Havane. Le bateau avait chargé en Europe un lot important d’armements et d’équipements achetés à l’industrie nationale belge par le Gouvernement Révolutionnaire de Cuba, qui était déjà préoccupé par les actions agressives croissantes des États- Unis. Le chargement fut saboté par les agents de l’Agence Centrale d’Intelligence CIA au point d’embarquement, et les engins placés déclenchèrent une explosion ce jour-là à trois heures dix de l’après-midi alors que se déroulaient les opérations de déchargement. Aux premières heures de l’après-midi du 4 mars 1960, une détonation initiale se produisit et quelques minutes plus tard une deuxième qui causera le plus grand nombre de victimes, puisque à ce moment-là des dizaines de militaires et de travailleurs apportaient leur aide sur place aux victimes de la première explosion. Le navire la Coubre ainsi que le quai alentour étaient remplis de travailleurs portuaires, des soldats rebelles, de membres de la Police Nationale Révolutionnaire, de pompiers et du personnel de secours qui, sans se soucier du danger avaient accouru sur le lieu du désastre pour aider les victimes et pour prévenir les accidents. Le Commandant en Chef Fidel Castro Ruz, et d’autres dirigeants de la Révolution Cubaine firent acte de présence sur le lieu des faits. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Radical Chic? Yes We Are!

Radical Chic? Yes We Are! Johan Frederik Hartle 23 March 2012 Ever since Tom Wolfe in a classical 1970 essay coined the term "radical chic", upper-class flirtation with radical causes has been ridiculed. But by separating aesthetics from politics Wolfe was actually more reactionary than the people he criticized, writes Johan Frederik Hartle. Even the most practical revolutionaries will be found to have manifested their ideas in the aesthetic sphere. Kenneth Burke, 1936 Newness and the aesthetico-political A discussion of “radical chic” – a term used to denounce criticism and radical thought as something merely fashionable – is, to some extent, a discussion of the new. And while the merely fashionable is, in spite of its pretensions to be innovative and new, still conformist and predictable, being radical is the (sometimes tragic) attempt to differ. Such attempts to differ from prevailing (complacent, bourgeois) agreements are strongly dependent on the jargon of novelty. Therefore we find overlapping dimensions of the aesthetic and the political in the concept of the new. The new itself, a key concept of aesthetic modernity, however, has not always been fashionable. And the category of the new is of course nothing new itself. The new fills archives, whole libraries – and that is, somehow, a paradox in itself. Generations of modernist aestheticians were dealing with the question: why is there aesthetic innovation at all, and how is it possible? With the post-historical exhaustion of history the rejection of the new was cause for a certain satisfaction. Boris Groys argues that: the discourse on the impossibility of the new in art has become especially widespread and influential. -

Che 1Ère Partie: L'argentin 2E Partie: Guerilla

Fiche pédagogique Che 1ère partie: L'Argentin 2e partie: Guerilla Sortie prévue en salles 7 janvier 2009 (1ère partie) 28 janvier 2009 (2ème partie) Film long métrage de fiction, en deux parties, USA/France/ Espagne, 2008 Résumé l'éducation va de pair avec l'indépendance. Les Américains Réalisation : 1ère partie: L'Argentin envoyés en renfort pour soutenir Steven Soderbergh ("Traffic", l'armée cubaine sont impressionnés "Solaris", "Ocean's eleven"…) Comme le sous-titre l'indique, Le par l'organisation des docteur Ernesto Guevara est né en révolutionnaires : dans leur camp, Interprètes : Argentine en 1928. Bien qu'il se soit une école, une infirmerie, un hôpital, Benicio Del Toro (le Che), très jeune impliqué dans différents et même une centrale électrique. Demiàn Bichir (Fidel Castro), mouvements politiques (au Pérou, Toute cette première partie est Rodrigo Santoro (Raùl Castro), en Colombie, en Bolivie ou au rythmée par des extraits en noir et Julia Ormond (Lisa Howard), Guatemala, qu'il traverse à blanc de la visite du Che à New York Catalina Santino Moreno l'occasion de deux voyages latino- en 1964, de la rue (où il est traité (Aleida March), Joachim de américains de plusieurs mois; ce que d'assassin), à l'ONU, où il condamne Almeida (René Barrientos), développait le film "Carnets de l'oppression des peuples latino- Carlos Bardem (Moisés voyage" (2004) de Walter Salles), le américains ("Les 200 millions de Guevara), Marc-André Grondin film ne remonte pas plus tôt que latino-américains qui crèvent de faim (Régis Debray)... 1955. Cette année-là, à Mexico où il se tuent à la tâche pour produire des s'est exilé, Raùl Castro invite son biens pour l'économie des Etats- Scénario et dialogues : ami Guevara, qu'il avait rencontré au Unis") et où il essaie de retourner les Peter Buchman Guatemala, et lui présente son frère, valeurs admises ("Cuba est libre, les Fidel, exilé lui aussi, suite à Etats-Unis sont une prison") : le Production : Steven l'amnistie des prisonniers cubains de représentant des Etats-Unis n'est Soderbergh, Laura Bickford… 1955. -

Download Download

316.74:77 Rewriting Revolutionary Myths: Photography in Castro’s Cuba and Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper#6 Louisa Söllner LMU Munich Abstract: Photography was a key medium for creating, INTRODUCTION spreading, and cementing myths about the Cuban Revolution and its leaders. In the first part of this essay, In her novel Days of Awe (2001), Cuban-American I’ll explore several iconic images as well as responses to novelist Achy Obejas reproduces the following story these pictures, all parts of a Cuban “cross-national about Fidel Castro‟s victory speech on the 8th of memory discourse” (cf. Quiroga, 2005). Walter Benjamin’s media philosophy can help in developing January 1959: “On both sides of the Straits of Florida insights about the functioning of these photographs. In there‟s a story about Fidel‟s first victory speech in the second part of the paper, I turn to Tania Bruguera’s Havana. Sometime shortly after he began, a white dove piece Tatlin’s Whisper#6 (staged at the 10th Havana perched on his left shoulder, leaving everyone Biennial in 2009), which radically rewrites the poetics of breathless. This is Fidel‟s voodoo: He does the the images and aspires to create a sense of participation impossible. He gets that bird to pose with him, and direct involvement. whether through strategy or sorcery it doesn‟t matter. In one case, it’s divine intervention; in the other, a Keywords: Photography, Memory Mediation, Diaspora, ” Performance Art, Walter Benjamin stroke of theatrical genius; in both, he wins. (Obejas, 2001, p. 127) Obejas‟s novel reiterates and simultaneously rewrites a myth about Castro that has entered the collective memory of revolutionary Cuba and its 59 diaspora. -

De Ernesto, El “Che” Guevara: Cuatro Miradas Biográficas Y Una Novela*

Literatura y Lingüística N° 36 ISSN 0716 - 5811 / pp. 121 - 137 La(s) vida(s) de Ernesto, el “Che” Guevara: cuatro miradas biográficas y una novela* Gilda Waldman M.** Resumen La escritura biográfica, como género, alberga en su interior una gran diversidad de métodos, enfoques, miradas y modelos que comparten un rasgo central: se trata de textos interpre- tativos, pues ningún pasado individual se puede reconstruir fielmente. En este sentido, cabe referirse a algunas de las más importantes biografías existentes sobre el Che Guevara, como La vida en rojo, de Jorge G. Castañeda, (Alfaguara 1997); Che Ernesto Guevara. Una leyenda de nuestro siglo, de Pierre Kalfon (Plaza y Janés, 1997); Che Guevara. Una vida revo- lucionaria, de John Lee Anderson (Anagrama, 2006) y Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, de Paco Ignacio Taibo II (Planeta, 1996). Por otro lado, en la vida del Che, hay silencios oscuros que las biografías no cubren, salvo de manera muy superficial. Algunos de estos vacíos son retomados por la literatura, por ejemplo, a través de la novela de Abel Posse, Los Cuadernos de Praga. Palabras clave: Che Guevara, biografías, interpretación, literatura. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Lives. Four Biographies and one Novel Abstract The biographical writing, as a genre, shelters inside a wide diversity of methods, approaches, points of view and models that share a central trait: it is an interpretative text, since no individual past can be faithfully reconstructed. In this sense, it is worth referring to some of the most diverse and important biographies written about Che Guervara, (Jorge G. Castañeda: La vida en rojo, Alfaguara 1997; Pierre Kalfon: Che Ernesto Guevara.