Copyright by Crystal Marie Kurzen 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Gabriella Gutiérrez Y Muhs

September 2014 CURRICULUM VITAE Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs Department of Modern Languages Seattle University 901 12th Avenue Seattle, Washington 98122-4460 (206) 296-6393 [email protected] Education Ph.D. 2000 Stanford University (Spanish. Primary Field: Chicana/o Literature. Secondary Fields: Contemporary Peninsular and Latin American Studies. M.A. 1992 Stanford University (Spanish, Latin American and Peninsular Studies) Additional Studies University of California at Santa Cruz: Teacher Credential Program (Bilingual, Primary and Secondary, Clear credentials, Spanish and French.) Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. Rotary International Graduate Studies Scholarship, Spain. Colegio de México, Mexico City. Masters Degree Work. Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. Portuguese Language and Culture Studies Program; Diploma. Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA. B.A. in French & B.A. in Spanish. Minors: Sociology, Anthropology. Emphasis: Latin American Studies. Credentials Secondary Single Subject, Clear, in Foreign Languages (Spanish & French). Multiple Subject, Clear, Bilingual. University of California, Santa Cruz. Community College Teaching and Administrative Credential. Academic Employment Professor: Seattle University, March 2014-Present. Associate Professor: Seattle University, March, 2006-Present. Assistant Professor: Seattle University, Seattle, Washington. Fall 20002006. Teach culture, civilization, language, literature, and Women and Gender Studies courses. University Administrative Experience and Selected Committee Service 2014 – 2015 Co-Chair with Susan Rankin, Rankin & Associates, (experts in assessing the learning and working climates on college campuses,) of Climate Study Working Group, a result of the Diversity Task Force, 2013-2014. 2012-Present Co-Director Patricia Wismer Center for Gender, Justice, & Diversity. 2009 – 2013 University Rank and Tenure Committee Member, appointed by Academic Assembly, Arts and Sciences. Co-chaired the committee 2012-2013. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ARIZONA PRESS FALL 2017 the University of Arizona Press Is the Premier Publisher of Academic, Regional, and Literary Works in the State of Arizona

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS FALL 2017 The University of Arizona Press is the premier publisher of academic, regional, and literary works in the state of Arizona. We disseminate ideas and knowledge of lasting value that enrich understanding, inspire curiosity, and enlighten readers. We advance the University of Arizona’s mission by connecting scholarship and creative expression to readers worldwide. THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS CONTENTS ANTHROPOLOGY, 20, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 ARCHAEOLOGY, 28, 29, 30 BORDER STUDIES, 25 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, 26, 27, 31 HISTORY, 13, 16, 18, 19, 21, 24 INDIGENOUS STUDIES, 7, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27 LATINO STUDIES, 4–5, 6, 10–11, 12, 13, 14, 15 LITERATURE, 4–5 NATURE, 8–9 POETRY, 6, 7 SPACE SCIENCE, 32 TRAVEL ESSAYS, 2–3 CENTURY COLLECTION, 33 RECENTLY PUBLISHED, 34–36 SELECTED BEST SELLERS, 37–40 SALES INFORMATION, INSIDE BACK COVER CATALOG DESIGN BY LEIGH MCDONALD COVER PHOTOS COURTESY OF BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT/BOB WICK [FRONT] AND KEVIN DOOLEY [INSIDE] CUBA, HOT AND COLD TOM MILLER A rare and timely glimpse of life in Cuba from an expert on the captivating island nation Cuba—mysterious, intoxicating, captivating. Whether you’re planning to go or have just returned, Cuba, Hot and Cold is essential for your bookshelf. With a keen eye and dry wit, author Tom Miller takes readers on an intimate journey from Havana to the places you seldom find in guidebooks. A brilliant raconteur and expert on Cuba, Miller is full of enthralling behind-the-scenes stories. -

Pipes Adsorba Pipes Alba Pipes

Prices correct at time of printing 26/09/2018 SPECIAL OFFERS - Pipes Black Swan 46 Rattrays Pipe £109.99 Chacom Robusto Brown Sandblast 190 Pipe (CH009) £85.99 Davidoff 9mm Discovery Malawi Pipe (DAV03) £269.00 Hardcastle Argyle 101 Fishtail Pipe (H0049) £34.99 Hardcastle Briar Root 103 Checkerboard Fishtail Straight Pipe (H0025) £41.49 Hardcastle Camden 102 Smooth Fishtail Pipe (H0046) £52.99 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Apple Bent Pipe (LZ10) £220.00 Lorenzetti Italy Smooth Light Brown Unique Semi Bent Pipe (LZ08) £220.00 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1055) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 003 Fishtail Pipe (G1065) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 069 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1052) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent 408 Fishtail Pipe (G1066) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1051) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent X220 Fishtail Pipe (G1067) £69.99 Peterson 2017 Christmas Rustic Bent XL90 9mm Filter Fishtail Pipe (G1059) £69.99 Peterson Aran Smooth Pipe - 003 (G1034) £61.99 Peterson Around the World USA X105 Silver Mounted Pipe £79.99 Peterson Donegal Rocky Pipe - 003 (G1172) £65.99 Peterson Kinsale Curved Pipe XL15 (Squire) £83.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 120 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 305 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 338 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - 408 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe - B10 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 106 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - 606 £78.99 Peterson Limited Edition St Patricks Day 2018 Pipe with 9mm filter - X220 £78.99 Peterson Liscannor Bent Pipe - X220 £43.99 Peterson Standard System Rustic 313 Pipe (SR005) £72.99 Peterson Standard System Smooth 302 Pipe (G1255) £72.99 Rattrays Limited Edition Turmeaus 1817 Green Pipe No. -

NH Convenient Database

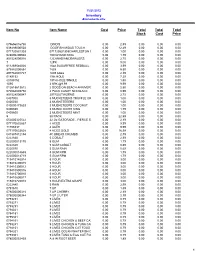

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

La Bloga “The Book of Want”

.comment-link {margin-left:.6em;} Report Abuse Next Blog» La Bloga Chicana, Chicano, Latina, Latino, & more. Literature, Writers, Children's Literature, News, Views & Reviews. About La Bloga's Blogueras & Blogueros "Best Blog 2006" MONDAY, FEBRUARY 6 award from L.A.'s Tu “The Book of Want” at the UCLA Chicano Studies Ciudad magazine Research Center Library, February 9th, 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. "Taking With Me The Land:" Xicana Nebraska ... A Mestiza mans The Chilean Winter. Children’s Lit ... Bits & Pieces On A Winter Friday Chicanonautica: Ocotillo Dreams, Arizona Dystopia 2012 Pura Belpré Award Winners Review: Clybourne Park. On-Line Floricanto Con Tinta Annual Pachanga at AWP Conference: This ... Con Tinta Annual Pachanga: Honoring Pat Mora Guest Columnist: Sonia Gutiérrez I Ask(ed) a Mexican y respondió I am delighted to announce that I will be reading from my novel, The Book la bloga. of Want (University of Arizona Press), at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. The reading will conclude with a Q&A and a book signing. DATE: Thursday, February 9 TIME: 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. WHERE: UCLA Campus, 144 Haines Hall CONTACT: Lizette Guerra, Archivist and Librarian, (310) 206-6052 E-MAIL: [email protected] Aaron A. Abeyta This is a homecoming, of sorts, because I attended law school at UCLA Mario Acevedo (where I met my brilliant and beautiful wife). Also, our son, Ben, is now a Marta Acosta UCLA junior majoring in anthropology. I hope to see many La Bloga Oscar "Zeta" Acosta readers in attendance! Alma Flor Ada Praise for The Book of Want: Daniel Alarcón Francisco X. -

Download the Forecast Channel for the Wii and Keep the System Online, the Weather During the Game Will Reflect That of the Weather in Your Town Or City (Ex

Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None Unlockables Alternative Endings Depending on whether you save certain people during the course of the game, you'll receive one of 4 different endings. Unlockable How to Unlock Best Ending (Narracott, Get to Lombard before he dies, then attack Lombard and Claythorne murderer to save Claythorne. survive) Poor Ending (Narracott and Reach Lombard before he dies, and do not attack Lombard survive) the murderer. Reasonable Ending (Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, then attack and Claythorne survive) murderer to save Claythorne. Worst Ending (Only Narracott Fail to reach Lombard before he dies, and do not survives) attack the murderer. Alien Syndrome Unlockables Unlock Extra Difficulties In order to unlock the other two game difficulties, Hard and Expert, you must beat the game on the previous difficulty. Unlockable How to Unlock Unlock Expert Difficulty Beat the game on Hard Difficulty. Unlock Hard Difficulty Beat the game on Normal Difficulty. Animal Crossing: City Folk Unlockables Bank unlockables Deposit a certain amount of bells into bank. Unlockable How to Unlock Box of Tissues Deposit 100,000 bells into the bank. Gold Card Reach "VIP" status. Shopping Card Deposit 10,000 bells into the bank. Piggy Bank Deposit 10,000,000 Bells ------------------------------- Birthday cake Unlockable How to Unlock Birthday Cake Talk to your neighbors on your birthday ------------------------------- Harvest Set To get a furniture item from the Harvest Set, You must talk to Tortimer after 3pm on Harvest Day. He will give you a Fork and Knife pair, telling you that the 'Special Guest' hasn't shown up yet. -

JUNE 30, 1900. ICT&Jvsbsi CENTS

DS PORTLAND PRESS. S PRICK THREE ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. 39. PORTLAND, MAINE, SATURDAY MORNING, JUNE 30, 1900._ICT&jVSBSI CENTS. down the steep Incline of Mission hill un- KJCW ADVIHTlIMBm PRESIDENT OPTIMISTIC. der perfect control, as several pn*«-nger> Tklaki Ik. Tro.kl. la Cklu la All were taken on a short distance from the top. Probably by the breaking of a link "Q of the chain which engage* the winding Washington, Jane The President and controls the the car for bla Canton ASHORE. post brakes, le OREGON FROM SEYMOUR. quitting Washington gained headway rapidly and In a moment BIG CRT home full of oonndenoe that the tonight, It was moving at a frightful rate toward situation In China has improved though the vladuat under the railroad bridge. It it le fair to say that all the members of passed this In safety but at a turn In the his ofllolal family do not agree with him track the car left the rattled across in that oonoluskra. Indead the day's rails, III PRICES. the pavements, mounted tho ourbstoi • news limited though It was to a single and striking the market ploughed away Extraordinary trade* are cablegram from Admiral Kerapff and the 800 feet of the When the of lnetruotlons to Ueneral square bnlldlng. offered for One Week preparation America’s Most Famous Only. British Admiral Tells of Adven- oar stopped It was completely burled n set calculated to Battleship Story Chaffee, out nothing Russet button the market and tho motorman was vainly Children’* goat, strengthen the hope* of the friends of the tugging at the brake. -

La Bloga: William A. Nericcio Holds Court at UCLA's Chicano Studies Research Center to Rapt Crowd

La Bloga: William A. Nericcio holds court at UCLA’s Chicano Studies R... http://labloga.blogspot.com/2013/11/william-nericcio-holds-court-at-ucla... Las Blogueras Los Blogueros Click to email a writer. Denver CO • Pasadena CA • The San Fernando Valley CA • Eagle Rock CA • Lincoln NE • Glendale AZ • Santa Barbara CA • Lincoln Heights CA • Kansas City MO La Bloga Archive Monday, November 25, 2013 La Bloga Links ▼ 2013 (323) - Authors ▼ November 2013 (25) William A. Nericcio holds court at UCLA’s Chicano A.E. Roman William A. Nericcio Aaron A. Abeyta holds court at Studies Research Center to rapt crowd UCLA’s Chicano ... Aaron Michael Morales Join "La Comida" Abelardo Lalo Delgado Revolution! Are You Achy Obejas Ready? Ada Limón Latina spec lit bio, Lit festival, writers Aldo Alvarez worksho... Alex Espinoza More Reports on the Alfredo Vea Writing Life Alicia Gaspar de Alba Chicanonautica: Chasing the Alisa Valdes Invention of Morel Alma Flor Ada Acr... Alma Luz Villanueva Marisol McDonald and the Clash Alvaro Huerta Bash/Marisol Amelia M.L. Montes McDona... Amy Tintera Gluten-free Chicano. Desperado Tours Américo Paredes Stanford. New... Ana Castillo There is a full moon in Andres Resendez my backyard. Angel Vigil flesh to bone Angela de Hoyos Kids' latino bks; Lit Ashley Pérez agents; Banned Bk; killer ra... Benjamin Alire Sáenz Weekend Update Blas Manuel De Luna Cuentos que celebran C.M. Mayo la diversidad Carmen Lomas Garza Just In Case Carmen Tafolla Review: Villanueva Charley Trujillo Magic. Veterans Day. On-line Fl... Cherrie L. Moraga Interview with Juan Christine Granados Morales, editor and Dagoberto Gilb publisher .. -

View / Open Huang Oregon 0171A 12343.Pdf

“YES! WE HAVE NO BANANAS”: CULTURAL IMAGININGS OF THE BANANA IN AMERICA, 1880-1945 by YI-LUN HUANG A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Yi-lun Huang Title: “Yes! We Have No Bananas”: Cultural Imaginings of the Banana in America, 1880-1945 This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the English Department by: Mary Wood Chairperson Mark Whalan Core Member Courtney Thorsson Core Member Pricilla Ovalle Core Member Helen Southworth Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2018 ii © 2018 Yi-lun Huang iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Yi-lun Huang Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2018 Title: “Yes! We Have No Bananas”: Cultural Imaginings of the Banana in America, 1880-1945 My dissertation project explores the ways in which the banana exposes Americans’ interconnected imaginings of exotic food, gender, and race. Since the late nineteenth century, The United Fruit Company’s continuous supply of bananas to US retail markets has veiled the fruit’s production history, and the company’s marketing strategies and campaigns have turned the banana into an American staple food. By the time Josephine Baker and Carmen Miranda were using the banana as part of their stage and screen costumes between the 1920s and the 1940s, this imported fruit had come to represent foreignness, tropicality, and exoticism. -

224 Nave- Were Confined for Disciplinary Pur- County-Wide Tuberculosis Commlbg Has Been Put Tl Years, the Celebrant and Her !Wall Street'

Joins Sales.Staff Monmouth To House, Wghlands^Woman 101 Of Red Bank Firm Attractive Places Sold 200 German PW's Xmas Seal Sale Edward R. O'Kane of 61 Hub- A group of approximately 200 On Thanksgiving Day bard avenue,. River Plaza, has Join- German prisoners of war. is sched- By Ray H. Stillman uled to arrive at. Fort Monmouth Thanksgiving Day ed the sales staff of the Walker early next week, according to Brig, and Tindall real estate and insur- Gen, Stephen H.Sheirill, command- ance firm, 7 Mechanic street, Red ing general of the Eastern Signal MM. Lavinia Minton's Birthday To Be Bank. ..'-..; One In Highlands, Another Corps Training Center, Proceeds U»ed In Fight . Mr. O'Kane haa been a resident Half of the contingent will be as- of River Plaza fly* year*,' moving In The Holihdel District signed to the separation center, Celebrated With "Open Hoii»e" to this address from Purity Station, and the remainder Is to be placed Against Tuberculosis ,."" N*w Tork. - He has been employed on duty In post overhead activities. Thanksgiving Is tb&AOlst birth- by the government at Raritan ars- Ray H. SttUtaan 4 AwocUtesAf The prisoners will be quartered The annual Monmouth Count] da/ of MM. Lavinla. Mount Min- enal Before bis .employment by Eatontown report "the sale of the in the stockade area formerly oc- Christmas seal campaign op New Ppntiac too, a native of Red Bask frfd a the government he was a salesman Shrewsbury Club attractive home of Cr. and Mrs, cupied by American soldiers' who Free Library ^ Thanksgivirig day, sponsored by th»| resident Of Highland! for the last of over-the-counter securities in Henry A. -

St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924

University of Central Florida STARS St. Cloud Tribune Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-2-1924 St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924 St. Cloud Tribune Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Cloud Tribune by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation St. Cloud Tribune, "St. Cloud Tribune Vol. 17, No. 06, October 02, 1924" (1924). St. Cloud Tribune. 108. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-stcloudtribune/108 1S24 OCTOBER 1924 [SlWl^NtTtJEl-'^^ (SAT ST ll ,11 il TKMTrJL\TI!f A.lv .''...a \V ...... and Watch Heaulli w Wednesday ,i,i.n,.H* I . *-<> HI 1J2J3J4 Tuesday, Beptoa***er SO HO tt o • o s /j 6 j y iu ii M.in.I,iv. Si'lH.'iHl.il- L'II T8 711 Ruaday, iepmubae H aa-M 12 12 13114115116 17118 .Nallli'diiy. S,.|lli'llll.iH- L'T BS T2 Friday, Si'lHl'llilllH- L'II . Sl "1 Vi) Zu Z122 23|24j[25 ^©^jILa^ Thursday, September 28 MI T'J 26i 27i|28|29 30ii31|| ^^^ ^^ TM* Wll.. NO. «—KKJIIT PAGES THIS WEKK. ST. CM) I'll OWKOIaA COINTV, FLORIDA, Till KNI>AV, ,l( Illlll It >, l»2l FIVK CCNTfl TIIK COPY—S3.00 A VKAR ++.:.^..;..:..*.+.j..;..:.+.H.+.:. - • r*-r | •*t-++**H-+*+*+*>+++++-*+++++++•*> + MUCH GOOD WORK DONE SEMINOLE HOTEL RE-OPENED FOR -*-*-»cnr.i BAWD CONCERT kri-wa,, • " TIIK .** 'IIOOI.MASTKK'S * ULnwu,, HAM) OONCKRT FK1IIA1 -:* I'KAVKK * AT City l'urk e} AT NEW SCHOOL UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT LAST SUNDAY NOON THURSDAY WELL *9> + 8 If.