The Biography of a Book the Turku Copy of the 1613 Mercator-Hondius Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download O11 Redux.Pdf

IP* t:44; 4 g r ORHONLU (CENGIZ). iskan tesebbiisii, 1691-1696. --- Osmanli imparatorlugunda asiretleri No. [Istanbul, Univ. Edebiyat Fak. Yayinlari, 998.] Orh. Istanbul, 1963. .9(4.961) Islamic Lib. - -- Another copy. teskilátti. [Istanbul Univ. Edeb. --- Osmanli imparatorlugunda derbend No. 1209.] Fak. Yayinlari, Orh. Istanbul, 1967. .9(4961) ADDITIONS ORHAN (S.T.C.). --- ed. CENTO symposium on the mining & benefaction of fertilizer minerals held in Istanbul ... 1973. See CENTRAL TREATY ORGANIZATION. ORHANG (TORLEIV). - -- See NYBERG (SVEN), O. (T.) and SVENSSON (H.) ORHAN VELI. --- Bütun giileri. Derleyen A. Bezirci. Onaltinci basim. [Turk Yazarlari Dizisi.] Istanbul, 1982. .894351 Orh. ORI, Rabbi. See URI, ben Simeon. ORIA, St. See AURIA,St. ORIANI (ALFREDO). Omnia, a di G. Papini. 2a ed. [Opera - -- La bicicletta. Prefazione cura di Benito Mussolini, 20.] .85391 Ori. Bologna, 1931. [Opere, 1.] - -- La disfatta; romanzo. .85391 Ori. Bari, 1921. [Bibl. Moderna Mondadori, 358 -59.] - -- La disfatta. Ed. integrale. .85391 Ori. [ Milan] 1953. - -- Fino a Dogali. [Opere, 10.] .85391 Ori. Bari, 1918. Omnia, di L. Federzoni. 3a ed. [Opere - -- Fino a dogali. Prefazione a cura di B. Mussolini, 7.] Ori. Bologna, pr. 1935. .85391 -1887. origini della lotta attuale, 476 - -- La lotta politica in Italia; Malavasi e G. Fumagalli. 3 vols. 5a ed. Curata e riveduta ... da A. .3232(45)09 Ori. Firenze, 1921. di Salvatore di Giacomo. [Opera - -- Olocausto; romanzo. Prefazione 22.] Omnia, a cura di Benito Mussolini, .85391 Ori. Bologna, 1925. 3.104. 0r; ideale. - -- La rivolta .301 Bologna, 1912. L. di Benito Mussolini. 3a ed. [010,2.r - -- La rivolta ideale. Prefazione 13.] Omnia, a cura di Benito Mussolini, Ori. -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

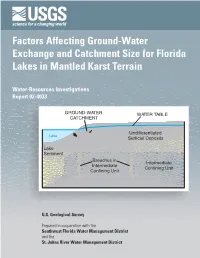

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Asian Cities Depicted by European Painters ― Clues from a Japanese Folding Screen

113 Asian Cities Depicted by European Painters ― Clues from a Japanese Folding Screen Junko NINAGAWA ヨーロッパ人が描いたアジアの諸 都市 ―日本の萬国図屏風を手がかりに 蜷 川 順 子 東京の三の丸尚蔵館が所蔵する八曲一双の萬国図屏風には、制作当時の日本に知られ ていた最新の世界のイメージが描かれている。その主要な源泉は1609年のいわゆるブラ ウ=カエリウスの地図だと考えられるが、タイトルに名前のあるブラウ(1571‒1638)が1606 年に制作し1607年に出版したメルカトール図法による世界地図が、本件と深くかかわって いる。この地図は、その正確さ、地理的情報の新しさ、装飾の美しさなどの点で評判が 高く、これを借用したり模倣したりする他の地図制作者も少なくなかった。カエリウス(1571 ‒c. 1646)もそうした業者のひとりで、1609年に上述のブラウの世界地図を正確に模倣し たブラウ = カエリウスの地図を出版した。 カトリック圏のポルトガル人やスペイン人は、プロテスタント圏の都市アムステルダムで活 躍していたブラウの地図をその市場で購入することもできたが、カトリック圏の都市アント ウェルペンの出身であるカエリウスの方が接触しやすかったものと思われる。おそらくは 彼らの要請により、自身も優れた地図制作者であったカエリウスが1606/07年のブラウの 世界地図を正確に模倣し、そのことによる業務上の係争を避けるために、制作後ただち に同市から出帆する船の積荷に加えさせたのであろう。 ポルトガル人がこの地図を日本にもたらし、そのモチーフを使った屏風の制作に関わっ たことは明らかである。都市図のもっとも大きい区画をポルトガルの地図が占め、1606/07 年のオランダの地図にはなかったカトリックの聖都ローマの都市図が上段の中心付近に置 かれている。ポルトガル領内の第二の都市インドのゴアが、地図の装飾の配置から考えて ほぼ中心にあるのは、インドを天竺として重視した仏教徒にアピールするためであろうか。 こうすることで、日本におけるポルトガル人の存在を認めるよう日本の権力者に促す意図が あったのかもしれない。ここではさらに、制作に関わったと思われる日本人画家の関心な どを、アジアの都市図の描き方を手がかりに論じた。 114 A Japanese folding screen illustrated with twenty-eight cityscapes and portraits of eight sovereigns of the world [Fig. 1], the pair to a left-hand one depicting a world map and people of diff erent nations [Fig. 2], preserved in the Sannomaru Shōzōkan, or the Museum of the Imperial Collections, Tokyo, is widely recognized as one of the earliest world imageries known to Japan at that time 1). It is said to have been a tribute pre- Fig. 1 Map of Famous Cities [Bankoku e-zu](Right Screen) Momoyama period(the late 16th‒the early 17th -

Digitization of Maps and Atlases and the Use of Analytical Bibliography1

Digitization of Maps and Atlases and the Use of Analytical Bibliography1 Wouter Bracke Gérard Bouvin Royal Library of Belgium Royal Library of Belgium Université libre de Bruxelles [email protected] [email protected] Benoît Pigeon Royal Library of Belgium [email protected] From 2006 to 2008 the Royal Library of Belgium (http://www.kbr.be/) par- ticipated in a European Commission funded project for the development of research services in the field of old maps. This chapter presents this new Internet-accessible scientific tool (www.digmap.eu/), evaluates its possibili- ties and flaws, and makes suggestions for the future, specifically in reaction to (or better, in line with) Anthony Grafton's critical observations on digital libraries. The introductory section will concentrate on the nature of maps and the history of cartography in relation to digital databanks of map im- ages. For practical reasons, in describing Digmap we take examples mainly from the collection of the Royal Library of Belgium. Introduction The creation of digital online databanks may have many particular goals, from the conservation or preservation of a collection to its substitution, but its most prominent aim certainly is to improve the collection’s accessibility. This implies facilitating access to information about that collection, in other words, improving communication on the collection’s content. This commu- nication requires structured information, and structuring information is es- sentially what digital (as well as other) databanks are about. 1 This contribution benefited by a short correspondence between W. Bracke and Tony Campbell in December 2007 when preparing the first Digmap workshop (cf. -

Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa

Hydrogeology and Simulation of Ground- Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa By Patrick Tucci (U.S. Geological Survey) and Robert M. McKay (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Geological Survey) Prepared in cooperation with The Iowa Department of Natural Resources – Water Supply Bureau City of Iowa City Johnson County Board of Supervisors City of Coralville The University of Iowa City of North Liberty City of Solon Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5266 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Tucci, Patrick and McKay, Robert, 2006, Hydrogeology and simulation of ground-water flow in the Silurian-Devonian aquifer system, Johnson County, Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations -

Altea Gallery

Front cover: item 32 Back cover: item 16 Altea Gallery Limited Terms and Conditions: 35 Saint George Street London W1S 2FN Each item is in good condition unless otherwise noted in the description, allowing for the usual minor imperfections. Tel: + 44 (0)20 7491 0010 Measurements are expressed in millimeters and are taken to [email protected] the plate-mark unless stated, height by width. www.alteagallery.com (100 mm = approx. 4 inches) Company Registration No. 7952137 All items are offered subject to prior sale, orders are dealt Opening Times with in order of receipt. Monday - Friday: 10.00 - 18.00 All goods remain the property of Altea Gallery Limited Saturday: 10.00 - 16.00 until payment has been received in full. Catalogue Compiled by Massimo De Martini and Miles Baynton-Williams To read this catalogue we recommend setting Acrobat Reader to a Page Display of Two Page Scrolling Photography by Louie Fascioli Published by Altea Gallery Ltd Copyright © Altea Gallery Ltd We have compiled our e-catalogue for 2019's Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Fair in two sections to reflect this year's theme, which is Firsts The catalogue starts with some landmarks in printing history, followed by a selection of highlights of the maps and books we are bringing to the fair. This year the fair will be opened by Stephen Fry. Entry on that day is £20 but please let us know if you would like admission tickets More details https://www.firstslondon.com On the same weekend we are also exhibiting at the London Map Fair at The Royal Geographical Society Kensington Gore (opposite the Albert Memorial) Saturday 8th ‐ Sunday 9th June Free admission More details https://www.londonmapfairs.com/ If you are intending to visit us at either fair please let us know in advance so we can ensure we bring appropriate material. -

Donald Heald Rare Books a Selection of Rare Books

Donald Heald Rare Books A Selection of Rare Books Donald Heald Rare Books A Selection of Rare Books Donald Heald Rare Books 124 East 74 Street New York, New York 10021 T: 212 · 744 · 3505 F: 212 · 628 · 7847 [email protected] www.donaldheald.com Fall 2015 Americana: Items 1 - 28 Travel and Cartography: Items 29 - 51 Natural History: Items 52 - 76 Color Plate & Illustrated: Items 77 - 91 Miscellany: Items 92 - 100 All purchases are subject to availability. All items are guaranteed as described. Any purchase may be returned for a full refund within ten working days as long as it is returned in the same condition and is packed and shipped correctly. The appropriate sales tax will be added for New York State residents. Payment via U.S. check drawn on a U.S. bank made payable to Donald A. Heald, wire transfer, bank draft, Paypal or by Visa, Mastercard, American Express or Discover cards. AMERICANA 1 [AFRICAN AMERICANA] - Worthington G. SNETHEN. The Black Code of the District of Columbia in Force September 1st, 1848. New York: The A[merican] and F[oreign] Anti-Slavery Society, 1848. 8vo (8 5/8 x 5 1/4 inches). 61, [1, blank], [1], [1, blank] pp. Ad leaf in rear. Expertly bound to style in half black morocco over period marbled paper covered boards. Rare printing of the antebellum laws relating to African Americans in Washington, D.C. The author, a Washington D.C. attorney and the former solicitor of the General Land Office, notes on an advertisement leaf in the rear that he has “nearly completed the Black Code of each of the States of the Union. -

Visscher Redrawn

VISSCHER REDRAWN By Robin Reynolds after Claes Jansz Visscher 1 Visscher Redrawn is a pen-and-ink revision of Dutch engraver Claes Jansz Visscher’s London panorama, published in 1616. In it, 21st century artist Robin Reynolds depicts modern London, arranged on the fantastic Visscher landscape. The new work was first exhibited at London’s Guildhall Art Gallery from February to November 2016, as part of the City of London’s William Shakespeare 400th and Great Fire 350th anniversary programmes. The piece includes references to the Great Fire and the London Blitz – two events that reshaped London – and hidden in the drawing are visual references to all of Shakespeare’s major works. You can find the clues, drawn from Shakespeare’s texts, on pages 17-20. While researching Visscher Redrawn, Robin Reynolds explored the life and works of Visscher and his associates in the Dutch Golden Age. Included in this handbook is his essay, Secrets in the Sky, setting out the evidence that he believes explains how the Visscher panorama was compiled by a man who had never set eyes on London. 1 CONTENTS THE 2016 PROJECT Claes Jansz Visscher 4-5 The idea of a modern London revision would be 2016 – the 400th The secret was a scroll-box, designed view in the fashion of the 1616 anniversary of the Visscher version and built by Reading carpenter Robin Reynolds 6-7 Visscher panorama surfaced in the – so again, the idea was put on ice. Graham Kemp. This permitted the mid-1990s, when Robin Reynolds artist to work on one section of the The Visscher panorama: factfile 8-9 was pursuing fantasy drawings as Early in 2014, encouraged by drawing while the rest of it was safe a hobby. -

FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS Covers 2012 Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5

IMCSJOURNAL S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS covers 2012_Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5 THE MAP HOUSE OF LONDON (established 1907) Antiquarian Maps, Atlases, Prints & Globes 54 BEAUCHAMP PLACE KNIGHTSBRIDGE LONDON SW3 1NY Telephone: 020 7589 4325 or 020 7584 8559 Fax: 020 7589 1041 Email: [email protected] www.themaphouse.com JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MAP COLLECTORS’ SOCIETY FOUNDED S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 1980 FEATURES Mercator and his ‘Atlas of Europe’ 13 Self-protection, official obligations and the pursuit of truth Peter Barber High in the Andes partii 25 Further adventures of the French Academy expedition to Peru Richard Smith ‘The Dutch colony of The Cape of Good Hope’ 30 A map by L.S. De la Rochette Roger Stewart REGULAR ITEMS A Letter from the Chairman 3 Hans Kok From the Editor’s Desk 5 Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird IMCoS Matters 7 Mapping Matters 37 Worth a Look 46 You Write to Us 49 Book Reviews 53 Copy and other material for our next issue (Summer 2013) should be submitted by 1 April 2013. Editorial items should be sent to the Editor Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird, email [email protected] or 14 Hallfield, Quendon, Essex CB11 3XY United Kingdom Consultant Editor Valerie Newby Designer Catherine French Advertising Jenny Harvey, 27 Landford Road, Putney, London SW15 1AQ United Kingdom Tel +44 (0)20 8789 7358, email [email protected] Please note that acceptance of an article for publication gives IMCoS the right to place it on our website. -

Ortelius's Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570)

Ortelius’s Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570) by Giorgio Mangani (Ancona, Italy) Paper presented at the 18th International Conference for the History of Cartography (Athens, 11-16th July 1999), in the "Theory Session", with Lucia Nuti (University of Pisa), Peter van der Krogt (University of Uthercht), Kess Zandvliet (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), presided by Dennis Reinhartz (University of Texas at Arlington). I tried to examine this map according to my recent studies dedicated to Abraham Ortelius,1 trying to verify the deep meaning that it could have in his work of geographer and intellectual, committed in a rather wide religious and political programme. Ortelius was considered, in the scientific and intellectual background of the XVIth century Low Countries, as a model of great morals in fact, he was one of the most famous personalities of Northern Europe; he was a scholar, a collector, a mystic, a publisher, a maps and books dealer and he was endowed with a particular charisma, which seems to have influenced the work of one of the best artist of the time, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Dealing with the deep meaning of Ortelius’ atlas, I tried some other time to prove that the Theatrum, beyond its function of geographical documentation and succesfull publishing product, aimed at a political and theological project which Ortelius shared with the background of the Familist clandestine sect of Antwerp (the Family of Love). In short, the fundamentals of the familist thought focused on three main points: a) an accentuated sensibility towards a mysticism close to the so called devotio moderna, that is to say an inner spirituality searching for a direct relation with God. -

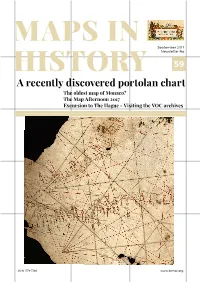

A Recently Discovered Portolan Chart the Oldest Map of Monaco? the Map Afternoon 2017 Excursion to the Hague - Visiting the VOC Archives

MAPS IN September 2017 Newsletter No HISTORY 59 A recently discovered portolan chart The oldest map of Monaco? The Map Afternoon 2017 Excursion to The Hague - Visiting the VOC archives ISSN 1379-3306 www.bimcc.org 2 SPONSORS EDITORIAL 3 Contents Intro Dear Map Friends, Exhibitions Paulus In this issue we are happy to present not one, but two Aventuriers des mers (Sea adventurers) ...............................................4 scoops about new map discoveries. Swaen First Joseph Schirò (from the Malta Map Society) Looks at Books reports on an album of 148 manuscript city plans dating from the end of the 17th century, which he has Internet Map Auctions Finding the North and other secrets of orientation of the found in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Of course, travellers of the past ..................................................................................................... 7 in Munich, Marianne Reuter had already analysed this album thoroughly, but we thought it would be March - May - September - November Orbis Disciplinae - Tributes to Patrick Gautier Dalché ... 9 appropriate to call the attention of all map lovers to Maps, Globes, Views, Mapping Asia Minor. German orientalism in the field it, since it includes plans from all over Europe, from Atlases, Prints (1835-1895) ............................................................................................................................ 12 Flanders to the Mediterranean. Among these, a curious SCANNING - GEOREFERENCING plan of the rock of Monaco has caught the attention of Catalogue on: AND DIGITISING OF OLD MAPS Rod Lyon who is thus completing the inventory of plans www.swaen.com History and Cartography of Monaco which he published here a few years ago. [email protected] The discovery of the earliest known map of Monaco The other remarkable find is that of a portolan chart, (c.1589) ..........................................................................................................................................15 hitherto gone unnoticed in the Archives in Avignon.