Steamer Ducks)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Patagonia & Central Chile

WILD PATAGONIA & CENTRAL CHILE: PUMAS, PENGUINS, CONDORS & MORE! NOVEMBER 1–18, 2019 Pumas simply rock! This year we enjoyed 9 different cats! Observing the antics of lovely Amber here and her impressive family of four cubs was certainly the highlight in Torres del Paine National Park — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & FERNANDO DIAZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Sensational, phenomenal, outstanding Chile—no superlatives can ever adequately describe the amazing wildlife spectacles we enjoyed on this year’s tour to this breathtaking and friendly country! Stupendous world-class scenery abounded with a non-stop array of exciting and easy birding, fantastic endemics, and super mega Patagonian specialties. Also, as I promised from day one, everyone fell in love with Chile’s incredible array of large and colorful tapaculos; we enjoyed stellar views of all of the country’s 8 known species. Always enigmatic and confiding, the cute Chucao Tapaculo is in the Top 5 — Photo: Andrew Whittaker However, the icing on the cake of our tour was not birds but our simply amazing Puma encounters. Yet again we had another series of truly fabulous moments, even beating our previous record of 8 Pumas on the last day when I encountered a further 2 young Pumas on our way out of the park, making it an incredible 9 different Pumas! Our Puma sightings take some beating, as they have stood for the last three years at 6, 7, and 8. For sure none of us will ever forget the magical 45 minutes spent observing Amber meeting up with her four 1- year-old cubs as they joyfully greeted her return. -

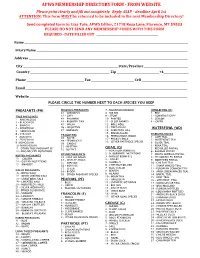

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

Taxonomy and Identification of Steamer-Ducks (Anatidae : Tachyeres)

Taxonomy and Identification of STEAMER-DUCKS (Anatidae: Tachyeres) Bradley C. Livezey and Philip S. Humphrey u^C ^^, ^ Ernst Mayr lArary Zoology - P ^ ^ %weiim of Compara»ve Harvard University THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS. MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATIONS The University of Kansas Publications. Museum of Natural History, beginning with volume I in 1946. was discontinued with volume 20 in 1971. .Shorter research papers formerly published in the above series are now published as The Universitv of Kansas Museum of Natural History Occasional Papers. The University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publications began with number 1 in 1946. Longer research papers are published in that series. Monographs of the Museum of Natural llisioiy were initiated in 1970. Authors shouldcontact the managing editor regarding style and submission procedures before manuscript submission. All tiianuscripts are subjected to critical review by intra- and extramural specialists; final acceptance is at the discretion of the Director. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Occasional Papers and Miscellaneous Publications are lypeset using Microsoff " Word and Aldus PageMaker" on a Macintosh computer. Institutional libraries interested in exchanging publications may obtain the Occasional Papers and Miscellaneous Publications by addressing the E.xchange Librarian, The University of Kansas Library, Lawrence. Kansas 6604.'S-2K0() LISA. Individuals may purchase separate numbers from the Office of Publications, Muscimh oI Nalmal History, The LIniversily of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 6604.^-24.S4 I SA. f-'ninl Cover: ihc jour species oj Sieaiueriliicks asjollows: I pper lefi \\ liiieheiiiled I'll^^litlcss Sieanier- (liicks (I'hoto;^rapli h\ R Siraiiei ki: Cpper rii^hl—Moiielluiue I- li;^luless Steamer -iliieks iPlioloi^rapli h\ — ('. -

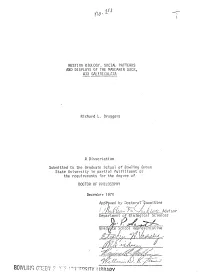

Nesting Biology. Social Patterns and Displays of the Mandarin Duck, a Ix Galericulata

pi)' NESTING BIOLOGY. SOCIAL PATTERNS AND DISPLAYS OF THE MANDARIN DUCK, A_IX GALERICULATA Richard L. Bruggers A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1974 ' __ U J 591913 W A'W .'X55’ ABSTRACT A study of pinioned, free-ranging Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) was conducted from 1971-1974 at a 25-acre estate. The purposes 'were to 1) document breeding biology and behaviors, nesting phenology, and time budgets; 2) describe displays associated with copulatory behavior, pair-formation and maintenance, and social encounters; and 3) determine the female's role in male social display and pair formation. The intensive observations (in excess of 400 h) included several full-day and all-night periods. Display patterns were recorded (partially with movies) arid analyzed. The female's role in social display was examined through a series of male and female introductions into yearling and adult male "display parties." Mandarins formed strong seasonal pair bonds, which re-formed in successive years if both individuals lived. Clutches averaged 9.5 eggs and were begun by yearling females earlier and with less fertility (78%) than adult females (90%). Incubation averaged 28-30 days. Duckling development was rapid and sexual dimorphism evident. 9 Adults and yearlings of both sexes could be separated on the basis of primary feather length; females, on secondary feather pigmentation. Mandarin daily activity patterns consisted of repetitious feeding, preening, and loafing, but the duration and patterns of each activity varied with the social periods. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

Which Birds Can't Fly? a List of Birds That Are Flightless

Which Birds Can't Fly? A List of Birds That Are Flightless worldatlas.com/articles/flightless-birds-from-around-the-world.html May 17, 2016 An Australian Emu posing for the camera. Below we have listed a few notable flightless birds, though obviously not all of these largely land-restricted avian species. Other notable flightless bird species include emus, rheas, certain teals and scrubfowls, grebes, cormorants, and various rails, just to name a few. Cassowary 1/11 The flightless birds of Papua New Guinea, northeastern Australia, and some other islands of Oceania, the cassowaries are quite well known for their fierce reputation. Though they cannot fly they can definitely scare away their enemies with their violent nature and hidden claws. Many human and animal deaths have been reported to be caused by these birds. The birds are omnivorous in nature, feeding on fruits, fungi, insects and other species. Among the three species of cassowary, the southern cassowary is the third tallest bird in the world and is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to its steadily decreasing numbers. Kakapo 2/11 The kakapo, a unique species of flightless parrot, is endemic to New Zealand and is almost on the verge of extinction, classified as critically endangered by the IUCN. The fact that kakapos are nocturnal in nature, flightless and do not exhibit any male parental care, makes them different from other parrots of the world. They are also the heaviest among the parrots and exhibit the lek system of mating. For years these birds have been hunted by the Maori tribes of New Zealand for meat and feathers. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No

BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard RHEIFORMES: Rheidae 1 Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata s TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 2 Elegant Crested-Tinamou Eudromia elegans s ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 3 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata s ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata s 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 6 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus s 7 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba s 8 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta s 9 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida s 10 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus s 11 Flightless Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres s 12 White-headed Steamer-Duck Tachyeres leucocephalus s 13 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides s 14 Spectacled Duck Speculanas specularis s 15 Brazilian Teal Amazonetta brasiliensis s 16 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata s 17 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix s 18 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera s 19 Red Shoveler Anas platalea s 20 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica s 21 Silver Teal Anas versicolor s 22 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris s 23 Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca s 24 Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla s 25 Lake Duck Oxyura vittata s PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 26 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland s 27 Great Grebe Podiceps major s 28 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis s PHOENICOPTERIFORMES: Phoenicopteridae 29 Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis s SPHENISCIFORMES: Spheniscidae 30 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus s 31 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua s 32 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus s PROCELLARIIFORMES: Diomedeidae 33 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris s Page 1 of 6 BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No.