Welfare Assessment for Captive Anseriformes: a Guide for Practitioners and Animal Keepers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coelomic Liposarcoma in an African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus)

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Case Report SOJ Veterinary Sciences Open Access Coelomic Liposarcoma In An African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus) Jason D Struthers1* and Geoffrey W Pye2 1From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. 2Animals, Science, and Environment, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, 1200 N Savannah Circ, Bay Lake, Florida 32830, USA. Received: 25 May, 2018; Accepted: 11 June, 2018; Published: 12 June, 2018 *Corresponding author: : Jason D. Struthers,From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. E-mail: [email protected] abutted many tissues, including the ventriculus, kidney, oviduct, Abstract and, most closely, the cloaca. The mass was dissected and isolated A morbid African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) developed open- from the surrounding viscera. On section, the mass was greasy, mouth breathing and died during physical exam. Necropsy revealed bacterial salpingitis and a coelomic liposarcoma. Death resulted from (necrosis). The oviduct’s serosa was diffusely grey to light brown a combination of poor body condition, infection, stress of handling, andsoft, wasand markedlymottled tan distended to light red by withsoft tooccasional granular, greygrey firm to brown areas and compromised respiratory and cardiovascular function related to the coelomic liposarcoma. viscid material. A swab of the lumen was submitted for aerobic bacterial culture. Keywords: coelom; duck; liposarcoma; Nettapus auritus; oil red O; pygmy goose Introduction A zoo—born six-year old female African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) was found recumbent and lethargic in her enclosure. -

Black-Bellied Whistling-Duck Yellow-Billed Cuckoo Fulvous

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Yellow-billed Cuckoo Willet* Band-rumped Storm-Petrel Northern Flicker Bewick's Wren Fulvous Whistling-Duck Black-billed Cuckoo Greater Yellowlegs Wood Stork Pileated Woodpecker Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Snow Goose* Common Nighthawk Wilson's Phalarope Magnificent Frigatebird American Kestrel Golden-crowned Kinglet Ross's Goose Chuck-will's-widow Red-necked Phalarope Northern Gannet Merlin* Ruby-crowned Kinglet Greater White-fronted Goose Eastern Whip-poor-will Red Phalarope Anhinga Peregrine Falcon Eastern Bluebird Brant Chimney Swift Great Skua Great Cormorant Monk Parakeet Veery Cackling Goose Ruby-throated Hummingbird Pomarine Jaeger Double-crested Cormorant Ash-throated Flycatcher Gray-cheeked Thrush Canada Goose Rufous Hummingbird Parasitic Jaeger American White Pelican Great Crested Flycatcher Bicknell's Thrush Mute Swan Clapper Rail Long-tailed Jaeger Brown Pelican Western Kingbird Swainson's Thrush Trumpeter Swan King Rail Dovekie American Bittern Eastern Kingbird Hermit Thrush Tundra Swan Virginia Rail Thick-billed Murre Least Bittern Gray Kingbird Wood Thrush Wood Duck Sora Razorbill Great Blue Heron* Scissor-tailed Flycatcher American Robin Atlantic Puffin Great Egret Blue-winged Teal Common Gallinule Fork-tailed Flycatcher Varied Thrush Black-legged Kittiwake Snowy Egret Northern Shoveler American Coot Olive-sided Flycatcher Gray Catbird Sabine's Gull Little Blue Heron Gadwall Purple Gallinule Eastern Wood-Pewee Brown Thrasher Bonaparte's Gull Tricolored Heron Eurasian Wigeon Yellow Rail Yellow-bellied -

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

The Systematic Position of the Ring-Necked Duck

460 Hollister, Ring-necked Duck. [o"t. into consideration the evanescence of the diagnostic markings, and the inaccessibility of the coastal marshes where the bird breeds, together with the fact that the few ornithologists who seem to have visited them were generally armed only with cameras, it is perhaps not so odd after all. In assembling the data upon which these notes are based, besides those already mentioned, to whom I am particularly indebted, my thanks are due to Messrs. Stanley C. Arthur, O. Bangs, Howarth S. Boyle, William Brewster, Jonathan Dwight, J. H. Flemming, Harry C. Oberholser, Wilfred H. Osgood, T. S. Palmer, H. S. Swarth, P. A. Taverner, W. E. Clyde Todd, and John E. Thayer. THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE RING-NECKED DUCK. BY N. HOLLISTER. The group of fuliguline Ducks now called Marila in the American ' Ornithologists' Union Check-List ' has had its full share of nomen- clatorial shifts and changes, and many schemes have been proposed for its division into genera or subgenera. It has always seemed to me that the question of the number and rank of the named super- specific sections within this group is of little importance in com- parison to the error involved in the sequence given the species in the ' Check-List,' where the Canvasback is placed between the Redhead and the Scaups, and the Ring-necked Duck is put at the end of the series in the typical subgenus Marila. From a study of the literature of American Ducks it is evident that the belief prevails that the Ring-necked Duck (Marila col- laris) is a Scaup, very closely related to the Greater and Lesser Bluebills (Marila marila and M. -

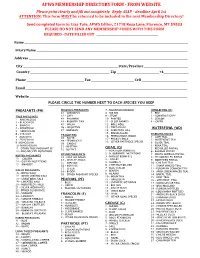

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

King Eiders Mated with Common Eiders in Iceland

KING EIDERS MATED WITH COMMON EIDERS IN ICELAND BY OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR. HE Common Eider (Somateriu mollissima) is one of Icelands’ most T abundant birds, with an estimated breeding population of a half million individuals (see Pettingill, 1959). Th e majority nest in colonies whose sizes range from a few pairs to many hundreds. From May 24 to 27, 1958, it was my good fortune to study and film one of the largest colonies (5,000 nests), situated on the farm of Gisli Vagnsson, along the DyrafjSrdur in Northwest Iceland. Egg-laying at this time was virtually completed, with incubation just getting under way. In my earlier paper (op. cit.) I have described the colony and pointed out that the males were present, each one stationed close to a nest while his mate sat on it. Many nests were near together-in a few cases as close as two feet, with the result that there was marked hostility among the guarding males. Presumably the males departed from the colony after the first ten days of incubation as they did on the Inner Farne (Tinbergen, 1958)) an island off the northeast coast of England. Before I visited the Vagnsson colony, Dr. Finnur Gudmundsson, Curator in the Natural History Museum at Reykjavik, told me that I should expect to find from one to several male King Eiders (S. spectabilis) mated with female Common Eiders. He had noted many mixed pairs himself in various Iceland colonies and once published an account of his observations (Gudmundsson, 1932:96-97). He went on to say that such matings are of “frequent occur- rence” in Iceland and have been known about since the 18th Century. -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

References.Qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771

Ducks_References.qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771 References Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 1994. Dverggås Anser Adams, J.S. 1971. Black Swan at Lake Ellesmere. erythropus—en truet art i Norge. Vår Fuglefauna 17: 70–80. Wildl. Rev. 3: 23–25. Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 2003. Moult and autumn Adams, P.A., Robertson, G.J. and Jones, I.L. 2000. migration of non-breeding Fennoscandian Lesser White- Time-activity budgets of Harlequin Ducks molting in fronted Geese Anser erythropus mapped by satellite the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Condor 102: 703–08. telemetry. Bird Conservation International 13: 213–226. Adrian, W.L., Spraker, T.R. and Davies, R.B. 1978. Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J. and Nagy, S. 1996. The Lesser Epornitics of aspergillosis in Mallards Anas platyrhynchos White-fronted Goose monitoring programme,Ann. Rept. in north central Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis. 14: 212–17. 1996, NOF Rappportserie, No. 7. Norwegian Ornitho- AEWA 2000. Report on the conservation status of logical Society, Klaebu. migratory waterbirds in the agreement area. Technical Series Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J., Syroechkovski Jr., E.E. and No. 1.Wetlands International,Wageningen, Netherlands. Kostadinova, I. 1997. The Lesser White-fronted Goose Afton, A.D. 1983. Male and female strategies for Monitoring Programme.Annual Report 1997. Klæbu, reproduction in Lesser Scaup. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis. Norwegian Ornithological Society. NOF Raportserie, Univ. North Dakota, Grand Forks, US. Report no. 5-1997. Afton, A.D. 1984. Influence of age and time on Abbott, C.C. 1861. Notes on the birds of the Falkland reproductive performance of female Lesser Scaup.