Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coelomic Liposarcoma in an African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus)

www.symbiosisonline.org Symbiosis www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Case Report SOJ Veterinary Sciences Open Access Coelomic Liposarcoma In An African Pygmy Goose (Nettapus Auritus) Jason D Struthers1* and Geoffrey W Pye2 1From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. 2Animals, Science, and Environment, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, 1200 N Savannah Circ, Bay Lake, Florida 32830, USA. Received: 25 May, 2018; Accepted: 11 June, 2018; Published: 12 June, 2018 *Corresponding author: : Jason D. Struthers,From the Animal Health Institute, Department of Pathology and Population Medicine, 5725 W. Utopia Rd., Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308, USA. E-mail: [email protected] abutted many tissues, including the ventriculus, kidney, oviduct, Abstract and, most closely, the cloaca. The mass was dissected and isolated A morbid African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) developed open- from the surrounding viscera. On section, the mass was greasy, mouth breathing and died during physical exam. Necropsy revealed bacterial salpingitis and a coelomic liposarcoma. Death resulted from (necrosis). The oviduct’s serosa was diffusely grey to light brown a combination of poor body condition, infection, stress of handling, andsoft, wasand markedlymottled tan distended to light red by withsoft tooccasional granular, greygrey firm to brown areas and compromised respiratory and cardiovascular function related to the coelomic liposarcoma. viscid material. A swab of the lumen was submitted for aerobic bacterial culture. Keywords: coelom; duck; liposarcoma; Nettapus auritus; oil red O; pygmy goose Introduction A zoo—born six-year old female African pygmy goose (Nettapus auritus) was found recumbent and lethargic in her enclosure. -

Black Swans, Or the Limits of Statistical Modelling

Black swans, or the limits of statistical modelling Eric Marsden <[email protected]> Do I follow indicators that could tell me when my models may be wrong? On the 1001st day, a little before Thanksgiving, the turkey has a surprise. A turkey is fed for 1000 days. Each passing day confirms to its statistics department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance”. 2 / 58 A turkey is fed for 1000 days. Each passing day confirms to its statistics department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance”. On the 1001st day, a little before Thanksgiving, the turkey has a surprise. 2 / 58 Things that have never happened before, happen all the time. — Scott D. Sagan, The Limits of Safety: Organizations, ‘‘ Accidents, And Nuclear Weapons, 1993 In risk analysis, these are called “unexampled events” or “outliers” or “black swans”. 3 / 58 The term “black swan” was used in16th century discussions of impossibility (all swans known to Europeans were white). Explorers arriving in Australia discovered a species of swan that is black. The term is now used to refer to events that occur though they had been thought to be impossible. 4 / 58 Black swans ▷ Characteristics of a black swan event: • an outlier • lies outside the realm of regular expectations • nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility • carries an extreme impact ▷ Note that: • in spite of its outlier status, it is often easy to produce an explanation for the event after the fact • a black swan event may be a surprise for some, but not for others; it’s a subjective, knowledge-dependent notion • warnings about the event may have been ignored because of strong personal and organizational resistance to changing beliefs and procedures Source: The Black Swan: the Impact of the Highly Improbable, N. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

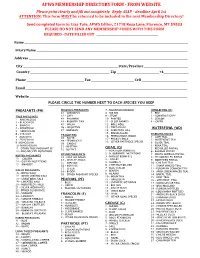

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

Wetlands Australia

Wetlands Australia National wetlands update August 2014—Issue No 25 Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2014 Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2014 – Issue No 25 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au This report should be attributed as ‘Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2015 – Issue No 25, Commonwealth of Australia 2014’ The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Cover images Front cover: Wetlands provide important habitats for waterbirds, such as this adult great egret (Ardea modesta) at Leichhardt Lagoon in Queensland (© Copyright, Brian Furby) Back cover: Inland wetlands, like Narran Lakes Nature Reserve Ramsar site in New South Wales, support high numbers of waterbird breeding and provide refuge for birds during droughts (© Copyright, Dragi Markovic) ii / Wetlands Australia August 2014 Contents Introduction to Wetlands Australia August -

Newly Established Breeding Sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta Leucopsis in North-Western Europe – an Overview of Breeding Habitats and Colony Development

244 N. FEIGE et al.: New established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose in North-western Europe Newly established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis in North-western Europe – an overview of breeding habitats and colony development Nicole Feige, Henk P. van der Jeugd, Alexandra J. van der Graaf, Kjell Larsson, Aivar Leito & Julia Stahl Feige, N., H. P. van der Jeugd, A. J. van der Graaf, K. Larsson, A. Leito, A. & J. Stahl 2008: Newly established breeding sites of the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis in North-western Europe – an overview of breeding habitats and colony development. Vogelwelt 129: 244–252. Traditional breeding grounds of the Russian Barnacle Goose population are at the Barents Sea in the Russian Arctic. During the last decades, the population increased and expanded the breeding area by establishing new breeding colonies at lower latitudes. Breeding numbers outside arctic Russia amounted to about 12,000 pairs in 2005. By means of a questionnaire, information about breeding habitat characteristics and colony size, colony growth and goose density were collected from breeding areas outside Russia. This paper gives an overview about the new breeding sites and their development in Finland, Estonia, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands and Belgium. Statistical analyses showed significant differences in habitat characteristics and population parameters between North Sea and Baltic breeding sites. Colonies at the North Sea are growing rapidly, whereas in Sweden the growth has levelled off in recent years.I n Estonia numbers are even decreasing. On the basis of their breeding site choice, the flyway population of BarnacleG eese traditionally breeding in the Russian Arctic can be divided into three sub-populations: the Barents Sea population, the Baltic population and the North Sea population. -

Bird Vulnerability Assessments

Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change, to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia: Bird Vulnerability Assessments Attachment (2) to the Final Report June 2011 Citation: Gonzalez, D., Scott, A. & Miles, M. (2011) Bird vulnerability assessments- Attachment (2) to ‘Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia’. Report prepared for the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board. For further information please contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department of Environment and Natural Resources office. Online information available at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Permissive Licence © State of South Australia through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose subject to the conditions that you (1) attribute the Department as the copyright owner of this publication and that (2) you obtain the prior written consent of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources if you wish to modify the work or offer the publication for sale or otherwise use it or any part of it for a commercial purpose. Written requests for permission should be addressed to: Design and Production Manager Department of Environment and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Department of Water and Environmental Regulation A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands An Ecological Snapshot March 2017—January 2018 W IN N T M E U R T U A S P R R I N E G M M U S Musk duck (Biziura lobata) (Photo: Mark Oliver) The Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands The conservation values of the Vasse-Wonnerup wetlands are recognised on a local, state, national and international level. The wetlands provide habitat to thousands of Australian and migratory water birds as well as supporting the largest breeding population of black swans in the state. In 1990 the wetlands were recognised as a ‘Wetland of International Importance’ under the Ramsar Convention. The wetlands are also one of the most nutrient enriched wetlands in Western Australia, characterised by extensive macroalgae and phytoplankton blooms and occasional major fish kills. Poor water quality in the wetlands is a major concern for the local community. Over the past four years scientists have been working together to investigate options to improve water quality in the wetlands by monitoring seawater inflows through the Vasse surge barrier and modelling options to increase water levels and flows into the Vasse estuary. These trials have successfully shown that seawater inflows can reduce the incidence of harmful phytoplankton blooms and improve conditions for fish in the Vasse Estuary Channel over summer months. What isn’t as well understood is how these management approaches and subsequent increased water levels may impact on the broader wetland system, especially how the ecology of the wetlands responds to changes in the timing and volume of seawater inflow through the surge barriers. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible.