31 Investigation Group III/Office 9 Public Document July 30, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public M&A 2013/14: the Leading Edge

Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge June 2014 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Contents 2 Introduction 31 Italy 31 Deal activity 4 Global market trend map 31 Market trends 6 The leading edge: country perspectives 32 Case studies 6 Austria 34 Japan 6 Deal activity 34 Deal activity 6 Market trends 34 Market trends 6 Changes to the legislative framework 35 Case study 7 Case study 36 Netherlands 8 Belgium 36 Deal activity 8 Market trends 36 Market trends 8 Changes to the legislative framework 37 Changes to the legislative framework 9 Case study 38 Points to watch 39 Case studies 10 China 10 Deal activity 40 Spain 11 Market trends 40 Deal activity 11 Case study 40 Market trends 41 Changes to the legislative framework 12 EU 42 Points to watch 12 Changes to the legislative framework 43 Case studies 14 France 44 UK 14 Market trends 44 Deal activity 15 Changes to the legislative framework 45 Market trends 16 Case studies 45 Changes to the legislative framework 19 Germany 46 Deal protection measures 19 Deal activity 47 Points to watch 20 Market trends 48 Case study 22 Case study 50 US 24 Hong Kong and Singapore 50 Deal activity 24 Deal activity 50 Market trends and judicial and 25 Market trends legislative developments 28 Market trends 51 Litigation as a cost of doing business 29 Case study 53 Case study 54 Contacts Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP 1 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Introduction Market trends 2013 saw a modest increase in global public M&A activity. -

24 June 2013 Not for Release, Publication Or Distribution, in Whole

24 June 2013 Not for release, publication or distribution, in whole or in part, in or into any jurisdiction where to do so would constitute a violation of the relevant laws of such jurisdiction Update from the Independent Committee of the Board of Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation PLC (the "Company" or "ENRC") Independent Committee's response to the Offer for ENRC The Independent Committee of the Board of ENRC (the "Independent Committee") notes the Rule 2.7 announcement (the "Announcement") earlier today by Eurasian Resources Group B.V. (the "Eurasian Resources Group" or the “Offeror”), a newly incorporated company formed by a consortium comprising Alexander Machkevitch, Alijan Ibragimov, Patokh Chodiev and the State Property and Privatisation Committee of the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Kazakhstan (together, the "Consortium"), of the terms of an offer to be made by Eurasian Resources Group to acquire all of the issued and to be issued share capital of ENRC (other than the ENRC Shares already held by the Offeror). The defined terms in this announcement shall have the meaning given to them in the Announcement unless indicated otherwise herein. Under the terms of the Offer, Relevant ENRC Shareholders would receive US$2.65 in cash and 0.230 Kazakhmys Consideration Shares for each ENRC Share. The Offer values ENRC at 234.3 pence per ENRC Share (having an aggregate value of approximately £3.0 billion) based on the mid-market closing share price of Kazakhmys on Friday 21 June 2013. This represents a price which is lower than the proposal put to the Independent Committee by the Consortium on 16 May 2013 of 260 pence per ENRC Share and constitutes: • a discount of 27 per cent. -

Leadership Transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Implications for Policy and Stability in Central Asia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-09 Leadership transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan implications for policy and stability in Central Asia Smith, Shane A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3204 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS LEADERSHIP TRANSITION IN KAZAKHSTAN AND UZBEKISTAN: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND STABILITY IN CENTRAL ASIA by Shane A. Smith September 2007 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Second Reader: James A. Russell Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED September 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Leadership Transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Implications for Policy and Stability in Central Asia 6. -

Isaacs 2009 Between

RADAR Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. No quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. You must obtain permission for any other use of this thesis. Copies of this thesis may not be sold or offered to anyone in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright owner(s). When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Isaacs, R. (2009). Between informal and formal politics : neopatrimonialism and party development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. PhD thesis. Oxford Brookes University. go/radar www.brookes.ac.uk/ Directorate of Learning Resources Between Informal and Formal Politics: Neopatrimonialism and Party Development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan Rico Isaacs Oxford Brookes University A Ph.D. thesis submitted to the School of Social Sciences and Law Oxford Brookes University, in partial fulfilment of the award of Doctor of Philosophy March 2009 98,218 Words Abstract This study is concerned with exploring the relationship between informal forms of political behaviour and relations and the development of formal institutions in post- Soviet Central Asian states as a way to explain the development of authoritarianism in the region. It moves the debate on from current scholarship which places primacy on either formal or informal politics in explaining modern political development in Central Asia, by examining the relationship between the two. -

The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan

Forschungsstelle Osteuropa Bremen Arbeitspapiere und Materialien No. 107 – March 2010 The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. A Background Study By Andreas Heinrich Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen Klagenfurter Straße 3, 28359 Bremen, Germany phone +49 421 218-69601, fax +49 421 218-69607 http://www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Arbeitspapiere und Materialien – Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen No. 107: Andreas Heinrich The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. A Background Study March 2010 ISSN: 1616-7384 About the author: Andreas Heinrich is a researcher at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen. This working paper has been produced within the research project ‘The Energy Sector and the Political Stability of Regimes in the Caspian Area: A Comparison of Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan’, which is being conducted by the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen from April 2009 until April 2011 with financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation. Language editing: Hilary Abuhove Style editing: Judith Janiszewski Layout: Matthias Neumann Cover based on a work of art by Nicholas Bodde Opinions expressed in publications of the Research Centre for East European Studies are solely those of the authors. This publication may not be reprinted or otherwise reproduced—entirely or in part—without prior consent of the Research Centre for East European Studies or without giving credit to author and source. © 2010 by Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Bremen Forschungsstelle Osteuropa Publikationsreferat Klagenfurter Str. 3 28359 Bremen – Germany phone: +49 421 218-69601 fax: +49 421 218-69607 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................5 1. -

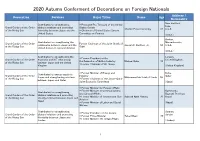

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals Address / Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age Nationality New Hartford, Contributed to strengthening * President Pro Tempore of the United Iowa, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting States Senate Charles Ernest Grassley 87 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun friendship between Japan and the * Chairman of United States Senate United States Committee on Finance (U.S.A.) Boston, Contributed to strengthening the Massachusetts, Grand Cordon of the Order Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of relationship between Japan and the Joseph F. Dunford Jr. 64 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun Staff United States on national defense (U.S.A.) Contributed to strengthening the London, * Former President of the Grand Cordon of the Order economic and ICT relationship United Kingdom Confederation of British Industry Michael Rake 72 of the Rising Sun between Japan and the United * Former Chairman of BT Group Kingdom (United Kingdom) * Former Minister of Energy and Doha, Contributed to energy supply to Grand Cordon of the Order Industry Qatar Japan and strengthening relations Mohammed bin Saleh Al Sada 59 of the Rising Sun * Former Chairman of the Japan-Qatar between Japan and Qatar Joint Economic Committee (Qatar) * Former Minister for Foreign Affairs * Former Minister of Communications Kathmandu, Contributed to strengthening and General Affairs Bagmati Province, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting * Former Minister of Tourism and Civil Ramesh Nath Pandey 76 Nepal of -

Download (2120Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/81134 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications University of Warwick Politics and International Studies Department Living on the Edge: Relocating Kazakhstan on the Margins of Power Davinia Hoggarth A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Philosophy in Politics and International Studies Submitted September 2015 II I Contents Acknowledgements V Declarations VII Abstract VIII Abbreviations IX Introduction 1 The Birth of ‘Central Asia’ 5 Classical Geopolitics and the Great Game 10 Structure and Scope of the Thesis 20 Chapter 1 – Methodology 28 Theory versus Practise 34 Chapter 2 – Literature Review 41 Geopolitics and Marginality 42 Strategic Culture 58 Central Asia 66 Chapter 3 – Eurasia: Marginal States and Great Powers 81 Entanglement of Security, Grand Strategy and Energy 85 Competing Eurasianisms 94 Energy as Foreign Policy and Strategy in Kazakhstan 108 Chapter 4 – Kazakhstan: Oil and Governance 114 Introduction to Kazakh Energy industry 117 Explaining KMGs Strategy and Performance 123 Relationship between Government -

The Formal Political System in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. a Background Study

www.ssoar.info The formal political system in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan: a background study Heinrich, Andreas Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Heinrich, A. (2010). The formal political system in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan: a background study. (Arbeitspapiere und Materialien / Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen, 107). Bremen: Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universität Bremen. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-441356 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Kazakhstan Nuclear Chronology

Kazakhstan Nuclear Chronology 2010 | 2009-2000 | 1999-1990 Last update: August 2010 This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2010 16 June 2010 It was announced that plans for a joint uranium enrichment center (UEC) between Kazakhstan and Russia located at the Angarsk Electro-Chemical Combine were dropped due to lack of economic feasibility. Reportedly, Kazakhstan may instead buy shares in one of Russia's four already operating enrichment centers. The UEC is separate from the international uranium enrichment center (IUEC) already operating in Angarsk. IUEC, created with the IAEA's approval, is meant to provide uranium enrichment for civilian purposes to states party to the NPT. Kazakhstan and Russia are already partners at the IUEC, with Rosatom owning 90%. Ukraine and Armenia are expected to join the project. — Judith Perera, "Change of plan on Kazakh uranium enrichment," McCloskey Nuclear Business, 16 June 2010. -

What Are the Heads of Central Asian Governments Remembered For?

What are the Heads of Central Asian Governments Remembered For? The countries of Central Asia gained independence at about the same time, however, their further political history developed independently. In a comparative analysis, one can see the similarities and differences in the state structure, as well as in how the prime ministers of the Central Asian countries were appointed, resigned, and what they were remembered for. Follow us on LinkedIn Since gaining independence, eleven prime ministers have replaced each other in Kazakhstan. Their subsequent political careers developed in different ways. While some subsequently moved even further in political or business circles, others, apparently, were disappointed in big-league politics and left it forever. For example, one of the former prime ministers was later elected to the presidency, and two more went into business after their resignation and are now on the Forbes list. Conversely, for some, things went downhill, for example, one left politics, another went into opposition and is hiding abroad, and another was convicted of corruption crimes and was removed from office. Let us take a closer look at each case, in chronological order. Kyrgyzstan Kyrgyzstan holds a record in the post-Soviet space for the change of heads of government. For 29 years of independence, 23 prime ministers have changed in Kyrgyzstan, not counting temporary appointments, and acting prime minister. What are they remembered for, and how did they leave their posts? What are the Heads of Central Asian Governments Remembered For? Tajikistan In 1994, a presidential form of government was adopted in Tajikistan. According to the new constitution, the government is headed by the president, where the prime minister has limited powers. -

The Curious World of Donald Trump's Private Russian Connections

Russia & The West The Curious World of Donald Trump’s Private Russian Connections James S. Henry Did the American people really know they were putting such a “well-connected” guy in the White House? Throughout Donald Trump’s presidential campaign he expressed glowing admiration for Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Many of Trump’s adoring comments were utterly gratuitous. After his Electoral College victory, Trump continued praising the former head of the KGB while dismissing the findings of all 17 American national security agencies that Putin directed Russian government interference to help Trump in the 2016 American presidential election. As veteran investigative economist and journalist Jim Henry shows below, a robust public record helps explain the fealty of Trump and his family to this murderous autocrat and the network of Russian oligarchs. Putin and his billionaire friends have plundered the wealth of their own people. They have also run numerous schemes to defraud governments and investors in the United States and Europe. From public records, using his renowned analytical skills, Henry shows what the mainstream news media in the United States have failed to report in any meaningful way: For three decades Donald Trump has profited from his connections to the Russian oligarchs, whose own fortunes depend on their continued fealty to Putin.We don’t know the full relationship between Donald Trump, the Trump family and their enterprises with the network of world-class criminals known as the Russian oligarchs. Henry acknowledges that his article poses more questions than answers, establishes more connections than full explanations. But what Henry does show should prompt every American to rise up in defense of their country to demand a thorough, out-in-the-open congressional investigation with no holds barred. -

Universitymgimo

Education For a Global FuturE UNIVERSITYMGIMO moscow statE institutE oF intErnational rElations intErnational rElations arEa studiEs Economics lEGal STUDIEs Political sciEncE manaGEmEnt Journalism Public rElations EnvironmEntal manaGEmEnt tradE, markEtinG and rEtail businEss statE and Public administration UNIVERSITYMGIMO FROM GLORY TO SUCCESS Nowadays MGIMO is a dynamic university, characterized by a strong international identity, spirit of innovation and global goals. Over its 70-year history, it went from a ‘‘diplomatic school‘‘ to a worldwide recognized university that is able to meet the most ambitious educational and research challenges. Its renomme is supported by Nhigh positions in university and think tanks rankings. Even the Guinness Book of World Records acknowledged MGIMO for the most languages taught – 53 actual languages. Every academic year sees more than 6,000 students with nearly 1,000 of them coming from abroad to study in MGIMO. The range of academic disciplines is constantly expanding as new departments and programs are launched each year. With the experience we have gained, we are always developing – successfully enhancing our cooperation with leading universities around the world. Our alumni community comprises more than 45,000 graduates with brilliant careers in both public and private sectors. anatoly torkunov Rector of MGIMO University Full Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences MGIMO Graduate 1972 MGIMO UNIVERSITY WHY MGIMO? TEN REASONS FOR MGIMO russia’s PrEmiEr univErsitY trulY intERNATIONAL GLOBAL rECOGnition widE COURSE sElEction OUTSTANDING ACADEmic ACCEss WORLD rENOWNEd rEsEarcH INNOVATIVE EDUCATION ACADEmic EXcEllEncE WORLDWIDE nETWORKING GrEAT social liFE MGIMO is Russia’s most prestigious educa- double-degree programs, offered in partner- tional institution for young people with inter- ship with a wide range of universities from national interests.