VICI 2003 Detailed Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Kaiser Permanente-Authored Publications Alphabetical by Author

2013 Kaiser Permanente-Authored Publications Alphabetical by Author 1. Abbas MA, Cannom RR, Chiu VY, Burchette RJ, Radner GW, Haigh PI, Etzioni DA Triage of patients with acute diverticulitis: are some inpatients candidates for outpatient treatment? Colorectal Dis. 2013 Apr;15(4):451-7. Southern California 23061533 KP author(s): Abbas, Maher A; Chiu, Vicki Y; Burchette, Raoul J; Radner, Gary W; Haigh, Philip I 2. Abbass MA, Slezak JM, DiFronzo LA Predictors of Early Postoperative Outcomes in 375 Consecutive Hepatectomies: A Single- institution Experience Am Surg. 2013 Oct;79(10):961-7. Southern California 24160779 KP author(s): Abbass, Mohammad Ali; Slezak, Jeffrey M; DiFronzo, Andrew L 3. Abbenhardt C, Poole EM, Kulmacz RJ, Xiao L, Curtin K, Galbraith RL, Duggan D, Hsu L, Makar KW, Caan BJ, Koepl L, Owen RW, Scherer D, Carlson CS, Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) and CCFR, Potter JD, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM Phospholipase A2G1B polymorphisms and risk of colorectal neoplasia Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013 Sep 12;4(3):140-9. Northern California 24046806 KP author(s): Caan, Bette 4. Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA Primary Care Guidelines for the Management of Persons Infected With HIV: 2013 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Nov 13. Mid-Atlantic 24235263 KP author(s): Horberg, Michael 5. Abraham AG, D'Souza G, Jing Y, Gange SJ, Sterling TR, Silverberg MJ, Saag MS, Rourke SB, Rachlis A, Napravnik S, Moore RD, Klein MB, Kitahata MM, Kirk GD, Hogg RS, Hessol NA, Goedert JJ, Gill MJ, Gebo KA, Eron JJ, Engels EA, Dubrow R, Crane HM, Brooks JT, Bosch RJ, Strickler HD, North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of IeDEA Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women: A North American multi-cohort collaboration prospective study J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. -

World Ratings Draughts

FMJD Rating No 83 January/March 2015 FMJD rating Nr 83 January 2015 email: [email protected] 1 FMJD Rating No 83 January/March 2015 With any question concerning this issue You can contact me directly via email: [email protected] 2 FMJD Rating No 83 January/March 2015 1. Rating - open Name Nationality Title Rating +/- 1 = shvartsman alexander Russia gmi 2425 -19 2 = georgiev alexander Russia gmi 2421 -15 3 +5 chizhov alexey Russia gmi 2409 +18 4 = getmanski alexander Russia gmi 2404 +4 5 +1 boomstra roel Netherlands gmi 2399 +4 6 -3 baliakin alexander Netherlands gmi 2396 -11 7 = gantvarg anatoli Belarus gmi 2393 +1 8 -3 valneris guntis Latvia gmi 2388 -9 9 +2 prosman erno Netherlands gmi 2378 +2 10 +2 dolfing martin Netherlands gmi 2377 +3 11 +3 shaibakov ainur Russia gmi 2373 +6 12 -2 virny vadim Germany gmi 2370 -7 13 +3 amrillaev murodullo Russia gmi 2367 +3 14 -5 meurs pim Netherlands gmi 2364 -16 15 = clerc rob Netherlands gmi 2363 -3 16 -3 ivanov artem Ukraine mi 2361 -11 17 +2 cordier arnaud France gmi 2358 +7 18 -1 ndjofang jean marc Cameroon gmi 2357 +4 19 +3 heusdens ron Netherlands gmi 2351 +3 20 +4 jansen gerard Netherlands gmi 2348 +3 21 +7 kalmakov andrej Russia gmi 2346 +5 22 +1 vermin hans Switzerland gmi 2346 = 23 -2 n'diaye macodou Senegal gmi 2344 -5 24 +5 anikeev yuriy Ukraine gmi 2343 +5 25 -7 krajenbrink johan Netherlands gmi 2341 -11 26 +1 van den akker jeroen Netherlands gmi 2339 -3 27 +3 leesmann kaido Estonia gmi 2337 = 28 +3 misans roberts Latvia mi 2336 = 29 +3 kolesov gawril Russia mi 2334 = 30 -4 vatutin evgeni -

Lisa Strother Phd Thesis

INVESTIGATION OF MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR MECHANISMS UNDERPINNING THE NEUROTOXICITY OF HOMOCYSTEINE AND ITS METABOLITES IN MODELS OF NEURODEGENERATION Lisa Strother A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/17067 This item is protected by original copyright Investigation of molecular and cellular mechanisms underpinning the neurotoxicity of homocysteine and its metabolites in models of neurodegeneration Lisa Strother CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. xii DECLARATIONS .................................................................................................................. xiv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................ xvii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ....................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 1.1.1 Homocysteine -

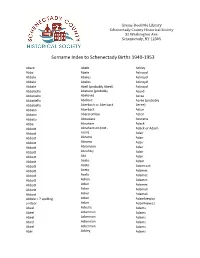

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. -

Testicular Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma—Clinical, Molecular, and Immunological Features

cancers Review Testicular Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma—Clinical, Molecular, and Immunological Features Marjukka Pollari 1,2,* , Suvi-Katri Leivonen 1,3 and Sirpa Leppä 1,3 1 Research Program Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland; suvi-katri.leivonen@helsinki.fi (S.-K.L.); sirpa.leppa@helsinki.fi (S.L.) 2 Department of Oncology, Tays Cancer Center, Tampere University Hospital, 33521 Tampere, Finland 3 Department of Oncology, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Helsinki University Hospital, 00029 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: marjukka.pollari@pshp.fi Simple Summary: Testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (T-DLBCL) is a rare and aggressive lymphoma entity that mainly affects elderly men. It has a high relapse rate with especially the relapses of the central nervous system associating with dismal outcome. T-DLBCL has a unique biology with distinct genetic characteristics and clinical presentation, and the increasing knowledge on the tumor microenvironment of T-DLBCL highlights the significance of the host immunity and immune escape in this rare lymphoma, presenting in an immune-privileged site of the testis. This review provides an update on the latest progress made in T-DLBCL research and summarizes the clinical perspectives in T-DLBCL. Abstract: Primary testicular lymphoma is a rare lymphoma entity, yet it is the most common testicular malignancy among elderly men. The majority of the cases represent non-germinal center B-cell- Citation: Pollari, M.; Leivonen, S.-K.; like (non-GCB) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with aggressive clinical behavior and a Leppä, S. Testicular Diffuse Large relatively high relapse rate. Due to the rareness of the disease, no randomized clinical trials have been B-Cell Lymphoma—Clinical, conducted and the currently recognized standard of care is based on retrospective analyses and few Molecular, and Immunological phase II trials. -

Acta Okl1-2014.Cdr

ACTA POLONIAE PHARMACEUTICA VOL. 72 No. 1 January/February 2015 ISSN 2353-5288 Drug Research EDITOR Aleksander P. Mazurek National Medicines Institute, The Medical University of Warsaw ASSISTANT EDITOR Jacek Bojarski Medical College, Jagiellonian University, KrakÛw EXECUTIVE EDITORIAL BOARD Miros≥awa Furmanowa The Medical University of Warsaw Boøenna Gutkowska The Medical University of Warsaw Roman Kaliszan The Medical University of GdaÒsk Jan Pachecka The Medical University of Warsaw Jan Pawlaczyk K. Marcinkowski University of Medical Sciences, PoznaÒ Janusz Pluta The Medical University of Wroc≥aw Witold Wieniawski Polish Pharmaceutical Society, Warsaw Pavel Komarek Czech Pharmaceutical Society Henry Ostrowski-Meissner Charles Sturt University, Sydney Erhard Rˆder Pharmazeutisches Institut der Universit‰t, Bonn Phil Skolnick DOV Pharmaceutical, Inc. Zolt·n Vincze Semmelweis University of Medicine, Budapest This Journal is published bimonthly by the Polish Pharmaceutical Society (Issued since 1937) The paper version of the Publisher magazine is a prime version. The electronic version can be found in the Internet on page www.actapoloniaepharmaceutica.pl An access to the journal in its electronics version is free of charge Impact factor (2013): 0.693 MNiSW score (2013): 15 points Index Copernicus (2012): 13.18 Charges Annual subscription rate for 2014 is US $ 210 including postage and handling charges. Prices subject to change. Back issues of previously published volumes are available directly from Polish Pharmaceutical Society, 16 D≥uga St., 00-238 Warsaw, Poland. Payment should be made either by bankerís draft (money order) issued to ÑPTFarmî or to our account Millennium S.A. No. 29 1160 2202 0000 0000 2770 0281, Polskie Towarzystwo Farmaceutyczne, ul. -

Investigation of the Role of T and B Cells in a Novel Humanized Mouse Model for Systemic Sclerosis

Aus dem Forschungszentrum Borstel Leibniz Lungenzentrum Direktor: Prof. Dr. Stefan Ehlers und der Universität zu Lübeck Klinik für Rheumatologie Direktorin: Prof. Dr. Gabriela Riemekasten Investigation of the role of T and B cells in a novel humanized mouse model for systemic sclerosis Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Universität zu Lübeck - Sektion Medizin- submitted by Yaqing Shu from JiangXi, China Lübeck 2019 First referee: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Xinhua Yu Second referee: Prof. Dr. med. Peter König Date of oral examination: 15. 01. 2020 Approved for printing. Lübeck, den 15.01.2020 - Promotionskommission der Sektion Medizin - Table of Contents Zusammenfassung ........................................................................................................................... 1 Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviation ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1. Systemic sclerosis (SSc)........................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. Clinical features in SSc .......................................................................................................6 1.1.2. Immunological features -

Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation

Disclosure for 2012 under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996 Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation This category includes Hydro One Inc., Ontario Power Generation Inc. and their subsidiaries. Divulgation pour 2012 en vertu de la Loi de 1996 sur la divulgation des traitements dans le secteur public Hydro One et Ontario Power Generation Cette catégorie englobe Hydro One Inc., Ontario Power Generation Inc. et leurs filiales. Taxable Surname/Nom de Given Name/ Salary Paid/ Benefits/ Employer/Employeur famille Prénom Position/Poste Traitement Avant. impos. Hydro One ABBOTT BRAD Regional Maintainer - Lines Union Trades Supervisor 3$129,794.86 $1,403.37 Hydro One ABBOTT MARK Customer & Business Services Manager $128,716.44 $1,158.84 Hydro One ABRAMS DONALD Line Subforeperson Construction $103,529.82 $0.00 Hydro One ABUJAFAR MOHAMMAD Senior Protection & Control Engineer/Officer $104,748.38 $694.51 Hydro One ACTON ROB Controller $128,327.49 $1,446.58 Hydro One ADAM JOCELYNE Regional Maintainer II - Electrical $103,872.58 $1,783.47 Hydro One ADAMS CHAD Regional Maintainer II - Lines $117,823.68 $1,322.46 Hydro One ADAMS CLINT Area Forestry Technician $101,386.47 $1,358.13 Hydro One ADAMS DAN Regional Maintainer I - Lines $113,520.18 $1,354.65 Hydro One ADAMS DAVID Customer Care Director $185,590.96 $1,081.06 Hydro One ADAMS GREG Regional Maintainer - Lines Union Trades Supervisor 2$151,060.68 $1,458.18 Hydro One ADAMS STEPHEN Distribution Technician (Forestry) $117,624.13 $1,430.34 Hydro One ADLINGTON MIKE Regional Maintainer 1 - Electrical -

Modeling and Molecular Dynamics Indicate That Snake Venom Phospholipase B-Like Enzymes Are Ntn-Hydrolases T

Toxicon 153 (2018) 106–113 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Review Modeling and molecular dynamics indicate that snake venom phospholipase B-like enzymes are Ntn-hydrolases T ∗ Mônika Aparecida Coronadoa, ,1, Danilo da Silva Oliviera,1, Raphael Josef Eberlea, ∗∗ Marcos Serrou do Amaralb, Raghuvir Krishnaswamy Arnia, a Multiuser Center for Biomolecular Innovation, Department of Physics, Universidade Estadual Paulista, UNESP/Ibilce, São Jose do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil b Institute of Physics, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, MS, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Phospholipase-B-like (SVPLB-like) enzymes are present in relatively small amounts in a number of venoms, Snake venom phospholipase B however, their biological function and mechanisms of action are un-clear. A three-dimensional model of the Crotalus adamanteus SVPLB-like enzyme from Crotalus adamanteus was generated by homology modeling based on the crystal Ntn-hydrolase structures of bovine Ntn-hydrolyases and the modeled protein possesses conserved domains characteristic of Molecular modeling Ntn-hydrolases. Molecular dynamics simulations indicate that activation by autocatalytic cleavage results in the Molecular dynamics removal of 25 amino acids which increases accessibility to the active site. SVPLB-like enzymes possess a highly reactive cysteine and are hence amidases that to belong to the N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolase family. The Ntn-hydrolases (N-terminal nucleophile) form a superfamily of diverse enzymes that are activated auto- catalytically; wherein the N-terminal catalytic nucleophile is implicated in the cleavage of the amide bond. 1. Introduction Ntn-hydrolases are post-translationally activated by an autocatalytic process that cleavages and liberates a peptide of 25 amino acids. -

HOUSEWORK News from Transition House • Santa Barbara, California • Fall 2012

HOUSEWORK news from transition house • santa barbara, california • fall 2012 Mom’s Brings Families Home By Isabelle Walker ast spring, Abby Richards’ life L took a turn for the “normal.” After twelve months of living in motels, doubled up with relatives, and in Tran- sition House’s emergency shelter, she and her daughter moved into their own two-bedroom apartment in the Mom’s complex Transition House recently constructed next to its administration building. Ordinary things most Ameri- cans take for granted are a reality again for her. She has a job, and she’s cooking meals for herself and her daughter in their very own kitchen. “I had given up,” said Abby. “[I Mom’s apartments offer supportive housing and a new infant day care center. thought] I was going to have to find a family for my daughter [to live with].” barrier to either employment or hous- tion and computer systems, when her Then she found out she was eligible ing stability. Both the tax credits and daughter was born at age 39, juggling for one of the eight new units in the vouchers allow Transition House to work and parenting without the support Mom’s building. charge some residents on fixed incomes of a spouse led to financial problems. Eight families moved into the new very low rent. A brand new infant-care In 2009, she was laid off from her job. apartment building in May after a center, with double the capacity of the She lived off savings and credit cards, long planning and construction pro- former center, is also up and running then moved in with relatives. -

Biuletyn Polskiego Towarzystwa Jêzykoznawczego

BIULETYN POLSKIEGO TOWARZYSTWA JÊZYKOZNAWCZEGO BULLETIN DE LA SOCIÉTÉ POLONAISE DE LINGUISTIQUE ZESZYT LV – FASCICULE LV WYDAWNICTWO ENERGEIA KOMITET REDAKCYJNY Redaktor: Kazimierz Polañski Cz³onkowie: Andrzej Bogus³awski, Stanis³aw Karolak, Ruta Nagucka, Krystyna Pisarkowa, Aleksander Szulc Sekretarz: Krzysztof Kor¿yk ADRES REDAKCJI: al. Mickiewicza 9/11 31-120 Kraków e-mail: [email protected] Wydane z zasi³ku Komitetu Badañ Naukowych ISSN 0032-3802 © Copyright by Wydawnictwo Energeia Warszawa 2000 Wydawnictwo Energeia, skr. poczt. 43, 00-976 Warszawa Sk³ad: Wydawnictwo Energeia, Warszawa Druk: Drukarnia Matrix, Warszawa Printed in Poland SPIS RZECZY – TABLES DES MATIÈRES Artyku³y M. Tokarz (Katowice), Semantyka sytuacyjna a interpretacja wypowiedzi niedo- s³ownych .............................................................................................................. 5 J. Wajszczuk (Warszawa), Can a division of lexemes according to syntactic crite- ria be consistent?.................................................................................................. 19 K. Pisarkowa (Kraków), The reception of Bronis³aw Malinowskis work and the obligations of a linguist ....................................................................................... 39 J. Puzynina (Warszawa), Aleksander Brückner uczony i cz³owiek ................... 53 W. Wysoczañski (Wroc³aw), Ekologia jêzyka jako dyscyplina heterogenicznego opisu jêzyka ........................................................................................................ -

Sunday, July 25, 2021 Sunday, July 25, 2021

Program of the Meeting CALENDAR OF EVENTS * Presenting Author Sunday, July 25, 2021 Sunday, July 25, 2021 Council Symposium SAM Multi-Disciplinary Scientific Symposium 10:30 am - 11:30 am 10:30 am - 11:30 am -TRACK 1 -TRACK 4 SU-A-TRACK 1 International Council Symposium: AAPM SU-A-TRACK 4 Solid State PET in Radiology and Global Engagement; Planning for the Future Radiation Oncology: from SiPM to AI in the Clinic Moderator: Ana Maria Marques da Silva, Pontifica Universidade Moderator: Jun Zhang, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Catolica do RS, Porto Alegre, RS 10:30 am J. Zhang, The Ohio State University: Technologies and AI 10:30 am S. Avery, University of Pennsylvania: Global Medical Features of SiPM PET Instrumentation Physics Education and Training 10:55 am S. Bowen, University of Washington, School of Medicine: 10:38 am S. Parker, Wake Forest Baptist Health High Point Medical Clinical Considerations of SiPM PET in Radiology and Center: Global Need Assessment Radiation Oncology 10:46 am J. Palta, Virginia Commonwealth University: Global 11:20 am Q&A & Panel Discussion Collaborations 10:54 am R. Jeraj, University of Wisconsin: Global Research and SAM Therapy Scientific Symposium Scientific Innovation 10:30 am - 12:30 pm 11:02 am G. Kim, University of California, San Diego: Global Data and Information Exchange -TRACK 5 11:10 am S. Wadi-Ramahi, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: SU-AB-TRACK 5 Affordable Cancer Care for All Global Clinical Education and Training Moderator: Laurence Edward Court, University of Texas MD 11:18 am Q&A Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 10:30 am Introduction Students and Trainees 10:33 am C.