Western Balkans Policy Review 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability

Department of Political and Social Sciences Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability Igor Guardiancich Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, October 2009 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of Political and Social Sciences Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, Implementation and Sustainability Igor Guardiancich Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Martin Rhodes, University of Denver/formerly EUI (Supervisor) Prof. Nicholas Barr, London School of Economics Prof. Martin Kohli, European University Institute Prof. Tine Stanovnik, Univerza v Ljubljani © 2009, Igor Guardiancich No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Guardiancich, Igor (2009), Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, implementation and sustainability European University Institute DOI: 10.2870/1700 Guardiancich, Igor (2009), Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Legislation, implementation and sustainability European University Institute DOI: 10.2870/1700 Acknowledgments No PhD dissertation is a truly individual endeavour and this one is no exception to the rule. Rather it is a collective effort that I managed with the help of a number of people, mostly connected with the EUI community, to whom I owe a huge debt of gratitude. In particular, I would like to thank all my interviewees, my supervisors Prof. Martin Rhodes and Prof. Martin Kohli, as well as Prof. Tine Stanovnik for continuing intellectual support and invaluable input to the thesis. -

Montenegro Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Montenegro Country Report Status Index 1-10 7.50 # 22 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 7.90 # 23 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 7.11 # 28 of 129 Management Index 1-10 6.51 # 18 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Montenegro Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Montenegro 2 Key Indicators Population M 0.6 HDI 0.791 GDP p.c. $ 14206.2 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.1 HDI rank of 187 52 Gini Index 28.6 Life expectancy years 74.5 UN Education Index 0.838 Poverty3 % 0.0 Urban population % 63.5 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 163.1 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Preparations for EU accession have dominated the political agenda in Montenegro during the period under review. Recognizing the progress made by the country on seven key priorities identified in its 2010 opinion, the European Commission in October 2011 proposed to start accession negotiations. -

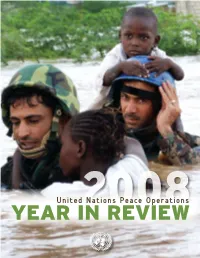

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

News in Brief 12 July

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe OSCE Mission to Croatia News in brief 12 July – 25 July 2006 Prime Minister Sanader visits Serbia On 21 July, Croatian Prime Minister Ivo Sanader paid his second official visit to Serbia, further intensifying bilateral relations between the two countries. Prime Minister Sanader made his first visit to Belgrade in November 2004, followed by a reciprocal visit to Zagreb by Serbian Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica in November 2005. Prior to their meeting in Belgrade the two Prime Ministers officially opened the newly renovated border crossing between Croatia and Serbia in Bajakovo, Eastern Croatia. At the ceremony attended by representatives of both governments and the diplomatic corps from Zagreb and Belgrade, the Croatian Premier said that "today we are opening the future of new relations between our two countries." Echoing this sentiment, Prime Minister Koštunica added that both the "Serbian and Croatian governments will work to heal wounds from the past and build a new future for the two states in a united Europe". Later, following talks in Belgrade, both Prime Ministers declared that Serbia and Croatia have a joint objective, to join the European Union, and that strong bilateral relations between the two countries should be the foundation of political security in the region. Prime Minister Sanader commended the efforts both governments had made towards improving the position of minorities in line with the bilateral agreement on minority protection signed between the two countries in November 2004. He went on to stress his cabinet’s wish to see the Serb minority fully integrated into Croatian society. -

A European Montenegro How Are Historical Monuments Politically Instrumentalised in Light of Future Membership of the European Union?

A European Montenegro How are historical monuments politically instrumentalised in light of future membership of the European Union? MA Thesis in European Studies Graduate School for Humanities Universiteit van Amsterdam Daniel Spiers 12395757 Main Supervisor: Dr. Nevenka Tromp Second Supervisor: Dr. Alex Drace-Francis December, 2020 Word Count: 17,660 Acknowledgments My time at the Universiteit van Amsterdam has been a true learning curve and this paper is only a part of my academic development here. I wish to express my gratitude to all the lecturing staff that I have had contact with during my studies, all of whom have all helped me mature and grow. In particular, I want to thank Dr. Nevenka Tromp who has been a fantastic mentor to me during my time at the UvA. She has consistently supported my academic aims and has been there for me when I have had concerns. Lastly, I want to thank the family and friends in my life. My parents, sister and grandparents have always supported me in my development, and I miss them all dearly. I show appreciation to the friends in my life, in Amsterdam, London, Brussels and Montenegro, who are aware of my passion for Montenegro and have supported me at every stage. Dedication I dedicate this thesis to the people of Montenegro who have lived through an extraordinary period of change and especially to those who believe that it is leading them to a brighter future. Abstract This thesis seeks to explore how historical monuments are politically instrumentalised in Montenegro in light of future membership of the European Union. -

I. Diplomacy's Winding Course 2012

2012 - A Make or Break Year for Serbia and Kosovo? By Dr. Matthew Rhodes and Dr. Valbona Zeneli nstead of the hoped for turn to normalization, 2011 NATO and EU member states except Cyprus, Greece, Isaw escalated tensions over Kosovo. Agreement Romania, Slovakia, and Spain. on Kosovo’s participation in regional fora and Serbia’s formal advance to Serbia’s challenge before EU candidacy in early 2012 the International Court of have revived a cautious “The very active first three Justice (ICJ) marked the centerpiece of its strategy sense of optimism, but months of 2012 have restored unresolved underlying issues against Kosovo’s move. and approaching political a sense of calm regarding Winning support within the United Nations General contests leave the prospects Serbia and Kosovo. Intensified for further progress uncertain. Assembly in October 2008 Warnings of precipices and European and American for consideration of the case powder kegs are overdone represented a significant in the Balkans, but 2012 is diplomacy together with success for Serbian diplomacy. shaping up as a potentially leaders’ attention to larger However, the Court’s July decisive year for international 2010 decision that Kosovo’s policy in the region. goals prevented 2011’s act had not violated international law effectively skirmishes over border Despite the Euro-Atlantic closed off this challenge. community’s current internal posts and barricades from Potentially positively for both challenges, integration into sides, however, the case’s that community’s formal escalating into something conclusion opened the way structures remains the best worse. As welcome as that for direct talks on technical path for Balkan security issues between Belgrade and and development. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ...z w ~ ~ ~ w C ..... Z w ~ oQ. -'w >w Public Disclosure Authorized C -' -ct ou V') Public Disclosure Authorized " Public Disclosure Authorized VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Critical Dimension of Development Background 2 Agenda 4 Participant Biographies 10 Photo Contest Imagining Peace 32 Photo Contest Winners 33 Photo Contest Finalists 36 Conference Organizing Team & Contact Information 43 The Conflict, Crime and Violence team in the Social high levels of violent crime, street violence, do Development Department (SDV) has organized a mestic violence, and other kinds of violence. day and a half event focusing on "Violence Pre vention: A Critical Dimension of Development". Violence takes many forms: from the traditional As the issue of violence crosscuts other agendas protection racket by illegal organizations to the of the World Bank, the objectives of the event are rise of international illegal trafficking (arms, hu to raise World Bank staff's awareness of the link mans, drugs), from gang-based urban violence between violence prevention and development, its and crime to politically-motivated violence fueled relevance for development, and to present the ra by socio-economic grievances. All these forms of tionale for increased attention to violence preven violence concur to erode the well-being of all- and tion and reduction within World Bank operations. more acutely of the poorest - and to stymie devel opment efforts. Social failure, weak institutional Violence has become one of the most salient de capacity and the lack of a legal framework to pro velopmental issues in the global agenda. Its nega tect and guarantee people's safety and rights cre tive impact on social and economic development ate a climate of lawlessness and engender dynam in countries across the world has been well doc ics of state-within-state behavior by increasingly umented. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Chapitre 0.Indd

Crosswalking EUR-Lex Crosswalking OA-78-07-319-EN-C OA-78-07-319-EN-C Michael Düro Michael Düro Crosswalking EUR-Lex: Crosswalking EUR-Lex: a proposal for a metadata mapping a proposal for a metadata mapping to improve access to EU documents : to improve access to EU documents a proposal for a metadata mapping to improve access to EU documents to access improve mapping to a metadata for a proposal The Oce for Ocial Publications of the European Michael Düro has a background The Oce for Ocial Publications of Communities oers direct free access to the most complete in information science, earned a Masters the European Communities collection of European Union law via the EUR-Lex online in European legal studies and works in is the publishing house of the institu- database. the EUR-Lex unit of the Oce for Ocial tions, agencies and other bodies of the Publications of the European The value of the system lies in the extensive sets of metadata European Union. Communities. which allow for ecient and detailed search options. He was awarded the The Publications Oce produces and Nevertheless, the European institutions have each set up Dr. Eduard-Martin-Preis for outstanding distributes the Ocial Journal of the their own document register including their own sets of research in 2008 by the University of European Union and manages the metadata, in order to improve access to their documents and Saarland, Germany, for this thesis. EUR-Lex website, which provides direct meet the increasing need for transparency. free access to European Union law. -

Qarku Shkodër Zgjedhje Për Organet E Qeverisjes Vendore 2019

Zgjedhje për Organet e Qeverisjes Vendore 2019 Komisionet e Zonave të Administrimit Zgjedhor (KZAZ) Qarku Shkodër KZAZ Nr.1 Adresa: Koplik Qendër, Qendra Kulturore e Femijeve Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Sabrije Çelaj PS Zv.Kryetare Kujtim Lamthi PS Anëtar Neriban Hoxhaj PS Anëtar Eristjon Smajlaj Anëtar Kryesisht Rexhina Rrjolli PS Sekretare Nr.Tel 675651530 Email [email protected] KZAZ Nr.2 Adresa: Shkodër, Pallati i Sportit "Qazim Dervishi" Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Gazmir Jahiqi PS Kryetar Fatbardh Dama PS Anëtar Servete Osja PS Anëtare Erion Mandi PS Anëtar Agim Martini Sekretar Kryesisht Nr.Tel 695234514 Email [email protected] KZAZ Nr.3 Adresa: Shkodër, Palestra e Shkolles "Ismail Qemali" Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Fatjon Tahiri PS Zv.Kryetar Eltjon Boshti PS Anëtar Edita Shoshi PS Anëtare Isida Ramja Anëtar Kryesisht Arbër Jubica PS Sekretar Nr.Tel 692098232 Email [email protected] KZAZ Nr.4 Adresa: Shkodër, Shkolla 9-vjeçare "Azem Hajdari" Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Valbona Tula PS Kryetare Antonio Matia PS Anëtar Ermal Vukaj PS Anëtar Irisa Ymeri PS Anëtar Alban Bala Sekretar Kryesisht Nr.Tel 676503720 Email [email protected] KZAZ Nr.5 Adresa: Shkodër, Shkolla 9-vjeçare "Xheladin Fishta" Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Ermira Ymeraj PS Zv.Kryetare Luçian Pjetri PS Anëtar Valentin Nikolli PS Anëtar Pashko Ara Anëtar Kryesisht Ilir Dibra PS Sekretar Nr.Tel 674634258 Email [email protected] KZAZ Nr.6 Adresa: Bushat, Shkolla e mesme profesionale "Ndre Mjeda" Emri Mbiemri Subjekti Pozicioni Sokol Shkreli PS Kryetar -

A Balkanist in Daghestan: Annotated Notes from the Field Victor A

A Balkanist in Daghestan: Annotated Notes from the Field Victor a. Friedman University of Chicago Introduction and Disclaimer The Republic of Daghestan has received very little attention in the West. Chenciner (1997) is the only full-length account in English based on first-hand visits mostly in the late 1980's and early 1990's. Wixman's (1980) excellent study had to be based entirely on secondary sources, and Bennigsen and Wimbush (1986:146-81 et passim), while quite useful, is basically encyclopedic and somewhat dated. Since Daghestan is still difficult to get to, potentially unstable, and only infrequently visited by Western scholars (mostly linguists), I am offering this account of my recent visit there (16-20 June 1998), modestly supplemented by some published materials. My intent is basically informative and impressionistic, and I do not attempt to give complete coverage to many topics worthy of further research. This account does, however, update some items covered in the aforementioned works and makes some observations on Daghestan with respect to language, identity, the political situation, and a comparison with the another unstable, multi-ethnic, identity construction site, i.e., Balkans, particularly Macedonia. Background Daghestan is the third most populous Republic in the Russian Federation (after Bashkortostan and Tatarstan; Osmanov 1986:24). The northern half of its current territory, consisting of the Nogai steppe and the Kizljar region settled in part by Terek Cossacks, was added in 1922, after the fall of the North Caucasian -

BALKANS-Eastern Europe

Page 16-BALKANS Name: __________________________ BALKANS-Eastern Europe WHAT ARE THE BALKANS??? World Book Online—Type in the word “BALKANS” in the search box, it is the first link that comes up. Read the first paragraph. The Balkans are ____________________________________________________________________________. “Balkan” is a word that means- _______________________________________________________. Why are the Balkans often called the “Powder Keg of Europe”:? Explain: ________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ On the right-side of the page is a Map-Balkan Peninsula Map---click on the map. When you have the map open, look and study it very carefully: How many countries are located in the Balkans (country names are in all bold-face): ______________ List the countries located in the Balkans today: _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ _______________________ ___________________________ ________________________ Go back to World Book Online search box: type in Yugoslavia---click on the 1st link that appears. Read the 1st paragraph. Yugoslavia was a _______________________________________________________. Click on the map on the right---Yugoslavia from 1946 to 2003. Look/study in carefully. Everything in orange AND yellow was a part of Yugoslavia from _____________ to __________________. Everything in light yellow was also a part of Yugoslavia from ____________ to ________________. So the big issue/question then is what happened to the country of Yugoslavia starting in 1991, through 2003 when the country of Yugoslavia ceases to exist. The video (and questions) on the back will help explain the HORRIFIC break-up of Yugoslavia and what really happened—and why it is still a VERY volatile region of the world even today. Page 16-BALKANS Name: __________________________ Terror in the Balkans: Breakup of Yugoslavia 1.