Virginia Rail Rallus Limicola Being a Secretive Marsh Bird, the Virginia Rail Is Dif- Ficult to Observe and Census Accurately

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecrex Restudied: a Small Eocene Guineafowl

TELECREX RESTUDIED: A SMALL EOCENE GUINEAFOWL STORRS L. OLSON In reviewing a number of the fossil species presently placed in the Rallidae, I have had occasion to examine the unique type-an incomplete femur-of Telecrex grangeri Wetmore (1934)) described from the Upper Eocene (Irdin Manha Formation) at Chimney Butte, Shara Murun region, Inner Mongolia. Although Wetmore assigned this fossil to the Rallidae, he felt that the species was distinct enough to be placed in a separate subfamily (Telecrecinae) ; this he considered to be ancestral to the modern Rallinae. After apparently ex- amining the type, Cracraft (1973b:17) assessed it as “decidedly raillike in the shape of the bone but distinct in the antero-posterior flattening of the head and shaft.” However, he suggested that Wetmores’ conclusions about its relationships to the Rallinae would have to be re-evaluated. Actually, Tele- crex bears very little resemblance to rails, and the distinctive proximal flat- tening of the shaft (but not of the head, contra Cracraft) is a feature peculiar to certain of the Galliformes. Further, my comparisons show Telecrex to be closest to the guineafowls (Numididae), a family hitherto known only from Africa and Europe. DISCUSSION The type specimen of Telecrex grangeri (AMNH 2942) is a right femur, lacking the distal end and part of the trochanter (Fig. 1). Its measurements are: proximal width 11.6 mm, depth of head 4.2, width of shaft at midpoint 4.6, depth of shaft at midpoint 4.1, overall length (as preserved ) 46.1. Telecrex differs from all rails -

South Africa Rallid Quest 15Th to 23Rd February 2019 (9 Days)

South Africa Rallid Quest 15th to 23rd February 2019 (9 days) Buff-spotted Flufftail by Adam Riley RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 2 Never before in birding history has a trip been offered as unique and exotic as this Rallid Quest through Southern Africa. This exhilarating birding adventure targets every possible rallid and flufftail in the Southern African region! Included in this spectacular list of Crakes, Rails, Quails and Flufftails are near-mythical species such as Striped Crake, White-winged, Streaky-breasted, Chestnut-headed and Striped Flufftails and Blue Quail, along with a supporting cast of Buff-spotted and Red-chested Flufftails, African, Baillon’s, Spotted and Corn Crakes, African Rail, Allen’s Gallinule, Lesser Moorhen and Black-rumped Buttonquail. As if these once-in-a-lifetime target rallids and rail-like species aren’t enough, we’ll also be on the lookout for a number of the region’s endemics and specialties, especially those species restricted to the miombo woodland, mushitu forest and dambos of Zimbabwe and Zambia such as Chaplin’s and Anchieta’s Barbet, Black-cheeked Lovebird, Bar-winged Weaver, Bocage’s Akalat, Ross’s Turaco and Locust Finch to mention just a few. THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE MAIN TOUR ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Johannesburg and drive to Dullstroom Day 2 Dullstroom area Day 3 Dullstroom to Pietermaritzburg via Wakkerstroom Day 4 Pietermaritzburg and surrounds Day 5 Pietermaritzburg to Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills Day 6 Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills Day 7 Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills to Johannesburg Day 8 Johannesburg to Zaagkuilsdrift via Marievale and Zonderwater Day 9 Zaagkuilsdrift to Johannesburg and departure RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 3 TOUR ROUTE MAP… RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 4 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Johannesburg and drive to Dullstroom. -

Houde2009chap64.Pdf

Cranes, rails, and allies (Gruiformes) Peter Houde of these features are subject to allometric scaling. Cranes Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Box 30001 are exceptional migrators. While most rails are generally MSC 3AF, Las Cruces, NM 88003-8001, USA ([email protected]) more sedentary, they are nevertheless good dispersers. Many have secondarily evolved P ightlessness aJ er col- onizing remote oceanic islands. Other members of the Abstract Grues are nonmigratory. 7 ey include the A nfoots and The cranes, rails, and allies (Order Gruiformes) form a mor- sungrebe (Heliornithidae), with three species in as many phologically eclectic group of bird families typifi ed by poor genera that are distributed pantropically and disjunctly. species diversity and disjunct distributions. Molecular data Finfoots are foot-propelled swimmers of rivers and lakes. indicate that Gruiformes is not a natural group, but that it 7 eir toes, like those of coots, are lobate rather than pal- includes a evolutionary clade of six “core gruiform” fam- mate. Adzebills (Aptornithidae) include two recently ilies (Suborder Grues) and a separate pair of closely related extinct species of P ightless, turkey-sized, rail-like birds families (Suborder Eurypygae). The basal split of Grues into from New Zealand. Other extant Grues resemble small rail-like and crane-like lineages (Ralloidea and Gruoidea, cranes or are morphologically intermediate between respectively) occurred sometime near the Mesozoic– cranes and rails, and are exclusively neotropical. 7 ey Cenozoic boundary (66 million years ago, Ma), possibly on include three species in one genus of forest-dwelling the southern continents. Interfamilial diversifi cation within trumpeters (Psophiidae) and the monotypic Limpkin each of the ralloids, gruoids, and Eurypygae occurred within (Aramidae) of both forested and open wetlands. -

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis Tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025 IUCN Bustard Specialist Group About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature- based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation was opened in October 2001 with the core support of the Spanish Ministry of Environment, the regional Government of Junta de Andalucía and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). The mission of IUCN-Med is to influence, encourage and assist Mediterranean societies to conserve and sustainably use natural resources in the region, working with IUCN members and cooperating with all those sharing the same objectives of IUCN. www.iucn.org/mediterranean About the IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of 9,000 experts. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced

ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced APPLICATION: STANDARDS: ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced is used as bare • B-230 Aluminum wire, 1350-H19 for Electrical Purposes overhead transmission cable and as primary and secondary • B-232 Aluminum Conductors, Concentric-Lay-Stranded, distribution cable. ACSR offers optimal strength for line design. Coated Steel Reinforced (ACSR) BARE ALUMINUM Variable steel core stranding for desired strength to be achieved • B-341 Aluminum-Coated Steel Core Wire for Aluminum without sacrificing ampacity. Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR/AZ) • B-498 Zinc-Coated Steel Core Wire for Aluminum CONDUCTORS: Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR) • B-500 Metallic Coated Stranded Steel Core for Aluminum • Aluminum alloy 1350-H119 wires, concentrically stranded Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR) around a steel core available with Class A, B or C galvanizing; • RUS Accepted aluminum coated (AZ); or aluminum-clad steel core (AL). Additional corrosion protection is available through the application of grease to the core or infusion of the complete cable with grease. Also available with Non Specular surface finish. Resistance** Diameter(inch) Weight (lbs/kft) Content % Size Rated (Ohms/kft) Ampacity* Code (AWG Stranding Breaking Individual Wire Comp. (amps) Word or (AL/STL) Strength DC @ AC @ kcmil) Steel Cable AL STL Total AL STL (lbs.) AL STL 20ºC 75ºC Core OD Turkey 6 6/1 0.0661 0.0661 0.0664 0.198 24.5 11.6 36 67.90 32.10 1,190 0.6410 0.806 105 Swan 4 6/1 0.0834 0.0834 0.0834 0.250 39.0 18.4 57 67.90 32.10 -

Avian Premaxilla and Tarsometatarsus from The

762 ShortCommunications andCommentaries [Auk,Vol. 112 The Auk 112(3):762-767, 1995 Avian Premaxilla and Tarsometatarsusfrom the Uppermost Cretaceous of Montana ANDRZEJ ELZANOWSKIa AND MICHAEL K. BRETT-$URMAN2 •Departmentof VertebrateZoology, National Museum of NaturalHistory, SmithsonianInstitution, Washington, D.C. 20560, USA; and 2Departmentof Geology,George Washington University, Washington, D.C. 20052,USA Despitea variety of fragmentary,apparently neog- is rounded and smooth,and the sidesare very steep. nathousavian fossilsknown from the uppermostCre- The largest among the neurovascularforamina scat- taceousdeposits (Brodkorb 1963, Olson 1985, Olson tered on each side are two elongatedorsal foramina: and Parris 1987),we still lack even an approximate the vessel from the rostral one coursed rostrad, whereas idea of how many neognathouslineages survived be- the vesselfrom the caudalone apparentlybifurcated yond the Cretaceous/Tertiaryboundary. Most of the into a smaller rostral and a larger caudal branch. In Maastrichtian avian bones reveal a charadriiform or addition, a number of smaller openingsperforates transitional charadriiform-gruiform morphology, eachside of the symphysis. which may be plesiomorphicfor most (Olson 1985) The ventral surfaceof the premaxillarysymphysis but probably not all of the neognaths(Elzanowski is strongly concave(Fig. lc, d). There are no distinct 1995). Other than that, there is some fossil evidence neurovascularforamina on the ventral (palatal) sur- for the existence of loons in the Cretaceous(Olson face,with the possibleexception of one small opening 1992)and mostly indirect evidencefor the pre-Ter- on the left side. The palatal shelvesof the premaxilla tiary origins of the relict pelecaniforms(Phaethon- begin from the symphysialtip and graduallybroaden tidae and Fregatidae) and procellariiforms (Elza- caudally where each of them occupiesone-third of nowski and Gaiton 1991). -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX A. VIRGINIA SPECIES OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Scientific Name Tier Cons. Opp. Habitat Descriptive Habitat Notes Name Ranking Amphibians Barking Hyla gratiosa II a Forest Forests near or within The Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information System indicates treefrog shallow wetlands the loss suitable wetlands constitute the greatest threats to this species. DGIF recommends working to maintain or restore forested buffers surrounding occupied wetlands. These needs are consistent with action plan priorities to conserve and restore wetland habitats and associated buffers. Recently discovered populations within its known range, may indicate this species is more abundant than previously believed. An in-depth investigation into its status may warrant delisting. This species will be prioritized as Tier 2a. Amphibians Blue Ridge Desmognathus IV c Forest High elevation seeps, This species' distribution is very limited. Other than limiting dusky orestes streams, wet rock faces, logging activity in the occupied areas, no conservation salamander and riparian forests actions have been identified. Unless other threats or actions are identified, this species will be listed as Tier 4c. Amphibians Blue Ridge Eurycea III a Wetland Mountain streams and The needs of this species are consistent with priorities for two-lined wilderae adjacent riparian areas maintaining and enhancing riparian forests and aquatic salamander with mixed hardwood or habitats. This species will be listed as Tier 3a. spruce-fir forests up to 6000 feet. Amphibians Carpenter Lithobates III a Wetland Freshwater wetlands with The needs of this species are consistent with action plan frog virgatipes sphagnum moss priorities to preserve and restore aquatic and wetland habitats and water quality. -

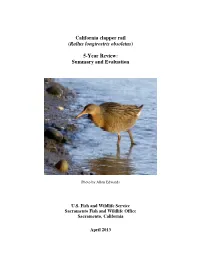

California Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris Obsoletus) 5-Year Review

California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus ) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photo by Allen Edwards U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office Sacramento, California April 2013 5-YEAR REVIEW California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. The California clapper rail was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act in 1970, so was not subject to the current listing processes and, therefore, did not include an analysis of threats to the California clapper rail. In this 5-year review, we will consider listing of this species as endangered or threatened based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of this species. We will consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

Guam Rail Conservation: a Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections

CONSERVATION & RESEARCH UPDATES FROM THE NATIONAL AVIARY SPRING 2021 Guam Rail Conservation: A Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections t the end of 2019 the conservation Working together through the Guam best of all, recent sightings of unbanded world celebrated a momentous Rail Species Survival Plan® (SSP), some rails there confirm that the species has achievement:A Guam Rail, once ‘Extinct twenty zoos strategized ways to ensure the already successfully reproduced in the in the Wild,’ was elevated to ‘Critically genetic diversity and health of this small wild for the first time in almost 40 years. Endangered’ status thanks to the recent population of Guam Rails in human care. The international collaboration that successful reintroduction of the species Their goal was to increase the size of the made the success of the Guam Rail to the wild. This conservation milestone zoo population and eventually introduce reintroduction possible likely will go is more than thirty years in the making— the species onto islands near Guam that down in conservation history. Behind the hoped-for result of intensive remained free of Brown Tree Snakes. every ko’ko’ once again living in the collaboration among multiple zoos and Guam wildlife officials have slowly wild is the very successful collaboration government agencies separated by oceans returned Guam Rails to the wild on the among many organizations and hundreds and continents. It is an extremely rare small neighboring islands of Cocos and of dedicated conservationists. conservation success story, shared by Rota. Reintroduction programs are most And we hope that there will be only one other bird: the iconic successful when local governments and California Condor. -

Pre-Lesson Plan

Pre-Lesson Plan Prior to taking part in the Winged Migration program at Tommy Thompson Park it is recommended that you complete the following lessons to familiarize your students with some of the birds they might see and some of the concepts they will learn during their field trip. The lessons can easily be integrated into your Science, Language Arts, Social Studies and Physical Education programs. Part 1: Amazing Birds As a class, read the provided “Wanted” posters. The posters depict a very small sampling of some of the amazing feats and features of birds. To complement these readings, display the following websites so that students can see some of these birds “up close.” Common Loon http://www.schollphoto.com/gallery/thumbnails.php?album=1 Black-Capped Chickadee http://sdakotabirds.com/species_photos/black_capped_chickadee.htm Ruby-Throated Hummingbird http://www.surfbirds.com/cgi-bin/gallery/search2.cgi?species=Ruby- throated%20Hummingbird Downy Woodpecker http://www.pbase.com/billko/downy_woodpecker Great Horned Owl www.owling.com/Great_Horned.htm When you visit Tommy Thompson Park, you may see chickadees, hummingbirds, and woodpeckers. These birds all breed in southern Ontario. However, you probably will not see a Great Horned Owl, because this specific bird is usually flying around at night. Below is a list of some other birds students might see when they visit Tommy Thompson Park. Have them chose one bird each and write a “Wanted” poster for it, focusing on a cool fact about that bird. Some web sites that will help them get started