Water Rail Stabbing Common Snipe Spur-Winged Lapwings Nesting On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecrex Restudied: a Small Eocene Guineafowl

TELECREX RESTUDIED: A SMALL EOCENE GUINEAFOWL STORRS L. OLSON In reviewing a number of the fossil species presently placed in the Rallidae, I have had occasion to examine the unique type-an incomplete femur-of Telecrex grangeri Wetmore (1934)) described from the Upper Eocene (Irdin Manha Formation) at Chimney Butte, Shara Murun region, Inner Mongolia. Although Wetmore assigned this fossil to the Rallidae, he felt that the species was distinct enough to be placed in a separate subfamily (Telecrecinae) ; this he considered to be ancestral to the modern Rallinae. After apparently ex- amining the type, Cracraft (1973b:17) assessed it as “decidedly raillike in the shape of the bone but distinct in the antero-posterior flattening of the head and shaft.” However, he suggested that Wetmores’ conclusions about its relationships to the Rallinae would have to be re-evaluated. Actually, Tele- crex bears very little resemblance to rails, and the distinctive proximal flat- tening of the shaft (but not of the head, contra Cracraft) is a feature peculiar to certain of the Galliformes. Further, my comparisons show Telecrex to be closest to the guineafowls (Numididae), a family hitherto known only from Africa and Europe. DISCUSSION The type specimen of Telecrex grangeri (AMNH 2942) is a right femur, lacking the distal end and part of the trochanter (Fig. 1). Its measurements are: proximal width 11.6 mm, depth of head 4.2, width of shaft at midpoint 4.6, depth of shaft at midpoint 4.1, overall length (as preserved ) 46.1. Telecrex differs from all rails -

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

South Africa Rallid Quest 15Th to 23Rd February 2019 (9 Days)

South Africa Rallid Quest 15th to 23rd February 2019 (9 days) Buff-spotted Flufftail by Adam Riley RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 2 Never before in birding history has a trip been offered as unique and exotic as this Rallid Quest through Southern Africa. This exhilarating birding adventure targets every possible rallid and flufftail in the Southern African region! Included in this spectacular list of Crakes, Rails, Quails and Flufftails are near-mythical species such as Striped Crake, White-winged, Streaky-breasted, Chestnut-headed and Striped Flufftails and Blue Quail, along with a supporting cast of Buff-spotted and Red-chested Flufftails, African, Baillon’s, Spotted and Corn Crakes, African Rail, Allen’s Gallinule, Lesser Moorhen and Black-rumped Buttonquail. As if these once-in-a-lifetime target rallids and rail-like species aren’t enough, we’ll also be on the lookout for a number of the region’s endemics and specialties, especially those species restricted to the miombo woodland, mushitu forest and dambos of Zimbabwe and Zambia such as Chaplin’s and Anchieta’s Barbet, Black-cheeked Lovebird, Bar-winged Weaver, Bocage’s Akalat, Ross’s Turaco and Locust Finch to mention just a few. THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE MAIN TOUR ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Johannesburg and drive to Dullstroom Day 2 Dullstroom area Day 3 Dullstroom to Pietermaritzburg via Wakkerstroom Day 4 Pietermaritzburg and surrounds Day 5 Pietermaritzburg to Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills Day 6 Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills Day 7 Ntsikeni, Drakensberg Foothills to Johannesburg Day 8 Johannesburg to Zaagkuilsdrift via Marievale and Zonderwater Day 9 Zaagkuilsdrift to Johannesburg and departure RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 3 TOUR ROUTE MAP… RBT Rallid Quest Itinerary 4 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Johannesburg and drive to Dullstroom. -

Houde2009chap64.Pdf

Cranes, rails, and allies (Gruiformes) Peter Houde of these features are subject to allometric scaling. Cranes Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Box 30001 are exceptional migrators. While most rails are generally MSC 3AF, Las Cruces, NM 88003-8001, USA ([email protected]) more sedentary, they are nevertheless good dispersers. Many have secondarily evolved P ightlessness aJ er col- onizing remote oceanic islands. Other members of the Abstract Grues are nonmigratory. 7 ey include the A nfoots and The cranes, rails, and allies (Order Gruiformes) form a mor- sungrebe (Heliornithidae), with three species in as many phologically eclectic group of bird families typifi ed by poor genera that are distributed pantropically and disjunctly. species diversity and disjunct distributions. Molecular data Finfoots are foot-propelled swimmers of rivers and lakes. indicate that Gruiformes is not a natural group, but that it 7 eir toes, like those of coots, are lobate rather than pal- includes a evolutionary clade of six “core gruiform” fam- mate. Adzebills (Aptornithidae) include two recently ilies (Suborder Grues) and a separate pair of closely related extinct species of P ightless, turkey-sized, rail-like birds families (Suborder Eurypygae). The basal split of Grues into from New Zealand. Other extant Grues resemble small rail-like and crane-like lineages (Ralloidea and Gruoidea, cranes or are morphologically intermediate between respectively) occurred sometime near the Mesozoic– cranes and rails, and are exclusively neotropical. 7 ey Cenozoic boundary (66 million years ago, Ma), possibly on include three species in one genus of forest-dwelling the southern continents. Interfamilial diversifi cation within trumpeters (Psophiidae) and the monotypic Limpkin each of the ralloids, gruoids, and Eurypygae occurred within (Aramidae) of both forested and open wetlands. -

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis Tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025

Conservation Strategy and Action Plan for the Great Bustard (Otis tarda) in Morocco 2016–2025 IUCN Bustard Specialist Group About IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN’s work focuses on valuing and conserving nature, ensuring effective and equitable governance of its use, and deploying nature- based solutions to global challenges in climate, food and development. IUCN supports scientific research, manages field projects all over the world, and brings governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO Members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org About the IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation The IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation was opened in October 2001 with the core support of the Spanish Ministry of Environment, the regional Government of Junta de Andalucía and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID). The mission of IUCN-Med is to influence, encourage and assist Mediterranean societies to conserve and sustainably use natural resources in the region, working with IUCN members and cooperating with all those sharing the same objectives of IUCN. www.iucn.org/mediterranean About the IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of 9,000 experts. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

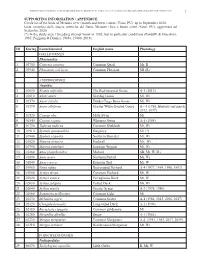

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced

ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced APPLICATION: STANDARDS: ACSR – Aluminum Conductor Steel Reinforced is used as bare • B-230 Aluminum wire, 1350-H19 for Electrical Purposes overhead transmission cable and as primary and secondary • B-232 Aluminum Conductors, Concentric-Lay-Stranded, distribution cable. ACSR offers optimal strength for line design. Coated Steel Reinforced (ACSR) BARE ALUMINUM Variable steel core stranding for desired strength to be achieved • B-341 Aluminum-Coated Steel Core Wire for Aluminum without sacrificing ampacity. Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR/AZ) • B-498 Zinc-Coated Steel Core Wire for Aluminum CONDUCTORS: Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR) • B-500 Metallic Coated Stranded Steel Core for Aluminum • Aluminum alloy 1350-H119 wires, concentrically stranded Conductors, Steel Reinforced (ACSR) around a steel core available with Class A, B or C galvanizing; • RUS Accepted aluminum coated (AZ); or aluminum-clad steel core (AL). Additional corrosion protection is available through the application of grease to the core or infusion of the complete cable with grease. Also available with Non Specular surface finish. Resistance** Diameter(inch) Weight (lbs/kft) Content % Size Rated (Ohms/kft) Ampacity* Code (AWG Stranding Breaking Individual Wire Comp. (amps) Word or (AL/STL) Strength DC @ AC @ kcmil) Steel Cable AL STL Total AL STL (lbs.) AL STL 20ºC 75ºC Core OD Turkey 6 6/1 0.0661 0.0661 0.0664 0.198 24.5 11.6 36 67.90 32.10 1,190 0.6410 0.806 105 Swan 4 6/1 0.0834 0.0834 0.0834 0.250 39.0 18.4 57 67.90 32.10 -

Environmental Impact Report

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT SUPPLEMENT TO THE REPORT ON THE ENVIROMENTAL IMPACT OF THE “CONSTRUCTION OF THE KARCINO-SARBIA WIND FARM (17 WIND TURBINES)” OF 2003 Name of the undertaking: KARCINO-SARBIA Wind Farm (under construction) Contractor: AOS Agencja Ochrony Środowiska Sp. z o.o. based in Koszalin Arch. No. 52/OŚ/OOS/06 Koszalin, September 2006 Team: Bogdan Gutkowski, M.Sc.Eng.– Expert for Environmental Impact Assessment Appointed by the Governor of the West Pomerania Province Marek Ziółkowski, M.Sc. Eng. – Environmental Protection Expert of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Natural Resources and Forestry; Environmental Protection Consultant Dagmara Czajkowska, M.Sc. Eng. – Specialist for Environmental Impact Assessment, Specialist for Environmental Protection and Management Ewa Reszka, M.Sc. – Specialist for the Protection of Water and Land and Protection against Impact of Waste Damian Kołek, M.Sc.Eng. – Environmental Protection Specialist 2 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 II. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE PROJECT ..................................................... 9 1. Location and adjacent facilities....................................................................................................... 9 2. Modifications to the project .......................................................................................................... 10 3. Technical description of the project .............................................................................................. -

GRUIFORMES Rallus Aquaticus Water Rail Rascón Europeo

http://blascozumeta.com Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze GRUIFORMES 3 2 Rallus aquaticus Water Rail 4 Rascón europeo 5 1 MOULT Complete postbreeding moult, usually finished in Sep- tember. Partial postjuvenile moult involving body feathers and, sometimes, tail feathers; often finished in Ageing. Spring. Adult. Head and October. Both age classes have a prebreeding moult breast pattern: reduced whitish confined to body feathers. chin and throat all grey (1); without a pale streak above the MUDA eye (2); iris (3) and bill (4) red- Muda postnupcial completa, habitualmente terminada dish; breast with all feathers uni- en septiembre. Muda postjuvenil parcial cambiando form slate grey (5). plumas corporales y, a veces, plumas de la cola; gene- Edad. Primavera. Adulto. Diseño de cabeza y pecho: ralmente terminada en octubre. Ambos tipos de edad mentón con mancha blanca reducida y garganta gris tienen una muda prenupcial que incluye solo plumas uniforme (1); sin una línea clara sobre el ojo (2); corporales. iris (3) y pico (4) rojizos; pecho con todas las plu- mas de color gris-ceniza uniforme (5). SEXING Plumage of both sexes alike. Size can be an useful characteristic with most of the specimens: male with 3 2 wing longer than 120 mm, tarsus longer than 40 mm. 4 Female with wing shorter than 115 mm, tarsus shorter than 37 mm. SEXO 5 Ambos sexos con plumaje similar. El tamaño puede separar la mayor parte de los ejemplares: macho con ala mayor de 120 mm, tarso mayor de 40 mm; hembra con ala menor de 115 mm, tarso menor de 37 mm. -

INDEX to VOLUME 71 Compiled by L

109}ti] 499 INDEX TO VOLUME 71 Compiled by L. R. Wolfe Acanthis taminca, 353 Amazilia amabilis costaricensis, 468 Accentor, Alpine, 64, 70 amabilis decora, 468 Accipiter, 353 edward edward, 468 cooperil, 195 edward niveoventer, 467, 468 nisus, 262 tzacafi tzacafi, 467, 468 Aceros, leucocephalus, 474 Ammann, George A., unpub. thesis, the plicatus, 474 life history and distribution of the Acrocephalus familiaris, 188 Yellow-headed Blackbird, 191 scirpaceus, 262 Ammospiza caudacuta, 65 Aechmophorus occidentalis, 333 Anas acura, 310, 461 Aegolius, 173 acura tzitzihoa, 310 A•ronautes saxatalis, 466 laysanensis, 188 Aethopyga ignicauda, 172 platyrhynchos, 197, 267-270 Africa, 12, 13, 89 rubripes, 192 Agelaius icterocephalus, 152 Anatidae, 90, 460, 474 phoeniceus, 46, 65, 137-155, 279, Anatinae, 196 461 Anthracothorax, 467, 468 phoeniceus utahensis, 140 nigricollis nigricollis, 468 ruficapillus, 152 Antigua, 329 tricolor, 151 Antipodes Island, 249, 251 Aix sponsa, 267, 459, 461 A.O.U., Check-list Committee, twenty- Alaska, 203, 209, 351-365 ninth supplement to the Ameri- Albatross, 188, 239-252 can Oruithologists' Union check- Laysan, 211 list of North American birds, 310- Light-mantled Sooty, 239, 249, 251 312 Royal, 239-252 check-list ranges, 156-163 Wandering, 240, 241, 243, 244, 248, committees, 85 249, 251 Committee on the Nomination of Albinism, 137-155, pl. 11 Associates, 233 Alca torda, 463 officers,trustees, and committees, 85 Aleidac, 192 report of the Advisory Committee Allen, Robert P., additional data on the on Bird Protection, 186-190 food of the Whooping Crane, 198 report of Research Committee on Allison, Donald G., unpub. thesis, bird unpublishedtheses in ornithology, populations of forest and forest edge 191-197 in central Illinois, 191 resolutions, 84 Allison, John E., unpub. -

Wild Birds and Avian Influenza

5 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual WILD BIRDS AND AVIAN INFLUENZA An introduction to applied field research and disease sampling techniques Cover photographs: Left image: USGS Western Ecological Research Center Centre and right images: Rob Robinson manual5.indb Sec1:ii 19/03/2008 10:15:44 5 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual WILD BIRDS AND AVIAN INFLUENZA An introduction to applied field research and disease sampling techniques Darrell Whitworth, Scott Newman, Taej Mundkur, Phil Harris FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2007 manual5.indb Sec2:i 19/03/2008 10:16:56 Authors’ details Darrell Whitworth Wildlife Consultant Via delle Vignacce 12 - Staggiano 52100, Arezzo, Italy [email protected] Scott Newman Animal Health Service, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy [email protected] Taej Mundkur Animal Health Service, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy [email protected] Phil Harris Animal Health Service, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy [email protected] Recommended citation FAO. 2007. Wild Birds and Avian Influenza: an introduction to applied field research and disease sampling techniques. Edited by D. Whitworth, S.H. Newman, T. Mundkur and P. Harris. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual, No. 5. Rome. (also available at www.fao.org/avianflu) The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.