Diefenbaker's Legacy: New Ways of Thinking About Nuclear Weapons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (PDF)

N° 3/2019 recherches & documents March 2019 Disarmament diplomacy Motivations and objectives of the main actors in nuclear disarmament EMMANUELLE MAITRE, research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-490100-19-4 EAN : 9782490100194 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1 – A CONVERGENCE OF PACIFIST AND HUMANITARIAN TRADITIONS ....................................... 8 1.1 – Neutrality, non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament .......................... 8 1.1.1 – Disarmament in the neutralist tradition .............................................................. 8 1.1.2 – Nuclear disarmament in a pacifist perspective .................................................. 9 1.1.1 – "Good international citizen" ..............................................................................11 1.2 – An emphasis on humanitarian issues ...............................................................13 1.2.1 – An example of policy in favor of humanitarian law ............................................13 1.2.2 – Moral, ethics and religion .................................................................................14 -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

R=Nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- R.104TA (-{, 001

3Kcnen~lHrn 3 . ~ ,_ CCCP r=nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- r.104TA (-{, 001 diasporiana.org.ua CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON CANADIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS Unive~ty Partnership Centre I Georgian College, Barrie, ON Vol. 9 I Canada/Russia Series J.L. Black ef Andrew Donskov, general editors CRCR One-Way Ticket The Soviet Return-to-the-Homeland Campaign, 1955-1960 Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko Penumbra Press I Manotick, ON I 2008 ,l(apyHoK OmmascbKozo siooiny KaHaOCbKozo Tosapucmsa npuHmeniB YKpai°HU Copyright © 2008 Library and Archives Canada SERGE CIPKO & GLENNA ROBERTS Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No part of this publication may be Roberts, Glenna, 1934- reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Cipko, Serge, 1961- or transmitted, in any1'0rm or by any means, without the prior written One-way ticket: the Soviet return-to consent of the publisher or a licence the-homeland campaign, 1955-1960 I from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko. Agency (Access Copyright). (Canada/Russia series ; no. 9) PENUMBRA PRESS, publishers Co-published by Centre for Research Box 940 I Manotick, ON I Canada on Canadian-Russian Relations, K4M lAB I penumbrapress.ca Carleton University. Printed and bound by Custom Printers, Includes bibliographical references Renfrew, ON, Canada. and index. PENUMBRA PRESS gratefully acknowledges ISBN 978-1-897323-12-0 the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing L Canadians-Soviet Union Industry Development Program (BPIDP) History-2oth century. for our publishing activities. We also 2. Repatriation-Soviet Union acknowledge the Government of Ontario History-2oth century. through the Ontario Media Development 3. Canadians-Soviet Union Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative. -

The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century

“No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century by Kevin Woodger A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Kevin Woodger 2020 “No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century Kevin Woodger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation examines the Canadian Cadet Movement and Boy Scouts Association of Canada, seeking to put Canada’s two largest uniformed youth movements for boys into sustained conversation. It does this in order to analyse the ways in which both movements sought to form masculine national and imperial subjects from their adolescent members. Between the end of the First World War and the late 1960s, the Cadets and Scouts shared a number of ideals that formed the basis of their similar, yet distinct, youth training programs. These ideals included loyalty and service, including military service, to the nation and Empire. The men that scouts and cadets were to grow up to become, as far as their adult leaders envisioned, would be disciplined and law-abiding citizens and workers, who would willingly and happily accept their place in Canadian society. However, these adult-led movements were not always successful in their shared mission of turning boys into their ideal-type of men. The active participation and complicity of their teenaged members, as peer leaders, disciplinary subjects, and as recipients of youth training, was central to their success. -

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020 Luc-André Brunet. “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983–1984.” The International History Review 41:6 (2019): 1145-1167. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1472623. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR957 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Commissioning Editor: Cindy Ewing | Production Editor: George Fujii Review by Greg Donaghy, University of Toronto here are very few episodes in Canada’s diplomatic history—and none so unsuccessful—that that have attracted the scholarly ink reserved for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s controversial peace initiative at the height of the second T Cold War in the fall of 1983.1 The latest entry is Luc-André Brunet’s award-winning article, “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983-1984.” Superbly researched in seven national archives, carefully argued, and presented with verve and spirit, “Unhelpful Fixer” will quite probably remain the last word on the subject for some time to come. For Brunet, the story starts in the summer of 1983, when Trudeau, already fifteen years in power, cast about for a dramatic foreign policy initiative that would restore his cratering poll numbers. Horrified by Moscow’s decision to shoot-down an errant Korean airliner over Soviet airspace on 1 September 1983, Trudeau leapt into action. Sidelining the foreign and defence policy establishment, he assembled a Task Force of mid-level officials, and asked it to cobble together a series of arms control and disarmament measures to “change the trend line” (1148) in East-West relations and reduce the brittle tensions between the United States and the USSR. -

A Tribute to the Honourable R. Gordon Robertson, P.C., C.C., LL.D., F.R.S.C., D.C.L

A Tribute to The Honourable R. Gordon Robertson, P.C., C.C., LL.D., F.R.S.C., D.C.L. By Thomas d’Aquino MacKay United Church Ottawa January 21, 2013 Reverend Doctor Montgomery; members of the Robertson family; Joan - Gordon’s dear companion; Your Excellency; Madam Chief Justice; friends, I am honoured – and humbled – to stand before you today, at Gordon’s request, to pay tribute to him and to celebrate with you his remarkable life. He wished this occasion to be one, not of sadness, but of celebration of a long life, well lived, a life marked by devotion to family and to country. Gordon Robertson – a good, fair, principled, and ever so courteous man - was a modest person. But we here today know that he was a giant. Indeed, he has been described as his generation’s most distinguished public servant – and what a generation that was! Gordon was proud of his Saskatchewan roots. Born in 1917 in Davidson – a town of 300 “on the baldest prairie”, in Gordon’s words, he thrived under the affection of his Norwegian-American mother and grandparents. He met his father – of Scottish ancestry - for the first time at the age of two, when he returned home after convalescing from serious wounds suffered at the epic Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge. He was, by Gordon’s account, a stern disciplinarian who demanded much of his son in his studies, in pursuit of manly sports, and in his comportment. Gordon did not disappoint. He worked his way through drought- and depression-torn Saskatchewan, attended Regina College and the University of Saskatchewan, and in 1938 was on his way to Oxford University, a fresh young Rhodes Scholar. -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

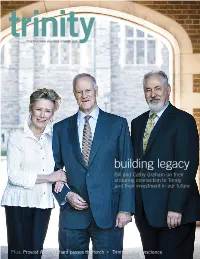

Building Legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on Their Enduring Connection to Trinity and Their Investment in Our Future

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch • Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply flies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or five years of living and learning and growing and gaining fined the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long after the place itself has been left behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire office. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Office friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Affairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long after Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

L'absence De Généraux Canadiens-Français Combattants

Où sont nos chefs? L’absence de généraux canadiens-français combattants durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (1939-1945). Par : Alexandre Sawyer Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales À titre d’exigence partielle en vue de l’obtention d’un doctorat en histoire Université d’Ottawa © Alexandre Sawyer, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 ii RÉSUMÉ Le nombre d’officiers généraux canadiens-français qui ont commandé une brigade ou une division dans l’armée active durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale est presque nul. On ne compte aucun commandant de division francophone dans l’armée outre-mer. Dans les trois premières années de la guerre, seulement deux brigadiers canadiens-français prennent le commandement de brigades à l’entrainement en Grande-Bretagne, mais sont rapidement renvoyés chez eux. Entre 1943 et 1944, le nombre de commandants de brigade francophones passe de zéro à trois. L’absence de généraux canadiens-français combattants (à partir du grade de major-général) durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale s’explique par plusieurs facteurs : le modèle britannique et l’unilinguisme anglais de la milice, puis de l’armée canadienne, mais aussi la tradition anti-impérialiste et, donc, souvent antimilitaire des Canadiens français. Au début de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, aucun officier canadien n’est réellement capable de commander une grande unité militaire. Mais, a-t-on vraiment le choix? Ces officiers sont les seuls dont dispose le Canada. Quand les troupes canadiennes sont engagées au combat au milieu de 1943, des officiers canadiens, plus jeunes et beaucoup mieux formés prennent la relève. À plus petite échelle, le même processus s’opère du côté francophone, mais plus maladroitement. -

LAST POST November 2019 LAST POST Legion Magazine Publishes the Last Post Annually As Long As the Date of Death Is Within the Time During the Remembrance Day Period

LAST POST November 2019 LAST POST Legion Magazine publishes the Last Post annually As long as the date of death is within the time during the Remembrance Day period. This free period of entries on the website (1984 to present), service recognizes those who have served their the notice will be added to the database and country and allows our readers to learn of the appear in the printed edition. Notices within a passing of comrades with whom they served. year of the date of death can be submitted by Last Post is reserved for these groups: family members, but entries before that time 1) ordinary members of The Royal Canadian period must come from a Royal Canadian Legion at the time of death; 2) RCL life members Legion branch. who were previously ordinary members; and These entries are added to the searchable 3) Canadian war veterans (WW II, Korean War, Last Post database at www.legionmagazine.com. Gulf War, Afghanistan) who were not Legion members at the time of death. Legion Magazine relies on RCL branches to Copyright provide the Last Post information. Please use the Reproduction or re-creation of the Last Post Section, current Last Post form, dated January 2016, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly which is available from the Dominion forbidden and is a violation of copyright, which Command Supply Department. resides with Legion Magazine and its publisher, Branches should submit notices to Legion Canvet Publications Ltd. Magazine promptly to ensure timely publication. AITKEN, Neil—May 4, 2019, age 81. -

OLIGARCHS at OTTAWA, PART II Night a Success

/ Oligarchs at Otta-wa ..: Austin F. Cross ' ' VERY year on budget night, like an to advise the minister (that's the term, E unspectacular star at the tail of but actually our man writes the stuff) on that bright comet, the Hon. Douglas the technical aspects of taxation. His Abbott, there moves into the Press Gal- is the ethical concept of taxation. Not lery ' reception rQom, among others, Ken' immediately has he to be concerned with Eaton. In title, Assistant Deputy Minister such matters as whether the Fisheries of Finance: in fact, he is the fell ow who needs the money, or Trade and Com- wrote a lot of <the budget that the Hon. merce is bungling its administration. Ra- Mr. Abbott has just so entertainingly given. ther would it be his role to assess nicely, There are other tail-stars, of course, to the what for example, would be the effect of Abbott comet. Yet paradoxically none one cent more tax on cigarettes, or the will seem duller, none will be brighter, precise incidence of sales tax. than the same Ken Eaton. For a fellow _He and Harry Perry are a very good who has just heard a lot of his own fiscal team, and when they sit down to write theory and financial policy given to the their share of the budget, you have people of Canada in particular and the a brilliant duet being played. world in general, Ken Eaton is quiet "He's without a peer in his field," said enough. an expert enthusiastically, in discussing There he sits, a man who would pass in Eaton, and this expert is one man rarely a crowd. -

Book Reviews

333 Book Reviews E. Shragge, R. Babin, and J.G. Vaillancourt, (Editors). ROOTS OF PEACE: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST MIUTARISM IN CANADA. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1986. 203 pp. $12.95 Roots of Peace: The Movemenl Against Militarism in Canada is a collection of articles on a wide range of peace-re1ated issues, from Canada's role in NATO to liberation struggles in the Third World. The book's contributors include disannament activists, feminists, community organizers, academics, and a retired general. However, despite this diversity of issues and perspectives, the book's 13 articles leave one with a single, two-part message. The flCSt part: Canada is a full and voluntary player in the anns race. We are told to look beyond Washington and Moscow to find reasons for increased global militarization. We should look closer to home, at our communities, our places of work. We should look to Canada's economic system, its profit from anns sales, its tteatment of women and developing nations, its relationship with the U.S. The second part of the book's message is that Canadians cao do something to halt the anns race. The reader is advised, however, to put little hope in politicians or superpower summits. Again, we should look closer to home, at ourselves, our involvenient in efforts for peace. The book has two sections: "An International Perspective on the Peace Movement" and "Organizing for Peace." The first section places Canadian involvement in the anns race into a global context and deals with sorne of the larger issues: Canada's role in NATO and its relationship to the U.S., disarmament movements in Europe, the Third World and supeIpOwer politics, the need for a non-aligned peace movement, and that perennial question, "What about the Russians?" 334 Book Reviews The second section describes specific examples of what the Editors calI "detente from below"; that is, a grassroots movement of ordinary people committed to breaking the cycles of power and paranoïa which keep all of us locked in the arms race.