"The Emergence (Or Not) of Private Property Rights in Land: Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

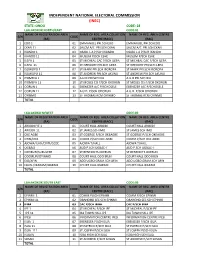

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

1 CHAPTER ONE GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 Background To

CHAPTER ONE GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 Background to the Study Acts of conflict and violence occur daily in different parts of the world. This is due to a variety of motives, which include political fanaticism, ethnic hatred, religious extremism and ideological differences. Conflict is perennial and an ingredient towards the actualization of individual and group interests. According to S.A. Ayinla, it is a natural announcement of an impending re-classification of a society with changed characteristics and goals and with new circumstances of survival and continuity1. Conflict is a universal human experience. Its origin and nature are best explained within the framework of human nature and environment in which man lives2.Conflicts and violence are common factors in both secular and sacred institutions. In spite of the fact that the church is believed to be a holy institution ordained by God, she has never at any time outgrown conflicts and violence. This is due to the fact that, the affairs of the church are administered by human beings who are not always perfect or faultless. By 1975, the Warri Diocese, Anglican Communion, had not existed as a corporate Christian entity. The year _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 1S.A Ayinla (ed.) Issues in Political Violence in Nigeria, llorin: Hamson Printers, 2005, p.19. 2O.I. Albert, Tinu Awe et al (eds) Informal Channels for Conflict Resolution in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ibadan Inter Printer 1992 p.2 1 witnessed real grassroots mobilization for its creation3. But by the year 2000, the Diocese had existed for over twenty years and had given birth to two other Dioceses, viz; Ughelli and Oleh (Isoko) Dioceses. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 71 (2015) Article 5 Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Borrows, John. "Aboriginal Title and Private Property." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 71. (2015). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol71/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows* Q: What did Indigenous Peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? A: “OURS.”1 I. INTRODUCTION In the ground-breaking case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia2 the Supreme Court of Canada recognized and affirmed Aboriginal title under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.3 It held that the Tsilhqot’in Nation possess constitutionally protected rights to certain lands in central British Columbia.4 In drawing this conclusion the Tsilhqot’in secured a declaration of “ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land”.5 These are wide-ranging rights. -

For Multi-Ethnic Harmony in Nigeria

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1974 Curriculum (English language) for multi-ethnic harmony in Nigeria. M. Olu Odusina University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Odusina, M. Olu, "Curriculum (English language) for multi-ethnic harmony in Nigeria." (1974). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2884. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2884 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S/AMHERST 315DbbD13Sfl3DflO CURRICULUM (ENGLISH LANGUAGE) FOR MULTI-ETHNIC HARMONY IN NIGERIA A Dissertation Presented By Margaret Olufunmilayo Odusina Submitted to the graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial degree fulfillment of the requirements for the DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August, 1974 Major Subject: Education ii (C) Margaret Olufunmilayo Odusina 1974 All Rights Reserved iii ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM FOR MULTI-ETHNIC HARMONY IN NIGERIA A Dissertation By Margaret 0. Odusina Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Norma J/an Anderson, Chairman of Committee a iv DEDICATION to My Father: Isaac Adekoya Otunubi Omo Olisa Abata Emi Odo ti m’Odosan Omo• « • * Ola baba ni m’omo yan » • • ' My Mother: Julianah Adepitan Otunubi Omo Oba Ijasi 900 m Ijasi elelemele alagada-m agada Ijasi ni Oluweri ke soggdo My Children: Omobplaji Olufunmilayo T. Odu§ina Odusina Omobolanle Oluf unmike K. • • » • Olufunmilola I. Odusina Omobolape * • A. -

Here Is a List of Assets Forfeited by Cecilia Ibru

HERE IS A LIST OF ASSETS FORFEITED BY CECILIA IBRU 1. Good Shepherd House, IPM Avenue , Opp Secretariat, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers) 2. Residential block with 19 apartments on 34, Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Dilivent International Limited). 3.20 Oyinkan Abayomi Street, Victoria Island (remainder of lease or tenancy upto 2017). 4. 57 Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi. 5. 5A George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited), 6. 5B George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 7. 4A Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 8. 4B Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 9. 16 Glover Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 10. 35 Cooper Road , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 11. Property situated at 3 Okotie-Eboh, SW Ikoyi. 12. 35B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi. 13. 38A Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Meeky Enterprises Limited). 14. 38B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Aleksander Stankov). 15. Multiple storey multiple user block of flats under construction 1st Avenue , Banana Island , Ikoyi, Lagos , (with beneficial interest therein purchased from the developer Ibalex). 16. 226, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 17. 182, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos , (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 18. 12-storey Tower on one hectare of land at Ozumba Mbadiwe Water Front, Victoria Island . -

LAND TITLES the Following Is General Information About Land Titles

LAND TITLES The following is general information about land titles. It does not replace a lawyer’s advice about a specific legal problem. Everyone’s situation is different, so you may need to get legal help about your matter. Is all the land in the province owned by someone Courts will enforce those rights and make sure that others, or is some of the land public land? including governments, respect them. The Province owns about 35% of the land in Nova Scotia, and the rest of the land (about 65%) is owned privately, or by the federal Where a person does not have title to a specific piece of land, and municipal governments. The majority of the publicly owned they may be denied the opportunity to exercise these rights. land is managed by the Department of Natural Resources. This land is often referred to as Crown lands. Having title to land means that the landowner must comply with the legal obligations of land ownership. These obligations will Can people buy Crown lands or other provincial vary depending on where that land is located. In Nova Scotia, the lands? main legal responsibilities of landowners include paying municipal The Province has been working to buy more land, and does not property taxes and following land use bylaws. If you don’t pay taxes sell a great deal of the land it owns because the percentage and follow applicable laws, the consequences can be severe – you of public land ownership in Nova Scotia is small compared to may need to pay a fine or you could lose title to your land. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

Download Download

Ib.J.Soc. Dec. 2014. Vol. 1 www.ibadanjournalofsociology.org Ibadan Journal of Sociology www.ibadanjournalofsociology.org The Biennial Journal of the Department of Sociology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. www.ibadansociology.org Ibadan Journal of Sociology is an open access, peer-reviewed journal that considers articles from sociology, anthropology and other related disciplines. The journal has a special focus on all aspects of social relations and the impact of social policies, practices and interventions on human relations. Ibadan Journal of Sociology focuses on the needs of individuals for reporting research findings, case studies and reviews. We offer an efficient, fair and friendly peer review service and are committed to publishing all sound scientific studies, especially where they advance knowledge in any human endeavour. Editor-in-Chief: Olutayo Akinpelu Olanrewaju Professor & Dean of Faculty of the Social Sciences Department of Sociology, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria. E-Mail: [email protected] Tel.: +234-8034006297 Members Okunola Rashid Akanji, Department Ogundiran Akin, Professor & Chair of Sociology, Faculty of the Social Africana Studies University of North Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Carolina, Charlotte, USA. Nigeria. Office: Garinger 113 A Email: [email protected] Phone: 704-687-2355 Email: [email protected] Akanle Olayinka, Department of Sociology, Faculty of the Social Adesina Jimi O, Professor of Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Sociology Nigeria Department of Anthropology and Email: [email protected] Sociology, University of Western Cape Bellville 7535, South Africa. Toreh Steve, Professor of Sociology, Email: [email protected] Department of Sociology, University of Ghana Frost Diane, Senior Lecturer, Email:[email protected] Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology, University of Mogalakwe, M, Professor of Liverpool, Eleanor Rathbone Sociology, Building, Bedford Street SouthL69 Department of Sociology, University of 7ZA, United Kingdom. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Afro-Descendants, Discrimination and Economic Exclusion in Latin America by Margarita Sanchez and Maurice Bryan, with MRG Partners

macro study Afro-descendants, Discrimination and Economic Exclusion in Latin America By Margarita Sanchez and Maurice Bryan, with MRG partners Executive summary Also, Afro-descendants do not have a significant voice in the This macro study addresses the economic exclusion of people planning, design or implementation of the policies and activi- of African descent (Afro-descendants) in Latin America. It ties that directly affect their lives and regions. This is an aims to examine how and why race and ethnicity contribute to important omission; while Afro-descendant populations may the disproportionately high levels of poverty and economic dis- be materially poor, they have a rich cultural heritage and access crimination in most Afro-descendant communities, and how to key natural resources. Development strategies need to recog- to promote change. nize the historical, social and cultural complexity of There are clear links between Afro-descendant communi- Afro-descendants’ poverty and consult them on the most cul- ties and poverty, however there is a need for disaggregated data turally appropriate means of achieving positive change. to provide a more precise picture, and to enable better plan- The views of Afro-descendants are central to much of the ning and financing of development programmes for this highly information used in this study, which uses a rights-based marginalized group. approach. The study explains some of the causes and conse- A prime cause for the lack of quantitative material, is that quences of Afro-descendants’ exclusion, and offers donors and governments have only recently begun to acknowl- recommendations for a more inclusive minority rights-based edge Afro-descendant populations’ existence.