Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Technical Committee Om

REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE January 2000 Contents: Volume I: Main Report Chapter One: Preliminary Matters Preamble Terms of Reference Modus Operandi Chapter Two: Consideration of Various Sections of the Constitution in Relation to Application of Sharia A. Section 4(6) B. Section 5(2) C. Section 6(2) D. Section 10 E. Section 38 F. Section 275(1) G. Section 277 Chapter Three: Observations and Recommendations 1. General Observations 2. Specific Recommendations 3. General Recommendations Conclusion Appendix A: List of all the Groups, Associations, Institutions and Individuals Contacted by the Committee Volume II: Verbatim Proceedings Zone 1: Funtua: Funtua, Bakori, Danja, Faskari, Dandume and Sabuwa Zone 2: Malumfashi: Malumfashi, Kafur, Kankara and Musawa Zone 3: Dutsin-Ma: Dutsin-Ma, Danmusa, Batsari, Kurfi and Safana Zone 4: Kankia: Kankia, Ingawa, Kusada and Matazu Zone 5: Daura: Daura, Baure, Zango, Mai’adua and Sandamu Zone 6: Mani: Mani, Mashi, Dutsi and Bindawa Zone 7: Katsina: Katsina, Kaita, Rimi, Jibia, Charanchi and Batagarawa 1 Ostien: Sharia Implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A Sourcebook: Supplement to Chapter 2 REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT CHAPTER ONE Preamble The Committee was inaugurated on the 20th October, 1999 by His Excellency, the Governor of Katsina State, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’adua, at the Council Chambers, Government House. In his inaugural address, the Governor gave four point terms of reference to the Committee. He urged members of the Committee to work towards realising the objectives for which the Committee was set up. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Federalism and Political Problems in Nigeria Thes Is

/V4/0 FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA THES IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Olayiwola Abegunrin, B. S, Denton, Texas August, 1975 Abegunrin, Olayiwola, Federalism and PoliticalProblems in Nigeria. Master of Arts (Political Science), August, 1975, 147 pp., 4 tables, 5 figures, bibliography, 75 titles. The purpose of this thesis is to examine and re-evaluate the questions involved in federalism and political problems in Nigeria. The strategy adopted in this study is historical, The study examines past, recent, and current literature on federalism and political problems in Nigeria. Basically, the first two chapters outline the historical background and basis of Nigerian federalism and political problems. Chapters three and four consider the evolution of federal- ism, political problems, prospects of federalism, self-govern- ment, and attainment of complete independence on October 1, 1960. Chapters five and six deal with the activities of many groups, crises, military coups, and civil war. The conclusions and recommendations candidly argue that a decentralized federal system remains the safest way for keeping Nigeria together stably. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES0.0.0........................iv LIST OF FIGURES . ..... 8.............v Chapter I. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .1....... Geography History The People Background to Modern Government II. THE BASIS OF NIGERIAN POLITICS......32 The Nature of Politics Cultural Factors The Emergence of Political Parties Organization of Political Parties III. THE RISE OF FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA. ....... 50 Towards a Federation Constitutional Developments The North Against the South IV. -

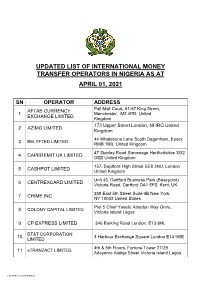

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

House of Reps Order Paper Thursday 15 July, 2021

121 FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019–2023) THIRD SESSION NO. 14 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Thursday 15 July 2021 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Messages from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Messages from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matters of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal College of Education (Technical) Aghoro, Bayelsa State (Establishment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1429) (Hon. Agbedi Yeitiemone Frederick) - First Reading. 2. National Eye Care Centre, Kaduna (Establishment, Etc) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1439) (Hon. Pascal Chigozie Obi) - First Reading. 3. Electronic Government (e-Government) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1432) (Hon. Sani Umar Bala) - First Reading. 4. Federal Medical Centre Zuru (Establishment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1443) (Hon. Kabir Ibrahim Tukura) - First Reading. 5. National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021(HB. 1445) (Hon. Sergius Ogun) - First Reading. 122 Thursday 15 July 2021 No. 14 6. Industrial Training Fund Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1447) (Hon. Patrick Nathan Ifon) - First Reading. 7. Fiscal Responsibility Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1534) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 8. Federal Highways Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1535) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 9. Border Communities Development Agency (Establishment) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1536) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 10. Borstal Institutions and Remand Centres Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. -

Integrating Renewable Energy Into Nigeria's Energy

Master’s Thesis 2017 30 ECTS Faculty of Landscape and Society Department of International Environment and Development Studies Integrating Renewable Energy into Nigeria’s Energy Mix: Implications for Nigeria’s Energy Security Obideyi Oluwatoni International Development Studies The Department of International Environmental and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments The Noragric Master theses are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master programme “International Environmental Studies”, “International Development Studies” and “International relations”. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on the condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric © Oluwatoni Onyeka obideyi, August 2017 [email protected] Noragric Department of Internationl Environmental and Development Studies Faculty of Lnadscape and Scoiety P.O. Box 5003 N- 1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 67 23 00 00 Internet: https://www.nmbu.no/fakultet/landsam/institutt/noragric i DECLARATION I, Oluwatoni Onyeka Obideyi, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Signature……………………………… Date……………………………………. ii Dedicated to my mother- Florence Ngozi Bolarinwa of blessed memory. -

From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940

The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History ISSN: 0308-6534 (Print) 1743-9329 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fich20 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly To cite this article: Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2019) From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 47:3, 474-489, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 Published online: 15 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fich20 THE JOURNAL OF IMPERIAL AND COMMONWEALTH HISTORY 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 474–489 https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Indirect rule figured prominently in Nigeria’s colonial Nigeria; Abeokuta; crime; administration, but historians understand more about the police; indirect rule abstract tenets of this administrative strategy than they do about its everyday implementation. This article investigates the early history of the Native Authority Police Force in the town of Abeokuta in order to trace a larger move towards coercive forms of administration in the early twentieth century. In this period the police in Abeokuta developed from a primarily civil force tasked with managing crime in the rapidly growing town, into a political implement of the colonial government. -

Freedom As Marronage

Freedom as Marronage Freedom as Marronage NEIL ROBERTS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Neil Roberts is associate professor of Africana studies and a faculty affiliate in political science at Williams College. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2015 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2015. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (paper) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226201184.001.0001 Jacket illustration: LeRoy Clarke, A Prophetic Flaming Forest, oil on canvas, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Roberts, Neil, 1976– author. Freedom as marronage / Neil Roberts. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (pbk : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) 1. Maroons. 2. Fugitive slaves—Caribbean Area. 3. Liberty. I. Title. F2191.B55R62 2015 323.1196'0729—dc23 2014020609 o This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48– 1992 (Permanence of Paper). For Karima and Kofi Time would pass, old empires would fall and new ones take their place, the relations of countries and the relations of classes had to change, before I discovered that it is not quality of goods and utility which matter, but movement; not where you are or what you have, but where you have come from, where you are going and the rate at which you are getting there. -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

Government and Political Institution Course

NAME: GARBA ZAINAB BAKO MATRIC NUMBER: 19/MHS11/065 DEPARTMENT: PHARMACY COURSE: GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL INSTITUTION COURSE CODE: GST 203 ASSIGNMENT Do a two page review of Chapter 7, “Political Parties in Nigeria,” in Salient issues in Government and Nigeria’s Politics. ANSWER There are as many definitions of political parties as the political thinkers. A political party is a group of officials or would-be officials who are linked with a sizable group of citizens into an organization; a chief object of this organization is to ensure that its officials attain power or maintain power. Political parties are an essential feature of politics in the modern age of mass participation. It is an important link between the government and the people. It was first developed in the nineteenth century in response to the appearance to elections involving large numbers of voters. Political parties have some characteristics which includes; to capture governmental powers through constitutional means, they have a broad principle of public policy adopted by its organization which is known as party ideology, every political party must be national-minded which means that it must take the interest of nation into consideration, there should be an organized body due to the fact that its strength comes from an effective organizational structure, they have party manifestoes which guide their conduct during and after election, they are guided by a party constitution which direct the conduct of party officials and members within and outside government. Political parties come in different types. The Elitist or Cadre parties. This is the political party that draws its membership from the highest echelon of social hierarchy in a country. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950.